On this day on 29th January

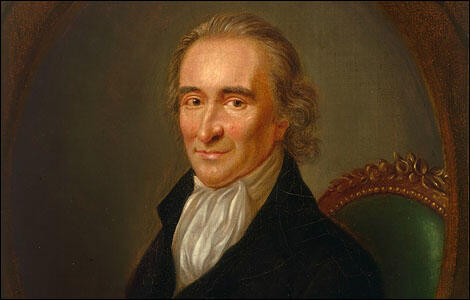

On this day 1737 philosopher Thomas Paine, the son of a Quaker corset maker, was born in Thetford in Norfolk. After being educated at the local grammar school Paine became an apprentice corset maker in Kent. This was followed by work as an exciseman in Lincolnshire and a school teacher in London.

In 1768 Paine moved to Lewes where he was employed as an excise officer. Paine became involved in local politics, serving on the town council and establishing a debating club in a local inn.

Thomas Paine upset his employers when he demanded a higher salary. Paine was dismissed and he responded by publishing a pamphlet The Case of the Officers of Excise. While in London Paine met Benjamin Franklin who encouraged him to emigrate to America.

Thomas Paine settled in Philadelphia where he became a journalist. Paine had several articles published in the Pennsylvania Magazine including one advocating the abolition of slavery. In 1776 he published Common Sense, a 47 page pamphlet that attacked the British Monarchy and advocated independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history. Paine argues in the pamphlet: "A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason."

Paine said of the Monarchy: "One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in kings, is, that nature disapproves it, otherwise, she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion... For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have the right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others forever, and tho' himself might deserve some decent degree of honours of his contemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them."

Paine believed that the monarchy led to wars: "In the early ages of the world, according to the scripture chronology, there were no kings; the consequence of which was there were no wars; it is the pride of kings which throws mankind into confusion... In England a king hath little more to do than to make war and give away places; which in plain terms, is to impoverish the nation and set it together by the ears. A pretty business indeed for a man to be allowed eight hundred thousand sterling a year for, and worshipped into the bargain! Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived."

During the war of American Independence Thomas Paine wrote articles and pamphlets on the superiority of republican democracy over monarchical government and served with Washington's armies. Paine also travelled to France in 1781 to raise money for the American cause.

Thomas Paine played no role in American government after independence and in 1787 he returned to Britain. Paine continued to write on political issues and in 1791 published his most influential work, The Rights of Man. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords.

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy. One person who read the book was the shoemaker, Thomas Hardy. In 1792 Hardy founded the London Corresponding Society. The aim of the organisation was to achieve the vote for all adult males.

In 1792 Thomas Paine became a French citizen and was elected to the National Convention. Paine upset French revolutionaries when he opposed the execution of Louis XVI. He was arrested and kept in prison under the threat of execution from 28th December 1793 and 4th November 1794. Paine was only released after the American minister, James Monroe, put pressure on the French government.

While in prison Thomas Paine worked on book on the subject of religion. Age of Reason was published soon after his release and caused a tremendous impact because it questioned the truth of Christianity. Paine criticised the Old Testament for being untrue and immoral and claimed that the Gospels contained inaccuracies and contradictions.

In 1802 Thomas Paine moved back to America but the Age of Reason had upset a large number of people and he discovered that he had lost the popularity he had enjoyed during the War of Independence. Unable to return to Britain, Paine remained in America until his death in New York on 8th June 1809. By the time he had died, over 1,500,000 copies of The Rights of Man had been sold in Europe.

On this day in 1832 Elizabeth Sharples became the "first Englishwoman to speak publicly on matters of politics and religion." Elizabeth was one of six children born to Ann and Richard Sharples, a manufacturer, in Bolton in 1803. The children received a good education, and Eliza attended boarding-school until she was about twenty.

Sharples held conservative views until she began reading The Republican in 1830. She wrote to its editor, Richard Carlile, and after "a rapid exchange of correspondence in which admiration turned to ardent love, she determined to share his work". Even before he had met Sharples in person, Carlile anticipated that she would become "my daughter, my sister, my friend, my companion, my wife, my sweetheart, my everything".

Richard Carlile published an article in his new newspaper, The Prompter, in support of agricultural labourers campaigning against wage cuts. Carlile's advice to the labourers was "to go on as you have done". (3) This was interpreted by the authorities as a seditious call to arms. Carlile was arrested and charged with seditious libel and appeared at the Old Bailey in January 1831. Carlile argued that "neither in deed, nor in word, nor in idea, did I ever encourage acts of arson or machine breaking".

The court was not convinced by his arguments and Carlile was found guilty of seditious libel and received a sentence of two years' imprisonment and a large fine which he refused to pay, thereby extending the sentence by a further six months. While in prison he continued to write articles for radical newspapers and pamphlets such as New View of Insanity (1831).

In January 1832 Elizabeth Sharples moved to London and visited Carlile in prison. Carlile had always campaigned for women's rights and he invited her to speak at his Blackfriars Rotunda. Several times a week speakers delivered "attacks on the superstitions of Christianity, which Carlile had now identified as the single most obdurate opposition to reform and liberation". The Rotunda became an important centre for working-class dissent and political reform. Speakers included William Cobbett, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Robert Owen, Daniel O'Connell, Robert Taylor and John Gale Jones. It is reported that at one meeting calling for parliamentary reform, drew a crowd of over 2,000 people.

Billed as "the first Englishwoman to speak publicly on matters of politics and religion" she gave her first talk on 29th January 1832. (7) The Times reported that she was "pretty, with a good figure and genteel manners" and dressed very well. (8) Sharples pointed out in her speech: "I will set before my sex the example of asserting an equality for them with their present lords and masters, and strive to teach all, yes, all, that the undue submission, which constitutes slavery, is honourable to none; while the mutual submission, which leads to mutual good, is to all alike dignified and honourable." (9) "Cast in the role of the Egyptian goddess Isis, she stood on the stage of the theatre, the floor strewn with whitethorn and laurel, and delivered lectures on mystical religion and women's rights."

Elizabeth Sharples was appointed as editor of a new radical weekly publication, Isis. She gave two lectures every Sunday (at sixpence for the pit and boxes, one shilling for the gallery), on Monday evenings (for half-price). She also gave a free lecture on Friday evenings to accommodate those unable to afford the entry charges.

Not everybody enjoyed her speeches. One man wrote to a national newspaper attacking the idea of a woman speaking in public: "Elizabeth Sharples is a female who exhibits herself in so unfeminine a manner... So utterly illiterate is the poor creature, that she cannot yet read what is set down for her with any degree of intelligibility... with her ignorance and unconquerable brogue... her lecturing is almost as ludicrous as it is painful to witness."

Richard Carlile supported Sharples in her campaign for women's rights: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man." Edward Royle adds that "this just about sums up the position of women in the radical movement". Even if a woman was emancipated she was expected to be the "proper companion of the public useful man".

Elizabeth Sharples argued in her newspaper articles that Christianity was the chief barrier to the dissemination of knowledge; by denying the people education, priests were denying man's liberty. She suggested that passive and non-resistance was seen as the "doctrine of priesthood".

Sharples was Carlile's greatest supporter while he was in prison. She used the Rotunda platform" to castigate the priesthood, expose religious superstition and denigrate established authority". She promised "sweet revenge" on those responsible for the "incarceration of Carlile". She visited him in prison and began a sexual relationship.

