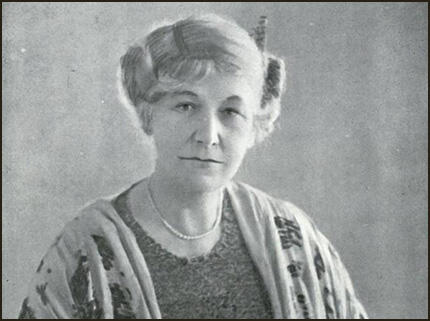

Dora Montefiore

Dora Fuller, the eighth child of Francis and Mary Fuller, was born on 20th December, 1851. Her father was a land surveyor and railway entrepreneur. She was educated at home at Kenley Manor, near Coulsdon, and then at a private school in Brighton. According to Olive Banks: "There was a deeply affectionate relationship between father and daughter, and he obviously made great efforts to stimulate her intelligence.... she became his amanuensis, travelling with him and helping him prepare papers for the British Association and Social Science Congresses."

In 1874 she went to Australia, where she met George Barrow Montefiore, a wealthy businessman. After their marriage on 1st February 1881, they lived in Sydney, where their daughter was born in 1883 and their son in 1887. Her husband died on 17th July 1889. Although she had no personal grievances, she discovered that she had no rights of guardianship over her own children unless her husband had willed them to her. She therefore became an advocate of women's rights and in March 1891 she established the Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales.

On returning to England in 1892 she worked under Millicent Fawcett at the National Union of Suffrage Societies. She also joined the Social Democratic Federation and eventually served on its executive. She also contributed to its journal, Justice.

During the Boer War Montefiore "refused willingly to pay income tax, because payment of such tax went towards financing a war in the making of which I had had no voice." As she pointed out in her autobiography, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927): "In 1904 and 1905 a bailiff had been put in my house, a levy of my goods had been made, and they had been sold at public auction in Hammersmith. The result as far as publicity was concerned was half a dozen lines in the corner of some daily newspapers, stating the fact that Mrs. Montefiore’s goods had been distrained and sold for payment of income tax; and there the matter ended."

During this period she became close friends with Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy who had also become dissatisfied with the slow progress towards women's suffrage. Both women joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) soon after it was formed in 1905. She worked closely with Sylvia Pankhurst and Annie Kenney as part of their London campaign.

In 1906 Dora Montefiore refused to pay her taxes until women were granted the vote. Outside her home she placed a banner that read: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” As she explained: "I was doing this because the mass of non-qualified women could not demonstrate in the same way, and I was to that extent their spokeswoman. It was the crude fact of women’s political disability that had to be forced on an ignorant and indifferent public, and it was not for any particular Bill or Measure or restriction that I was putting myself to this loss and inconvenience by refusing year after year to pay income tax, until forced to do so by the powers behind the Law."

This resulted in her Hammersmith home being besieged by bailiffs for six weeks. "Towards the end of June, the time was approaching when, according to information brought in from outside the Crown had the power to break open my front door and seize my goods for distraint. I consulted with friends and we agreed that as this was a case of passive resistance, nothing could be done when that crisis came but allow the goods to be distrained without using violence on our part. When, therefore, at the end of those weeks the bailiff carried out his duties, he again moved what he considered sufficient goods to cover the debt and the sale was once again carried out at auction rooms in Hammersmith. A large number of sympathisers were present, but the force of twenty-two police which the Government considered necessary to protect the auctioneer during the proceedings was never required, because again we agreed that it was useless to resist force majeure when it came to technical violence on the part of, the authorities."

In October 1906 she was arrested during a WSPU demonstration and was sent to Holloway Prison. "The cells had a cement floor, whitewashed walls and a window high up so that one could not see out of it. It was barred outside and the glass was corrugated so that one could not even get a glimpse of the sky; and the only sign of outside life was the occasional flicker of the shadow of a bird as it flew outside across the window. The furnishing of the cell consisted of a wooden plank bed stood up against the wall, a mattress rolled up in one corner, two or three tin vessels, a cloth for cleaning and polishing and some bath brick. On the shelf were a Bible, a wooden spoon, a salt cellar, and one other book whose name I forget, but I remember glancing into it and thinking it would appeal to the intelligence of a child of eight. There was also a stool without a back, and inside the mattress when unrolled for the night and placed on the wooden stretcher were two thin blankets, a pillow and some rather soiled-looking sheets. One tin utensil was for holding water, the second for sanitary purposes, and the third was a small tin mug for holding cocoa."

