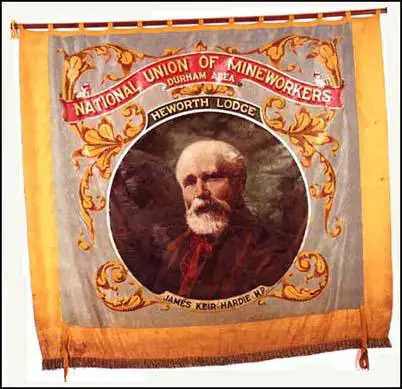

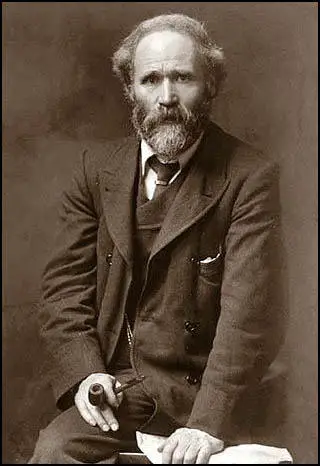

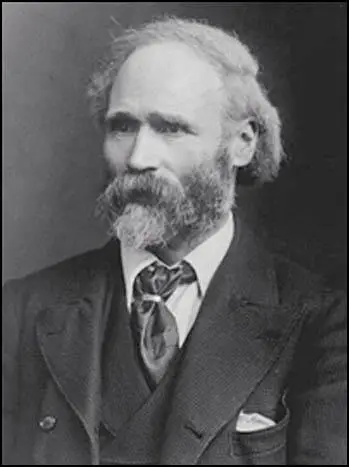

James Keir Hardie

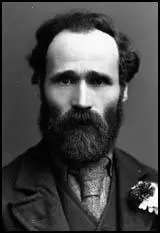

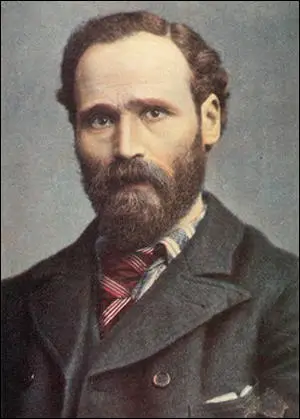

James Keir, the illegitimate son of Mary Keir, a servant from Legbrannock, near Holytown, Lanarkshire, Scotland, was born on 15th August, 1856. It is possible that his father was William Aitkin, a miner. Three years later Mary married David Hardie, a ship's carpenter from Falkirk. After this date he was known as James Keir Hardie. (1)

The family moved to the Partick district of Glasgow. At the age of eight Hardie became a baker's delivery boy. He had to work for twelve and a half hours a day and for his labours received 3s. 6d. a week. With his step-father unemployed, and his mother pregnant, Hardie was the only wage-earner in the family. (2)