In 1832 Jane Carlile moved out of the family home and started a bookshop of her own. In April 1833 Elizabeth Sharples gave birth to a son, Richard Sharples. Carlile realized that he would have to acknowledge their relationship, and thereupon declared that he and Eliza were joined in a "moral marriage".

Elizabeth Sharples had the task of running the Blackfriars Rotunda while Carlile was in prison. In February 1832, she reported that £1,000 was needed to keep the venture open, to cover rent, taxes, lights and repairs. At the same time there had been a reduction in audiences. She admitted that she had lost the support of the radical community: "I believe I stand alone in the country, as a modern Eve, daring to pluck the fruit of the tree, and to give it to timid, sheepish man. I have received kindnesses and encouragements from a few ladies since my appearance in the metropolis, but how few."

In August 1833, Richard Carlile was released from prison.The couple lived on the corner of Bouverie Street and Fleet Street. Richard Sharples died of smallpox in October 1833. Another son, Julian Hibbert, was born in September 1834. In November 1835 they took a seven-year lease on a cottage in Enfield Highway, where shortly afterwards a daughter, Hypatia, was born. A fourth child, Theophila, followed a year later.

Elizabeth accompanied Richard Carlile on his lecture tours. His biographer, Philip W. Martin, pointed out: "Carlile's position was shifting radically. While it is clear that he never retreated to orthodoxy, his increasing use of Christian rhetoric and his own claims for himself as a Christian were a far cry from the radicalism of his early years. Carlile still propounded a sceptical, rational view of religion, but his allegorical readings had diminished to a single interpretation of Christianity in which he saw Christ and the resurrection as the rebirth of the soul of reason in humankind".

Richard Carlile was still capable of drawing large crowds (1500 people in Leeds in 1839, and 3000 people in Stroud in 1842), it was clear that most radicals rejected his religious views and were attracted to the political arguments of Chartism. He was also in poor health and he died of a bronchial infection on 10th February 1843. As he had dedicated his body to science it was taken to St Thomas's Hospital before his burial at Kensal Green Cemetery in London on 26th February.

At first the family was supported by Sophia Chichester, who arranged for Elizabeth Sharples to take charge of the sewing-room at the Alcott House in Ham, the home of a utopian spiritual community and progressive school. After a few months a small legacy from an aunt enabled her to set up on her own, letting apartments and maintaining her family by her needlework.

In 1849, Elizabeth Sharples set up a coffee and discussion room at 1 Warner Place, Hackney Road, in which to advocate radical freethought and women's rights. Charles Bradlaugh visited her and described her as "looking like a queen" but she was "no good at serving coffee".

Elizabeth Sharples died on 11th January 1852 at her home, 12 George Street, Hackney.

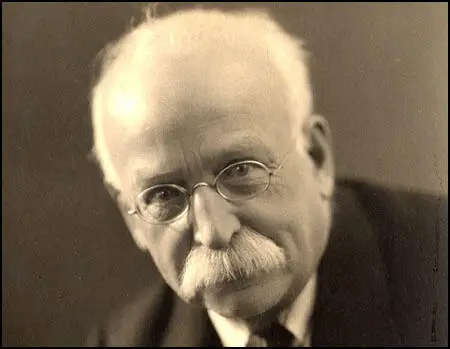

On this day 1850 Ebenezer Howard, the third child and only son of Ebenezer Howard, was born at 62 Fore Street in London on 29th January 1850. Four of the nine Howard children died in infancy. His father owned several shops in the city. According to one source: "Ebenezer senior was a healthy, energetic and hard-working man whose day's labour began at 3.00 a.m. and lasted into the evening. His vitality was matched by a strong constitution and it was his proud boast that he had never suffered from a headache in over seventy years."

Howard was educated at private boarding-schools, first at Sudbury, then at Cheshunt and finally at Ipswich. He had a moderate academic career and was much more interested in his hobbies that included drawing, swimming, cricket, stamp collecting and photography. His reading appears to have been limited to the Boys' Own Magazine.

In 1865 Ebenezer Howard left school and found work in Greaves and Son, stockbrokers, of Warnford Court, London. His duties were mainly to copy out letters into a book using a quill pen. This was followed by employment as a junior clerk. During this period he taught himself Pitman's shorthand. This gave him the skills needed to work in solicitors' offices, first with E. Kimber of Winchester Buildings, and then Pawle, Livesey and Fearon whose offices were near Temple Bar. This was followed by becoming the private secretary to the preacher, Joseph Parker.

At the age of twenty-one Ebenezer Howard decided to emigrate to the United States. After a failed attempt to become a farmer in Nebraska, he became a stenographer in Chicago. Howard also became interested in political issues. He read the works of Tom Paine and began calling himself a "freethinker". Howard later commented: "I am, indeed, as my friends know, a man of some faith; but I am also - perhaps the combination is somewhat rare - a terrible sceptic." Alonzo Griffin, a Quaker, introduced him to the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman and James Russell Lowell.

Ebenezer Howard also became concerned with the subject of social reform. He was especially impressed with the experiments being carried out by Frederick Law Olmsted. He had designed the town of Riverside. As John Moss-Eccardt has pointed out: "Planned by Frederick Law Olmsted, this town had 700 of its 16,000 acres devoted to green roads, borders, parks and other features which produced a pleasing blend of town and country. Within this environment the Riverside citizen could pursue rural activities in congenial surroundings which combined the benefits of both worlds."

In 1876 Howard returned to London where he found work as a stenographer working in the House of Commons. Eventually he established his own business in Carey Street and in 1879 he married Elizabeth Ann Bills of Nuneaton. Over the next seven years she had four children, Cecil, Edith, Kathleen and Margery. A fifth died in infancy. According to the author of Ebenezer Howard (1973): "Their home life was very happy and Mrs Howard managed the family finances expertly... The couple were never irritable or annoyed with the children and the shortage of money seems to have made no difference at all to their enjoyment of life."

Howard became very interested in social reform. In 1879 Howard joined the Zetetical Society, a philosophical and sociological debating group, which met weekly in the rooms of the Women's Protective & Provident League in Long Acre and got to know fellow members, George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb. He was also influenced by the work of William Blake, Thomas Spence, Henry George, William Morris, John Ruskin and Peter Kropotkin. He was especially impressed with George's Progress and Poverty and Kropotkin's Fields, Factories and Workshops.

In 1889 Howard read Looking Backward, a novel by Edward Bellemy. Set in Boston, the book's hero, Julian West, falls into a hypnotic sleep and wakes in the year 2000, to find he is living in a socialist utopia where people co-operate rather than compete. Edward W. Younkins has argued: "This novel of social reform was published in 1888, a time when Americans were frightened by working class violence and disgusted by the conspicuous consumption of the privileged minority. Bitter strikes occurred as labor unions were just beginning to appear and large trusts dominated the nation’s economy. The author thus employs projections of the year 2000 to put 1887 society under scrutiny. Bellamy presents Americans with portraits of a desirable future and of their present day. He defines his perfect society as the antithesis of his current society. Looking Backward embodies his suspicion of free markets and his admiration for centralized planning and deliberate design."

Howard later commented: "This I read at a sitting, not at all critically, and was fairly carried away by the eloquence and evidently strong convictions of the author. This book graphically pictured the whole American nation organised on co-operative principles-this mighty change coming about with marvellous celerity-the necessary mental and ethical changes having previously occurred with equal rapidity. The next morning as I went up to the City from Stamford Hill I realised, as never before, the splendid possibilities of a new civilisation based on service to the community and not on self-interest, at present the dominant motive. Then I determined to take such part as I could, however small it might be, in helping to bring a new civilisation into being."