Montefiore disagreed with the way Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the WSPU and in 1906 she left the organisation. However, she remained close to Sylvia Pankhurst, who shared a belief in socialism. Montefiore was not alone in her opinions of the leadership of the WSPU. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

In 1907 Montefiore joined the Adult Suffrage Society and was elected its honorary secretary in 1909. She also remained in the Social Democratic Federation. Montefiore's biographer, Karen Hunt, has pointed out: "Within the SDF she developed a woman-focused socialism and helped set up the party's women's organization in 1904. An energetic although often dissident worker for the SDF until the end of 1912, Montefiore resigned from what had become the British Socialist Party as an anti-militarist."

Montefiore was pre-eminently a journalist and pamphleteer. She wrote a women's column in The New Age (1902–6) and in the Social Democratic Federation journal Justice (1909–10). Later she was to write for the Daily Herald and the New York Call. Most of her pamphlets were on women and socialism, for example, Some words to Socialist women (1907). Montefiore was also interested in an international apprach to women's suffrage and socialism and travelled a great number of congresses and conferences in Europe, the United States, Australia, and South Africa.

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF).

It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Early members included Dora Montefiore, Tom Bell, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, Rose Cohen, Tom Mann, Ralph Bates, Winifred Bates, Rose Kerrigan, Peter Kerrigan, Bert Overton, Hugh Slater, Ralph Fox, Dave Springhill, William Mellor, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart, Shapurji Saklatvala, George Aitken, Dora Montefiore, Sylvia Pankhurst and Robin Page Arnot. McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers.

After the death of her son from the effects of mustard gas in 1921 (he had been gassed while serving on the Western Front during the First World War), she joined his widow and children in Australia. In 1927 she published her autobiography, From a Victorian to a Modern.

Dora Montefiore died on 21st December 1933, at her home in Hastings, and was cremated at Golders Green, Middlesex.

Primary Sources

(1) Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927)

The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon the Victoria Street Union of Suffrage Societies.

Mrs. Elmy, one of the most wonderful women who devoted her life and her intellectual powers to the cause of the emancipation of women, paid constant visits to London from her home in Cheshire, with the object of stirring up what seemed to be the dying embers of suffrage activities. She knew all the Members of Parliament who had at any time expressed in words, or who had helped with pen or with action our cause; and at the time of these visits to London (usually at the period of the promised debates in Parliament on a Suffrage Bill), she would visit these Members in the Lobby and do her best to stir them into action. The late Mr. Stead, who was a great admirer of hers, would frequently help her to get up small private meetings of sympathisers and workers, and all of us who were looking for a lead in suffrage matters, welcomed these quaint and earnest appearances of hers in London, and derived encouragement from her experience of Parliamentary procedure and intense spiritual enthusiasm. She usually stayed at my house when she came to town, and I had the privilege of accompanying her when she interviewed Members of Parliament or other sympathisers. She must have been then between sixty and seventy, very small and fragile, with the brightest and keenest dark eyes and a face surrounded with little white ringlets. She was an old friend of and fellow-worker with Josephine Butler and of John Stuart Mill, and in those days had been an habituée of what was then known as the “Ladies’ Gallery” in the House of Commons. There, behind the grille, where they could see but not be seen by the Members of the House, these and other devoted women had sat night after night listening to the debates on the Contagious Diseases Acts, which raised questions that concerned their sex as much, if not more, than they did that of the men who were discussing them. This loyalty in the cause of their fellow-women who, they realised, suffered so severely under the C.D. Acts, brought them insult and opprobrium, but it also brought them many of the truest and loyalest friends that women ever possessed; and, as we know, the cause they stood for triumphed in the end.