In December 1866, his mother and younger brother were seriously ill and he had to nurse them through the night. As a result he was late for work and he was shocked when he was sacked for this offence. "I was discharged, and my fortnight's wages forfeited by way of punishment. The news stupefied me, and I finally burst out crying and begged the shopwoman to intercede with the master for me. The morning was wet, and I had been drenched in getting to the shop, and must have presented a pitiable sight as I stood at the counter in my well-patched clothes. She spoke to the master through a speaking-tube... but he was obdurate, and finally she, out of the goodness of her heart, gave me a piece of bread... For a time I wandered about the streets in the rain, ashamed to go home where there was neither food nor fire, and actually discussing with myself whether the best thing was not to go and throw myself in the Clyde and be done with a life that had so little attractions." (3) Unable to find work in Glasgow, the family moved back to Lanarkshire, and at the age of eleven, Hardie became a coal miner, working for "twelve or fourteen hours a day". Initially he worked as a trapper. "The work of a trapper was to open and close a door which kept the air supply for the men in a given direction. It was an eerie job, all alone for ten long hours, with the underground silence only disturbed by the sighing and whistling of the air as it sought to escape through the joints of the door." (4) Hardie, who never attended school, was completely illiterate until his mother began to teach him to read. His friend, Philip Snowden, explained why this happened: "Keir Hardie had no schooling as a boy. He told me once what drove him to learn to write. When a youth, he went to join the Good Templers. He was unable to sign his name on the membership pledge, and he was so ashamed that he set to work to learn to write." (5) Although Hardie worked 12 hours a day down the mine, he still found time for his studies and by the age of seventeen had learnt to write from a man who provided evening classes to miners: "The teacher was genuinely interested in his pupils and did all he could for them with his limitations of time and equipment. There was no light provided in the school and the pupils had to bring their own candles. Learning had now a kind of fascination for the boy". (6) Hardie began to read newspapers and discovered how some workers were attempting to improve their wages and working conditions by forming trade unions. Hardie helped join a union at his colliery and in 1880 took part in the first ever strike of Lanarkshire miners. This led to his dismissal, and he moved to Old Cumnock. (7) Hardie became a member of the Temperance Society. He met and married Lillie Wilson, a fellow campaigner. As Fran Abrams has pointed out: "He (Hardie) enjoyed the company of women, and Lillie was not the first girl to catch his eye. The marriage was not always a source of joy to either party... for Hardie, politics always came first. The day after his wedding he attended a political rally and set the pattern for the rest of his married life. While he travelled the globe in pursuit of his causes, Lillie was left at home, struggling to bring up a growing family." (8) Hardie read the works of Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Charles Dickens in order to develop his writing style. He "acquired the skills of Pitman's shorthand by scratching out the characters on a blackened slate with the wire used by miners to adjust the wicks of their lamps, in the dark depths of a Lanarkshire pit". He also began having articles published in a local newspaper. (9) In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages. Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. In the summer of 1880, the Hamilton miners defied their union and went on strike against a wage reduction. The strike was crushed, but Hardie was appointed secretary for the recently formed Ayrshire Miners' Union. (10) A friend at this time claimed that although he never drank alcohol he was good company: "A Puritan he was in all matters of absolute right or wrong, and could not be made to budge from what seemed to him to be the straight path. But with that limitation he was one of the most companionable of men. He could sing a good song, and dance and be merry with great abandon." (11) James Mavor met Keir Hardie for the first time in 1879: "When I first met him he was an alert, good-looking young man - reddish hair, ruddy complexion, honest but ecstatic eyes, average stature, very fastidious about his dress... Hardie looked like an artist, and indeed in general his point of view was that of an artist... Although his early education had been somewhat neglected, Hardie had the talent for letters which seems to be indigenous in Ayrshire. He was a creature of impulse. His impulses were always genuine, no matter how mistaken might be the judgments associated with them... He never fell into the habits of his fellows, but identified himself rather with the intellectual and artistic proletariat than with any faction of the middle class. This was no pose, but was the simple outcome of his nature. He was the only really cultivated man in the ranks of any of the Labour parties." (12) In 1882 Keir Hardie met Henry George, the American author of Our Land and Land Policy (1870) and Progress and Poverty (1877). His friend Philip Snowden later argued: "Keir Hardie told me that it was Progress and Poverty which gave him his first ideas of socialism... No book ever written on the social problem made so many converts. Economic facts and theories have never been presented in such an attractive way. Although Henry George was not a socialist, his book led many of his readers to socialism." (13) Hardie admitted that his conversion to socialism was a "protracted process" and had "no real base in economics". He described socialism as "more an affair of the heart than of the intellect" and saw it as a political system that would protect and support weaker members of the community. He agreed with Karl Marx that capitalists were a "corrupt class" and "endorsed his vision of the historical struggle of the workers" but rejected his ideas on the need for revolution to change society. (14) In the 1880s working-class political representatives stood in parliamentary elections as Liberal-Labour candidates. After the 1885 General Election there were eleven of these Liberal-Labour MPs. William Gladstone, the prime minister, offered one of these MPs, Henry Broadhurst, a former stonemason, the post of Under-Secretary at the Home Office. When Broadhurst accepted the post he became the first working man to become a government minister. Broadhurst's loyal support of the Liberal government upset some trade union leaders. When Broadhurst argued against the eight-hour day, Keir Hardie remarked that the minister was more Liberal than Labour. (15) In 1886 Keir Hardie was appointed secretary of the Scottish Miners' Federation. The following year, Hardie began publishing a monthly newspaper called The Miner. Its first number appeared in January, 1887, and it was published for two years, with Hardie supplying about a third of its content: "It was a very remarkable paper, and to those who are fortunate enough to possess the two volumes, it mirrors in a very realistic way the social conditions of the collier folk of that time, and also throws considerable light on the many phases and aspects of the general Labour movement in the days when it was gropingly feeling its way through many experiments and experiences towards political self-reliance and self-knowledge". (16) The newspaper advocated a Scottish miners' federation and attacked the coal-owners for the bloody suppression of the Lanarkshire workers that took place that year. (17) Hardie also attempted to use the newspaper to give the miners a political education. "So long as men are content to believe that Providence has sent into the world one class of men saddled and bridled, and another class booted and spurred to ride them, so long will they be ridden; but the moment the masses come to feel and act as if they were men, that moment the inequality ceases." (18) However, Hardie rejected the theories being advocated by communists . In one speech he pointed out "I reject what seems to be the crude notion of a class war, because class consciousness leads nowhere... The watchword of socialism is not class consciousness but community consciousness." (19) During this period Hardie met Robert Cunninghame Graham. He later recorded: "Keir Hardie... was then about thirty years of age... His hair was already becoming thin at the top of the head, and receding from the temples. His eyes were not very strong. At first sight he struck you as a remarkable man. There was an air of great benevolence about him, but his face showed the kind of appearance of one who has worked hard and suffered, possibly from inadequate nourishment in his youth. He was active and alert and appeared to be full of energy, and as subsequent events proved, he had an enormous power of resistance against long, hard and continual work. I should judge him to have been of a very nervous and high-strung temperament. At that time, and I believe up to the end of his life, he was an almost ceaseless smoker... He was a very strict teetotaller and remained so to the end, but he was not a bigot on the subject and was tolerant of faults in the weaker brethren. Nothing in his address or speech showed his want of education in his youth. His accent was of Ayrshire... His voice was high-pitched but sonorous and very far-carrying at that time. He never used notes at that time, and I think never prepared a speech, leaving all to the inspiration of the moment. This suited his natural, unforced method of speaking admirably." (20) As Kenneth O. Morgan has pointed out: "By the end of 1887 Hardie's political outlook had clearly changed from orthodox Liberalism to a kind of socialism.... Historians have differed on the precise significance of this conversion. Some regard him as an ideological socialist from then on. Most, however, see his socialism as an undoctrinaire outgrowth of advanced Liberalism, and as ethical rather than economic in its basis. He was never a Marxist. But from 1887 he was clearly an apostle of the gospel of socialism and the political independence of labour." (21) Hardie was also getting very disillusioned with the Liberal Party. The Eight Hours Amendment was defeated in the House of Commons due partly to the action of the Liberal-Labour members from mining districts, Thomas Burt, Charles Fenwick and William Abraham. One notable amendment of the Bill, secured very largely through pressure by people like Hardie was the prohibition of the employment of boys under twelve. Hardie wrote: "What a difference from the time when children were taken into the pit almost as soon as they were out of the cradle." (22) Keir Hardie came to the conclusion that the