As a first step he persuaded William Reeves, a radical Fleet Street publisher, to bring out an English edition, but only by offering to take the first 100 copies. Howard also began thinking of what his utopia would look like. As Mervyn Miller, the author of English Garden Cities: An Introduction (2010) has pointed out: "Howard's objective was to find a remedy for overcrowded and unhealthy conditions in the fast-growing industrial cities, and the accompanying rural depopulation and agricultural depression. He believed access to the countryside to be necessary for the complete physical and social development of humankind. It was no longer acceptable for urban development to be left to the minimally regulated private enterprise of landowners and industrialists. In taking evidence for royal commissions, Howard had been impressed by the unanimity of opinion of labour and capital over the failure of the city to provide decent housing and working conditions. Howard's solution was to provide a new form of settlement as a vehicle for radical social and environmental reform. He proposed the development of new towns, not for individual or corporate profit, but for the benefit of the whole community. These, the garden cities, were to be both residential and industrial, well planned, of limited size and population, and surrounded by a permanent rural belt, integrating the best aspects of town and country. Each garden city was to be self-contained, and built on land purchased by trustees, and used as an asset, against which the cost of development would be raised. The value of the land would increase, and periodic revaluation of the plots leased to individuals would reap the benefit for the community, with dividends to shareholders in the enterprise limited to 5 per cent."

Over the next ten years Howard worked on producing the blueprint of his "path to peaceful reform". John Moss-Eccardt has argued: "The work was done at odd times gleaned from the hours spent in the very necessary business of making a living. He wrote on the dining table, often during meals, at Kyverdale Road, Stoke Newington, and copies were typed by a cousin because he couldn't afford to pay a professional typist. As the work grew he circulated the typescript to friends both in local government and in the church. In spite of great interest in his ideas from various sections of his circle, the book remained in typescript form as no one would risk its publication; but fate seemed to take a hand when help came from a friend known to Howard and his wife through a common interest in religion."

George Dickman, a friend of the family, gave Howard £50 so that he could get the finished manuscript published. Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform was published in October 1898. Howard later admitted, "my friends and supporters never regarded this book, any more than I did, as more than a sketch or outline of what we hoped to accomplish". The Times praised his ideas but dismissed them as impractical: "The only difficulty is to create such a City, but that is a small matter to Utopians".

Ebenezer Howard argues in Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform that he hopes to build what he calls a Garden City: "The objects of this land purchase may be stated in various ways, but it is sufficient here to say that some of the chief objects are these: To find for our industrial population work at wages of higher purchasing power, and to secure healthier surroundings and more regular employment. To enterprising manufacturers, co-operative societies, architects, engineers, builders, and mechanicians of all kinds, as well as to many engaged in various professions, it is intended to offer a means of securing new and better employment for their capital and talents, while to the agriculturists at present on the estate as well as to those who may migrate thither, it is designed to open a new market for their produce close to their doors. Its object is, in short, to raise the standard of health and comfort of all true workers of whatever grade - the means by which these objects are to be achieved being a healthy, natural, and economic combination of town and country life, and this on land owned by the municipality."

Howard then went on to claim that the "Garden City, which is to be built near the centre of the 6,000 acres, covers an area of 1,000 acres, or a sixth part of the 6,000 acres, and might be of circular form, 1,240 yards (or nearly three-quarters of a mile) from centre to circumference.... Six magnificent boulevards-each 120 feet wide-traverse the city from centre to circumference, dividing it into six equal parts or wards. In the centre is a circular space containing about five and a half acres, laid out as a beautiful and well-watered garden; and, surrounding this garden, each standing in its own ample grounds, are the larger public buildings - town hall, principal concert and lecture hall, theatre, library, museum, picture-gallery, and hospital."

George Dickman, a friend of the family, gave Howard £50 so that he could get the finished manuscript published. Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform was published in October 1898. Howard later admitted, "my friends and supporters never regarded this book, any more than I did, as more than a sketch or outline of what we hoped to accomplish". The Times praised his ideas but dismissed them as impractical: "The only difficulty is to create such a City, but that is a small matter to Utopians".

Ebenezer Howard's friend, George Bernard Shaw, described him as an amazing man who deserved a knighthood and supported his efforts. Walter Crane was another socialist who fully supported his proposals. However, other members of the Fabian Society were much more critical. They disliked the way that Howard criticised socialist views on the role of the state in town planning. Howard admitted that he approved of some of the values of the left: "Communism is a most excellent principle, and all of us are Communists in some degree, even those who would shudder at being told so. For we all believe in communistic roads, communistic parks, and communistic libraries. But though Communism is an excellent principle. Individualism is no less excellent. A great orchestra which enraptures us with its delightful music is composed of men and women who are accustomed not only to play together, but to practise separately, and to delight themselves and their friends by their own, it may be comparatively, feeble efforts. Nay, more: isolated and individual thought and action are as essential, if the best results of combination are to be secured, as combination and co-operation are essential, if the best results of isolated effort are to be gained. It is by isolated thought that new combinations are worked out; it is through the lessons learned in associated effort that the best individual work is accomplished; and that society will prove the most healthy and vigorous where the freest and fullest opportunities are afforded alike for individual and for combined effort."

Ebenezer Howard went on to argue: "Men love combined effort, but they love individual effort, too, and they will not be content with such few opportunities for personal effort as they would be allowed to make in a rigid socialistic community. Men do not object to being organized under competent leadership, but some also want to be leaders, and to have a share in the work of organizing; they like to lead as well as to be led. Besides, one can easily imagine men filled with a desire to serve the community in some way which the community as a whole did not at the moment appreciate the advantage of, and who would be precluded by the very constitution of the socialistic state from carrying their proposals into effect."

Socialists tended to want to reform existing towns and cities. The Fabian News commented: "His plans would have been in time if they had been submitted to the Romans when they conquered Britain. They set about laying out cities, and our forefathers have dwelt in them to this day. Now Mr Howard proposes to pull them down and substitute garden cities, each duly built according to pretty coloured plans, nicely designed with a ruler and compass. The author has read many learned and interesting writers, and the extracts he makes from their books are like plums in the unpalatable dough of his Utopian scheming. We have got to make the best of our existing cities, and proposals for building new ones are about as useful as would be arrangements for protection against visits from Mr Wells's Martians."

On 10th June 1899, Ebenezer Howard and his friends established the Garden City Association. The Association organised lectures on "garden cities as a solution of the housing problem" which were addressed "to educational, social, political, co-operative, municipal, religious and temperance societies and institutions". Important members included Edward Grey, William Lever, Edward Cadbury, Ralph Neville, Thomas Howell Idris and Aneurin Williams.

In 1900 the Garden City Limited was established with share capital of £50,000. The following year a conference was held at Bournville which three hundred delegates attended. Over a thousand attended the national conference at Port Sunlight in June 1902. Howard's book was now reissued as Garden Cities of Tomorrow. By 1903 the Garden City Association had over 2,500 members. The Garden City Pioneer Company was constituted, with Howard as managing director, to find a suitable site for the first garden city. In 1903 Howard purchased 3,818 acres in Letchworth for £155,587.

Ebenezer Howard employed Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker as the architects responsible for building Letchworth Garden City. Both men were greatly interested in social reform and had been greatly influenced by John Ruskin and William Morris. They had previously been employed by Joseph Rowntree to establish an estate for his workers in New Earswick. As John Moss-Eccardt pointed out: "Both young men wanted to express their convictions, which were greatly influenced by Ruskin and Morris, in visual architecture... This was an important part of the social reform movement, more than a mere alleviation of poor housing and environmental conditions in industrial towns. It ranked as a forerunner of garden cities in that it paid attention deliberately to creating an environment which promoted health and happiness in its inhabitants."

