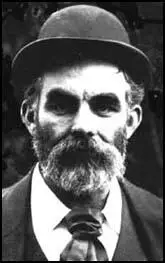

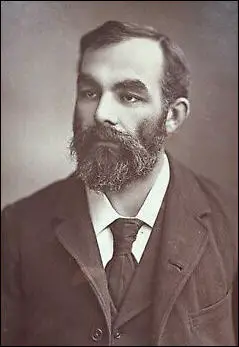

John Burns

John Burns, the sixteenth child of Alexander Burns, a Scottish fitter, and Barbara Smith, was born in Lambeth on 20th October, 1858. His father deserted his mother and his mother took in washing and the family moved to a basement dwelling in Battersea. John attended St Mary's National School but left when he was ten and after a series of short-term jobs was apprenticed as an engineer at Mowlems, a major London contractor.

One of his fellow workers, Victor Delahaye, an exiled former communard and a follower of Karl Marx, introduced Burns to radical writers such as John Stuart Mill, Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin. In 1878 Burns was arrested for holding a political meeting on Clapham Common in defiance of a police prohibition.

In 1879 Burns joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and found employment with the United Africa Company. Horrified by the way the Africans were treated, Burns became convinced that only socialism would remove the inequalities between races and classes. He returned to England in 1881 and soon afterwards formed the Battersea branch of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). One of the first people to join was another young engineer, Tom Mann.

In July 1882 Burns married Martha Charlotte Gale (1861–1936), daughter of a Battersea shipwright. They had one son, Edgar. He developed a reputation as an outstanding public speaker. One member of the SDF described him as "a sort of giant gramophone". According to his biographer, Kenneth D. Brown: "The language Burns used at this time was often cited later as evidence of his revolutionary aspirations, but he was sometimes tempted into excesses because he so revelled in his ability to inspire adulation in a crowd, and many of his words were subsequently taken out of context. Fundamentally, he never wavered in his conviction that social change was the priority, the method of achieving it a secondary consideration. Even before his imprisonment he had shown signs of disenchantment with the SDF's chronic internecine bickering and its desire to engage in class warfare in the House of Commons, rather than seeking some tangible benefits for ordinary people."

Burns was elected to the executive council of the Social Democratic Federation. Some members of the Social Democratic Federation disapproved of the dictorial style of the SDF leader, Henry M. Hyndman. In December 1884 William Morris and Eleanor Marx left to form a new group called the Socialist League. Burns remained in the SDF and in the 1885 General Election was their unsuccessful candidate in Nottingham West. However, his 598 votes dwarfed the total of 59 cast for the two SDF candidates in other constituencies.

The Social Democratic Federation organised a meeting for 13th February, 1887 in Trafalgar Square to protest against the policies of the Conservative Government headed by the Marquess of Salisbury. Sir Charles Warren, the head of the Metropolitan Police wrote to Herbert Matthews, the Home Secretary: "We have in the last month been in greater danger from the disorganized attacks on property by the rough and criminal elements than we have been in London for many years past. The language used by speakers at the various meetings has been more frank and open in recommending the poorer classes to help themselves from the wealth of the affluent." As a result of this letter, the government decided to ban the meeting and the police were given the orders to stop the marchers entering Trafalgar Square.

Henry Hamilton Fyfe was one of the special constables on duty that day: "When the unemployed dockers marched on Trafalgar Square, where meetings were then forbidden, I enrolled myself as a special constable to defend the classes against the masses. The dockers striking for their sixpence an hour were for me the great unwashed of music-hall and pantomime songs. Wearing an armlet and wielding a baton, I paraded and patrolled and felt proud of myself."

The SDF decided to continue with their planned meeting with John Burns, Henry M. Hyndman and Robert Cunninghame Graham being the three main speakers. Edward Carpenter explained what happened next: "The three leading members of the SDF - Hyndman, Burns and Cunninghame Graham - agreed to march up arm-in-arm and force their way if possible into the charmed circle. Somehow Hyndman was lost in the crowd on the way to the battle, but Graham and Burns pushed their way through, challenged the forces of Law and Order, came to blows, and were duly mauled by the police, arrested, and locked up. I was in the Square at the time. The crowd was a most good-humoured, easy going, smiling crowd; but presently it was transformed. A regiment of mounted police came cantering up. The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving. To keep a crowd moving is I believe a technical term for the process of riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening and batoning the people."

