Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

Emmeline Pethick, the daughter of Henry Pethick, a businessman in Bristol, was born in Clifton on 21st October 1867. She later recalled: "My mother bore thirteen children, of whom five died in infancy. My youngest brother was born seventeen years after me. Those were the days of large families. I never heard my mother make any complaint about this excessive childbearing. She accepted it with complete surrender and even with satisfaction."

Henry Pethick was a devout Methodist. "As children we were all taken to Church as soon as we could walk and we had to sit very still indeed, because if not, we would be slapped afterwards. When we were older we had to remember and repeat the text at dinner-time, and if we failed to do this we were set to learn pieces of Scripture by heart."

Emmeline was sent away to boarding school in Devizes at the age of eight. A rebellious child, she was constantly in trouble with her teachers. After being transferred to a Quaker school she was accused of being "a corrupting influence on other children". Her biographer, Brian Harrison has argued: "Her lifelong instinctive sympathy with children was striking... She portrayed herself later as a truthful and rational child, but to adults she must have seemed wilful and stubborn."

In 1891 Emmeline became a voluntary social worker at the West London Methodist Mission. Emmeline helped organise a club for young working-class girls. Emmeline was shocked by the poverty she encountered and it was during this time she was converted to socialism. Emmeline believed it was important to give these girls a practical example of socialism in action. In 1895 Emmeline joined with Mary Neal to form the Esperance Club that was influenced by the ideas of William Morris, Edward Carpenter, and Walt Whitman. This involved helping a group of young women establish a co-operative dressmaking business.

In 1899 Emmeline met the wealthy lawyer, Frederick Lawrence. The couple fell in love but Emmeline refused to marry Frederick because he did not share her socialist beliefs. In 1900 she developed a hostel at Littlehampton for working girls' holidays. It was not until 1901, when Frederick had been converted to socialism, that Emmeline agreed to marry him. Frederick agreed to adopt Pethick-Lawrence as their joint name. Brian Harrison has pointed out: "It was the start of an unusual lifelong partnership in which each annexed the surname of the other, while each retained separate bank accounts and considerable autonomy within a marriage whose harmony was much advertised and celebrated."

Soon after her marriage Emmeline thought she was pregnant. Frederick wrote that the birth "will make us both extra happy". He added: "Isn't it splendid dear. My heart just singing and singing and won't keep quiet." However, Emmeline suffered a miscarriage and received news that she could not have children. Frederick wrote to her: "I am to you a splendid husband and you to me a splendid wife and it is enough!"

In 1901 Frederick Pethick-Lawrence became the owner of The Echo, a left-wing evening newspaper. He recruited friends from the socialist movement such as Ramsay MacDonald and H. N. Brailsford to write for the newspaper. Frederick also published and edited the monthly, Labour Record and Review (1905-07). Emmeline later argued: "His outstanding qualities of intellect, balanced judgment and practical administration in business and finance became the rock upon which I have built, since then, the structure of my life."

For the next four years Emmeline spent her time helping the Independent Labour Party and developing her ideas with the Esperance Club. However, when Emmeline read about the arrest and imprisonment of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney in October 1905, she decided to take an interest in the suffrage movement. The following year she met Kenney and after a long discussion with her she decided to join the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

A few months after joining the WSPU Emmeline was arrested while trying to make a speech in the lobby of the House of Commons. Emmeline was sent to prison, the first of six terms of imprisonment that she served for her political activities. She later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "When the morning newspaper brought the unexpected news of my first arrest in the Suffrage Movement, my father reacted to it in precisely the same way as I should have reacted had our positions been reversed. He was proud that a child of his hand not hesitated to make a stand for the extension of democratic liberty."

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence also became involved in the struggle for the franchise. In 1907 Frederick and Emmeline started the journal Votes for Women. The Pethick-Lawrence's large home in London also became the office of the WSPU. It was also used as a kind of hospital where women made ill by their prison experiences could recover their strength before embarking on further militant acts. The couple also contributed more than £6000 to the funds of WSPU.

