Women's Freedom League

In 1907 some leading members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Clare Mordan and Mary Blathwayt were having too much influence over the organisation. (1)

In a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference. As Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence pointed out: "She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people. Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to democracy, and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own." (2)

Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst sent out a letter to all branches of the WSPU stating that this was not in any way a democratic group. "We are not playing experiments with representative government. We are not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are a militant movement... It is not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are militant movement... It is after all a voluntary militant movement: those who cannot follow the general must drop out of the ranks." As Simon Webb has pointed out: "This is quite unambiguous. Members must not expect to influence policy or question the leader, the role is limited to obeying orders." (3)

Women's Freedom League

As a result of this speech, Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Katherine Vulliamy, Helen Fox, Muriel Matters, Octavia Lewin, Emma Sproson, Margaret Nevinson, Henria Williams, Constance Tite, Violet Tillard, Emily Duval and about sixty-five other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL) in November 1907. Most of its members were socialists who wanted to work closely with the Labour Party who "regarded it as hypocritical for a movement for women's democracy to deny democracy to its own members." (4) Christabel Pankhurst attempted to play down the conflict. She stated, "please don't call it a split there has been no particular row... it is more of a parting of company." (5)

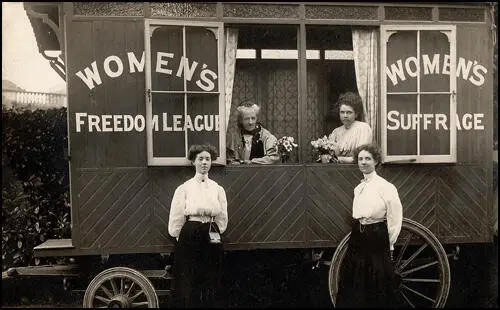

Irene Tillard and Violet Tillard standing in front of the caravan.

Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig and Edith How-Martyn were all members of the Independent Labour Party. However, they distrusted the other political parties who had for so long blocked attempts to extend the franchise to women. Therefore they wanted "a women's suffrage organisation independent of the political parties; an organisation run and controlled by women which would prioritise women's suffrage above all else; a campaign which would be intense and militant, and which would not end until women had achieved their demands - equal suffrage on the same terms as men." (6)

Charlotte Despard became the dominant member of the Women's Freedom League. According to Stella Newsome : "Mrs Despard's struggles for social reform convinced her of the need for women's enfranchisement and she joined the suffrage movement in the early days of this century. In 1906 she was working in the militant movement. Believing firmly that women who were demanding self-government from the State should have self-government in their own organisation she became founder of the Women's Freedom League. As first President of the League she shirked nothing – the difficulties of finance, of organisation, of propaganda were difficulties to be overcome. At any meeting, indoors or outdoors, large or small, she gave of her best." (7)

Violet Tillard became Assistant Organising Secretary of the organisation. She was active in promoting women's suffrage in newspapers. In one letter she pointed out the difference between the Women's Freedom League and the Women Social & Political Union. "The Women's Freedom League differs from the Women's Social and Political Union chiefly in the internal organisation, which in democratic; and in the fact that it is not part of its policy at present to interrupt Cabinet Ministers at meetings; but the societies at one in their aim the removal of the sex disability, and in their policy of opposing the Government at by-elections." (8)

The Women's Freedom League "had formed at least sixty branches by 1909, with a constant membership in these of no more than 5,000 women, although given the tendency for League branches to disband and reform, and for new branches to emerge, the number of women who at one stage were members of the League was much greater." (9) In a letter to The Times the WFL Hon. Secretary, Edith How-Martyn wrote that they had sixty-five local branches, with a total membership of "about 5,000... it must be remembered that we have a large body of sympathizers who will not become members because they cannot fulfil the very stringent regulations." (10)

Teresa Billington-Greig became chairman of the WFL Executive Committee and National Honorary Organising Secretary. "I presided at both the conferences of the WFL which decided its future and at those that followed annually until 1911. This was by the express wish of Mrs Despard, who felt that the conduct of big business meetings was not the job for her... The queen-pin of our movement was of course Edith How-Martyn, who, as Honorary Secretary, carried the heaviest burden with a spirit which never faltered and won admiration from us all." (11)

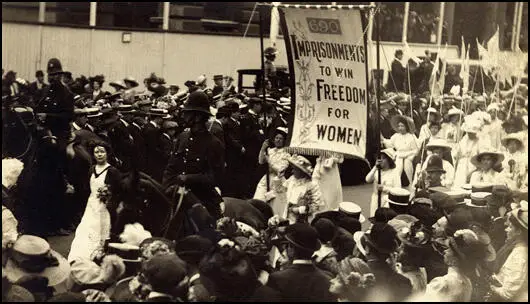

Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. Court protests against the trial of women "by man made laws", a favourite idea of Teresa Billington-Greig, were carried out by the WFL. (12)

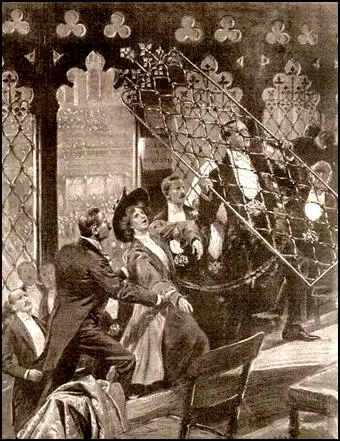

Ladies' Gallery Demonstation

On 28th October 1908 Helen Fox and Muriel Matters organised a Women's Freedom League demonstration that would gain the maximum publicity. According to Margaret Nevinson, "an extra dull debate was going on when suddenly the bored audience was electrified at hearing a woman's voice, clear and very earnest, from the gilded cage, calling upon the Legislature to give justice and freedom to women." (13)

Officials rushed up the stairs to the Ladies' Gallery of the House of Commons, then enclosed from the rest of the chamber by a brass grille. Both women had chained themselves to the grille. Helen Fox delivered a speech she had prepared on the rights of women. Meanwhile the two-foot banner had descended on the end of the rope supports to within a few feet of the reporters' tables, where it flaunted itself in the faces of the Commons with the announcement that the 'Women's Freedom League demands votes for women this session.' (14)

When officials made attempts to remove them, it was discovered that they had chained and padlocked themselves to the grille in such a way that in order to remove them the grille would have to be removed as well. It took officials over ten minutes to wrest the grille from its supports. Once this was done "portions of the grille, which were carried behind the women to a committee room for the chains to be filed off." (15)