Walter Crane was one of those who witnessed this attack: "I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life - only the attack was all on one side. The police, in spite of their numbers, apparently thought they could not cope with the crowd. They had certainly exasperated them, and could not disperse them, as after every charge - and some of these drove the people right against the shutters in the shops in the Strand - they returned again."

The Times took a different view of these events: "It was no enthusiasm for free speech, no reasoned belief in the innocence of Mr O'Brien, no serious conviction of any kind, and no honest purpose that animated these howling toughs. It was simple love of disorder, hope of plunder it may be hoped that the magistrates will not fail to pass exemplary sentences upon those now in custody who have laboured to the best of their ability to convert an English Sunday into a carnival of blood."

Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham were put on trial for their involvement in the demonstration that became known as Bloody Sunday. One of the witnesses at the trial was Edward Carpenter: "I was asked to give evidence in favour of the defendants, and gladly consented - though I had not much to say, except to testify to the peaceable character of the crowd and the high-handed action of the police. In cross-examination I was asked whether I had not seen any rioting; and when I replied in a very pointed way 'Not on the part of the people!' a large smile went round the Court, and I was not plied with any more questions. Cunninghame Graham and Burns were both found guilty and sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment.

Burns was now a well-known labour leader and in the elections for the newly created London County Council, he was elected to represent Battersea. Burns worked very closely with John Benn and together they managed to get a motion passed that stated that in future all Council work should only be awarded to those contractors who agreed to observe trade union standards on wages and working conditions.

In June 1889 he left the Social Democratic Federation after a disagreement with the party's leader, H. Hyndman. Like his friend, Tom Mann, Burns was now convinced that socialism would be achieved through trade union activity rather than by parliamentary elections.

When the London Dock Strike started in August 1889, Ben Tillett asked John Burns to help win the dispute. Burns, a passionate orator, helped to rally the dockers when they were considering the possibility of returning to work. He was also involved in raising money and gaining support from other trade unionists. During the dispute Burns emerged with Tillett and Tom Mann as one of the three main leaders of the strike.

The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but other trade union activists such as Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and Henry Hyde Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands.

Kenneth D. Brown has argued: "While he negotiated skilfully with intractable employers and organized picket lines tirelessly, Burns's major contribution was his oratory which sustained the strikers... The long-drawn-out stoppage and its successful outcome made Burns an internationally known figure. Everywhere his support was coveted to boost the ensuing surge of trade union organization and in 1890 he was elected to the parliamentary committee of the TUC. Burns's moderation in conducting the dock strike earned it considerable sympathy from the wider public and did much to dispel the militant reputation he had acquired in 1886 and 1887."

Henry Snell pointed out: "John Burns was one of the Social Democratic Federation's best speakers. He was then about twenty-five years of age, and in the full strength of his manhood. His power as a popular street-corner orator was probably unequalled in that generation. He had a voice of unusual range, a big chest capacity; and he possessed great physical and nervous vitality. His method of attracting a crowd was, immediately he rose to speak, and for one or two minutes only, to open all the stops of his organ-like voice. The crowd once secured, his vocal energy was modified, but his vitality and masterful diction held his audience against all competitors." Tom Mann added: "He had a splendid voice and a very effective and business-like way of putting a case. He looked well on a platform. He always wore a serge suit, a white shirt, a black tie, and a bowler hat. Surprisingly fluent, with a voice that could fill every part of the largest hall or theatre, and, if the wind were favourable, could reach a twenty-thousand audience in the parks, etc."

However, Beatrice Webb was not impressed with John Burns: "Jealously and suspicion of rather a mean kind is John Burns's burning sin. A man of splendid physique, fine strong intelligence, human sympathy, practical capacity, he is unfitted for a really great position by his utter inability to be a constant for a loyal comrade. He stands absolutely alone. He is intensely jealous of other Labour men, acutely suspicious of all middle-class sympathizers, while his hatred of Keir Hardie reaches about the dimensions of mania. All said and done, it is pitiful to see this splendid man a prey to egotism of the most sordid kind."