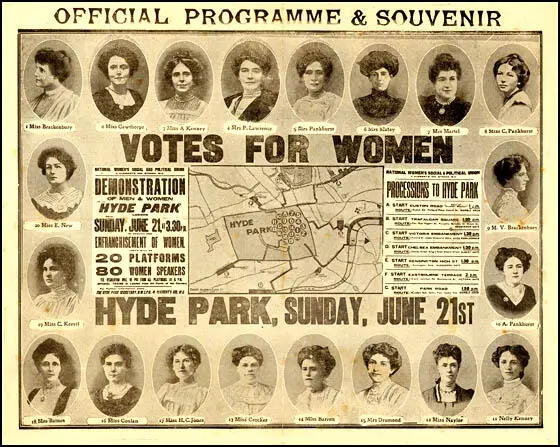

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence had disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored her objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

Both Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence went on hunger strike and had to face the full rigours of forcible feeding twice a day for several days. He later recalled the experience in his memoirs, Fate Has Been Kind (1943): "The head doctor, a most sensitive man, was visibly distressed by what he had to do. It certainly was an unpleasant and painful process and a sufficient number of warders had to be called in to prevent my moving while a rubber tube was pushed up my nostril and down into my throat and liquid was poured through it into my stomach. Twice a day thereafter one of the doctors fed me in this way. I was not allowed to leave my cell in the hospital and for the most part I had to stay in bed. There was nothing to do but to read; and the days were very long and went very slowly."

Christabel Pankhurst later recorded: "Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed."

After Emmeline and Frederick were released from prison they began to speak openly about the possibility that this window-smashing campaign would lose support for the WSPU. At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline and Frederick about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) wrote: "Even the split with the WSPU did not end of this agony - the Pethick-Lawrences were still facing bankruptcy proceedings. An auction of their belongings was held at The Mascot, but raised only £300 towards their £1,100 court costs even though many friends arrived to buy personal possessions and give them back to the couple. Even the auctioneer returned to them a trinket he had bought as a keepsake. The rest of the costs were later taken from Fred's estate, plus a further £5,000 for repairs to shop windows damaged in the raids. Fortunately he had deep pockets and did not have to sell his home."

Pethick-Lawrence continued to work for the suffrage cause and spent most of her energies after 1912 writing for her journal, Votes for Women. She also joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Other members included Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard.

During the First World War Emmeline was a prominent member of the Women's International League for Peace. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence stood as Labour candidate for Rusholme. As Brian Harrison pointed out: "she championing nationalization, a capital levy, equal pay, and an equal moral standard, but she came bottom of the poll with only a sixth of the votes cast."

In the 1920s and 1930s Emmeline worked for the Women's International League, an organisation committed to world peace. Emmeline also became involved in the campaign led by Marie Stopes to provide birth-control information to working class women. From 1926 to 1935 was president of the Women's Freedom League.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence published her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World, in 1938. The book is dedicated to her husband, "my unchanging comrade and my best friend". One critic argued: "Though impressively fair-minded and at times perceptive, her account of the suffragettes is essentially an uncritical and largely impersonal chronology. Nowhere did she convincingly justify the contradiction between her humanitarian and democratic instincts on the one hand, and her promotion of violent tactics and authoritarian suffrage structures on the other."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence remained active in politics until 1950 when she had a serious accident that left her immobilized. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence looked after Emmeline until she died of a heart attack at her home at Gomshall, Surrey, on 11th March 1954. He wrote to a friend: "I feel a bit dazed. It is as though I was at a violin concerto with the violinist absent."

YouTube Videos

Primary Sources

(1) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote about her childhood in her book My Part in a Changing World.

My mother bore thirteen children, of whom five died in infancy. My youngest brother was born seventeen years after me. Those were the days of large families. I never heard my mother make any complaint about this excessive childbearing. She accepted it with complete surrender and even with satisfaction.

As children we were all taken to Church as soon as we could walk and we had to sit very still indeed, because if not, we would be slapped afterwards. When we were older we had to remember and repeat the text at dinner-time, and if we failed to do this we were set to learn pieces of Scripture by heart

(2) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, My Part in a Changing World (1938)

My father is still part of me still. He imparted to me so much of his own nature that as long as his blood is still flowing in my veins, I feel he is still alive. He was a born rebel… The closest bond between my father and me was his passionate love of justice, which I inherited from him. So long as there existed within the realm of his personal knowledge any wronged individual my father could not rest inactive. My mother thought he went too far; and perhaps he did… He was often in the bad books of people in authority who believed in the status quo, and wanted peace at any price.

When the morning newspaper brought the unexpected news of my first arrest in the Suffrage Movement, my father reacted to it in precisely the same way as I should have reacted had our positions been reversed. He was proud that a child of his hand not hesitated to make a stand for the extension of democratic liberty. Later that morning he was met by one of his colleagues on the Bench with expressions of sympathy. "Sympathy, my dear fellow," he replied, "I don't need sympathy. Give me your congratulations! I'm the proudest man in England!'