working-class needed its own political party. With the support of Robert Smillie, the leader of the Lanarkshire miners, Hardie began advocating socialism and in 1888 stood as the Independent Labour candidate for the constituency of Mid-Lanark. Hardie first attempt to enter the House of Commons ended in failure. However, as his friend, Tom Johnson, made clear, this marked a turning point in history: "He had set the idea of political independence before the workers, and although maligned, traduced, and slandered in the Liberal Press with almost savage ferocity, he polled 712 votes." (23) In August 1888, Hardie resigned from the Liberal Party and helped to establish the Scottish Labour Party. He did not want a socialist party on the lines of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). He wanted a party which would attract radicals, dissatisfied liberals, trade unionists and social reformers concerned about the plight of children. A programme was agreed that included the "prohibition of the liquor traffic, the abolition of the House of Lords, the nationalization of land, minerals, railways, waterways and tramways, free education, boards to provide food for children and taxes on incomes over £300." (24) Hardie also changed the name of his newspaper from The Miner to The Labour Leader. He attended the inaugural Second International meetings in Paris in July, 1888, where he joined up again with Tom Mann, the leader of the Eight Hour League, that was influential in convincing the trade union movement to adopt the statutory eight-hour day as one of its core policies. Mann commented in his autobiography that "our relations were always harmonious". They joined forces in persuading the conference to allow anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin to address delegates. (25) Hardie also met up with Richard Pankhurst and his wife, Emmeline Pankhurst. He was introduced to their three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. Sylvia, who was only seven years old at the time, later recalled: "Kneeling on the stairs to watch him, I felt that I could have rushed into his arms; indeed it was not long before the children in the houses where he stayed had climbed to his knees. He had at once the appearance of great age and vigorous youth." (26) Keir Hardie accepted the offer of standing at West Ham South constituency in London's industrial East End. It was a area much affected by the "new unionism" among unskilled workers. He moved to London in 1891, and resigned as secretary of the Ayrshire Miners. In the 1892 General Election the Liberal Party did not put up a candidate and it was a straight fight with the Conservative candidate. Hardie won by 5,268 votes to 4,036. (27) Hardie, the country's first socialist member of the House of Commons, took his seat on 3rd August, 1892. The tradition at that time was for MPs to wear long black coats, a silk top hat and starched wing collar. Hardie created a sensation by entering Parliament in a tweed suit, a red tie, and a workman's peaked cap. John Burns claimed that the check cloth was so broad that "you could have played draughts on it". (28) Thomas Threlfall of the Trade Union Congress attacked Hardie for his behaviour. He said that previously trade union men in the House of Commons had "demonstrated that working men could come like gentlemen". He added that Hardie had outraged the sentiment of Labour and that he did serious injury to his own reputation by going to the House of Commons dressed in the manner he did... because the House of Commons is the first assembly of gentlemen in the world." (29) In the House of Commons Hardie began advocating policies that had first been put forward by Tom Paine in his book Rights of Man in 1791. Hardie argued that people earning more than a £1,000 a year should pay a higher rate of income-tax. Hardie believed this extra revenue should be used to provide old age pensions and free schooling for the working class. Hardie also campaigned for the reform of Parliament. He was a supporter of the women's suffrage movement, the payment of MPs and the abolition of the House of Lords. Keir Hardie, helped to establish the Independent Labour Party in 1893. It was decided that the main objective of the party would be "to secure the collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". Leading figures in this new organisation included Robert Smillie, George Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann, George Barnes, Pete Curran, John Glasier, Katherine Glasier, H. H. Champion, Ben Tillett, Philip Snowden, Edward Carpenter and Ramsay Macdonald. He used The Labour Leader to develop policy, to give advice on how to conduct meetings, and how to organize groups such as Socialist church groups and Sunday School classes. (30) On Saturday, 23rd June, 1894, there was a massive explosion in a colliery near Pontypridd, Wales. Two days later, Hardie suggested in the House of Commons that a message of condolence to the relatives of the 251 coal miners that had been killed in the accident, should be added to an address of congratulations on the birth of a royal heir (the future Edward VIII). When the request was refused, Hardie made a speech attacking the privileges of the monarchy. (31) J. R. Clynes later commented: "The House rose at him like a pack of wild dogs. His voice was drowned in a din of insults and the drumming of feet on the floor. But he stood there, white-faced, blazing-eyed, his lips moving, though the words were swept away." Later he wrote: "The life of one Welsh miners of greater commercial and moral value to the British nation than the whole Royal crowd put together." (32) In 1895 the ILP had 35,000 members. However, in the 1895 General Election the ILP put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. All the candidates were defeated, including Hardie, who because of his socialist views, had lost the support of the local Liberal Party. However, the ILP began to have success in local elections. Over 600 won seats on borough councils and in 1898 the ILP joined with the the SDF to make West Ham the first local authority to have a Labour majority. (33) In 1896 Emmeline Pankhurst, a member of the Independent Labour Party in Manchester, began organizing Sunday open-air meetings in the local park. The local authority declared that these meetings were illegal and speakers began to be arrested and imprisoned. Pankhurst invited Hardie to speak at one of these meetings. On 12th July, 1896, over 50,000 turned up to hear Hardie, but soon after he started speaking, he was arrested. The Home Secretary, worried by the publicity Hardie was getting, intervened, and used his power to have the leader of the ILP released. Although raised as an atheist, Hardie was converted to Christianity in 1897. A lay preacher for the Evangelical Union Church, Hardie was also active in the Temperance Society. Hardie considered himself to be a Christian Socialist: "I have said, both in writing and from the platform many times, that the impetus which drove me first into the Labour movement, and the inspiration which has carried me on in it, has been derived more from the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth than from all other sources combined." (34) On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain (the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the Fabian Society, met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Keir Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). The committee included two members from the ILP (Keir Hardie and James Parker), two from the SDF (Harry Quelch and James Macdonald), one member of the Fabian Society (Edward R. Pease), and seven trade unionists (Richard Bell, John Hodge, Pete Curran, Frederick Rogers, Thomas Greenall, Allen Gee and Alexander Wilkie). (35) Whereas the ILP, SDF and the Fabian Society were socialist organizations, the trade union leaders tended to favour the Liberal Party. As Edmund Dell pointed out in his book, A Strange Eventful History: Democratic Socialism in Britain (1999): "The ILP was from the beginning socialist... but the trade unions which participated in the foundation were not yet socialist. Many trade union leaders were, in politics, inclined to Liberalism and their purpose was to strengthen labour representation in the House of Commons under Liberal party auspices. Hardie and the ILP nevertheless wished to secure the collaboration of trade unions. They were therefore prepared to accept that the LRC would not at the outset have socialism as its objective." (36) Henry Pelling argued: "The early components of the Labour Party formed a curious mixture of political idealists and hard-headed trade unionists: of convinced Socialists and loyal but disheartened Gladstonians". (37) Ramsay MacDonald was chosen as the secretary of the Labour Representation Committee. As he was financed by his wealthy wife, Margaret MacDonald, he did not have to be paid a salary. The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Keir Hardie was elected as MP for Merthyr Tydfil, an industrial town in South Wales. However, the only other ILP member to win a seat was Richard Bell. (38) Hardie promoted the cause of women's suffrage. Not all of his fellow socialists shared this commitment, as they believed members of the National Union of Suffrage Societies were primarily concerned with winning the vote for middle-class women, whereas they believed that it should be granted to all adults. Hardie's friend, John Bruce Glasier, recorded in his diary after a meeting with Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst, that they were guilty of "miserable individualist sexism". (39) In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst joined forces with her three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst to establish the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Hardie gave his support to the WSPU but this brought him into conflict with other members of the Labour Party. As they pointed out, the WSPU wanted votes for women on the same terms as men, and specifically not votes for all women. They considered this unfair as in 1903 only a third of men had the vote in parliamentary elections. Sylvia Pankhurst was a student at the Royal College of Art and she began spending a lot of time with Keir Hardie. According to the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003): "The young student, now aged twenty-four, had fallen for the fifty-year-old politician in a manner which went far beyond mere admiration or friendship. As the relationship developed, the complexity of these feelings became clearer. Sylvia saw Hardie as part political hero, part father-figure and part potential lover. Gradually he began to return her feelings... Hardie helped her move into cheaper lodgings, soothed her furrowed brow and took her out for a cheering meal. From then on Sylvia often visited him at the House of Commons and the two walked together in St James's Park or