In the 1892 General Election John Burns was elected to represent Battersea in the House of Commons. Burns now joined the other socialist who won a seat in the election, James Keir Hardie. Whereas Burns was willing to work closely with the Liberal Party, Hardie argued for the formation of a new working class political party. Burns attended the meeting in 1900 that established the Labour Representation Committee, the forerunner of the Labour Party, but refused to join and continued to align himself to the Liberal Party.

Burns knew that the Liberal Party might win the next election whereas the Labour Party would take a long time before it was in a position to form a government. When the Liberal Party won the 1906 General Election, the new Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, offered John Burns the post of President of the Local Government Board.

Burns, the first member of the working-class to become a government minister, disappointed the labour movement with his period in office. Burns was responsible for only one important piece of legislation, the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909, during his time in government. Burns, who was now earning £5,000 a year, was bitterly attacked in the House of Commons by old comrades such as Fred Jowett, when he argued for no outdoor relief to be given to the poor. Burns was reminded how he had been a strong critic of the Poor Law and the workhouse system when he had been a member of the Social Democratic Federation.

Kenneth D. Brown has pointed out: "It has been generally concluded that Burns's eight years at the Local Government Board were barren. Behind this judgement lies the view, originally propagated by Beatrice Webb, that Burns's civil servants played on his personal vanity, flattering him into becoming an ineffective and reactionary minister. Burns's vanity is not in doubt: when Campbell-Bannerman offered him the Local Government Board, Burns is alleged to have replied that the prime minister had never done a more popular thing. But Mrs Webb's views were heavily influenced by the fact that Burns was the rock on which her ambitious plans for restructuring the poor law foundered. He had long believed that poverty and its related problems were the combined outcome of individual failure and an inadequate social environment. This was reinforced by a strong streak of puritanism which expressed itself in his opposition to smoking, drinking, and gambling."

Burns was retained in the cabinet when Herbert Asquith replaced Henry Campbell-Bannerman as prime minister in 1908. Supporters of Burns point out that he did have his successes. For example, he piloted through the House of Commons the 1910 Census Bill that sought to obtain more information about both family structure and urban conditions in order for the government to develop policies to tackle problems such as infant mortality and slum housing. By 1913 his administrative reforms had resulted in a more effective deployment of medical staff in the infirmaries.

Burns gradually began to question the growth in the Welfare State. He told a conference in August 1913, that the government and charity organisations should not "supersede the mother, and they should not by over-attention sterilise her initiative and capacity to do what every mother should be able to do for herself." Beatrice Webb was furious with this approach to poverty: "Burns is a monstrosity, an enormous personal vanity feeding on the deference and flattery yielded to patronage and power. He talks incessantly, and never listens to anyone except the officials to whom he must listen in order to accomplish the routine work of of his office. Hence he is completely in their hands and is becoming the most hidebound of departmental chiefs." Fred Jowett argued that he had clearly gone over to the other side.

In 1914 Burns was appointed as President of the Board of Trade. However, soon afterwards, the British government decided to declare war on Germany. Burns was opposed to Britain becoming involved in a European conflict and along with John Morley and Charles Trevelyan, resigned from the government. The Daily News reported: "Whether men approve of that action (his resignation) or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... John Burns will doubtless remain in public life. He is still in the prime of his years and as an unofficial citizen he will find again his true sphere of action. We shall need his vigorous sense, his courage and his passion for democracy in the times that are upon us".

Burns later stated: "Why four great powers should fight over Serbia no fellow can understand. This I know, there is one fellow who will have nothing to do with such a criminal folly, the effects of which will be appalling to the welter of nations who will be involved. It must be averted by all the means in our power. Apart from the merits of the case it is my especial duty to dissociate myself, and the principles I hold and the trusteeship for the working classes I carry from such a universal crime as the contemplated war will be. My duty is clear and at all costs will be done."