(3) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote about her education in her book My Part in a Changing World.

The idea of the higher education had not, when I was young, reached as far as our small seaside town. I never knew of any girl in Weston-Super-Mare who aspired to go to College or University… It was my mother's wish that I should be sent, when fifteen years of age, for a year or two to what in those days was called a "Finishing School". She thought that my manners and my deportment needed polishing up, as no doubt they did.

(4) In 1891 Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence began work as a social worker in a working-class area of London.

Drunkenness was extremely common… It seemed for many the only refuge from depression and misery. The effect of drunkenness upon the ordinary relationship of husband and wife, parents and children, was disastrous. There was a woman whose husband used to knock her about badly when in drink. But he went to the Mission Hall in the district, was converted and signed the pledge. All went well for some time until she again turned up with several bruises. "Oh, Mrs. Smith, has your husband taken to drink again?" She replied: "Oh, no, that was another lady what done that! Since my husband went to the Misson Hall, he ain't like a husband at all - he is more like a friend!"

There was a particular point of view with regard to wife-beating. A friend of mine was once walking along the street and she passed a woman with a black eye. At the same time two other women passed, and one of them remarked: "Well, all I can say is, she is a lucky woman to have a husband to take that trouble with her." Another woman who had gone through a similar experience remarked: "Well, it ain't pleasant to be knocked about, but the making-up is lovely."

(5) In his book, Fate Has Been Kind, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence explained the role he played in the WSPU.

That autumn (1906) saw, the beginning of the Monday afternoon 'At Homes', which went on continuously year in year out during the militant campaign. They were intended principally for women, but men were not excluded. Strategy was explained, militant demonstrations were announced, a collection was taken and members were enrolled. I generally came and sold literature - books, pamphlets and, later, the Votes for Women newspaper. When the attendance grew too big to be accounted in the office in Clement's Inn the venue was changed to the Portman Rooms in Baker Street, and later to the Queen's Hall.

At the end of October 1906 events occured which brought me into far closer association with the movement. My wife was arrested. She had gone, with other members of the Women's Social and Political Union to the House of Commons on the day that Parliament opened; and in accordance with a preconcerted plan she had jumped up on to one of the seats in the Central Lobby and started to address the M.P.s and others who were present. Pulled down and bundled out into the street, along with a number of other women who had made a similar protest, she had tried to re-enter the House and had been taken into custody.

I went with her to the Court next morning, and she surrendered to her bail, together with nine other women, including Mrs. Cobden Sanderson, daughter of Richard Cobden. The magistrate bound them all over to enter into their own recognizances to keep the peace for six months. This they unanimously refused to do. In default, they were committed to prison for two months. They were accordingly packed off the Holloway.

I determined at once that during my wife's absence her side of the work should not suffer. I agreed to look after the finances, and at a public meeting that very afternoon I made an appeal for funds. By way of setting the ball rolling I promised to contribute £10 for every day of her imprisonment.

(6) Miss A. Meechan, letter to the Public Prosecutor (March 1907)

May I respectfully ask if it is not possible to break up the Suffragette movement by taking action against Mr and Mrs Pethick Lawrence for conspiring and inciting to serious breaches of the peace. It can very easily be proved that Mr Pethick Lawrence went to East Ham on one occasion and hired a number of women at two shillings per day plus their expenses. These women were drilled into their work by Mr Lawrence and his assistants and took part in very disorderly scenes... These women (and many of the women agitators who are paid £2-£5 per week) know nothing of politics or Votes for Women questions and are paid for creating disturbance at command of the leaders.

(7) In her book My Part in a Changing World, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence described how the police were sometimes violent towards the women suffragists.

Police had been drafted in from the East End of London. They knew nothing about the suffrage agitation and were accustomed to dealing with drunks and roughs. Also large and well-nourished bullies had been imported into the district. They may have been police in plain clothes. An order had evidently been given that the police were not to arrest; the alternative was a six-hours' battle between unarmed women who attempted to stand their ground, and police who fought with methods of torture. Women were lifted and thrown to the ground and kicked - they were deliberately beaten on the breasts and were subjected to such terrible violence that a short time afterwards two of them, Mrs. Mary Clarke and Miss Henria Williams, died suddenly from heart attacks. Fifty women were laid up with the injuries they had received… Dr. Jessie Murray collected evidence regarding the methods of violence used… This evidence was classified under: (1) Unnecessary violence. (2) Methods of torture, i.e. bending thumbs backwards, twisting arms, pinching, gripping the throat and forcing back the head with violence, forcing fingers up nostrils, and so on. (3) Acts of indecency.