My friendship with Mrs. Elmy and work with her continued during many years and our correspondence, between the periods of her visits to town, was continuous; I was keeping her au courant with what was going on in London, and she interpreting, encouraging, sending me voluminous newspaper cuttings and helping forward my work in every way in her power with loving counsels and wisest advice. She never faltered in her belief that women’s political enfranchisement was very near at hand, although, time and again, politicians betrayed and jockeyed us, while men who feared our influence in public life, insulted our efforts and talked out our Bills. Mrs. Browning wrote: “It takes a soul to move a body,” and I often thought that it was the little white hovering soul of Mrs. Wolstenholme Elmy which eventually moved a somewhat inert mass of suffrage endeavour and set it on the road of militant activity. At any rate, she hailed with delight the work of the “Women’s Social and Political Union,” which flared up like a torch in Manchester under the guidance of Mrs. Pankhurst and her daughters, and in London, under that of a group of women, myself included, who undertook to attend political meetings and question speakers about their intentions towards the enfranchisement of women, keeping that before the meeting as our supreme aim and if necessary, holding up proceedings until an answer was obtained. Early in 1906 Christabel Pankhurst wrote me from Manchester that Annie Kenney was coming up to town to help us carry on the fight and she wanted to find a place to stay at in the East End of London, where she could get into touch with East End working women. As I was already in touch with many of these women, I was able to find the place Annie Kenney required with Mrs. Baldock, the wife of a fitter, at 10, Eclipse Road, Canning Town, and she and Teresa Billington helped much in our London work. Before this, however, some of us had been on a deputation to Mr. Campbell Bannerman in Downing Street, and the illustrated papers came out with pictures of a group of us, including Mrs. Drummond, Mrs. Davidson, Mrs. Rowe and myself, standing on the steps of No. 10, Downing Street, trying to persuade the elderly manservant to let us in and interview the Prime Minister. We had a long and rather amusing argument with this manservant, who evidently was at his wits’ end to know what to do with us, so politely pertinacious were we. Finally, after closing the door on us more than once, while he went into the house with our messages, he returned to say that Mr. Ponsonby, the Prime Minister’s Secretary, would see two of us, and Mrs. Drummond and myself were deputed to interview him, while the rest of the deputation remained on the doorstep. Our interview was not wholly successful, inasmuch as we could obtain no definite promise that the Prime Minister would receive a deputation, but I think we succeeded in making Mr. Ponsonby understand that we were in deadly earnest about the matter and that if we did not get some definite Governmental promise or assurance that the Liberals, for whom women had worked so loyally to place in power, would fulfil their pre-electoral pledges, we would find other means, unconstitutional if necessary, to force them to do so.

Among the electoral meetings we attended in order to question the candidates on the subject of the enfranchisement of women, I remember one meeting specially at the. Queen’s Hall, Regent Street, when Mr. Asquith was to support the candidature of Mr. Chiozza-Money, when I obtained tickets for Annie Kenney in the orchestra and myself and Mrs. Baldock in the stalls. The meeting was a huge packed one, and the audience while waiting sang the Land Song and other favourite Liberal ditties. It was in excellent humour with itself for it smelt victory and knew that the spoils of office were within the grasp of Liberalism. It was not in a humour to brook interruptions. The applause when Mr. and Mrs. Asquith entered was noisy and prolonged. That gentleman’s speech was punctuated with cheers, then a shrill voice came from the orchestra seats, “What are you going to do for women?” There was a roar of displeasure from the audience. Again the voice rose: “Votes for Women!” There was a rush of stewards for the spot from whence the voice proceeded. Many of the audience rose to their feet, a signal was given and the organ began to play. Mr. Asquith sat down and beamed a fat smile, Mrs. Asquith an acidulated one. There was a prolonged scuffle in the orchestra punctuated with cried of “Votes for Women,” and finally Annie Kenney was carried out. The organ ceased to play, and Mr. Asquith continued his speech.