Burns was appalled when David Lloyd George ousted Herbert Asquith in 1916: "The men who made the war were profuse in their praises of the man who kicked the P.M. out of his office and now degrades by his disloyal, dishonest and lying presence the greatest office in the State. The Gentlemen of England serve under the greatest cad in Europe." Burns, without the support of the Liberal Party or the Labour Party, and aware that the public felt hostile to those politicians who did not fully support Britain's involvement in the First World War, decided not to stand in the 1918 General Election.

Kenneth D. Brown has argued: "This was the effective end of Burns's political career although he did not leave the House of Commons until 1918. There was no obvious political home for him in post-war Britain. He had forfeited the support of the Asquithian Liberals through his anti-war stance and he would not consider supporting Lloyd George, for whom he had a deep antipathy. But neither could Burns, despite a few fanciful entries in his diary, contemplate a return as a Labour candidate, for his stewardship of the Local Government Board, particularly his handling of unemployment and the Poplar poor-law inquiry, had closed that particular door."

In 1919 Andrew Carnegie left Burns an annuity of £1,000. Burns spent the rest of his life on his hobbies: the history of London, book collecting and cricket. He wrote: "Books are a real solace, friendships are good but action is better than all for the moment and for some time great events have been denied me and forward action may not come my way."

John Burns died of heart failure and senile arteriosclerosis at the Bolingbroke Hospital in Wandsworth on 24 January 1943, and was buried in St Mary's Churchyard in Battersea.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Mann, Memoirs, (1923)

John Burns and I became close friends and good comrades. He was two years my junior, but looked older than I. We were both members of the Amalgamated Engineers, he of the West London branch, and I of the Battersea branch. He had a splendid voice and a very effective and business-like way of putting a case. He looked well on a platform. He always wore a serge suit, a white shirt, a black tie, and a bowler hat. Surprisingly fluent, with a voice that could fill every part of the largest hall or theatre, and, if the wind were favourable, could reach a twenty-thousand audience in the parks, etc.

(2) Edward Carpenter, My Days and Dreams (1916)

A socialist meeting had been announced for 3 p.m. in Trafalgar Square, the authorities, probably thinking Socialism a much greater terror than it really was, had vetoed the meeting and drawn a ring of police, two deep, all round the interior part of the Square.

The three leading members of the SDF - Hyndman, Burns and Cunninghame Graham - agreed to march up arm-in-arm and force their way if possible into the charmed circle. Somehow Hyndman was lost in the crowd on the way to the battle, but Graham and Burns pushed their way through, challenged the forces of 'Law and Order', came to blows, and were duly mauled by the police, arrested, and locked up.

I was in the Square at the time. The crowd was a most good-humoured, easy going, smiling crowd; but presently it was transformed. A regiment of mounted police came cantering up. The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving. To keep a crowd moving is I believe a technical term for the process of riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening and batoning the people.

I saw my friend Robert Muirhead seized by the collar by a mounted man and dragged along, apparently towards a police station, while a bobby on foot aided in the arrest. I jumped to the rescue and slanged the two constables, for which I got a whack on the cheek-bone from a baton, but Muirhead was released.

The case came into Court afterwards, and Burns and Graham were sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment, each for "unlawful assembly". I was asked to give evidence in favour of the defendants, and gladly consented - though I had not much to say, except to testify to the peaceable character of the crowd and the high-handed action of the police. In cross-examination I was asked whether I had not seen any rioting; and when I replied in a very pointed way "Not on the part of the people!" a large smile went round the Court, and I was not plied with any more questions.

(3) John Burns, The Great Strike (1889)

Still more important perhaps, is the fact that labour of the humbler kind has shown its capacity to organise itself; its solidarity; its ability. The labourer has learned that combination can lead him to anything and everything. He has tasted success as the immediate fruit of combination, and he knows that the harvest he has just reaped is not the utmost he can look to gain. Conquering himself, he has learned that he can conquer the world of capital whose generals have been the most ruthless of his oppressors.