Unwin explained: "The successful setting out of such a work as a new city will only be accomplished by the frank acceptance of the natural conditions of the site; and, humbly bowing to these, by the fearless following out of some definite and orderly design based on them ... such natural features should be taken as the keynote of the composition; but beyond this there must be no meandering in a false imitation of so-called natural lines."

Parker held strong views on creating a beautiful environment. He believed that the destruction of a single tree should be avoided, unless absolutely necessary. It was decided that it was important to make full "use of the undulating nature of the terrain to provide vistas and prospects. By grouping numbers of houses together it was possible to have large gaps between the groups, thus providing views of gardens, countryside or buildings beyond."

Andrew Saint has argued: "The concept of the self-sufficient garden city promoted by Howard in Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1898–1902) having been entirely diagrammatic, Unwin was in effect asked to endow Letchworth with an image and identity. This raised issues of industrial and civic planning, phasing, and investment on a scale that no British architect had hitherto faced. The plan was revised in 1905–6, when work at Letchworth commenced. The housing areas got the earliest attention, Unwin tackling road layout, grouping, plot size, style, and supervision with originality and a remarkable perception of the complex issues. But Letchworth's civic centre, which was allotted an axial approach perhaps derived from Wren's plan for rebuilding London, grew too slowly for the ideas of Parker and Unwin to be carried through, and remains a grave disappointment. Despite Unwin's critical role at Letchworth, where he lived between 1904 and 1906, he never identified wholly with Howard's obsession with autonomous garden cities on virgin sites detached from metropolitan influence, and indeed left further work at Letchworth to Parker after 1914."

Ebenezer Howard died in the late autumn of 1904. Howard moved to a house in Norton Way South in Letchworth Garden City. On 25th March 1907 he remarried; his second wife, Edith Hayward, a 42-year-old spinster. During these years Letchworth continued to grow. Howard did what he could to develop a community spirit. Activities ranged from Arbor Days (a holiday in which individuals and groups are encouraged to plant and care for trees), May Day festivities, amateur dramatics and poetry readings.

The aftermath of the First World War brought government involvement with the provision of working-class housing, through grants made to local authorities under the 1919 Housing Act. However, Howard was disappointed by the lack of commitment to the building of new self-contained communities by state or private enterprise and decided to look for a place to build a second Garden City. Eventually, Howard purchased 1,458 acres in Hertfordshire.

On 29th April 1920 a company, Welwyn Garden City Limited, was formed to plan and build the garden city. Louis de Soissons was appointed as architect and town planner and the first house was occupied just before Christmas 1920. To support it in its early years, Howard moved to 5 Guessens Road on the estate. In twelve years Welwyn Garden became a flourishing town of nearly 10,000 residents.

According to his biographer, Mervyn Miller: "Howard remained a poor man all his life, receiving little monetary return from his directorships at Letchworth and Welwyn. He was devoid of personal ambition, but had a remarkable gift of inspiring other people. Being absolutely convinced of the rightness of his ideas, he was driven by an ardent enthusiasm. Neither a professional town planner nor a financier, he convinced town planners and financiers of the practical soundness of his ideas, but readily accepted their expertise in carrying his concepts into practice... Public recognition came late in life: he was appointed OBE in 1924 and knighted in 1927." George Bernard Shaw described him as "one of those heroic simpletons who do big things whilst our prominent worldlings are explaining why they are Utopian and impossible. And of course it is they who will make money out of his work".

Ebenezer Howard died on 1st May, 1928.

On this day in 1858 journalist Charles Repington was born at 15 Chesham Street, London. His father, Henry Wyndham Repington, was Conservative MP for Wilton (1852-1855).

Repington was educated at Eton College (1871-76) and Sandhurst Military College (1876-78). He joined the Rifle Brigade and after active service in Afghanistan, he entered the Camberley Staff College (1887-89). Fellow students included Herbert Plumer and Horace Smith-Dorrien.

He took part in the Boer War and his biographer, A. J. A. Morris, has argued: "When invalided home from the South African campaign he had reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel, had been mentioned in dispatches four times, and created CMG. Bold, tenacious, able, ambitious, and hard-working, he had proved himself a fine regimental, and an outstanding staff officer. But his considerable virtues were complemented by not inconsiderable faults. He was extravagant, impetuous, and sometimes cavalier in his attitude to authority and routine. He never suffered fools gladly, whatever their rank."

In 1900 Repington was posted to Egypt where he became involved with Mary North Garstin (1868–1953) the wife of Sir William Edmund Garstin, a senior official in the Egyptian ministry of public works. The military authorities warned Repington about his behaviour and he gave his written promise, "upon his honour as a soldier and a gentleman" to stop seeing the woman. However, the relationship continued and when Garstin named Repington in divorce proceedings, he was forced to resign from the army. Repington blamed Henry Wilson, his commanding officer, for his dismissal.

Repington turned to journalism and his first regular contributions were to The Westminster Gazette. He was also military correspondent of the Morning Post (1902-1904) before joining The Times in 1904. His accounts of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–5 earned him international recognition as an outstanding military commentator.

Charles Repington had strong views on defence matters. A. J. A. Morris has argued: "International tensions forced changes in British foreign policy that in turn posed complex defence problems. Repington offered solutions that his civilian readers could comprehend. He advocated a general staff, and, believing in the co-ordination of military and naval planning and closer imperial ties, was an enthusiastic supporter of the infant committee of imperial defence. He opposed the dominant ‘blue water’ strategists, who claimed the navy alone was sufficient to secure Britain against invasion." Repington also warned of a possible German invasion and was a strong supporter of an alliance with France and in 1905 he was awarded the Légion d'honneur for working as their intermediary.

Repington disliked nearly all politicians. He told Leo Maxse, the editor of The National Review, that they were "Tadpoles and Tapers shivering for their shekel… rabble seeking office and rewards." Most ministers were "ignorant… uncaring… they know nothing of the Army". The only senior politician he had time for was Richard Haldane who he called "the best Secretary of State we have had at the War Office so far as brain and ability are concerned" and generally supported his military reforms.

On the outbreak of the First World War Repington remained in London and relied on his contacts in the British Army and the War Office for his information. Through his friendship with the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, Sir John French, Repington was invited to visit the Western Front in November 1914, whereas most war correspondents were banned from France.

On a visit to France during the offensive at Artois, Repington was shown confidential information about the British Army being short of artillery shells. When his article about the shell shortage appeared in The Daily Mail, its owner, Lord Northcliffe, called for Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, to be sacked. Repington now had growing influence over military policy and one politician described him as "the twenty-third member of the Cabinet". The discussion that followed Repington's article resulted in David Lloyd George being appointed Minister of Munitions. However, Lord Kitchener got his revenge on Repington by getting him banned from the front-line and he was not allowed to return until March, 1916.

Repington was a strong advocate of war by attrition and supported General William Robertson and his leading advisor, Frederick Maurice, that the war would be won by the allies concentrating their forces on the Western Front. The prime-minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, did not challenge this approach to the war. However, he lost office after the failure of the Somme Offensive. His replacement, David Lloyd George, disagreed with this strategy and at various stages advocated a campaign on the Italian front and sought to divert military resources to the Turkish theatre. Repington was highly critical of what he described as "side-shows" and accused Lloyd George of being an "amateur strategist" who starved the army of the men and munitions it required. Some of Repington's articles were censored by his editor, Geoffrey Dawson, and in January 1918, he resigned from The Times and joined the Morning Post.