It was then my turn and at the next opportunity that Mr. Asquith gave when rehearsing the Liberal programme, I rose to my feet and asked if the Liberals were returned to power, what they were going to do for the emancipation of women. A gasp of outraged surprise filled the stalls and people round me asked me to sit down, but I insisted: “Will the speaker tell the audience what the intention of the Government is about the enfranchisement of women?” Stewards approached me and one of them said “Will you write the question and send it up to the platform.” The ladies round me hearing this said: “Yes, write the question and send it up by the stewards.” This I did and I watched the paper being passed to Mr. Asquith and read by Mrs. Asquith, who sat just behind him; again they both smiled sarcastically, but no answer was vouchsafed. I rose to my feet again to protest that wanted an answer, but those near me and the stewards who were now surrounding me, said: “Wait till the end of the meeting, and the other speakers have made their speeches, and he will then give you an answer.” I, believing that this assurance had been given to the stewards, waited till the end of the meeting, but when that end came those on the platform walked out without vouchsafing a reply to a question voiced by a delegate from organised women. This shows the contempt with which the Liberal Leaders met the women’s organised demand for enfranchisement, and it was the cause of many of the angry meetings in front of Mr. Asquith’s house during the course of the manifestations which followed.

(2) Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927)

Between the time of my return to England in 1901, and 1904, when I began my first public protest against the payment of income tax, while I still had no political representation, my mind was slowly maturing and my heart opening out on the subject of many social questions, besides that of the political vote. But my two children were at school and I lived mostly in the country or stayed with my mother at Hove, so there was little chance of working in London. But I was able, soon after the new Local Government Act, allowing women to sit on Parish and Urban District Councils, came into force to do some organising in Sussex for the Local Government Society in Tothill Street, and this work, undertaken voluntarily, gave me a great insight into the working of the Act. I visited during that time every class of person who was likely to be interested in the working of the Act, from cottagers to Bishops, and learnt how everyone was looking forward to better water supplies and better lighting for the villages, not to speak of parish halls, libraries and baths, of which the Act was full of suggestions; but, alas, when talking things over with those experienced in Local Government, I soon became convinced that it was merely the skeleton of an Act, whose dry bones must be clothed with money, if its provisions were effectually to be carried out. However, I obtained in the end promises from two or three women to stand for the Councils, though at the same time I had more than one angry interview with Chairmen of Councils who threatened to resign if women were ever elected; for they asserted it would be quite impossible to discuss questions of drainage with women present. After this experience I felt how deficient my knowledge of drainage, ventilation and kindred subjects was and I took a course of studies at the Health Society in Berners Street. I would recommend the course to any young woman who has a home of her own to look after, even if she does not contemplate sitting on a Council. I have never regretted having acquired the special knowledge that the course offers, either when there has been illness in the home, or when taking a new house, when I have surprised the landlord by pointed enquiries into drainage, cisterns for drinking water, flues of chimneys, etc.

In 1900 I had my first experience of an International Women’s Congress which was held in Brussels, where I spoke in French, giving the history of our English movement, and spoke of the Boer War, which was undertaken to enfranchise Englishmen in South Africa, while, now that we Englishwomen asked to be enfranchised we were laughed at, and often insulted in Parliament. Monsieur Jules Bois writing in the Figaro of 10th September, described the two Englishwomen at this Congress: “Mrs. Montefiore, poéte délicieuse et humanitaire, et Lady Grove, belle et philosophe comme Hypatie font toutes deux partie de l’Association des ‘Suffragistes Pratiques’ qui ne soutiennent en Angleterre que les candidats favorables aux femmes. Elles méritent de n’être pas oubliées.” As this Congress took place during my children’s holidays I took them first with a holiday governess to a little seaside place near Dieppe, and leaving them under her care, went on to Brussels for the week and then returned to spend the rest of the holidays with them. But the time was approaching when my boy would have to go to the preparatory school for St. Paul’s in London, so we had to leave our little home in Sussex and migrate up to town, where we eventually settled at the Upper Mall, Hammersmith, so as to be near St. Paul’s School.

