The Boer War

The Boer Wars was the name given to the South African Wars of 1880-1 and 1899-1902, that were fought between the British and the descendants of the Dutch settlers (Boers) in Africa. After the first Boer War, William Gladstone granted the Boers self-government in the Transvaal. (1)

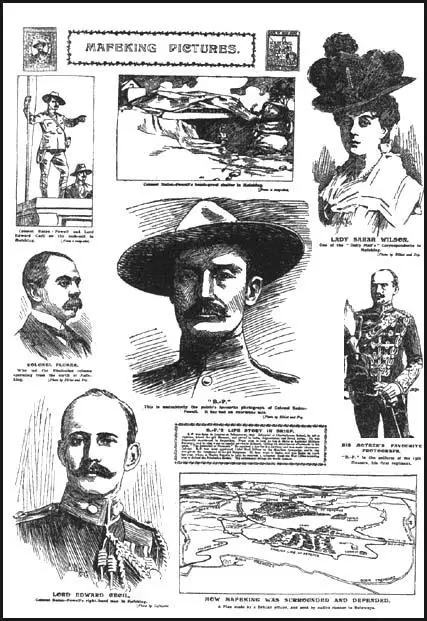

Paul Kruger, resented the colonial policy of Joseph Chamberlain and Alfred Milner which they feared would deprive the Transvaal of its independence. After receiving military equipment from Germany, the Boers had a series of successes on the borders of Cape Colony and Natal between October 1899 and January 1900. Although the Boers only had 88,000 soldiers, led by the outstanding soldiers such as Louis Botha, and Jan Smuts, the Boers were able to successfully besiege the British garrisons at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley. On the outbreak of the Boer War, the conservative government announced a national emergency and sent in extra troops. (2)

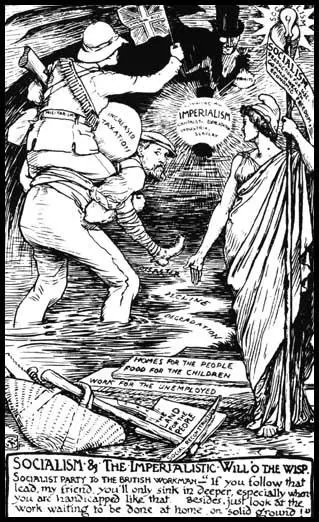

Asquith called for support for the government and "an unbroken front" and became known as a "Liberal Imperialist". Campbell-Bannerman disagreed with Asquith and refused to to endorse the despatch of ten thousand troops to South Africa as he thought the move "dangerous when the the government did not know what it might lead to". David Lloyd George also disagreed with Asquith and complained that this was a war that had been started by Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary. (3)

It has been claimed that Lloyd George "sympathised with the Boers, seeing them as a pastoral community like Welshmen before the industrial revolution". He supported their claim for independence under his slogan "Home Rule All Round" assuming "it would lead to a free association within the British Empire". He argued that the Boers "would only be subdued after much suffering, cruelty and cost." (4)

Lloyd George also saw this anti-war campaign as an opportunity to stop Asquith becoming the next leader of the Liberals. Lloyd George was on the left of the party and had been campaigning with little success for the introduction of old age pensions. The idea had been rejected by the Conservative government as being "too expensive". In one speech he made the point: "The war, I am told, has already cost £16,000,000 and I ask you to compare that sum with what it would cost to fund the old age pension schemes.... when a shell exploded it carried away an old age pension and the only satisfaction was that it killed 200 Boers - fathers of families, sons of mothers. Are you satisfied to give up your old age pension for that?" (5)

The overwhelmingly majority of the public remained fervently jingoistic. David Lloyd George came under increasing attack and after a speech at Bangor on 4th April 1900, he was interrupted throughout his speech, and after the meeting, as he was walking away, he was struck over the head with a bludgeon. His hat took the impact and although stunned, he was able to take refuge in a cafe, guarded by the police.