(4) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Angry Labour leaders announced that, on Sunday, November 13th, 1887, Trafalgar Square would be stormed. Squadrons of military, fully armed, and powerful detachments of police, were drafted there to resist any such attempt. On the appointed day, workers led by Burns and others tried to force a way through the armed ranks, to demonstrate the rights of free speech. Bricks and stones were flung, iron railings crashed on sabres and bayonets, dozens of workmen were wounded, and the attack was beaten off. Burns and others were arrested.

A month or two later, another effort was made to storm the Square, and a workman was killed. Burns made a speech at the funeral, and was again arrested. At his trial at the Old Bailey, H. H. Asquith was Counsel for the Defence. Burns was sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment; later, he and Asquith were Cabinet Ministers together.

(5) John Burns, speech to dock workers (16th August, 1889)

Remember the match girls who won their strike and formed a union; take courage from the gas stokers who only a few weeks ago won the eight hour day.

(6) In his book, Memories and Reflections (1931), Ben Tillett described the work that John Burns did for the Dockers' Strike in 1889.

In his blue reefer suit and white straw hat, familiar to the cartoonist, John Burns lent us his stentorian voice and picturesque personality, and created that legendary John Burns to whose allegiance the retired Cabinet Minister, alive and hearty as I write these lines, has remained faithful ever since. John Burns did a great deal for the workers, and the workers did much for John.

Later Burns won the Battersea seat and joined the Liberal Party, reaching Cabinet rank as the first genuine working man. his magnetic and striking personality made him an outstanding figure in those days. an amazing egoism, a quick brain, a mighty voice and a wonderful strength of body gave vitality to his vanity and bluffness.

(7) Henry Snell first met John Burns in 1883.

John Burns was one of the Social Democratic Federation's best speakers. He was then about twenty-five years of age, and in the full strength of his manhood. His power as a popular street-corner orator was probably unequalled in that generation. He had a voice of unusual range, a big chest capacity; and he possessed great physical and nervous vitality. His method of attracting a crowd was, immediately he rose to speak, and for one or two minutes only, to open all the stops of his organ-like voice. The crowd once secured, his vocal energy was modified, but his vitality and masterful diction held his audience against all competitors.

(8) John Burns, interview in Le Figaro (16th August, 1889)

We go in for progressive reforms. For my part I have two eyes which I make use of, one fixed on the ground on the lookout for practical things immediately realisable, the other looking upward - toward the ideal. I recognise that Socialism has ended its purely theoretical course, and that the hour to construct has come. When I have to mount a staircase I climb up step by step. If I want to go up ten stairs at a time I break my neck - and that is not my intention.

(9) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (12th October, 1893)

Jealously and suspicion of rather a mean kind is John Burns's burning sin. A man of splendid physique, fine strong intelligence, human sympathy, practical capacity, he is unfitted for a really great position by his utter inability to be a constant for a loyal comrade. He stands absolutely alone. He is intensely jealous of other Labour men, acutely suspicious of all middle-class sympathizers, while his hatred of Keir Hardie reaches about the dimensions of mania. All said and done, it is pitiful to see this splendid man a prey to egotism of the most sordid kind.

(10) John Burns, letter to a friend (1896)

I am only doing now what I have ever done; and ever will continue to do - that is adapting past experience to present reform in the light of high ideals and future objects. In this work I have received the opposition of a number of men who only advocate the unobtainable because the immediately possible is beyond their moral courage, administrative ability, and their political prescience.

I must firmly adhere to the views I have held and practice, that Socialism to succeed must be practical, tolerant, cohesive and consciously compromising with Progressive forces running, if not so far, in parallel lines towards its own goal. I don't believe that the man who comes furthest my way and nearest to my programme is my most distant enemy. "He who is not wholly for us is wholly against us" is the plaint of the fool or the fanatic. Judge men less by the labels they wear than by their persistent labour for sure if slow progress.

If "our party right or wron"' is to be the rallying cry of a working class movement then it has assumed the very defects that its advocates decry in others. The recent I.L.P. conference from which I had expected some change in methods and tactics has confirmed my previous views of its leaders.

(11) John Burns, lecture on poverty and local government (7th December 1903)

Individual effort is almost relatively impossible to cope with the big problem of poverty as we see it. I want the municipality to be a helping hand to the man with a desire of sympathy, to help the fallen when it is not in their power to help themselves. I believe the proper business of a Municipality is to do for the individual merged in the mass what the individual cannot do so well alone.