According to the historian, Michael Kettle, Repington became involved in a plot to overthrow David Lloyd George. Others involved in the conspiracy included General William Robertson, Chief of Staff and the prime ministers main political adviser, Maurice Hankey, the secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) and General Frederick Maurice, director of military operations at the War Office. Kettle argues that: "What Maurice had in mind was a small War Cabinet, dominated by Robertson, assisted by a brilliant British Ludendorff, and with a subservient Prime Minister. It is unclear who Maurice had in mind for this Ludendorff figure; but it is very clear that the intention was to get rid of Lloyd George - and quickly."

On 24th January, 1918, Repington wrote an article where he described what he called "the procrastination and cowardice of the Cabinet". Later that day Repington heard on good authority that Lloyd George had strongly urged the War Cabinet to imprison both him and his editor, Howell Arthur Gwynne. That evening Repington was invited to have dinner with Lord Chief Justice Charles Darling, where he received a polite judicial rebuke.

General William Robertson disagreed with Lloyd George's proposal to create an executive war board, chaired by Ferdinand Foch, with broad powers over allied reserves. Robertson expressed his opposition to General Herbert Plumer in a letter on 4th February, 1918: "It is impossible to have Chiefs of the General Staffs dealing with operations in all respects except reserves and to have people with no other responsibilities dealing with reserves and nothing else. In fact the decision is unsound, and neither do I see how it is to be worked either legally or constitutionally."

On 11th February, Repington, revealed in the Morning Post details of the coming offensive on the Western Front. Lloyd George later recorded: "The conspirators decided to publish the war plans of the Allies for the coming German offensive. Repington's betrayal might and ought to have decided the war." Repington and his editor, Howell Arthur Gwynne, were fined £100 each, plus costs, for a breach of Defence of the Realm regulations when he disclosed secret information in the newspaper.

General William Robertson wrote to Repington suggesting that he had been the one who had leaked him the information: "Like yourself, I did what I thought was best in the general interests of the country. I feel that your sacrifice has been great and that you have a difficult time in front of you. But the great thing is to keep on a straight course". General Frederick Maurice also sent a letter to Repington: "I have the greatest admiration for your courage and determination and am quite clear that you have been the victim of political persecution such as I did not think was possible in England."

Robertson put up a fight in the war cabinet against the proposed executive war board, but when it was clear that Lloyd George was unwilling to back down, he resigned his post. He was now replaced with General Henry Wilson. General Douglas Haig rejected the idea that Robertson should become one of his commanders in France and he was given the eastern command instead.

After the war Repington worked for the Daily Telegraph. His editor, Edward Lawson-Levy, commented: "He wrote at a time in international affairs when his special knowledge and talent were particularly valuable. Though his critics chose to regard him as a somewhat extinct volcano... however he retained the distinction which characterized all that he did."

Repington also wrote several books on the war including The First World War (1920) and After the War (1922). In these books Repington divulged private conversations and correspondence. Although the books sold well, Repington was shunned by former friends who felt he had betrayed them. His biographer, A. J. A. Morris has pointed out: "Though they remain an important historical source, at the time his public recollection of private gossip further damaged his already precarious social position. Repington's wife had refused to divorce him. Nevertheless Mary Garstin, through all their vicissitudes, supported Repington: she took his name, lived with him as his wife, bore him a daughter, and forgave him his not infrequent indiscretions."

Charles Repington died at his home, Pembroke Lodge, Hove on 25th May, 1925. He was buried at St Barnabas's Church on 29 May.

On this day in 1872 William Rothenstein, the fifth of the six children of Moritz Rothenstein (1836–1915) and his wife, Bertha Dux (1844–1912), was born at 4 Spring Bank, Bradford. His father, a businessman, had arrived from Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, in 1859.

Rothenstein was educated at Bradford Grammar School where he developed a strong interest in art. In 1888 he went to the Slade School of Fine Art where he came under the influence of Alphonse Legros. The following year he attended the Académie Julian in Paris. During this period he met Roger Fry, Oscar Wilde, Walter Sickert, James Whistler, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas and Paul Verlaine. His biographer, Mary Lago, has pointed out: "He became known as a person with a gift for friendship and as a precocious talent." Max Beerbohm commented: "He was a wit. He was brimful of ideas. He knew Whistler. He knew Edmond de Goncourt. He knew everyone in Paris. He knew them all by heart. He was Paris in Oxford." As a result of his contacts, Rothenstein was commissioned to produce Oxford Characters (1896) and English Portraits (1898).

On 11th June 1899, Rothenstein married Alice Mary Knewstub (1869–1955), who had appeared on the stage as Alice Kingsley. They had four children, John, William, Rachel and Betty. He rented a studio in Spitalfields and began his eight Synagogue Paintings. These paintings dealt with Jewish religious life.

Rothenstein took a keen interest in the work of young artists. This included Augustus John who wrote in his autobiography, Chiaroscuro: "Encouraged by Will Rothenstein, I held my first show at the newly established Carfax Gallery, Ryder Street, St. James's... My little show was a success. I made thirty pounds. With this sum in my pocket there was nothing to prevent me joining Will Rothenstein, Orpen and Charles Conder in France. Rothenstein had found a good spot not far from Étretat on the Normandy coast."

Rothenstein, Augustus John and Charles Conder went to Paris to visit Oscar Wilde. John later recalled: "I had heard a lot about Oscar, of course, and on meeting him was not in the least disappointed, except in one respect: prison discipline had left one, and apparently only one, mark on him, and that not irremediable: his hair was cut short... We assembled first at the Cafe de la Regence.... The Monarch of the dinner-table seemed none the worse for his recent misadventures and showed no sign of bitterness, resentment or remorse. Surrounded by devout adherents, he repaid their hospitality by an easy flow of practised wit and wisdom, by which he seemed to amuse himself as much as anybody. The obligation of continual applause I, for one, found irksome. Never, I thought, had the face of praise looked more foolish."

Augustus John was the subject of his painting, The Dolls House (1900). He later wrote: "It was at Vattetot that William Rothenstein painted The Doll’s House for which Alice Rothenstein and I posed. This is a regular problem picture. I am portrayed standing at the foot of a staircase upon which Alice has un accountably seated herself. I appear to be ready for the road, for I am carrying a mackintosh on my arm and am shod and hatted. But Alice seems to hesitate. Can she have changed her mind at the last moment? But what could have been her intention? Perhaps the weather had changed for the worse and made a promenade inadvisable: but we shall never know. The picture will remain a perpetual enigma, to disturb, fascinate or repel".

In 1907 Rothenstein gave important support to Jacob Epstein. Rothenstein also took a keen interest in the career of Mark Gertler. After seeing the work of the sixteen-year-old East Ender in 1908 he wrote to his father: "It is never easy to prophesy regarding the future of an artist but I do sincerely believe that your son has gifts of a high order, and that if he will cultivate them with love and care, that you will one day have reason to be proud of him. I believe that a good artist is a very noble man, and it is worth while giving up many things which men consider very important, for others which we think still more so. From the little I could see of the character of your son, I have faith in him and I hope and believe he will make the best possible use of the opportunities I gather you are going to be generous enough to give him." Rothenstein managed to secure a place at the Slade School of Fine Art and arranged for his fees to be paid by the Jewish Educational Aid Society.