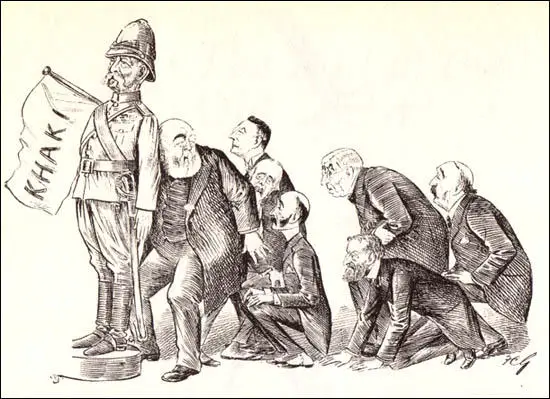

On 5th July, 1900, at a meeting addressed by Lloyd George in Liskeard ended in pandemonium. Around fifty "young roughs stormed the platform and occupied part of it, while a soldier in khaki was carried shoulder-high from end to end of the hall and ladies in the front seats escaped hurriedly by way of the platform door." Lloyd George tried to keep speaking and it was only when some members of the audience began throwing chairs at him that he left the hall. (6)

On 25th July, a motion on the Boer War, caused a three way split in the Liberal Party. A total of 40 "Liberal Imperialists" that included H. H. Asquith, Edward Grey, Richard Haldane, and Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, supported the government's policy in South Africa. Henry Campbell-Bannerman and 34 others abstained, whereas 31 Liberals, led by Lloyd George voted against the motion.

Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, decided to take advantage of the divided Liberal Party and on 25th September 1900, he dissolved Parliament and called a general election. Lloyd George, admitted in one speech he was in a minority but it was his duty as a member of the House of Commons to give his constituents honest advice. He went on to make an attack on Tory jingoism. "The man who tries to make the flag an object of a single party is a greater traitor to that flag than the man who fires upon it." (7)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman with a difficult task of holding together the strongly divided Liberal Party and they were unsurprisingly defeated in the 1900 General Election. The Conservative Party won 402 seats against the 183 achieved by Liberal Party. However, anti-war MPs did better than those who defended the war. David Lloyd George increased the size of his majority in Caernarvon Borough. Other anti-war MPs such as Henry Labouchere and John Burns both increased their majorities. In Wales, of ten Liberal candidates hostile to the war, nine were returned, while in Scotland every major critic was victorious.

John Grigg argues that it was not the anti-war Liberals who lost the party the election. "The Liberals were beaten because they were disunited and hopelessly disorganised. The war certainly added to their confusion, but this was already so flagrant that they were virtually bound to lose, war or no war. The government also had the advantage of improved trade since 1895, which the war, admittedly, turned into a boom. All things considered, the Liberals did remarkably well." (8)

Lord Kitchener, the Chief of Staff in South Africa, reacted to these raids by destroying Boer farms and moving civilians into concentration camps. It was reported: "When the eight, ten or twelve people who lived in the bell tent were squeezed into it to find shelter against the heat of the sun, the dust or the rain, there was no room to stir and the air in the tent was beyond description, even though the flaps were rolled up properly and fastened. Soap was an article that was not dispensed. The water supply was inadequate. No bedstead or mattress was procurable. Fuel was scarce and had to be collected from the green bushes on the slopes of the kopjes by the people themselves. The rations were extremely meagre and when, as I frequently experienced, the actual quantity dispensed fell short of the amount prescribed, it simply meant famine." (9)

Emily Hobhouse, formed the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children in 1900. It was an organisation set up: "To feed, clothe, harbour and save women and children - Boer, English and other - who were left destitute and ragged as a result of the destruction of property, the eviction of families or other incidents resulting from the military operations". Except for members of the Society of Friends, very few people were willing to contribute to this fund. (10)

Hobhouse later wrote: "It was late in the summer of 1900 that I first learnt of the hundreds of Boer women that became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations. That the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance. And from that moment I was determined to go to South Africa in order to render assistance to them". (11)