It has been argued that "While attached to the grille Matters, by a legal technicality, was judged to be on the floor of Parliament and thus, the words spoken by her that day are still considered to be the first delivered by a woman in the House of Commons." (16) The two women sat in a committee room until a locksmith was found to separate them from the thirty-foot long grille. (17)

Muriel Matters then went round to join the demonstration taking place in front of Parliament. They were shouting "votes for women" and yelling "Down with Liberal hypocrites" and Call yourself a Liberal". (18) Fifteen arrests were made including Muriel Matters, Violet Tillard, Alison Neilans, Arnold Cutler, Edith Bremer, Emily Duval, Margaret Henderson, Marion Leighfield. Matters was charged with disorderly conduct and after being found guilty she was sent to Holloway Prison for a month. After her release she adopted the cause of prison reform. (19)

Growth of Women's Freedom League

On 17 February 1909, the day the House of Commons returned from recess, Muriel Matters hired a pilot and an airship, which she had painted with the words "Votes for Women" in gigantic lettering. (20) Armed with 56lb of Women's Freedom League pamphlets she flew from the Welsh Harp, Hendon, at heights of up to 3500 feet, with the intention of flying over Parliament.The weather conditions and a poor motor meant that Muriel didn't make it to Westminster, but she did fly over outer London for one and a half hours scattering leaflets as she went. Her exploit was a success as it created publicity for the suffrage movement generating headlines in newspapers around the world. (21)

Violet Tillard Assistant Organising Secretary of the WFL helped establish branches of the League on a caravan tour of the south-east counties of England. Tillard also established WFL branches in Ipswich, Carmarthen and Cardiff. In November, 1908, the caravan visited visited Sussex. On 28th November, Tillard spoke at a meeting at Upminster addressed by Alice Schofield and Henria Williams. (22)

at Upminster with Alice Schofield and Violet Tillard (28th November 1908)

Muriel Matters had arrived from Australia in 1905. She lived in a colony had gained attention for being the first self-governing territory to give women equal franchise on the same terms as it was granted to men. She was one of the more creative members of the Women's Freedom League. In February 1909, Muriel Matters gained further notoriety when she travelled across London in a hot air balloon, dropping suffrage literature on the unsuspecting population! (23)

1909 Bermonsey By-Election

On 28 October 1909 there was a by-election in Bermondsey. A supporter of women's suffrage, Alfred Salter was standing for the Labour Party. However, the Liberal Party had won the seat in the 1906 General Election and after forming the government had refused to give women the vote. Alison Neilans and Alice Chapin of the Women's Freedom League decided to try and invalidate the election. Neilans later recalled that this action "had been running in the minds of members of the League for nearly two years." Chapin added: "The battle of votes for women was one that was going to be fought out to the finish. It was perfectly logical for them to protest at elections and say they would not put up with the tyranny of the present Government." (24)

On the day of the election, Neilans and Chapin attacked polling stations, smashing bottles containing corrosive liquid over ballot boxes, in an attempt to destroy votes. According to a report in the The New York Times, Chapin "broke a bottle of champagne containing corrosive acid on a ballot box with the apparent intention of destroying the ballots which the box contained. The acid, little or none of which found its way into the box, spattered upon election officials, one of whom were badly burned." (25)

The Times claimed that the presiding officer, George Thornley, was blinded in one eye in one of these attacks, and a Liberal agent suffered a severe burn to the neck. The count was delayed while ballot papers were carefully examined, 83 ballot papers were damaged but legible but two ballot papers became undecipherable. Despite the actions of the two women it was decided the election was valid. (26)

Alison Neilans defended her action by claiming: "There had been a great shriek in the Press and elsewhere about vitriol, which was as unjust as it was ridiculous. The tube she carried contained nothing more dangerous than photographic chemicals, which could do no more damage than produce a black stain. The Women's Freedom League never had intended to injure individuals and never would intentionally. The women identified with this movement had never failed yet in anything they had tried to do, and they would not be foiled in the future. They had among them members of the League who were prepared if necessary to do 10 or 15 years in prison for the good of the cause." (27)

At Capin's trial at the Old Bailey, the injured presiding officer, George Thorley, said Chapin raised her band and brought it smartly down on the mouth of the ballot-box. There was a slight crash as of breaking glass, and witness felt the splash on his face and in his eye. He went to Guy's Hospital. His sight, which has been affected, was improving. He added that he "did not believe for a moment that defendant meant to injure his eye". (28)

Alice Chapin was sentenced to seven months' imprisonment. Three months of her punishment being for interfering with a ballot box, and the rest of the term for assault on a polling clerk. Alison Neilans, "who made a similar attempt to express suffragette sentiments at the by-election, but with less serious consequences, was also convicted and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment." (29)

Neilans went on hunger-strike and was forced-fed. "When the doctors entered her cell they had given her the choice of weapons - nasal tube, stomach tube, or feeding-cup. Which did she prefer? Although she heard the stomach-tube operation was the most dangerous, she choose this method in preference to the nasal feeding. She was held down in the chair by two women, their fingers were forced between her teeth, her head thrown back, the tube was gradually forced down her throat, and the feeding commenced. Although she did not go so far as to describe the operation as torture, she did say it was the most unspeakable outrage that could be offered to anyone." (30)

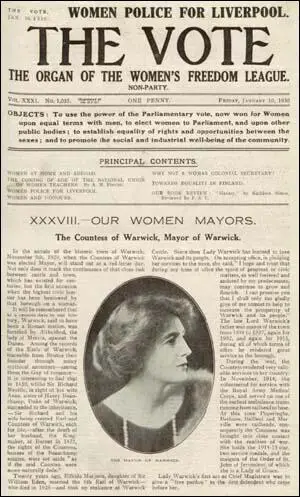

The Vote Newspaper

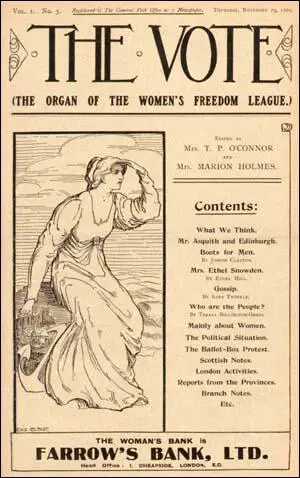

The Women's Freedom League established its own newspaper, The Vote. The first edition, published on 8th September 1909, consisted of four pages. Two months later it had grown to eight pages. (31) The newspaper pointed out: "We hope and believe that through its pages the public will come to understand what the Parliamentary Franchise means to us women. Now it will be both a symbol of citizenship and the key to a door opening out on such service to the community as we have never yet been allowed to render, and therefore it is our earnest hope that our paper will keep its place in the hearts of men and women long after the first victory has been won." (32)