spent the evening at Nevill's Court. Quite how they dealt with the fact that he was already married is not entirely clear." (40) At the 1906 General Election thirty-one Labour Party candidates did not have to face a Liberal opponent. In a large number of seats the LRC did not stand against Liberals who had a good chance against the Conservative candidate. The Liberals, led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman, won a landslide victory, winning 377 seats and a majority of 84 over all other parties. The Conservatives lost more than half their seats, including that of its leader, Arthur Balfour. The LRC won twenty-nine seats. This included Ramsay MacDonald (Leicester) Keir Hardie (Merthyr Tydfil), Philip Snowden (Blackburn), Arthur Henderson (Barnard Castle), George Barnes (Glasgow Blackfriars), Will Thorne (West Ham), Fred Jowett (Bradford), David Shackleton (Clitheroe), Will Crooks (Woolwich), J. R. Clynes (Manchester North-East), John Hodge (Gorton), Stephen Walsh (Ince) and James Parker (Halifax). At a meeting on 12th February, 1906, the group of MPs decided to change from the LRC to the Labour Party. Hardie was elected chairman and MacDonald was selected to be the party's secretary. Despite providing the two leaders the party, only six of the MPs were supporters of the ILP. (41) This success was due to the secret alliance with the Liberal Party. This upset left-wing activists as they wanted to use elections to advocate socialism. (42) However, of their 29 MPs only 18 were socialists. Hardie was elected chairman of the party by one vote, against Shackleton, the trade union candidate. His victory was based on recognition of his role in forming the Labour Party rather than his socialism. (43) Some people in the party were worried about the new dominance of the trade union movement. The Clarion newspaper wrote: "There is probably not more than one place in Britain (if there is one) where we can get a Socialist into Parliament without some arrangement with Liberalism, and for such an arrangement Liberalism will demand a terribly heavy price - more than we can possibly afford." (44) Keir Hardie told the 1907 party conference: "I thought the days of my pioneering were over but of late I have felt, with increasing intensity, the injustice inflicted on women by our present laws. The Party is largely my own child and I cannot part from it lightly, or without pain; but at the same time I cannot sever myself from the principles I hold. If it is necessary for me to separate myself from what has been my life's work, I do so in order to remove the stigma resting upon our wives, mothers and sisters of being accounted unfit for citizenship." (45) In the House of Commons Hardie complained about the way members of the Women's Social and Political Union were treated in prison. "That there is difference of opinion concerning the tactics of the militant Suffragettes goes without saying, but surely there call be no two opinions concerning the horrible brutality of these proceedings? Women, worn and weak by hunger, are seized upon, held down by brute force, gagged, a tube inserted down their throats and food poured or pumped into the stomach." (46) Hardie was not very good with dealing with internal rivalries within the party, and in 1908 resigned as leader. Hardie spent the next few years trying to build up the Labour Party. He was also committed to international socialism and toured the world arguing for equality. Speeches he made in favour of self-rule in India and equal rights for non-whites in South Africa resulted in riots and he was attacked in newspapers as a troublemaker. (47) In 1909 Hardie and Sylvia Pankhurst rented a cottage in Penshurst, Kent. They met there as often as his busy schedule permitted. According to Fran Abrams: "During one of these interludes he begged her not to go back to prison. The thought of the feeding tubes and the violence with which they were used was already making him ill - how much worse would it be if it were her?" (48) The 1910 General Election saw 40 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons. Hardie agreed to become leader again. Hardie's views were not always shared by other Labour MPs. Many disagreed with Hardie's support of women's suffrage. Although opposed to the use of violence, Hardie understood the reasons why some had adopted militant tactics and worked very closely with socialists in the WSPU. In 1910 George Barnes replaced Hardie as leader of the Labour Party in the House of Commons. Some of the senior figures in the Labour Party, including Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, supported the campaign of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Lansbury was especially critical of the Cat & Mouse Act and was ordered to leave the building after shaking his fist in the face of Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, and told him that he was "beneath contempt" because of his treatment of WSPU prisoners. In October, 1912, Lansbury decided to draw attention to the plight of WSPU prisoners by resigning his seat in Parliament and fighting a by-election in favour of votes for women. Lansbury was defeated by 731 votes. (49) Ramsay MacDonald, the new Labour leader, rejected their use of violence: "I have no objection to revolution, if it is necessary but I have the very strongest objection to childishness masquerading as revolution, and all that one can say of these window-breaking expeditions is that they are simply silly and provocative. I wish the working women of the country who really care for the vote ... would come to London and tell these pettifogging middle-class damsels who are going out with little hammers in their muffs that if they do not go home they will get their heads broken." (50) Most of the women in the Labour Party supported the NUWSS. Ada Nield Chew attacked the policy of the WSPU: "The entire class of wealthy women would be enfranchised, that the great body of working women, married or single, would be voteless still, and that to give wealthy women a vote would mean that they, voting naturally in their own interests, would help to swamp the vote of the enlightened working man, who is trying to get Labour men into Parliament." (51) Several campaigners for votes for women, such as Charlotte Despard, Isabella Ford, Katherine Glasier, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jessie Stephen and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy were members of the Independent Labour Party and for a long time had been active in socialist politics. However, although most Labour MPs supported the principle of women's suffrage they refused to treat it as a priority. (52) In January 1913, May Billinghurst, a woman who was severely disabled, was found guilty of taking part in a WSPU demonstration and sentenced to eight months in Holloway Prison. Billinghurst immediately went on hunger-strike: "My head was forced back and a tube jammed down my nose. It was the most awful torture. I groaned with pain and I coughed and gulped the tube up and would not let it pass down my throat. Then they tried the other nostril and they found that was smaller still and slightly deformed, I suppose from constant hay-fever. The new doctor said it was impossible to get the tube down that one so they jammed it down again through the other and I wondered if the pain was as bad as child-birth. I just had strength and will enough to vomit it up again and I could see tears in the wardresses' eyes." After protests about Billinghurst's treatment by Hardie and George Lansbury in the House of Commons, and comments from the prison doctor, who feared she would die of a heart-attack, she was released from prison. Votes for Women carried an article by Christabel Pankhurst that argued: "Keir Hardie's magnificent protest in the House of Commons against force feeding will be remembered when much that had occurred in the late Parliament has been forgotten." Isabella Ford, a member of the NUWSS, commented: "His extraordinary sympathy with the women's movement, his complete understanding of what it stands for, were what first made me understand the finest side of his character. In the days when Labour men neglected and slighted the women's cause or ridiculed it, Hardie never once failed us, never once faltered in his work for us. We women can never forget what we owe him." (53) Hardie also disagreed with many members of the Labour Party over the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Hardie was a pacifist and tried to organize a national strike against Britain's participation in the war. He issued a statement that argued: "The long-threatened European war is now upon us. You have never been consulted about this war. The workers of all countries must strain every nerve to prevent their Governments from committing them to war. Hold vast demonstrations against war, in London and in every industrial centre. There is no time to lose. Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!" (54) Despite being seriously ill, Hardie took part in several anti-war demonstrations and as a result some of his former supporters denounced him as a traitor. One supporter of the war asked Hardie: "Where are your two boys?" Hardie replied that he would rather see them put against a wall and shot than see them go to war." J. R. Clynes was one of his many friends who refused to support Hardie's anti-war stance: "Hardie became a broken man. For the next twelve months the old dominant figure we had known was seen no more in the corridors of the House of Commons; he shrank into a travesty of his former self, never spoke in debates and said little to anyone. The great leader of Labour was dying on his feet. We all loved and respected him; it was a great grief to us that our attitude to war was driving the sword into his heart; but between our conscience and our friend there was only one choice." (55) In December, 1914, Hardie had a stroke. He returned to the House of Commons in February, 1915, but he had not made a full-recovery and his friend, John Bruce Glasier, reported that he kept falling asleep during meetings. Another friend said that Hardie began suffering from delusions. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "I knew that Keir Hardie had been failing in health since the early days of the war. The great slaughter, the rending of the bonds of international fraternity, on which he had built his hopes, had broken him. Quite early he had a stroke in the House of Commons after some conflict with the jingoes. When he left London for the last time he had told me quietly that his active life was ended, and that this was forever farewell, for he would never return. In his careful way he arranged for the disposal of his books and furniture and gave up his rooms, foreseeing his end, and fronting it without flinching or regret." (56) James Keir Hardie returned to Scotland and died in hospital in Glasgow on 25th September, 1915.Keir Hardie - Trade Unionist