I was then able to undertake much more social and political work, and was elected by the Hammersmith Trades Council on the Hammersmith Distress Committee, which had to do with the acute unemployment of that day. The work of these Distress Committees was to me harassing and very depressing, for it seemed to me that the men who had formulated all unemployment schemes had veritably tried how not to do things. Long lists of men out of work were put before us week after week, and name after name was struck out as not being eligible for the few jobs of relief work that were going. No unmarried man was eligible, though it always seemed to me that they were the men who should be sent away, while the married men should be given work in the district. But no; married men were sent to camps for reclaiming land on the East Coast or to the very excellent Garden Colony at Hollesley Bay, and they had often been out of work so long that they had scarcely a shirt over which to button their miserable coat. Result, the men were struck down with pneumonia or some other winter complaint brought on by the icy winds of the East Coast. Then, some of us members of the Distress Committee got up an unofficial fund for buying warm winter shirts and boots for the men who were sent to these camps. I was entrusted with the buying of these garments, and this brought me into touch with the families of the unemployed, and I saw at first hand all the hopelessness and cruelty of their position. Also I saw that we, by sending the husbands away, were doing a great harm to family life, for the wives, in order to increase their scanty allowances, in many cases took in a lodger, which did not make for the happiness of domestic life, when once a month the husband was allowed home for a week-end. It will scarcely be believed nowadays that a man working in one of these unemployed camps received as pocket money 6d. a week, and that from ten to twelve shillings a week was all that was allowed to his wife and family. As we members of the Distress Committee left the Town Hall week after week, we were met in the passages and at the entrance with rows of hunger-stricken faces asking us with anxious eyes whether a job had been found for one or other of them, and in my imagination I used to see the dejected or desperate man return home with the same hopeless words, “No luck” flung into the almost empty room where the family was huddled. Is it surprising that I, with other women like Mrs. Despard, marched again and again at the head of the Unemployed Demonstrations, trying to plead their case with the Government of the day? And this was over twenty years ago! And still the people are patient, and are waiting for a Conservative Government “to do something.” Will they always wait? That is the question which prevents some of the Ministers sometimes from sleeping soundly.

(3) Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927)