Two of the Women's Freedom League leaders, Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Despard, and were both talented writers and were the main people responsible for producing the newspaper. Louisa Thomson-Price was an experienced journalist and became consultant editor. She also became director of its publishing company, Minerva Publishing. (33) One of Britain's leading writers, Cicely Hamilton, became the first editor of the newspaper. (34)

Louisa Thomson-Price became an important figure in the Women's Freedom League. It was pointed out that she had "boundless energy, an unshaken belief in humanity, a great optimism, a profound knowledge of the questions of the day, and a rare intuition with regard to the "chosen people and the chosen causes" are perhaps the most distinguishing characteristics of the most delightful of colleagues." (35)

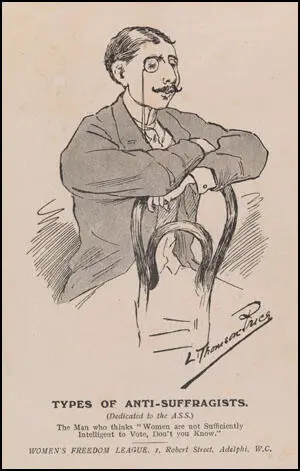

On 4th November, 1909, The Vote carried its first cartoon. It was drawn by Louisa Thomson-Price. Three weeks later, in the issue of 25 November, she contributed the first of a series of twelve cartoons, depicting various stereotypical"Anti-Suffragists", that ran until March 1910. The WFL then issued these cartoons as black and white postcards. The 16th December, 1909, issue, contained a cartoon by Louisa Thomson-Price of H. H. Asquith pulling a "Votes for Women" plum out of his "General Election pie". This image was produced as a WFL poster for use in the January 1910 General Election Election. (36)

The Vote never rivalled either The Common Cause or Votes for Women, but members of the WFL did recognise the importance of their own paper in keeping members informed and in generating a sense of a united organisation. It also used it to explain the philosophy of the group: "We must rebel, we must not rest until the ballot box is no longer the symbol of sex tyranny but the symbol of political sex equality." (37)

As Edith How-Martyn explained: "We cannot reiterate too often that our object is to give a practical example of the impasse which would be produced in our national life if women seriously began to refuse their consent to the autocratic government by men. Passive resistance against unjust authority is binding on those who believe in doing something to win their freedom. Until women win representation they are morally justified in demonstrating that their exclusion from citizenship certainly does involve national injury." (38)

Women's Tax Resistance League

Dora Montefiore was the first person who refused to pay her taxes until women were granted the vote. Outside her home she placed a banner that read: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” As she explained: "I was doing this because the mass of non-qualified women could not demonstrate in the same way, and I was to that extent their spokeswoman. It was the crude fact of women’s political disability that had to be forced on an ignorant and indifferent public, and it was not for any particular Bill or Measure or restriction that I was putting myself to this loss and inconvenience by refusing year after year to pay income tax, until forced to do so by the powers behind the Law."

This resulted in her Hammersmith home being besieged by bailiffs for six weeks. "Towards the end of June, the time was approaching when, according to information brought in from outside the Crown had the power to break open my front door and seize my goods for distraint. I consulted with friends and we agreed that as this was a case of passive resistance, nothing could be done when that crisis came but allow the goods to be distrained without using violence on our part. When, therefore, at the end of those weeks the bailiff carried out his duties, he again moved what he considered sufficient goods to cover the debt and the sale was once again carried out at auction rooms in Hammersmith. A large number of sympathisers were present, but the force of twenty-two police which the Government considered necessary to protect the auctioneer during the proceedings was never required, because again we agreed that it was useless to resist force majeure when it came to technical violence on the part of, the authorities." (39)

Montefiore's campaign was supported by Annie Kenney and Teresa Billington-Greig but did not find favour with the leadership of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) and "no effort was ever made to organise the refusal by women to accept laws made for women without their consent. This changed in October 1909 when the Women's Freedom League (WFL) established the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL). (40)

The first member to take part in the campaign was Dr. Octavia Lewin. It was reported in The Daily Chronicle that the "First Passive' Resister", was was to be taken to court. It was announced in the same report that "the Women's Freedom League intends to organise a big passive resistance movement as a weapon in the fight for the franchise." (41)

Over the next few years over 220 women took part in this campaign. This included Janie Allan, Charlotte Despard, Beatrice Harraden, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Cicely Hamilton, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Emma Sproson, Margaret Nevinson, Octavia Lewin, Henria Williams, Violet Tillard, Edith Zangwill, Sophia Duleep Singh and Clemence Housman.

Sylvia Pankhurst, the author of The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931): has argued: "Tax resistance and resistance to enumeration under the Census of that year were mild forms of militancy now in vogue. The Women's Freedom League had hoisted the standard of 'no vote, no tax' in the early days of its formation, and Mrs. Despard and others had suffered a succession of distraints, to the accompaniment of auction sale protest meetings... In May, 1911, two women were imprisoned for refusal to take out dog licences. A little later, Clemence Housman, sister of the author-artist, Laurence Housman, was committed to Holloway till she should pay the trifling sum of 4s. 6d., but was released in a week's time, having paid nothing." (42)

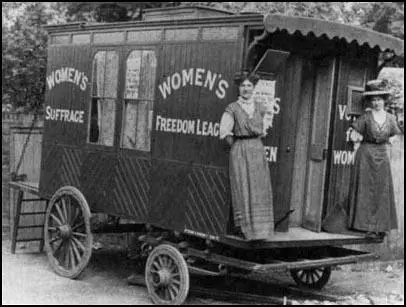

outside the offices of the Women's Suffrage League (c.1910)

It was Women's Freedom League policy of "no taxation without representation" meant that women often went to prison for keeping a dog without a licence. In 1911 Emma Sproson served two terms of imprisonment in Stafford gaol for this offence. They court also ordered her dog to be shot. (43)