Rothenstein took a keen interest in Mughal Painting and in 1910 established an India Society to educate the British public about Indian arts. Later that year he went to India with the painter Christiana Herringham, who had been involved in a project copying the rapidly deteriorating Buddhist wall-paintings in the Ajanta Caves. While in Calcutta (Kolcata) he met the poet Rabindranath Tagore. It has been claimed by Mary Lago that: "The influence of Indian art led to changes in Rothenstein's own painting: enamoured of the mass and solidity of Indian architecture, his own Indian scenes became heavier in style where formerly they had been light and delicate."

While he was in India, Roger Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy were in Paris visiting "Parisian dealers and private collectors, arranging an assortment of paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries" in Mayfair. This included a selection of paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, André Derain and Vincent Van Gogh. As the author of Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Although some of these paintings were already twenty or even thirty years old - and four of the five major artists represented were dead - they were new to most Londoners." This exhibition had a marked impression on the work of Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Spencer Gore.

Henry Tonks, one of Britain's leading artists and the most important teacher at the Slade Art School, told his students that although he could not prevent them visiting the Grafton Galleries, he could tell them "how very much better pleased he would be if we did not risk contamination but stayed away". The critic for The Pall Mall Gazette described the paintings as the "output of a lunatic asylum". Robert Ross of The Morning Post agreed claiming the "emotions of these painters... are of no interest except to the student of pathology and the specialist in abnormality". These comments were especially hurtful to Fry as his wife had recently been committed to an institution suffering from schizophrenia. Paul Nash recalled that he saw Claude Phillips, the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, on leaving the exhibition, "threw down his catalogue upon the threshold of the Grafton Galleries and stamped on it."

William Rothenstein also disliked Fry's post-impressionist exhibition. He wrote in his autobiography, Men and Memories (1932) that he feared that the excessive publicity that the exhibition received, would seduce younger artists from "more personal, more scrupulous work". Rothenstein was in great demand as a lecturer and he used this position to deal with "philosophical questions concerning the meaning of art, the function of art schools and museums, the artist's role in an industrial culture, and, in the decline of personal patronage, the importance of generating municipal support for artists and craftsmen."

On the outbreak of First World War in 1914 the Rothenstein family suffered from strong anti-German feeling in Britain. The three brothers decided to change the family name to Rutherston. Charles and Albert went through with the change but at the last minute William decided that it "meant too great a sacrifice of continuity and identity" and remained as Rothenstein.

Only two photographers, both army officers, were allowed to take pictures of the Western Front. The penalty for anyone else caught taking a photograph of the war was the firing squad. Charles Masterman, head of the War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), was aware that the right sort of pictures would help the war effort. In May 1916 Masterman recruited the artist, Muirhead Bone. He was sent to France and by October had produced 150 drawings of the war. When Bone returned to England he was replaced by his brother-in-law, Francis Dodd, who had been working for the Manchester Guardian.

Rothenstein offered his services to the WPB but because of his German connections he was initially turned down. However, in December 1917 he was allowed to join other artists abroad including Eric Kennington, William Orpen, Paul Nash, John Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, John Sargent, Augustus John, Henry Lamb, Colin Gill, William Roberts, Wyndham Lewis, Stanley Spencer, Philip Wilson Steer, George Clausen, Bernard Meninsky, Charles Pears, Sydney Carline, David Bomberg, Austin Osman Spare, Gilbert Ledward and Charles Jagger.

Soon after he arrived on the Somme front he was arrested as a spy. He stayed with the British Fifth Army in 1918 and during the German Spring Offensive, served as a unofficial medical orderly. He returned to England in March and his pictures were exhibited in May, 1918. Pictures by Rothenstein included The Ypres Salient and Talbot House, Ypres.

After the war Rothenstein returned to London. In 1919 Herbert Fisher, president of the Board of Education, appointed Rothenstein to write a report on the Royal College of Art. Rothenstein's report found that "the separation between training and employment for artists on the one hand, and for designers and industrial craftsmen on the other, was imbalanced, and advised that art training should encourage experimentation and flexibility for both." Fisher then appointed Rothenstein, as principal of the college.

Rothenstein continued to promote the careers of experimental artists such as Henry Moore. He neglected his own work and as Mary Lago has pointed out: "His greater intensity and earnestness were evident in his habitual dissatisfaction with his own work, his fears about loss of facility in draughtsmanship, and his concern over the spiritual content both in his own work and that of his colleagues." He also wrote two volumes of autobiograpy, Men and Memories (1932) and Since Fifty (1939).

Although sixty-six when the Second World War started, Rothenstein, who was suffering from heart problems, became an artist with the Royal Air Force. Unable to go abroad he made portrait drawings of airmen at RAF bases in England.

William Rothenstein died at his home on 14th February 1945 and was buried at St Bartholomew's Church, Oakridge, Gloucestershire.

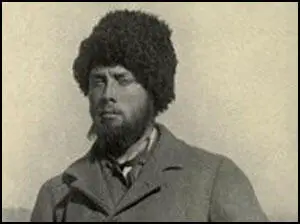

On this day in 1885 journalist Morgan Philips Price was born in Taynton, Gloucestershire. The son of William Edwin Price, MP for Tewkesbury, he was educated at Harrow. He later recalled: "When I was fourteen I went to Harrow. My father had been to Eton, but my Trevelyan uncle and cousins had all been to Harrow, so my mother found it easier to get my name down for a house. I was very glad she made that choice. I owe much to Harrow and in all my later life have looked back on the old School with veneration, love and respect."

Price then went to Trinity College. In 1906 he inherited a 2000-acre estate. A member of the Liberal Party, Price became prospective party candidate for Gloucester in 1911. He was on the left of the party and soon after his selection he argued: "What in general we have to realize is that the State has to compromise between private and public interests. Private interests, enterprise and initiative must be allowed free play up to a point, but the great Liberal principle is that wherever private interests can be shown to be in antagonism to public interests, then the public interests must prevail. One of the best ways of preventing abuse of private monopoly and privilege is by the free exercise of economic laws or, in other words, by free trade. I look also with great sympathy on the movement of organized labour, because I maintain that if it is properly guided it can be of the greatest progressive force in this country and I am sure that in time the Labour movement will become an international movement and the only great force that will secure international peace."

Price was against Britain's participation in the First World War. In his memoirs he recalled discussing the issue with Charles Trevelyan, E. D. Morel, Bertrand Russell, Arthur Ponsonby and Ramsay MacDonald: "All these doubts about the circumstances under which we had become involved in the First World War were welling up in my mind in the latter part of 1914. In London, I went to see my cousin, Sir Charles Trevelyan, who held the same views as I did, and together we went to see Bertrand Russell, E. D. Morel, Arthur Ponsonby, Lowes Dickinson and Ramsay Macdonald, who had made a very courageous speech in the House on the declaration of War." The men decided to form the Union of Democratic Control, the most important of all the anti-war organizations in Britain. Price's major contribution was the publication of The Diplomatic History of the War (1914).

Price spoke Russian and he was recruited by C.P. Scott to report the war on the Eastern Front for the Manchester Guardian. "He (C. P. Scott) asked me to lunch at his house in Fallowfield and there we arranged something that was to become one of the turning points of my life. It turned out that Scott had been thinking just as I had. He scouted the whole idea that Tsarist Russia was going to change as the result of being allied to us and France; rather he feared the reverse might happen. He wanted someone to go to Russia for the Manchester Guardian and keep him informed about what was happening there. He might not be able to publish everything that was sent for reasons connected with the War, but at least he wanted to be informed."