I had already, during the Boer War, refused willingly to pay income tax, because payment of such tax went towards financing a war in the making of which I had had no voice. In 1904 and 1905 a bailiff had been put in my house, a levy of my goods had been made, and they had been sold at public auction in Hammersmith. The result as far as publicity was concerned was half a dozen lines in the corner of some daily newspapers, stating the fact that Mrs. Montefiore’s goods had been distrained and sold for payment of income tax; and there the matter ended. When talking this over in 1906 with Theresa Billington and Annie Kenney, I told them that now we had the organisation of the W.S.P.U. to back me up I would, if it were thought advisable, not only refuse to pay income tax, but would shut and bar my doors and keep out the bailiff, so as to give the demonstration more publicity and thus help to educate public opinion about the fight for the political emancipation of women which was going on. They agreed that if I would do my share of passive resistance they would hold daily demonstrations outside the house as long as the bailiff was excluded and do all in their power outside to make the sacrifice I was making of value to the cause. In May of 1906, therefore, when the authorities sent for the third time to distrain on my goods in order to take what was required for income tax, I, aided by my maid, who was a keen suffragist, closed and barred my doors and gates on the bailiff who had appeared outside the gate of my house in Upper Mall, Hammersmith, and what was known as the “siege” of my house began. As is well known, bailiffs are only allowed to enter through the ordinary doors. They may not climb in at a window and at certain hours they may not even attempt an entrance. These hours are from sunset to sunrise, and from sunset on Saturday evening till sunrise on Monday morning. During these hours the besieged resister to income tax can rest in peace. From the day of this simple act of closing my door against the bailiff, an extraordinary change came over the publicity department of daily and weekly journalism towards this demonstration of passive resistance on my part. The tradespeople of the neighbourhood were absolutely loyal to us besieged women, delivering their milk and bread, etc., over the rather high garden wall which divided the small front gardens of Upper Mall from the terraced roadway fronting the river. The weekly wash arrived in the same way and the postman day by day delivered very encouraging budgets of correspondence, so that practically we suffered very little inconvenience, and as we had a small garden at the back we were able to obtain fresh air. On the morning following the inauguration of the siege, Annie Kenney and Theresa Billington, with other members of the W.S.P.U., came round to see how we were getting on and to encourage our resistance. They were still chatting from the pavement outside, while I stood on the steps of No. 32 Upper Mall, when there crept round from all sides men with notebooks and men with cameras, and the publicity stunt began. These men had been watching furtively the coming and going of postmen and tradesmen. Now they posted themselves in front, questioning the suffragists outside and asking for news of us inside. They had come to make a “story” and they did not intend to leave until they had got their “story.” One of them returned soon with a loaf of bread and asked Annie Kenney to hand it up over the wall to my housekeeper, whilst the army of men with cameras “snapped” the incident. Some of them wanted to climb over the wall so as to be able to boast in their descriptions that they had been inside what they pleased to call “The Fort”; but the policeman outside (there was a police man on duty outside during all the six weeks of a siege) warned them that they must not do this so we were relieved in this respect, from the too close attention of eager pressmen. But all through the morning notebooks and cameras came and went, and at one time my housekeeper and I counted no less than twenty-two pressmen outside the house. A woman sympathiser in the neighbourhood brought during the course of the morning, a pot of home-made marmalade, as the story had got abroad that we had no provisions and had difficulty in obtaining food. This was never the case as I am a good housekeeper and have always kept a store cupboard, but we accepted with thanks the pot of marmalade because the intentions of the giver were so excellent; but this incident was also watched and reported by the Press. Annie Kenney and Theresa Billington had really come round to make arrangements for a demonstration on the part of militant women that afternoon and evening in front of the house, so at an opportune moment, when the Press were lunching, the front gate was unbarred and they slipped in. The feeling in the neighbourhood towards my act of passive resistance was so excellent and the publicity being give by the Press in the evening papers was so valuable that we decided to make the Hammersmith “Fort” for the time being the centre of the W.S.P.U. activities, and daily demonstrations were arranged for and eventually carried out. The road in front of the house was not a thoroughfare, as a few doors further down past the late Mr. William Morris’s home of “Kelmscott,” at the house of Mr. and Mrs. Cobden-Sanderson, there occurred one of those quaint alley-ways guarded by iron posts, which one finds constantly on the borders of the Thames and in old seaside villages. The roadway was, therefore, ideal for the holding of a meeting, as no blocking of traffic could take place, and day in, day out the principles for which suffragists were standing we expounded to many who before had never even heard of the words Woman Suffrage. At the evening demonstrations rows of lamps were hung along the top of the wall and against the house, the members of the W.S.P.U. speaking from the steps of the house, while I spoke from one of the upstairs windows. On the little terrace of the front garden hung during the whole time of the siege a red banner with the letters painted in white: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.”

(4) Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927)

The members of the I.L.P., of which there was a good branch in Hammersmith, were very helpful, both as speakers and organisers during these meetings, but the Members of the Social Democratic Federation, of which I was a member, were very scornful because they said we should have been asking at that moment for Adult Suffrage and not Votes for Women; but although I have always been a staunch adult suffragist, I felt that at that moment the question of the enfranchisement of women was paramount, as we had to educate the public in our demands and in the reasons for our demands, and as we found that with many people the words “Adult Suffrage” connoted only manhood suffrage, our urgent duty was at that moment to gain Press publicity up and down the country and to popularise the idea of the political enfranchisement of women. So the siege wore on; Press notices describing it being sent to me not only from the United Kingdom, but from Continental and American newspapers, and though the garbled accounts of what I was doing and what our organisation stood for often made us laugh when we read them, still there was plenty of earnest and useful understanding in many articles, while shoals of letters came to me, a few sadly vulgar and revolting, but the majority helpful and encouraging. Some Lancashire lads who had heard me speaking in the Midlands wrote and said that if I wanted help they would come with their clogs but that was never the sort of support I needed, and though I thanked them, I declined the help as nicely as I could. Many Members of Parliament wrote and told me in effect that mine was the most logical demonstration that had so far been made; and it was logical I know as far as income tax paying women were concerned; and I explained in all my speeches and writings that though it looked as if I were only asking for Suffrage for Women on a property qualification, I was doing this because the mass of non-qualified women could not demonstrate in the same way, and I was to that extent their spokeswoman. It was the crude fact of women’s political disability that had to be forced on an ignorant and indifferent public, and it was not for any particular Bill or Measure or restriction that I was putting myself to this loss and inconvenience by refusing year after year to pay income tax, until forced to do so by the powers behind the Law. The working women from the East End came, time and again, to demonstrate in front of my barricaded house and understood this point and never swerved in their allegiance to our organisation; in fact, it was during these periods and succeeding years of work among the people that I realised more and more the splendid character and “stuff” that is to be found among the British working class. They are close to the realities of life, they are in daily danger of the serious hurts of life, unemployment, homelessness, poverty in its grimmest form, and constant misunderstanding by the privileged classes, yet they are mostly light-hearted and happy in small and cheap pleasures, always ready to help one another with lending money or apparel, great lovers of children, great lovers when they have an opportunity, of real beauty. Yet they are absolutely “unprivileged,” being herded in the “Ghetto” of the East End, and working and living under conditions of which most women in the West End have no idea; and I feel bound to put it on record that though I have never regretted, in fact, I have looked back on the years spent in the work of Woman Suffrage as privileged years, yet I feel very deeply that as far as those East End women are concerned, their housing and living conditions are no better now than when we began our work. The Parliamentary representation we struggled for has not been able to solve the Social Question, and until that is solved the still “unprivileged” voters can have no redress for the shameful conditions under which they are compelled to work and live.