Frank Sproson wrote in The Vote: "The humiliating position of the married woman, especially the working woman, is admitted by all Suffragists; but I never realised that she was such an abject slave so clearly as when I stood in the Wolverhampton Police Court, side by side with my wife, charged with aiding and abetting her to keep a dog without a license. The only evidence submitted by the prosecution (the police) that I actually did anything was that I presided at two meetings in support of the "No Vote, No Tax" policy of the Women's Freedom League. That I said anything that was not fair comment on the general policy of militancy there was no evidence to show; if, then, on this point I was liable, then all supporters of militancy are equally so. But I do not believe it was on this evidence that I was convicted. No. The dog was at my house, and cared for by my children during my wife's absence. In the eyes of the law, I was lord and master, so that my offence, therefore, was not that I did anything, but rather that I did not do anything." (44)

Members of the Women's Freedom League refused to pay several different taxes including national insurance, Imperial taxes dog licences, duties on carriages and carts and inhabited house duty. In other branches, members tended to make their resisting colleagues' cases the focus of particular campaigns, as in Brighton where the entire branch rallied to support the actions of their secretary and treasurer who had their goods seized and in lieu of their uncollected inhabited house duty in Edinburgh the members resisted paying taxes on the branch's bank interest, and amiably dismissed the Sheriff Officer when "he called to expostulate with us." (45)

One of the most successful cases of tax resistance was carried out by Kate Harvey, a close friend of Charlotte Despard, at her home in Bromley, Kent. In May 1913 she managed to barricade herself into her home against officials attempting to collect the heavy fines imposed on her for her refusal to pay taxes. Accounts of the subsequent sale of her property reported large numbers of sympathizers crowding into the auction and bidding one penny for all the items put up for sale. In the Woman's Freedom League's Annual Report for 1913 it was recorded as "one of the most effective protests we have ever made!", and noted with satisfaction that the Government had made a loss of 7/- on the proceedings." (46)

Women's Coronation Procession

Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) decided to organise a Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17 June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. Christabel Pankhurst later wrote in Unshackled (1959): "Never had a year begun in so much hope. It might be coronation year for the women's cause as well as for the King and Queen." (47)

Other suffrage organisations including the Women's Freedom League (WFL), Church League for Suffrage, Actresses' Franchise League and Artists' Suffrage League agreed to join the march. It was argued that "Everything depends on numbers, and if the deputation is sufficiently large, the authorities will be placed in an insurmountable difficulty." (48)

In an attempt to get a large turnout women canvased door to door, distributed handbills, fly-posted, carried flags in the streets and chalked announcements on pavements. WSPU opened pop-up shops all over London that sold mass-produced, branded suffragette merchandise. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence came up with the idea of publicizing the march by the distribution of a quarter of a million purple, white and green mock railway tickets. (49)

Kate Harvey organized the procession for the WFL and Edith Downing and Marion Wallace-Dunlop played this role for the WSPU: As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "This represented an immense amount of work. The creation of a wide range of costumes to dress those taking part in the Historical Pageant was particularly taxing. Groups, suitably attired, representing women of renown from the 'early Middle Ages, the Reformation period and in recent history', each carrying an appropriate banner, were designed to impress onlookers with the scope of women's public work through the centuries." (50)

The day before the march took place Prime Minister Herbert Asquith sent a message that convinced the WSPU leadership that votes for women were about to be granted. Christabel Pankhurst wrote: "how much relieved we are by the Prime Minister's message which does really seemed to give us an assurance on which we can depend and can make the basis of our work for the coming months." (51)

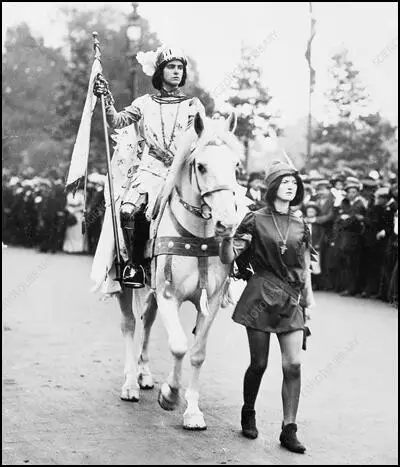

Charlotte Despard led the procession on behalf of the WFL. The Vote reported: "At half-past five the procession started from the Embankment and came swinging along at a good pace up Northumberland Avenue. The roads were packed with such dense crowds that in some parts the police had considerable difficulty in clearing a way for it… Forty thousand women's marching through London forty thousand women walking five abreast, with pennants flying abreast, with pennants flying, banners held aloft, colours of every hue and shade and gradation blazing in the sun; forty thousand women with faces to the dawn, women of every rank and party and creed and race and colour, women old and young, rich and poor; comrades all in the cause of freedoom." (52)

Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) was led by 19-year-old Margery Bryce, dressed as the WSPU's patron saint, Joan of Arc, led the procession on a white horse and in full armour. Her sister, Rosalind Bryce, aged 16, dressed as a medieval page, led the horse by the bridle. (Their father, Annan Bryce, MP for the Inverness Burghs, was completely opposed to votes for women. They were followed by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Mabel Tuke. (53)

The Women's Freedom League used banners that celebrated some of their successful activities such as the Women's Tax Resistance League campaign. They had a banner that explained how Helen Fox and Muriel Matters managed to chain themselves to the Ladies' Gallery Grille of the House of Commons in October 1908. They also had a banner Bermondsey By-Election protest by Alison Neilans and Alice Chapin on in October 1909. (54)

The women marched to seventy-five bands and held over a thousand embroidered and painted banners. 700 women were clothed in white to represent suffragette prisoners. The "Famous Women's Pageant" had twenty suffragettes dressed up as notable women from the past, including, Josephine Butler, Florence Nightingale, Elizabeth Fry, Charlotte Bronte, Mary Somerville and Grace Darling. (55)

The march impressed the newspapers. The Daily Chronicle remarked: "Saturday's remarkable procession in London served as a prelude to the inevitable triumph." (56) The Daily Mirror praised the large number of working-class women who were dressed as mill workers and weavers. "These brave tired women, who had left their homes to demonstrate for their fellow-toilers, were loudly cheered by the crowd." (57)

1911 Census Campaign

The Women's Freedom League decided to ask its members to boycott the 1911 Census. Constance Tite was placed in charge of the project. She announced on 18th February: "The subscription list for the Census Protest has been opened, and we hope that all members and sympathisers will send us a donation as soon as possible. The idea is being greeted with enthusiasm everywhere when we hold meetings, and there seems to be no doubt that if all our members give all the help they can by persuading others to join in evading the Census, and by collecting money, it ought to have an overwhelming effect, as it opens an entirely new form of militant protests." (58)