Ayrshire Miners' Union

Scottish Miners' Federation

Socialism

Member of Parliament

The Labour Party

1906 General Election

1910 General Election

Primary Sources

(1) James Keir Hardie, From Serfdom to Socialism (1907)

I was discharged, and my fortnight's wages forfeited by way of punishment. The news stupefied me, and I finally burst out crying and begged the shopwoman to intercede with the master for me. The morning was wet, and I had been drenched in getting to the shop, and must have presented a pitiable sight as I stood at the counter in my well-patched clothes. She spoke to the master through a speaking-tube... but he was obdurate, and finally she, out of the goodness of her heart, gave me a piece of bread... For a time I wandered about the streets in the rain, ashamed to go home where there was neither food nor fire, and actually discussing with myself whether the best thing was not to go and throw myself in the Clyde and be done with a life that had so little attractions.

(2) William Stewart, J. Keir Hardie: A Biography (1921)

Almost immediately on coming to Newarthill the boy, now ten years of age, went down the pit as trapper to a kindly old miner, who before leaving him for the first time at his lonely post, wrapped his jacket round him to keep him warm. The work of a trapper was to open and close a door which kept the air supply for the men in a given direction. It was an eerie job, all alone for ten long hours, with the underground silence only disturbed by the sighing and whistling of the air as it sought to escape through the joints of the door. A child's mind is full of vision under ordinary surroundings, but with the dancing flame of the lamps giving life to the shadows, only a vivid imagination can conceive what the vision must have been to this lad.

At this time he began to attend Eraser's night school at Holytown. The teacher was genuinely interested in his pupils and did all he could for them with his limitations of time and equipment. There was no light provided in the school and the pupils had to bring their own candles. Learning had now a kind of fascination for the boy. He was very fond of reading, and a book, The Races of the World, presented to him by his parents, doubtless awakened in his mind an interest in things far beyond the coal mines of Lanarkshire. His mother gave him every encouragement. She had a

wonderful memory. "Chevy Chase" and all the well-known ballads and folk-lore tales were recited and rehearsed round the winter fire. In this manner and under these diverse influences did the future Labour leader pass his boyhood, absorbing ideas and impressions which remained with him ever afterwards.

(3) James Keir Hardie, From Serfdom to Socialism (1907)

This generation has grown up ignorant of the fact that socialism is as old as the human race. When civilization dawned upon the world, primitive man was living his rude Communistic life, sharing all things in common with every member of the tribe. Later when the race lived in villages, man, the communist, moved about among the communal flocks and herds on communal land. The peoples who have carved their names most deeply on the tables of human story all set out on their conquering career as communists, and their downward path begins with the day when they finally turned away from it and began to gather personal possessions. When the old civilizations were putrefying, the still small voice of Jesus the Communist stole over the earth like a soft refreshing breeze carrying healing wherever it went.

(4) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

Keir Hardie had no schooling as a boy. He told me once what drove him to learn to write. When a youth, he went to join the Good Templers. He was unable to sign his name on the membership pledge, and he was so ashamed that he set to work to learn to write.

The moving impulse of Keir Hardie's work was a profound belief in the common people. He believed in their capacity, and he burned with indignation at their unmerited sufferings. He never argued on the platform the economic theories of socialism. His socialism was a great human conception of the equal right of all men and women to the wealth of the world and to the enjoyment of the fullness of life.