(8) In her book My Part in a Changing World, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that groups of young men often tried to disrupt suffrage meetings.

It was mainly from young men, and often entirely from students, that opposition came… We had one meeting in the Town Hall in Birmingham. University students came en masse in order to prevent the audience from hearing the speakers. They kept up a stampede for over an hour, stamping, yelling and singing. Christabel stood on the platform apparently amused at their antics, and every now and then addressed the youths as if they were children, while she turned her main attention to the reporters, who thronged the press table, and was able to get her whole speech over to them. A box of mice was emptied on the table beside her. She took them gently into her hand and let them run up and down her bare arms and spoke to the thoughtless boys of the cruelty of frightening small and helpless creatures for the sake of fun.

(9) On 14th October 1908, Constance Lytton met Mrs. Pethick Lawrence in London. That night Constance wrote a letter to her mother.

I went to the Suffragette Office to see Mrs. Lawrence and to congratulate her on the meeting of the day before, inquire the latest news, and finally say: "You know my reservations as to some of your methods, but my sympathies are much more with you than with any of your opponents… I want to be of use if I can. Is there anything I can possibly do to help you?" A good deal of talk ensued. She said, "Yes," I could help them. Could I see to it that Herbert Gladstone was asked to treat the Suffragettes as political offenders, which they are, and not as common criminals, which they are not?

(10) In her book Unshackled, Christabel Pankhurst described the situation in March 1912.

Eighty-one women were still in prison, some for terms of six months… Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed.

(11) In her book, Unshackled, Christabel Pankhust explained the reasons why Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence left the WSPU.

On the return from Canada of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence there was a consultation in France. The outcome of this and a further meeting was the serious announcement that they and we had parted company owing to a difference of opinion as to the policy of the WSPU. This separation on a matter of policy was a cause of deep regret to all concerned.

(12) In her book My Part in a Changing World, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence described how she was expelled from the WSPU.

Christabel Pankhurst was in Paris… as soon as Emmeline could travel she joined her in Paris. They asked us (Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence) to come to Boulogne to confer with them. Mrs. Pankhurst met us with the announcement that she and Christabel had determined upon a new kind of campaign. Henceforward she said there was to be a widespread attack upon public and private property… This project came as a shock to us both. We considered it sheer madness to throw away the immense publicity and propaganda value of our present policy… They were wrong in supposing that a more revolutionary form of militancy, which attacks directed more and more on the property of individuals, would strengthen the movement and bring it to more speedy victory.

Emmeline Pankhurst agreed with Christabel… Excitement, drama and danger were the conditions in which her temperament found full scope. She had the qualities of a leader on the battlefield… The idea of a 'civil war' which Mrs. Pankhurst outlined in Boulogne and declared a few months later was repellent to me.

When we arrived back in London we were met by a friend. Instead of the smiles that we expected, sadness was written upon her face… "Is anything the matter? What is it?" I demanded. "They are going to turn you out of the Women's Social and Political Union."

My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us.

(13) On 18th October 1912 the WSPU issued a statement.

Mrs. Pankhurst and Miss Christabel Pankhurst outlined a new militant policy which Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence found themselves altogether unable to approve. Mrs. Pankhurst and Miss Christabel… recommended that Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence should… leave the Women's Social and Political Union.

(14) Fran Abrams, Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003)

Even the split with the WSPU did not end of this agony - the Pethick-Lawrences were still facing bankruptcy proceedings. An auction of their belongings was held at The Mascot, but raised only £300 towards their £1,100 court costs even though many friends arrived to buy personal possessions and give them back to the couple. Even the auctioneer returned to them a trinket he had bought as a keepsake. The rest of the costs were later taken from Fred's estate, plus a further £5,000 for repairs to shop windows damaged in the raids. Fortunately he had deep pockets and did not have to sell his home.

(15) In his book Fate Has Been Kind (1942), Frederick Pethick-Lawrence explained his reaction to the expulsion

Mrs. Pankhurst invited us to her room. She then told us that she had decided to sever our connection with the WSPU. We saw, then, that the breach between ourselves and the Pankhursts was complete and irrevocable. There was, further, no appeal against our exclusion from the WSPU. Mrs. Pankhurst was the acknowledged autocrat of the Union. We had ourselves supported her in acquiring this position several years previously; we could not dispute it now.