Price was sent to Petrograd and reported on the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II. On 8th July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky became the new leader of the Provisional Government. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. However, Kerensky, like his predecessor, George Lvov, was unwilling to end the war. In fact, soon after taking office, he announced a new summer offensive.

The Bolsheviks grew in strength and Price watched their leaders, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, very closely during this period. "Lenin struck me as being a man who, in spite of the revolutionary jargon that he used, was aware of the obstacles facing him and his party. There was no doubt that Lenin was the driving force behind the Bolshevik Party... He was the brains and the planner, but not the orator or the rabble-rouser. That function fell to Trotsky. I watched the latter, several times that evening, rouse the Congress delegates, who were becoming listless, probably through long hours of excitement and waiting. He was always the man who could say the right thing at the right moment. I could see that there was beginning now that fruitful partnership between him and Lenin that did so much to carry the Revolution through the critical periods that were coming."

Price explained in the Manchester Guardian on 19th November, 1917, why the government of Alexander Kerensky fell: "The Government of Kerensky fell before the Bolshevik insurgents because it had no supporters in the country. The bourgeois parties and the generals and the staff disliked it because it would not establish a military dictatorship. The Revolutionary Democracy lost faith in it because after eight months it had neither given land to the peasants nor established State control of industries, nor advanced the cause of the Russian peace programme. Instead it brought off the July advance without any guarantee that the Allies had agreed to reconsider war aims. The Bolsheviks thus acquired great support all over the country. In my journey in the provinces in September and October I noticed that every local Soviet had been captured by them."

Price was initially sympathetic to the leaders of the Russian Revolution. However, he disapproved of the Constituent Assemby being closed down and the banning political parties such as the Cadets, Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries. Price reported on those Bolsheviks who disapproved of these tactics. This included interviewing Rosa Luxemburg in while in prison in Berlin. He later reported: "She asked me if the Soviets were working entirely satisfactorily. I replied, with some surprise, that of course they were. She looked at me for a moment, and I remember an indication of slight doubt on her face, but she said nothing more. Then we talked about something else and soon after that I left. Though at the moment when she asked me that question I was a little taken aback, I soon forgot about it. I was still so dedicated to the Russian Revolution, which I had been defending against the Western Allies' war of intervention, that I had had no time for anything else."

On his return to England, Price published My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution (1921). In the book he criticised Lenin's Bolshevik government and instead supported the views put forward by Rosa Luxemburg: "She did not like the Russian Communist Party monopolizing all power in the Soviets and expelling anyone who disagreed with it. She feared that Lenin's policy had brought about, not the dictatorship of the working classes over the middle classes, which she approved of but the dictatorship of the Communist Party over the working classes. The dictatorship of a class - yes, she said, but not the dictatorship of a party over a class."

Price worked for the Daily Herald in Germany (1919-23) and after joining the Labour Party, was its unsuccessful candidate for Gloucester in three successive elections (1922, 1923 and 1924). He was elected to represent Whitehaven in the 1929 General Election and was appointed by Ramsay MacDonald as Private Secretary to Charles Trevelyan, president of the Board of Education.

In March 1931 MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. The committee included two members that had been nominated from the three main political parties. At the same time, John Maynard Keynes, the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council, published his report on the causes and remedies for the depression. This included an increase in public spending and by curtailing British investment overseas.

Philip Snowden rejected these ideas and this was followed by the resignation of Price's uncle, Charles Trevelyan, the Minister of Education. "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative."

When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it forecast a huge budget deficit of £120 million and recommended that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. The two Labour Party nominees on the committee, Arthur Pugh and Charles Latham, refused to endorse the report. As David W. Howell has pointed out: "A committee majority of actuaries, accountants, and bankers produced a report urging drastic economies; Latham and Pugh wrote a minority report that largely reflected the thinking of the TUC and its research department. Although they accepted the majority's contentious estimate of the budget deficit as £120 million and endorsed some economies, they considered the underlying economic difficulties not to be the result of excessive public expenditure, but of post-war deflation, the return to the gold standard, and the fall in world prices. An equitable solution should include taxation of holders of fixed-interest securities who had benefited from the fall in prices."

The cabinet decided to form a committee consisting of Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham to consider the report. On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, describing the May Report as "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read." He argued that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the Gold Standard and devalue sterling. Two days later, Sir Ernest Harvey, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, wrote to Snowden to say that in the last four weeks the Bank had lost more than £60 million in gold and foreign exchange, in defending sterling. He added that there was almost no foreign exchange left.

The cabinet met on 19th August but they were unable to agree on Snowden's proposals. He warned that balancing the budget was the only way to restore confidence in sterling. Snowden argued that if his recommendations were not accepted, sterling would collapse. He added "that if sterling went the whole international financial structure would collapse, and there would be no comparison between the present depression and the chaos and ruin that would face us."

Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis on 23rd August. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through."

On 24th August 1931 MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government.

MacDonald returned to 10 Downing Street and called his final Labour Cabinet. He told them that he had changed his mind about resigning and that he agreed to form a National Government. Sidney Webb recorded in his diary: "He announced this very well, with great feeling, saying that he knew the cost, but could not refuse the King's request, that he would doubtless be denounced and ostracized, but could do no other." When the meeting was over, he asked Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey to stay behind and invited them to join the new government. All three agreed and they kept their old jobs. Other appointments included Stanley Baldwin (Lord President of the Council), Neville Chamberlain (Health), Samuel Hoare (Secretary of State for India), Herbert Samuel (Home Office), Philip Cunliffe-Lister (Board of Trade) and Lord Reading (Foreign Office).

Morgan Philips Price commented: "I found Members delighted that Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden and J. H. Thomas had severed themselves from us by their action. We had got rid of the Right Wing without any effort on our part. No one trusted Mr Thomas and Philip Snowden was recognized to be a nineteenth-century Liberal with no longer any place amongst us. State action to remedy the economic crisis was anathema to him. As for Ramsay Macdonald, he was obviously losing his grip on affairs. He had no background of knowledge of economic and financial questions and was hopelessly at sea in a crisis like this. But many, if not most, of the Labour M.P.s thought that at an election we should win hands down."

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Several leading Labour figures, including Morgan Philips Price, Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Hastings Lees-Smith, Herbert Morrison, William Graham, Tom Shaw, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, Albert Alexander, Margaret Bondfield and Frederick Roberts, lost their seats.

Price became the Labour Party candidate for the Forest of Dean and won the seat in the 1935 General Election. He held the seat until the 1950 General Election when he switched to Gloucestershire West. He retired from the House of Commons in 1959. His memoirs, My Three Revolutions, was published in 1969.

Morgan Philips Price died on 23rd September, 1973.

On this day in 1899 Heinrich Blücher was born in Berlin. His parents were from the working-class and his mother was a laundress. As a young man he joined the Spartacus League, an organization formed by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. He was a gifted, as an orator and as a street fighter. In 1919 he took part in the failed German Revolution.

In 1919 the Spartacus League became the German Communist Party (KPD). Blücher became one of its first members. In 1922 the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) merged with the KPD. Members now included Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Clara Zetkin, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. The KPD abandoned the goal of immediate revolution, and began to contest Reichstag elections, with some success. In the 1924 General Election the party won 62 seats compared to the 100 seats of the Social Democrat Party.