He had a touching sympathy for the helpless. I have seen his eyes fill with tears at the news of the death of a devoted dog. He carried to his end an old silver watch he had worn in the mine, which bore the marks of the teeth of a favourite pit pony, made by the futile attempt on its part to eat it.

(5) James Mavor, My Windows on the Street of the World (1923)

When I first met him he was an alert, good-looking young man - reddish hair, ruddy complexion, honest but ecstatic eyes, average stature, very fastidious about his dress. Jagerism did not become popular until after this date, but Hardie had independently adopted the light brown finely woven materials which the Jagerites affected

later. Hardie looked like an artist, and indeed in general his point of view was that of an artist. He was not the least of a politician, and he was simply thrown away in Parliament. He could not be disciplined into a party man, and no party could have retained him. In every respect, excepting in practical politics, he was superior to every one of the Labour members and to many other members of Parliament, yet in Parliament he was not a success...Although his early education had been somewhat neglected, Hardie had the talent for letters which seems to be indigenous in Ayrshire. He was a creature of impulse. His impulses were always genuine, no matter how mistaken might be the judgments associated with them. The trade-union secretary and Labour member of his time fell very readily into the ways of living and the modes of thinking of the commercial and industrial stratum of the lower middle class with which they came into contact and unconsciously imitated. Hardie was quite different. He never fell into the habits of his fellows, but identified himself rather with the intellectual and artistic proletariat than with any faction of the middle class. This was no pose, but was the simple outcome of his nature. He was the only really cultivated man in the ranks of any of the Labour parties.

(4) Robert Cunninghame Graham, West Bromwich Labour Tribune (May 1887)

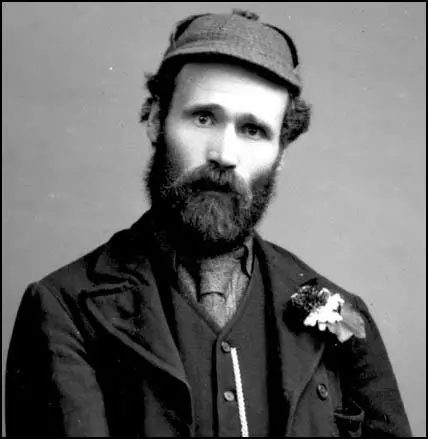

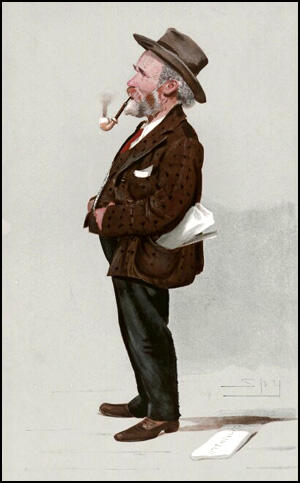

A working man in Parliament should go to the House of Commons in his workaday clothes. He should address the Speaker on labour questions and give utterance to the same sentiments in the same language and in the same manner that he is accustomed to utter his sentiments to the local Radical Club. Above all, he should remember that all the Conservatives and the greater portion of Liberals are joined together in the interest of Capital versus Labour.

(5) James Keir Hardie, election address (10th January 1906)

Religion should be voluntary. Let every denomination have whatever facilities can be given outside of school hours for imparting religious instruction, place all denominations on an equality and lift our whole system of education beyond the reach of sectarian disputes.

(6) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs: 1869-1924 (1937)

One day in June, 1894, in the Commons, an address of congratulations was moved on the birth of a son to the then Duchess of York. This child later became King Edward VIII. Hardie moved an amendment to this address, crying out that over two hundred and fifty men and boys had been killed on the same day in a mining disaster, and claiming that this great tragedy needed the attention of the House of Commons far more than the birth of any baby. He had been a miner himself; he knew. The House rose at him like a pack of wild dogs. His voice was drowned in a din of insults and the drumming of feet on the floor. But he stood there, white-faced, blazing-eyed, his lips moving, though the words were swept away. Later he wrote: "The life of one Welsh miners of greater commercial and moral value to the British nation than the whole Royal crowd put together."

(7) Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story: The Life of Alfred Salter (1949)

Whilst still at the Settlement, Salter had been inspired by Keir Hardie's courageous opposition to the Boer War and all that he had heard since of the I.L.P. leader had increased his admiration. Hardie was a Christian and approached Socialism from human, moral and ethical motives. He was also a temperance man and the doctor had been stirred by the decision of the members of the Parliamentary Labour Party, under their leader's influence, to abstain from alcoholic drinks when on duty at the House of Commons. Above all, Salter was impressed by the Socialist fight which the newly emerged Labour Party, and especially its influential ILP, personalities, were making in Parliament. They had initiated the demand for the school-feeding of hungry children, for old-age pensions, for the maintenance of the unemployed. They were the dynamic behind the growing pressure on the Liberal Government to introduce bold social legislation.

(8) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (23rd January, 1895)

Last night we had an informal conference with the ILP leaders. Ramsay MacDonald and Frank Smith (who are members both of the Fabians and the ILP) have been for some time harping on the desirability of an understanding between the two societies. To satisfy them Sidney (Webb) arranged a little dinner of Keir Hardie, Tom Mann, Edward Pease and George Bernard Shaw and the two intermediaries. I think the principals on either side felt it would come to nothing. Nevertheless, it was interesting.

Tom Mann said the Progressives on the LCC were not convinced Socialists. No one should get the votes of the ILP who did not pledge himself to the 'Nationalisation of the Means of Production'. Keir Hardie, who impressed me very unfavourably, deliberately chooses this policy as the only one which he can boss. His only chance of leadership lies in the creation of an organisation "against the government"; he knows little and cares less for any constructive thought or action. But with Tom Mann it is different. he is possessed with the idea of a 'church' - of a body of men all professing exactly the same creed and all working in exact uniformity to exactly the same end. No idea which is not 'absolute', which admits of any compromise or qualification, no adhesion which is tempered with doubt, has the slightest attraction to him. And, as Shaw remarked, he is deteriorating. This stumping the country, talking abstractions and raving emotions, is not good for a man's judgment, and the perpetual excitement leads, among other things, to too much whisky.