The Portsmouth branch planned events, which including hiring a hall and sleeping in other members homes. All these plans were told to local reporters by the WFL branch secretary Sarah Whetton, who stated that nearly one hundred supporters were intending to resist. In Manchester sixteen houses were placed at the branch's disposal, and in Edinburgh it was reported that the numbers taking part in the protest had "reached four figures". Members later recorded some unusual methods they used to avoid detection. (59)

Katherine Vulliamy and her husband Edward Vulliamy removed themselves from the 1911 Census but the form was completed by a census registrar who suspected that the Vulliamy family and two "female visitors" were residing at the Vulliamy family home at Maitland House, Barton Road, Cambridge, on the night of the census. The census registrar notes that Edward Vulliamy was working as a "College Tutor" and employed three domestic servants at the family home. (60)

Two Swansea members, Clare Neal and Emily Phipps, recalled how they had spent the night in a cave on the Gower coast with friends before going to work the following day as usual. (61) The Vote reported that the campaign had been a great success: "The most effective protest yet made by women against government without consent.... The census of 1911 has been made memorable by the organised revolt of women." (62)

The Census campaign increased the size of its membership. By 1913 the Women's Freedom League had 61 branches throughout Britain with an overall membership of about 4,000 people. This compared to the 24 branches of the Women's Social and Political Union and the 460 branches of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. (63)

Charlotte Despard and the WFL

After Teresa Billington-Greig resigned from the Women's Freedom League, Charlotte Despard became its most dominant figure. Some members began to complain about her autocratic style of leadership. One sympathetic journalist, Henry N. Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage, compared her to the way Emmeline Pankhurst ran the Women's Social and Political Union. (61)

Seven members of Women's Freedom League National Executive Council, Edith How-Martyn, Alison Neilans, Emma Sproson, Katherine Vulliamy, Constance Tite, Bessie Drysdale and Eileen Mitchell, had jointly sent letters to all branches explaining that their president was acting autocratically and blocking the effective work of the NEC. As a result a special conference was organised in April 1912 to discuss this matter. (62)

At the conference one discontent criticised Despard arguing, "I am in favour of democracy... I do not approve of a leader.. I follow a policy, not a personality." Mrs Kathleen Mitchell, an original member of the WFL put forward her views: "The WFL came into existence, in fact it owes its very name to this, that certain people including Mrs Despard, Mrs How Martyn, Mrs Sproson, myself, and many others found it impossible to reconcile their claim for political enfranchisement of women with an autocratic instead of self-governing society... It is with the greatest regret that I have to tell the Conference that my own experience has proved conclusively to me that this principle is in danger of being fatally reversed." (63)

Nina Boyle supported Charlotte Despard who suggested that democracy was secondary to obtaining votes for women. "We are not here as democrats, but as suffragettes, and we are out to get the Vote!". (64) Despard put forward her own explanation of her behaviour. She stated: "I am a democrat. My views are very well known, long long before there was a WFL... Now I am sorry to say that I am what I am. My opinion on these things is before you, and it was before the WFL when it elected me as President. I cannot be tied up. I cannot be told you must say this and you must do that. That is absolutely impossible for me. I must be myself... I simply and solely do what I can to help the WFL, the cause of women and of women's freedom and emancipation... Make someone else your President, or have no President at all, which ever you choose. As I have said already, if the latter is your will, or the former, I shall go out of this room and out of this hall, and those who will, will follow me, and we will continue to work for the suffrage as we have always done. But I am absolutely loyal to the WFL." (65)

As Claire Louise Eustace has pointed out: "Despard's interpretation of democracy differed as much as her colleagues on the NEC from the principles outlined in the constitution. This was a crucial point, because from the discussions which took place at this conference, it is clear that no consensus on the meaning and expression of democracy was possible. This was partly because the practice and principles of militant action favoured strong individual personalities, and quick, spontaneous actions... Charlotte Despard's references to leaving the WFL appear to have decided the matter. The majority wanted to avoid another split in their organisation and this, along with her undeniable popularity among the membership, ensured that the vote of confidence went in Despard's favour by eighteen votes to thirty-five. (66)

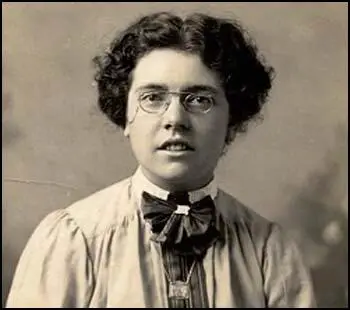

League who resigned in April 1912. This portrait of her was painted by John Lavery in 1908.

As a result of this vote Edith How-Martyn, Alison Neilans, Emma Sproson, Katherine Vulliamy, Constance Tite, Bessie Drysdale and Eileen Mitchell, resigned from the National Executive of the Women's Freedom League. (67) As one newspaper pointed out: "Another split has occurred in the ranks of the suffragettes, the organisation concerned on this occasion being the Women's Freedom League, which has lost several of its most important members… It is interesting to remember that the Women's Freedom League is itself the outcome of a former 'split'. Mrs How Martyn, who was in the early militant days one of the guiding spirits of the Women's Social and Political Union, disagreed, in company with other members of that body, with the present leaders on questions of policy, and they left to form the Women's Freedom League." (68)

The First World War

Most members of the Women's Freedom League, were pacifists, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 they refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL such as Charlotte Despard believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Crusade for a negotiated peace. The Vote attacked Christabel Pankhurst and Millicent Garrett Fawcett, for condemning the women's peace conference. (69)

In November 1914 two Independent Labour Party (ILP) members, Lilla Brockway and Fenner Brockway, established the No-Conscription Fellowship in its campaign against conscription. Several members of the WFL became involved in the organisation. Violet Tillard, Assistant Organising Secretary of the WFL, was appointed General Secretary of the organisation. (70) In May 1918 she was arrested was fined £100 and costs for refusing to furnishing the name and address of the publisher of a leaflet which was circulated by the NCF. (71) When she refused to pay the fine she was sentenced to 61 days' imprisonment. (72)

The WFL continuted the campaign on women's rights. Helena Normanton wrote several pamphlets on the issue of women's pay. In Sex Differentiation in Salary (1914) she argued for equal pay for equal work. In another article she wrote: "During and after the war, many soldiers' wives and widows became the breadwinners for families. Should they be paid according to their sex or their work?" (73)

Qualification of Women Act

The Qualification of Women Act was passed. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The Representation of the People Bill, which doubles the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent." (74)