I also have to record with sorrow that though some amelioration in the position of the married mother towards her child or children has been granted by law, the husband is still the only parent in law, and he can use that position if he chooses, to tyrannise over the wife. He must, however, appoint her as one of the guardians of his children after his death.

Towards the end of June, the time was approaching when, according to information brought in from outside the Crown had the power to break open my front door and seize my goods for distraint. I consulted with friends and we agreed that as this was a case of passive resistance, nothing could be done when that crisis came but allow the goods to be distrained without using violence on our part. When, therefore, at the end of those weeks the bailiff carried out his duties, he again moved what he considered sufficient goods to cover the debt and the sale was once again carried out at auction rooms in Hammersmith. A large number of sympathisers were present, but the force of twenty-two police which the Government considered necessary to protect the auctioneer during the proceedings was never required, because again we agreed that it was useless to resist force majeure when it came to technical violence on the part of, the authorities.

(5) Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927)

The next episode in this eventful year of unavoidable publicity in the women’s cause was the occasion in October, 1906, of our meeting as militant suffragists in the Lobby of the Houses of Parliament with the object of asking the Prime Minister to receive a deputation. It was agreed that if this request was refused several of us should get up on seats and make speeches for “Votes for Women.” Our request was refused, and we began to carry out our subsequent programme. Naturally after the first horror-struck moments of surprise at women daring to voice their wrongs in the very sanctuary of male exclusiveness, the uniformed guardians of the shrine rushed forward to cleanse the sacred spot from such pollution. The women speakers were dragged from their extemporised rostrums and were pushed down the galleries leading from the Lobby towards the Abbey entrance, and with little consideration were spurned down the steps on to the pavement. I was one of those thus ejected. My arm was twisted up against my back by a very strong-muscled policeman, and when I was released at the bottom of the steps of Westminster Hall, and had recovered from the pain of the operation, I turned round and watched the unwilling exit of crowds of other women. At a certain moment in the proceedings I saw Mrs. Despard standing at the top of the steps with a policeman just behind her, and fearing that a woman of her age might be injured by the rough-and-tumble methods which the police, under orders, were executing, I called out to some of the Members and onlookers who were mixed with us women at the foot of the stairs: “Can you men stand by and see a venerable woman handled in the way in which we have just been handled?” I was not allowed to say more, for Inspector Jarvis (who, however. I cannot fail to recall was on many occasions an excellent friend of mine, and who I know was in many respects in sympathy with much of our militant action), remarked to two constables standing near: “Take Mrs. Montefiore in; she is one of the ringleaders.” This “taking me in” meant marching me between two stalwart policemen to Cannon Row police station, where I was placed in a fairly large room and was soon joined by groups of excited and dishevelled militants. This was the beginning, in London, of a form of militancy which I always deprecated, the resistance to the police when being arrested, and struggles with police in the streets. I held that our demonstrations were necessary, and of great use in educating an apathetic public, but for women who are physically weaker than men to pit their strength against police who are trained in the use of physical violence, was derogatory to our sex and useless, if not a hindrance; to the cause for which we stood. When, therefore, some of my younger friends and fellow-workers were pushed into the waiting-room at Cannon Row, with their hair down and often with their clothing torn, I did my best to make them once more presentable, so that we should not appear in the streets as a dishevelled and very excited group of women. I held then, and have never ceased to hold the opinion, that even when demonstrating in the streets or when committing unconventional actions such as speaking in the Lobby of the House, we should always be able to control our voices and our actions and behave as ladies, and that we should gain much more support from the general public by carrying out this line of action. I should like to state here that I personally, except during the Lobby incident, never had to complain of the attitude of the police towards myself. In fact, I often found them helpful and sympathetic, as I shall have occasion later to relate.