I do not think the conference ended in any understanding. We made clear our position. We were a purely educational body, we did not seek to become a 'party'. We should continue our policy of inoculation, of giving to each class, to each person, that came under our influence the exact dose of collectivism that they were prepared to assimilate.

(9) Keir Hardie, speech at the Labour Party Conference (February, 1907)

I thought the days of my pioneering were over but of late I have felt, with increasing intensity, the injustice inflicted on women by our present laws. The Party is largely my own child and I cannot part from it lightly, or without pain; but at the same time I cannot sever myself from the principles I hold. If it is necessary for me to separate myself from what has been my life's work, I do so in order to remove the stigma resting upon our wives, mothers and sisters of being accounted unfit for citizenship.

(10) In 1910 James Keir Hardie explained the influence that Christianity had on his political beliefs.

I have said, both in writing and from the platform many times, that the impetus which drove me first into the Labour movement, and the inspiration which has carried me on in it, has been derived more from the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth than from all other sources combined.

(11) Fran Abrams, Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003)

The young student, now aged twenty-four, had fallen for the fifty-year-old politician in a manner which went far beyond mere admiration or friendship. As the relationship developed, the complexity of these feelings became clearer. Sylvia saw Hardie as part political hero, part father-figure and part potential lover. Gradually he began to return her feelings. In the summer of 1906, when Sylvia was forced to leave the Royal College of Art because her grant had been withdrawn, Hardie helped her move into cheaper lodgings, soothed her furrowed brow and took her out for a cheering meal. From then on Sylvia often visited him at the House of Commons and the two walked together in St James's Park or spent the evening at Nevill's Court. Quite how they dealt with the fact that he was already married is not entirely clear. Sylvia later described his relationship with Lillie as "tragic", probably reflecting Hardie's own account. Nor was Sylvia the first woman with whom Hardie had had extramarital relations: in 1893 he had a brief but intense flirtation with Annie Hines, the daughter of a party worker in Oxfordshire.

(12) Keir Hardie, letter to Votes for Women (1st October, 1909)

That there is difference of opinion concerning the tactics of the militant Suffragettes goes without saying, but surely there call be no two opinions concerning the horrible brutality of these proceedings? Women, worn and weak by hunger, are seized upon, held down by brute force, gagged, a tube inserted down their throats and food poured or pumped into the stomach.

(13) Hiliare Belloc, letter to Wilfred Scawen Blunt (18th April, 1911)

What I told you of Keir Hardie is reliable. The man has a larger dose of sincerity than most politicians: he suffers from a very touchy vanity which follows that kind of success, proceeding from such social origins: finally, he is not to be depended upon for active criticism of the Administration, because, in having produced the Labour Party his life's work is done and he is content, and on the side of the contented people in most things. But, as I have said, his love of justice is quite genuine and you will find that he is respected by men who are attached to that attribute.

(14) Keir Hardie issued a statement on the outbreak of the First World War.

The long-threatened European war is now upon us. You have never been consulted about this war. The workers of all countries must strain every nerve to prevent their Governments from committing them to war. Hold vast demonstrations against war, in London and in every industrial centre. There is no time to lose. Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!

(15) Keir Hardie, speech (11th April 1914)

I shall not weary you by repeating the tale of how public opinion has changed during those twenty-one years. But, as an example, I may recall the fact that in those days, and for many years thereafter, it was tenaciously upheld by the public authorities, here and elsewhere, that it was an offence against laws of nature and ruinous to the State for public authorities to provide food for starving children, or independent aid for the aged poor. Even safety regulations in mines and factories were taboo. They interfered with the ‘freedom of the individual’. As for such proposals as an eight-hour day, a minimum wage, the right to work, and municipal houses, any serious mention of such classed a man as a fool.

These cruel, heartless dogmas, backed up by quotations from Jeremy Bentham, Malthus, and Herbert Spencer, and by a bogus interpretation of Darwin’s theory of evolution, were accepted as part of the unalterable laws of nature, sacred and inviolable, and were maintained by statesmen, town councillors, ministers of the Gospel, and, strangest of all, by the bulk of Trade Union leaders. That was the political, social and religious element in which our Party saw the light. There was much bitter fighting in those days. Even municipal contests evoked the wildest passions.And if today there is a kindlier social atmosphere it is mainly because of twenty-one years’ work of the ILP.

Scientists are constantly revealing the hidden powers of nature. By the aid of the X-rays we can now see through rocks and stones; the discovery of radium has revealed a great force which is already healing disease and will one day drive machinery; Marconi, with his wireless system of telegraphy and now of telephony, enables us to speak and send messages for thousands of miles through space.Another discoverer, through means of the same invisible medium, can blow up ships, arsenals, and forts at a distance of eight miles.

But though these powers and forces are only now being revealed, they have existed since before the foundation of the world. The scientists, by sympathetic study and laborious toil, have brought them within our ken. And so, in like manner, our Socialist propaganda is revealing hidden and hitherto undreamed of powers and forces in human nature.

Think of the thousands of men and women who, during the past twenty-one years, have toiled unceasingly for the good of the race. The results are already being seen on every hand, alike in legislation and administration. And who shall estimate or put a limit to the forces and powers which yet lie concealed in human nature?

Frozen and hemmed in by a cold, callous greed, the warming influence of Socialism is beginning to liberate them. We see it in the growing altruism of Trade Unionism. We see it, perhaps, most of all in the awakening of women. Who that has ever known woman as mother or wife has not felt the dormant powers which, under the emotions of life, or at the stern call of duty are even now momentarily revealed? And who is there who can even dimly forecast the powers that lie latent in the patient drudging woman, which a freer life would bring forth? Woman, even more than the working class, is the great unknown quantity of the race.

Already we see how their emergence into politics is affecting the prospects of men. Their agitation has produced a state of affairs in which even Radicals are afraid to give more votes to men, since they cannot do so without also enfranchising women. Henceforward we must march forward as comrades in the great struggle for human freedom.

The Independent Labour Party has pioneered progress in this country, is breaking down sex barriers and class barriers, is giving a lead to the great women’s movement as well as to the great working-class movement. We are here beginning the twenty-second year of our existence. The past twenty-one years have been years of continuous progress, but we are only at the beginning. The emancipation of the worker has still to be achieved and just as the ILP in the past has given a good, straight lead, so shall the ILP in the future, through good report and through ill, pursue the even tenor of its way, until the sunshine of Socialism and human freedom break forth upon our land.