Three members of the Women's Freedom League stood in the 1918 General Election. Charlotte Despard (Battersea), Elizabeth How-Martyn (Hendon) and Emily Phipps (Chelsea) all argued that women should have the vote on equal terms with men; that all trades and professions be opened to women on equal terms and for equal pay and that women should be allowed to serve on all juries. However, in the euphoria of Britain's victory, the women's anti-war views were very unpopular and like all the other pacifist candidates, who stood in the election, they were defeated. (75)

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 the Women's Social and Political Union disbanded. However, the Women's Freedom League continued the fight for all women to have the vote. As Melanie Phillips pointed out: "Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel, it turned out, would have no part to play in the long agitation ahead for equality of franchise, pay, opportunity, divorce and inheritance." (76)

It has also been argued that the "Women's Freedom League militancy had always been of a carefully defined kind which took the form of non-payment of taxes rather than violence. The most striking feature of the WFL was its loyalty to the equal rights tradition of feminism as is shown by the continuing emphasis on equal franchise and resistance to protective legislation. After 1918 its campaigning methods were of a conventional form indistinguishable from other women's groups." (77)

In 1924 Lilian Lenton was employed as a travelling organizer and speaker for the Women's Freedom League (WFL). During this period she often stayed with Alice Schofield in Middlesbrough. Both women were vegetarians and worked for animal welfare charities. Lenton also wrote for the WFL newsparer, The Vote and toured the country making speeches in favour of all women getting the vote. She was also editor of the WFL's The Women's Bulletin for eleven years. (78)

In July 1925, Lenton spoke at a meeting in Clyde. "Many of the questions the speaker (Lilian Lenton) is asked: several are irrelevant, many simply argumentative, whilst others show a real desire for information and understanding. We have the young men who fear the competition of women in the labour market, alleging that because of it they are unemployed – on what the woman is to live they neither know nor care; and others openly evince apprehension lest, when a woman can earn a decent living, her desire for the ties of matrimony may diminish, and loudly answer in the affirmative when asked if they like the idea that a woman is dependent upon them. Not few in number are the youths of about 16 who assert our "mental and physical" inferiority to the male sex." (79)

Every year on the birthday of John Stuart Mill the Women's Freedom League organized a wreath-laying ceremony by his statue at Victoria Embankment Gardens on his birthday in recognition of his efforts to obtain votes for women with his amendment to the 1867 Reform Act. (80) As Claire Louise Eustace has pointed out: "The choice of Mill was no coincidence, and contained in reports of the event were references to Mill's attempts to extend the liberal principles of individual rights to women, and the WFL's campaign to continue what he had begun back in 1867." (81)

Celebration at his statue in Embankment Gardens on 20th May, 1927

Stanley Baldwin, wanted to change the image of the Conservative Party to make it appear a less right-wing organisation. In March 1927 He suggested to his Cabinet that the government should propose legislation for the enfranchisement of nearly five million women between the ages of twenty-one and thirty. This measure meant that women would constitute almost 53% of the British electorate. The Daily Mail complained that these impressionable young females would be easily manipulated by the Labour Party. (82)

Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was totally opposed to the move and argued that the affairs of the country ought not be put into the hands of a female majority. In order to avoid giving the vote to all adults he proposed that the vote be taken away from all men between twenty-one and thirty. He lost the argument and in Cabinet and asked for a formal note of dissent to be entered in the minutes. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. (83)

A bill was introduced in March 1928 to give women the vote on the same terms as men. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. Many of the women who had fought for this right were now dead including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pankhurst.

Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS during the campaign for the vote, was still alive and had the pleasure of attending Parliament to see the vote take place. That night she wrote in her diary: "It is almost exactly 61 years ago since I heard John Stuart Mill introduce his suffrage amendment to the Reform Bill on May 20th, 1867. So I have had extraordinary good luck in having seen the struggle from the beginning." (84)

The Women's Freedom League and The Vote newspaper continued with its fight for women's equality. As the newspaper pointed out 6th July, 1928: "To have won equal voting rights for women and men is a great victory, but it will be an infinitely greater achievement when we have succeeded in abolishing for ever the 'woman's sphere', 'woman's work', and a 'woman's wage', and have decided that the whole wide world and all its opportunities is just as much the sphere of women, as of men." (85)

The sales of the newspaper fell dramatically and only continued because it was subsidized by Elizabeth Knight and Helena Normanton. Knight became an increasingly important figure in the WFL. According to Stella Newsome: "She (Knight) worked at several hospitals for women and children and was a tower of strength to all her patients.... She became Hon. Treasurer of the League... She was, however, much more than Hon. Treasurer, arduous and difficult as that task has often been... She was an uncompromising fighter for the recognition of an equal moral standard for men and women. She was a strong advocate for women police and urged their inclusion in every police force in the country – their status, promotion and pay to be on equal terms with men." (86)

The Women's Freedom League supported the Six Point Group of Great Britain, which focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: The six original specific aims were: (i) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (ii) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (iii) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (iv) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (v) Equal pay for teachers; (vi) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service. (87)

On 15th October 1933, Elizabeth Knight was knocked down by a car as she was crossing Dyke Road in Brighton. She told a police officer: "It was my fault. I crossed the road without looking." (88) At first she declined to go to hospital, "remarking that she was not much hurt, but he persuaded her to accompany him to hospital." (89) After treatment she was taken to the home of Minnie Turner. On 28th October, pleurisy developed and death occurred on Sunday from heart failure as a result of the effects of the accident. (90)

Knight left most of her considerable fortune to her neice: "Dr Elizabeth Knight, the women's suffrage pioneer, who lived at Gainsborough Gardens, Hampstead, and who died last October from injuries received when knocked down by a motar-car at Brighton, has left £248,467." (91) As a result the The Vote had to stop publication. (92)

Under the leadership of Stella Newsome, Marion Reeves and Dorothy Evans, the Women's Freedom League continued. However, by 1939 it was very much a London-based pressure group of about 3,000 supporters. (93)

The Women's Freedom League continued until 1962 "well beyond the period of campaigning for the suffrage, and the emergence of feminism in the 1910s and 1920s." (94)

Primary Sources

(1) Charlotte Despard, The Vote (30th October 1909)

We hope and believe that through its pages the public will come to understand what the Parliamentary Franchise means to us women. Now it will be both a symbol of citizenship and the key to a door opening out on such service to the community as we have never yet been allowed to render, and therefore it is our earnest hope that our paper will keep its place in the hearts of men and women long after the first victory has been won.