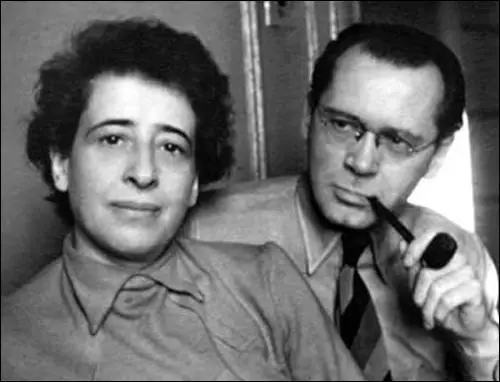

With Blücher, Hannah's world began anew in Paris. Because of who they were, it was still a world of Germans and Jews (a world that had ceased to exist in Germany but was kept alive in France) but it was new because after years of loneliness and disappointment Hannah discovered that love was still a possibility. Blücher was a working-class German leftist in exile; representative of the class of political enemies for whom the Nazis originally invented Dachau.

As a young man at the end of the First World War, he was a Spartacist - a militant revolutionary who fell into the ambit of the newly formed German Communist Party. He studied Marx and Engels and was effective, even gifted, as an orator and as a street fighter,

Ernst Thälmann, replaced Meyer as the Chairman of the KPD in 1925. Thälmann, a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin, willingly put the KPD under the control of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Blücher objected to the Stalinization of the KPD and left the party in 1928. As Clara Zetkin pointed out in a letter to Nikolai Bukharin. "I feel completely alone and alien in this body (KPD), which has changed from being a living political organism into a dead mechanism, which on one side swallows orders in the Russian language and on the other spits them out in various languages, a mechanism which turns the mighty world historical meaning and content of the Russian revolution into the rules of the game for Pickwick Clubs."

Heinrich Blücher fell in love with Hannah Arendt in the spring of 1936. "Arendt was twenty-nine, Blücher thirty-seven... They fell in love almost at first sight. Both were still formally married but separated from their spouses.... Blücher came from a poor, non-Jewish Berlin working-class background. He was an autodidact who had gone to night school but never graduated... Their attraction was at once intellectual and erotic. Blücher was an autodidact but a highly learned one.... Arendt was fascinated by his intellect. Their relationship now ripened in an atmosphere of intense eroticism."

Dwight Macdonald would later describe Blücher's political identity as a "true, hopeless anarchist." Blücher remained friends with left-wing radicals but became increasingly preoccupied with the arts. Blücher became a close friends with Robert Gilbert, a Jewish artist (real name Robert Winterfeld) had fled from Nazi Germany in 1933. Gilbert, a left-wing songwriter, filmmaker, social critic and entertainer, introduced Blücher to Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht.

In September, 1939, Blücher and all male German immigrants in France were deemed potential dangers to French security and were interred in camps in the provinces. He wrote to Arendt that: "As you can imagine, there are quite a few people here who think of nothing but their own personal destiny." However, because he had a loving partner he was able to cope with being in an internment camp: "I love you with all my heart... My beauty, what a gift of happiness it is to have this feeling, and to know that it will last a whole lifetime and will not change except to grow stronger."

Blücher was eventually released and the couple married on 16th January, 1940. At the beginning of May, with the French government expecting a German invasion, ordered that all Germans except the old, the young, and mothers of children report as enemy aliens to internment camps, the men at Stadion Buffalo and the women at the Velodrome d'Hiver. Arendt observed: "Contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings - the kind that are put into concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends."

The German Army invaded on 10th May, 1940, Arendt rightly predicted would soon be turned over to the Germans. She therefore decided to escape from the camp. Those that remained were later deported to Auschwitz. She walked for over 200 miles to Montauban, a meeting point for escapees. Blücher also escaped from his camp during a German air-raid. They were hidden by the parents of Daniel Cohn-Bendit until friends in United States managed to obtain emergency visas for the couple.

Heinrich Blücher and Hannah Arendt arrived in New York City by boat from Lisbon in May 1941. A refugee organization arranged for her to spend two months with an American family in Massachusetts. "The couple who took her in were very high-minded and puritanical; the wife allowed no smoking or drinking in the house... Yet Hannah was impressed by the couple, especially their intense feeling for the democratic political rights and responsibilities of American citizens"

On this day in 1907 women's campaigner Helen Taylor died.

Helen Taylor, the daughter of John Taylor, was born ion 31st July 1831. Her mother, Harriet Taylor, was active in the Unitarian Church and developed radical views on politics. Her parents became friendly with William Johnson Fox, a leading Unitarian minister and early supporter of women's rights.

Her family moved in radical circles and in 1830 Harriet Taylor met the philosopher John Stuart Mill. Taylor was attracted to Mill, the first man she had met who treated her as an intellectual equal. Mill was impressed with Taylor and asked her to read and comment on the latest book he was working on. Over the next few years they exchanged essays on issues such as marriage and women's rights. Those essays that have survived reveal that Taylor held more radical views than Mill on these subjects. She argued: "Public offices being open to them alike, all occupations would be divided between the sexes in their natural arrangements. Fathers would provide for their daughters in the same manner as their sons."

Harriet Taylor was attracted to the socialist philosophy that had been promoted by Robert Owen in books such as The Formation of Character (1813) and A New View of Society (1814). In her essays Taylor was especially critical of the degrading effect of women's economic dependence on men. Taylor thought this situation could only be changed by the radical reform of all marriage laws. Although Mill shared Taylor's belief in equal rights, he favoured laws that gave women equality rather than independence.

In 1833 Helen's mother negotiated a trial separation from her husband. She then spent six weeks with Mill in Paris. On their return Harriet moved to a house at Walton-on-Thames where John Start Mill visited her at weekends. Although Harriet Taylor and Mill claimed they were not having a sexual relationship, their behaviour scandalized their friends. As a result, the couple became socially isolated.

Helen Taylor was very interested in the theatre and from 1856 she took lessons from an experienced actress. She later acted in plays in Newcastle, Doncaster and Glasgow. Her mother suffered from tuberculosis and while in Avignon, seeking treatment for this condition in November, 1858, she died. Harriet Taylor and John Start Mill had been working on a book The Subjection of Women at the time.

Helen Taylor decided to give up her desire to become an actress and devoted herself to caring for her step-father, John Stuart Mill, acting both as his housekeeper and secretary. She also helped him to finish The Subjection of Women. The two worked closely together for the next fifteen years. In his autobiography Mill wrote that "Whoever, either now or hereafter, may think of me and my work I have done, must never forget that it is the product not of one intellect and conscience but of three, the least considerable of whom, and above all the least original, is the one whose name is attached to it."

Frances Power Cobbe commented that Mill's attitude towards Helen was "beautiful to witness, and a fine exemplification on his own theories of the rightful position of women". As well as helping Mill with his books and articles, Helen Taylor was active in the women's suffrage campaign. She was an original member of the Kensington Society that produced the first petition requesting votes for women.

In the 1865 General Election Helen's stepfather, John Stuart Mill was invited to stand as the Radical candidate for the Westminster seat in Parliament. Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies and Bessie Rayner Parkes were enthusiastic supporters of his campaign as he spoke in favour of women having the vote. One politician campaigning against Mill claimed that "if any man but Mr Mill had put forward that opinion he would have been ridiculed and hooted by the press; but the press had not dared to do so with him."

John Stuart Mill won the seat. In the House of Commons Mill campaigned with Henry Fawcett and Peter Alfred Taylor for parliamentary reform and in 1866 presented the petition organised by Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale in favour of women's suffrage. Mill, added an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men.

During the debate on Mill's amendment, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the House of Commons that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Helen Taylor, Lydia Becker and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.