(16) Isabella Ford, The Labour Leader (30th September, 1915)

His extraordinary sympathy with the women's movement, his complete understanding of what it stands for, were what first made me understand the finest side of his character. In the days when Labour men neglected and slighted the women's cause or ridiculed it, Hardie never once failed us, never once faltered in his work for us. We women can never forget what we owe him.

(17) Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement (1931)

I knew that Keir Hardie had been failing in health since the early days of the war. The great slaughter, the rending of the bonds of international fraternity, on which he had built his hopes, had broken him. Quite early he had a stroke in the House of Commons after some conflict with the jingoes. When he left London for the last time he had told me quietly that his active life was ended, and that this was forever farewell, for he would never return. In his careful way he arranged for the disposal of his books and furniture and gave up his rooms, foreseeing his end, and fronting it without flinching or regret.

(18) The Women's Dreadnought (2nd October, 1915)

Keir Hardie has been the greatest human being of our time. When the dust raised by opposition to the pioneer has settled down, this will be known by all.

The first Labour Member of Parliament, he was for years absolutely alone. He held to his independence, untouched by the temptations that assault lesser men. One of the outstanding features of his years of absolute isolation as the sole Labour Member was his fight for the unemployed. For his contention that workless men and women have a claim upon society to be provided with work, he was ridiculed and most angrily abused. But by the poor and those who understood him he was greatly loved.

He toiled to awaken the members of the Parliamentary Labour Party, and the Labour movement as a whole, to the great need for the enfranchisement of women, and for the comradeship of working women and working men. He scarcely made a speech without dwelling upon this, and when enthusiasts asked him to write a motto, he would choose "Votes for Women and Socialism for All".

(19) Bruce Glasier, diary entry on the funeral of James Keir Hardie (September, 1915)

A considerable crowd of people - mostly ILP friends (workmen chiefly, snatching a few moments from their dinner hour). The Chapel was packed. The Rev. Forson read the service. Jowett says a few words, not very impressive. Then Forson gave his eulogy. A ghastly malapropos one. All about Hardie's early connection with the Evangelical Union church - no reference to his political work, internationalism or peace. Hardie might have been a grocer. It made me wild. Then when Forson ended and there was silence, and I saw our old hero was about to be lowered out of sight, I stood forward and laying my hands on the bier said a few confused words about his being the greatest agitator of his day and asking comrades to pledge themselves to work for his beloved ILP, for internationalism and peace, the coffin disappearing as I spoke.

(20) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs: 1869-1924 (1937)

Hardie died of a broken heart. He had always been a pacifist, and had fiercely opposed the South African War, being nearly killed in Glasgow during a riot caused by one of his speeches there against it. Between the end of the South African War and 1914 he burned himself out working to try and prepare a tremendous international general strike, to be declared when the European War, which he could see was coming, broke out. This strike he hoped would paralyze hostilities and bring immediate peace.

When August, 1914, showed him that his hopes were vain, that the workers' leaders he had painfully taught were marching to war and singing their respective patriotic songs, and when British Labour refused to inaugurate a great strike on behalf of peace, Hardie became a broken man. For the next twelve months the old dominant figure we had known was seen no more in the corridors of the House of Commons; he shrank into a travesty of his former self, never spoke in debates and said little to anyone. The great leader of Labour was dying on his feet. We all loved and respected him; it was a great grief to us that our attitude to war was driving the sword into his heart; but between our conscience and our friend there was only one choice.

(21) Kenneth O. Morgan, Keir Hardie (19th September, 2008)

Keir Hardie is Labour's greatest pioneer and its greatest hero. Without him, the party would never have existed. Without him, Attlee, Bevan and Castle would never have become cabinet ministers. This extraordinary man rose from the pits of Ayrshire to change the world. He became the first Labour MP, the founder of the ILP, first leader of the Labour party, pioneer editor of the Labour Leader, and a giant in the socialist movement worldwide. Miraculously, he created a new party, as "an uprising of the working class".

Hardie was both our greatest strategist and our greatest prophet and evangelist. His vision made the Labour Alliance. He saw that a mass party needed a mass working-class base, the unions from which he himself had sprung. But his ILP also brought in middle-class socialists. Labour should "blend the classes into one human family", but always, independently, "work out its own emancipation".

And he was a unique popular crusader. In Cambridge in 1907 the young Hugh Dalton was deeply moved by Hardie's "total lack of fear or anger"; he became a socialist that night. No one more powerfully exposed the cruelties of late-Victorian capitalists like Lord Overtoun's "white slavery". Yet Hardie insisted that socialism "made war upon a system not a class". Labour should "capture power, not destroy it".

Hardie attached his party to great issues and values still relevant today. He was the greatest-ever male feminist. Through his friendship with Sylvia Pankhurst, he insisted that women's liberation involved women not just as voters, but as mothers, workers, human beings. He crusaded passionately against poverty: his proud description was "member for the unemployed", campaigning for the minimum wage and eliminating child poverty. He pioneered social welfare, advocating a national health service financed from redistributive taxation, not a poll tax. He was a principled democrat. His socialism was not a massive state bureaucracy but the true republican democracy of Milton, including Welsh and Scottish devolution.

His global vision linked Labour with colonial freedom. In Bengal in 1907 he outraged the Raj by demanding that India should actually be governed by Indians. I once saw a walking stick in Hardie's Cumnock home, a present from his great admirer, Mahatma Gandhi. In South Africa, Hardie almost uniquely argued that self-government there was for whites only and that in Natal and Cape Colony black Africans' status would seriously erode. And finally, Hardie anchored Britain in the international socialist movement. He was, like Wordsworth in 1789, a citizen of the world. He crusaded with French comrades for international peace. He stood up courageously during the Boer war, denouncing its "methods of barbarism". In 1914, he was horrified by that imperialist bloodbath, and it killed him. As George Bernard Shaw movingly wrote, Hardie's indomitable truth would still go marching on.

Hardie's greatness is reflected in the simplicity of his lifestyle. You could never imagine him, like Attlee, counting up the number of Etonians in his government nor, like Bevan, quaffing Bollinger with Beaverbrook. Bruce Glasier wrote of Hardie that "the man and his gospel were indivisible". His simple heroism made our party and our world.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)