(2) Teresa Billington Greig, The Militant Suffrage Movement, (1911)

The first militant protest was decided upon by Miss Christabel Pankhurst, and announced by mother or daughter to a small number of the more active members of the Union. The body of members knew nothing of the plans until they heard with the public that it had been carried out… It was at this point that the sense of difference of outlook, of which I had always been conscious in my association with Mrs. Pankhurst and her daughter, became acute. I did not approve the line of protest determined upon. It seemed to me to provide a very inadequate outlet for the expression of our rebellion.

(3) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, My Part in a Changing World (1938)

The Women's Social and Political Union when it was first formed had adopted a constitution framed on the lines of that of the Labour Party, to which the Pankhursts and all the original members in Manchester belonged.

The first national conference of delegates was due to take place this month, but some months before this date differences of thought and opinion had begun to manifest themselves amongst some of the members. The Union had grown very rapidly since the foundation of the London headquarters in 1906, and to cope with its demands organiser after organiser had been added to the staff. They were appointed because of their great courage and eloquence, and their ability to control and dominate crowds.

As September approached, it became evident that some influential people who had been attracted by the movement wished to frame a constitution that would substitute the principle of democratic control for that of individual leadership. It seemed to them reasonable and right that, following the practice of other organisations, the W.S.P.U. branches should be accorded the power to criticise and, if they could secure a majority, to amend the policies and the programme of the movement.

But there was another aspect of this question, an aspect acutely realised at headquarters. Newcomers were pouring into the Union. Many of them were quite ill-informed as far as the realities of the political situation were concerned. Christabel, who possessed in a high degree a flair for the intricacies of a complex political situation, had conceived the militant campaign as a whole. In her mind it drew its justifications from the frustrations of fifty years. These frustrations, she maintained, were not due to natural causes, but were directly due to the extremely adroit tactics of successive Governments that had enabled them to avoid dealing with the question. If the suffrage movement was ever to rise from the grave where politicians had led it, tactics equally adroit needed to be employed. She never doubted that the tactics she had evolved would succeed in winning a cause which, as far as argument or reason was concerned, was intellectually won already. She dreaded all the old plausible evasions and she feared the ingrained interiority complex in the majority of women. Thus she could not trust her mental offspring to the mercies of politically untrained minds. Moreover, the very fact that militant action involved individual sacrifice imposed heavy responsibilities upon the leaders of the campaign. Individuals who were ready to make the sacrifice that militancy entailed had to be sustained by the assurance of complete unity within the ranks. I agreed with this view of the situation, although I felt that it would be a difficult one to sustain in the conference. The issue to be raised was that of "democracy." It was an irony that this question of principle should come up in a political union which was to win votes for women. It became evident that, young as the militant movement was, it had to meet a crisis the solution of which would influence its future history.

While these clouds had been slowly gathering at headquarters Mrs. Pankhurst was conducting a campaign of meetings in the north. She knew nothing of the difficulties of the position until she returned to London on the eve of the conference. I shall never forget the gesture with which she swept from the board all the "pros and the cons" which had caused us sleepless nights. ''I shall tear up the constitution," she declared. This intrepid woman when apparently hemmed in by difficulties always cut her way through them.

The next day at the conference she asserted her position as founder of the Union, declared that she and her daughter had counted the cost of militancy, and were prepared to take the whole responsibility for it, and that they refused to be interfered with by any kind of constitution. She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people.

Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to "democracy," and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own.

Thereupon Mrs. Despard, Mrs. How-Martyn and Miss Billington and their followers formed a separate organisation, the Women's Freedom League. The severance was always referred to as "The Split."

(4) Teresa Billington Greig, The Militant Suffrage Movement, (1911)

In September, about a month before the date arranged for the gathering, Mrs. Pankhurst, ignoring the Honorary Secretary, called a Committee meeting, declared the Conference annulled, the Constitution cancelled, and the rights of the members abolished, and proclaimed herself as sole dictator of the movement. She appointed herself secretary, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence treasurer, and Miss Christabel Pankhurst organizing secretary. She chose for herself a committee consisting of paid organisers and two or three women who were willing to lend their names to this purpose.

The clumsy declaration of autocracy broke the spell of many who would willingly have voted away their rights. Those who stuck to the Constitution formed the Women's Freedom League… This reversion to autocracy, this denial of suffrage in their own society to women seeking suffrage in the State, brought to a sudden close to this stage in the progress of militancy.

(5) Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Fate Has Been Kind (1942)

The Pankhursts were not prepared to run the risk of having their carefully thought out policy reversed by newcomers with little political experience, or whittled down by an executive of divided opinions. Mrs. Pankhurst declared herself therefore in sole control of the WSPU and she called on those who believed in her leadership to stand by her. My wife concurred in this decision, and it was accepted by the bulk of the members. The branches became local WSPUs without any control over policy. A minority of women, including Mrs. Despard, Mrs. How Martyn, and Miss Billington, dissented, and formed a democratically controlled body - The Women's Freedom League.

(6) Emma Sproson, letter to Maud Arncliffe Sennett (8th May 1909)

The bruises and scar of the flesh is not the worst we endure in this fearful conflict, I was addressing a large crowd on one occasion when a dirty urchin spit in my face and his expectoration passed out of his lips into mine, I collapsed and now know what had happened. I would have lost any limb I own to have escaped this experience, but more bitter still are the slights and insinuations of those whose sympathy ought to encourage our hopes and strengthen our backs for the conflict. But what ever happens the same motive which stimulated me for the conflict will inspire me to the end. Namely I have a daughter and I can only fulfil my duty to my girl and society by breaking down the fetters of the girls of the future which have bound us down in the past.

(7) Claire Louise Eustace, The Evolution of Women's Political Identities in the Women's Freedom League (1993)

Despard's interpretation of democracy differed as much as her colleagues on the NEC from the principles outlined in the constitution. This was a crucial point, because from the discussions which took place at this conference, it is clear that no consensus on the meaning and expression of democracy was possible. This was partly because the practice and principles of militant action favoured strong individual personalities, and quick, spontaneous actions...

Charlotte Despard's references to leaving the WFL appear to have decided the matter. The majority wanted to avoid another split in their organisation and this, along with her undeniable popularity among the membership, ensured that the vote of confidence went in Despard's favour by eighteen votes to thirty-five. The implications of this vote were felt the following week when the seven discontented members resigned from the League, and so the WFL lost the skills of these committed women. Among them were Marion Coates-Hansen, Edith How-Martyn and Alison Neilans, who went on to pursue different paths in the emerging women's movement.