(12) John Burns, speech at a local school's prize-giving ceremony, quoted in the South Western Star (2nd December 1904)

You come before me this morning with clean hands and clean collars. I want you to have clean tongues, clean manners, clean morals and clean characters. I don't want boys to use bad language. I don't want boys to buy cigarettes. I don't want boys to use their pencils for improper writing. Don't hustle old people. I neither drink nor smoke, because my schoolmaster impressed upon me three cardinal virtues; cleanliness in person, cleanliness in mind; temperance.

(13) Fenner Brockway, a member of the Independent Labour Party, later recalled how Fred Jowett attacked John Burns for changing his views on the Poor Law once he became a government minister.

Jowett came into conflict with John Burns over his mean administration of the Poor Law. Twenty-four years earlier Burns had been co-leader with Tillett of the dockers' strike, regarded by the public as a revolutionary, but now he had become the most orthodox President of the Local Government Board, encouraging Poor Law Guardians to refuse outdoor relief to the destitute and to drive them into the workhouse. From this day onwards (Jowett's speech attacking Burns in the House of Commons) Burns lost his reputation among the public as a "Socialist", or even as a "Labour man". He had clearly gone over to the other side.

(14) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (30th October, 1907)

Burns is a monstrosity, an enormous personal vanity feeding on the deference and flattery yielded to patronage and power. He talks incessantly, and never listens to anyone except the officials to whom he must listen in order to accomplish the routine work of of his office. Hence he is completely in their hands and is becoming the most hidebound of departmental chiefs.

(15) John Burns, diary entry (23rd September 1912)

I am depressed rather at the wave of brutality sweeping over the country. The new spirit is manifesting itself in a bad way. Impatience with serious grievance, resistance to solid injustice, revolt even against intolerable wrong certainly but the revolutionary spirit is now evoked and responded to in matters that disciplined patience for a short period would resist and a contemptuous indifference could dispose of.

(16) The Daily News (5th August, 1914)

Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken.

Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... John Burns will doubtless remain in public life. He is still in the prime of his years and as an unofficial citizen he will find again his true sphere of action. We shall need his vigorous sense, his courage and his passion for democracy in the times that are upon us.

(17) John Burns, diary entry (27th July 1914)

Why four great powers should fight over Serbia no fellow can understand. This I know, there is one fellow who will have nothing to do with such a criminal folly, the effects of which will be appalling to the welter of nations who will be involved. It must be averted by all the means in our power.

Apart from the merits of the case it is my especial duty to dissociate myself, and the principles I hold and the trusteeship for the working classes I carry from such a universal crime as the contemplated war will be. My duty is clear and at all costs will be done.

(18) On the 4th September, 1914 C. P. Scott, recorded details of a meeting he had with David Lloyd George.

He (Lloyd George), Beauchamp, Morley and Burns had all resigned from the Cabinet on the Saturday before the declaration of war on the ground that they could not agree to Grey's pledge to Cambon (the French ambassador in London) to protect north coast of France against Germans, regarding this as equivalent to war with Germany. On urgent representations of Asquith he (Lloyd George) and Beauchamp agreed on Monday evening to remain in the Cabinet without in the smallest degree, as far as he was concerned, withdrawing his objection to the policy but solely in order to prevent the appearance of disruption in face of a grave national danger. That remains his position. He is, as it were, an unattached member of the Cabinet.

(19) John Burns was appalled when David Lloyd George ousted Herbert Asquith as prime minister. He wrote about the events in his diary entry (8th December 1916)

The men who made the war were profuse in their praises of the man who kicked the P.M. out of his office and now degrades by his disloyal, dishonest and lying presence the greatest office in the State. The Gentlemen of England serve under the greatest cad in Europe.

(20) John Burns kept a diary for many years. The last entry was on 16th May 1920, over twenty years before his death.

Books are a real solace, friendships are good but action is better than all for the moment and for some time great events have been denied me and forward action may not come my way. I believe, however, that impending events will call us and we must respond but where, with whom, and how?

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)