Hobhouse arrived in South Africa on 27th December, 1900. Hobhouse argued that Lord Kitchener’s "Scorched Earth" policy included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields - to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. Civilians were then forcibly moved into the concentration camps. Although this tactic had been used by Spain (Ten Years' War) and the United States (Philippine-American War), it was the first time that a whole nation had been systematically targeted. She pointed this out in a report that she sent to the government led by Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury. (12)

When she returned to England, Hobhouse campaigned against the British Army's scorched earth and concentration camp policy. William St John Fremantle Brodrick, the Secretary of State for War argued that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps. David Lloyd George took up the case in the House of Commons and accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. (13)

After a meeting with Emily Hobhouse, the leader of the Liberal Party, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, gave his support to Lloyd George against Asquith and the Liberal Imperialists on the subject of the Boer War. In a speech to the National Reform Union he provided a detailed account of Hobhouse's report. He asked "When is a war not a war?" and then provided his own answer "When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa". (14)

The British action in South Africa grew increasingly unpopular and anti-war Liberal MPs and the leaders of the Labour Party saw it as an example of the worst excesses of imperialism. The Boer War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging in May 1902. The peace settlement brought to an end the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as Boer republics. However, the British granted the Boers £3 million for restocking and repairing farm lands and promised eventual self-government. David Lloyd George commented: "They are generous terms for the Boers. Much better than those we offered them 15 months ago - after spending £50,000 in the meantime". (15)

Primary Sources

(1) Emily Hobhouse wrote about how she decided to visit South Africa during the Boer War.

It was late in the summer of 1900 that I first learnt of the hundreds of Boer women that became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations. That the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance. And from that moment I was determined to go to South Africa in order to render assistance to them.

(2) Philip Gibbs, The Pageant of the Years (1946)

The Lord Mayor of London appeared in his robes and made a speech to the crowd. I cannot remember his exact words, but they announced that after intolerable insults from an old man named Kruger, Her Majesty's government had declared war upon the South African Boers. There was terrific and tumultuous cheering. Top hats were flung up after the crowd had sung "God Save the Queen". I don't believe I joined in the cheering. Certainly I did not fling up my top hat. Brought up in the Gladstonian tradition to the Liberals, and being, anyhow, a liberal-minded youth hostile to the loud-mouthed jingoism of the time, I was not swept by enthusiasm for a war which seemed to me, as it did to others, a bit of bullying by the big old British Empire.

(3) George W. Steevens reported the siege of Ladysmith for The Daily Mail (October, 1899)

You hear the squeal of the things all above, the crash and pop all about, and wonder when your turn will come. Perhaps one falls quite near you, swooping irresistibly, as if the devil had kicked it. You come to watch the shells - to listen to the deafening rattle of the big guns, the shrilling whistle of the small, to guess at their pace and their direction. You see now a house smashed in, a heap of chips and rubble; now you see a splinter kicking up a fountain of clinking stone-shivers. This is a dangerous time. If you have nothing else to do, you get shells on the brain, think and talk of nothing else, and finish by going into a hole in the ground before daylight, and hiring better men than yourself to bring you down your meals.

(4) Sarah Wilson was in Mafeking during the Boer War. She reported on the siege for the Daily Mail during April, 1900.

There was a remarkable decrease in the applications at the soup kitchen today, yesterday, and the day before, thanks to the arrival of enormous clouds of locusts, which in ordinary times are unwelcome visitors, but in our present condition were hailed with joy. The natives gathered sacks full, and feed on them tell their stomachs project in prominence of plenitude.

(5) Emily Hobhouse, report on Bloemfontein Concentration Camp (January, 1901)

When the eight, ten or twelve people who lived in the bell tent were squeezed into it to find shelter against the heat of the sun, the dust or the rain, there was no room to stir and the air in the tent was beyond description, even though the flaps were rolled up properly and fastened. Soap was an article that was not dispensed. The water supply was inadequate. No bedstead or mattress was procurable. Fuel was scarce and had to be collected from the green bushes on the slopes of the kopjes by the people themselves. The rations were extremely meagre and when, as I frequently experienced, the actual quantity dispensed fell short of the amount prescribed, it simply meant famine.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)