(7) In 1914 the Women's Freedom League refused the call off its campaign for women's suffrage. Charlotte Despard, the leader of the Women's Freedom League was a pacifist who refused to become involved in the war effort. In 1916 she made a speech explaining her views.

The great discovery of the war is that the Government can force upon the capitalistic world the superlative claims of the common cause… The Board of Education has concluded that one in six childhood was so physically and mentally defective as to be unable to derive reasonable benefit from the education, which the State provides… My message to the government is 'take over the milk as you have taken over the munitions'.

(8) In 1919 the Women's Freedom League held a public meeting to celebrate women over thirty obtaining the vote. One of the speeches was made by eighty-three year old Charlotte Despard.

I have seen great days, but this is the greatest. I remember when we started twenty-one years ago, with empty coffers… I never believed that equal votes would come in my lifetime. But when an impossible dream comes true, we must go on to another. The true unity of men and women is one such dream. The end of war, of famine - they are all impossible dreams, but the dream must be dreamed until it takes a spiritual hold.

(9) The Vote (6 July, 1928)

To have won equal voting rights for women and men is a great victory, but it will be an infinitely greater achievement when we have succeeded in abolishing for ever the 'woman's sphere', 'woman's work', and a 'woman's wage', and have decided that the whole wide world and all its opportunities is just as much the sphere of women, as of men.

"I have no intention of attacking the institution of marriage in itself - the life companionship of man and woman; I merely wish to point out that there are certain grave disadvantages attaching to that institution as it exists today. These disadvantages I believe to be largely unnecessary and avoidable; but at present they are very real, and the results produced by them are anything but favourable to the mental, physical and moral development of woman!"

(10) Cicely Hamilton, Marriage as a Trade (1912) page vi

I have no intention of attacking the institution of marriage in itself - the life companionship of man and woman; I merely wish to point out that there are certain grave disadvantages attaching to that institution as it exists today. These disadvantages I believe to be largely unnecessary and avoidable; but at present they are very real, and the results produced by them are anything but favourable to the mental, physical and moral development of woman!

(11) Stella Newsome, Women's Freedom League, 1907–1957 (1960)

Dr Elizabeth Knight trained at the London School of Medicine for Women at the same time as Dr Louise Garrett Anderson. She worked at several hospitals for women and children and was a tower of strength to all her patients.

It was, however, as a stalwart champion of the rights of women that we best remember Dr Knight. She was brought into the WFL in the early days by Dr Lewin and in 1908 served two weeks imprisonment for calling at 10 Downing Street to ask Mr Asquith why he had promised Manhood Suffrage in answer to the demand for votes for women. She took an active part in the Census protests of 1911, was prosecuted on several occasions for refusing to pay taxes as a protest against women's continued disenfranchisement, and was imprisoned on two occasions for these protests.

In 1913 she became Hon. Treasurer of the League and so continued until her death in 1933.

She was, however, much more than Hon. Treasurer, arduous and difficult as that task has often been. Throughout the war, the WFL urged on by Dr Knight, was always first in the field to attack any attempt to re-introduce any provisions of the odious Contagious Diseases Acts. She was untiring in her opposition to the hateful 40D Regulation which involved the compulsory examination of women suspected of having transmitted venereal disease to a member of his Majesty's Forces. Largely through her instigation the League was responsible for getting nearly 150 resolutions passed against it in various parts of the country.

She was an uncompromising fighter for the recognition of an equal moral standard for men and women. She was a strong advocate for women police and urged their inclusion in every police force in the country – their status, promotion and pay to be on equal terms with men.

It was a happy day when she took Mrs Despard to the House of Lords on 2 nd July, 1928, to hear the Royal Assent to the Equal Franchise Act, but she was never under the illusion that franchise meant complete freedom to women.

Those of us who worked with her will always remember her friendship, her loyalty and the staunch support she always gave her fellow members.

(12) Stella Newsome, Women's Freedom League, 1907–1957 (1960)

Among the many well-known women who have served the Women's Freedom League the most outstanding is Mrs Charlotte Despard whose name is known throughout the world.

On the foundation of the League in 1907 she became its first president, and so continued for many years. She was a picturesque and gracious personality with indomitable courage in opposing all injustice and oppression wherever they were shown.

Her happy marriage having terminated with the death of her husband in 1890, she turned to social service. She became a member of the Lambeth Board of Guardians, established a working men's club in Battersea, and a clinic for members and babies. These later developed into the Nine Elms Settlement which did noteworthy work in both wars.

Mrs Despard's struggles for social reform convinced her of the need for women's enfranchisement and she joined the suffrage movement in the early days of this century. In 1906 she was working in the militant movement. Believing firmly that women who were demanding self-government from the State should have self-government in their own organisation she became founder of the Women's Freedom League. As first President of the League she shirked nothing – the difficulties of finance, of organisation, of propaganda were difficulties to be overcome. At any meeting, indoors or outdoors, large or small, she gave of her best.

Many times her goods were seized for non-payment of taxes which she refused to pay on the grounds of "no taxation without representation." Three times she was imprisoned for going on a deputation to the House of Commons. She was absolutely fearless, and her courage, both physical and moral, was an inspiration to all.

When women over 30 obtained the vote, Mrs Despard made up her mind that there must be no cessation of activity until women had full voting rights with men. She was well over 80 when she headed a procession to Hyde Park to make their demands.

In 1919 she stood as Labour candidate for Battersea but, although she polled over 5,000 votes, she failed to secure election to the House of Commons. Soon afterwards she returned to Ireland to live.

She was a great and valiant woman who met the strain and stress of life with refreshing gaiety. She truly loved freedom which she whole-heartedly believed to be the birthright of every human being irrespective of race, creed or sex.

(13) Claire Louise Eustace, The Evolution of Women's Political Identities in the Women's Freedom League (1993)

Earlier contributions by members like Margaret Wynne Nevinson had already problematised the arguments that it was men's sexual double standard alone which created the evils of prostitution. In 1911 she argued in The Vote: "prostitution is an economic problem, rather than a moral one, not to be hedged by the philanthropic palliative or one-sided legislation." (The Vote, March 11th 1911) Nevinson argued that it was the low wages of women workers which forced them into prostitution and so the situation could only be challenged when women earned a living wage."