After we had all been charged, and while stared at by special police, who were called in to identify us in case of future trouble, we were released on the understanding that we were to appear at the Westminster Court on the following morning. There we found that the charge against us was that of using “violent and abusive language.” Of course, every prisoner must be charged for some definite offence, and as the authorities could not discover that we had committed any of the definite offences in the criminal code, but had only begun to make speeches asking for votes for women, they put down the charge at random as that of “using violent and abusive language.” Each of us was asked in turn what we had to say in answer to the charge, and as I had with me the banner that had hung in front of my house during the “income tax siege,” I held it up first to the Magistrate and then for the Court to see. On it was inscribed: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” A constable snatched the banner from me and the proceedings continued. When the police, being asked for evidence of the breach of the laws which we had committed, were questioned definitely as to what they had heard, they each repeated that we had “asked for votes for women.” Their intellectual equipment was not equal to the task of repeating any of the arguments we had begun to unfold in the Lobby, but “Votes for Women” having by this time become a slogan, they were able to repeat that one sentence, though none of them looked particularly smart or happy as they did so. The proceedings were entirely farcical. The Magistrate consulted with others around him and tried to look very solemn and we were told that we were each to be bound over in the sum of £10 to keep the peace in future. This we all of us refused to do, as we did not consider we had broken the peace, or committed any offence for which we should be bound over. It was then explained to us that the alternative was two months’ imprisonment, and this alternative we accepted. We were once more taken from the Court and shut into a fair-sized room, where we were to be allowed to see friends and relatives, before being taken off to Holloway. As I, with the others, was leaving the Court, I said to the constable who was shepherding us, “I’m sorry to have lost that banner; it hung outside my house during the whole of the Hammersmith siege.” He grinned, but did not appear to be unfriendly, and as we filed into the room within the precincts of the Court, where we had to await “Black Maria,” he pushed the banner into my hands, and said: “It’s all right; here’s your banner.” As my daughter was married and not at the moment in very good health, I did not wish to add to her sufferings on my behalf by sending a summons asking her to come and see me at the Court. My son was working in an engineering business at Rochester and I also wished to save him from more trouble than I realised he was bound to have on my behalf. My brothers and sisters were mostly apathetic about, or hostile to my militant work, so I determined to send for no one of my own relatives, but I was surrounded by many good friends and fellow-workers who had come to give us a word of cheer. Towards evening “Black Maria” arrived at the Court and we were driven off to Holloway. “Black Maria” is a somewhat springless vehicle divided into compartments, so each prisoner is separated, though it is possible to speak to the prisoners immediately around one. It is used for conveying night after night the sweepings of the streets in the shape of drunkards and prostitutes from the Courts where they have been convicted, to Holloway Gaol. It can therefore be understood that it is neither a desirable nor a wholesome vehicle in which to travel. On arrival at Holloway we were each placed in some sort of sentry boxes with seats, and the woman who acted as receiving wardress opened one door after another and took down the details connected with the charge, and the status of the prisoner. She was of decided Irish extraction and the questions she put to us each in succession were to this effect: “Now then, gurrl, stand up! What’s your name, what’s your age, how do you get your livin’?” etc. etc. When all these questions had been answered to the satisfaction of this lady, we were told to leave our compartments and stand in a passage, where we were ordered to strip to our chemises or combinations and then to await further orders. The next scene was taking down our hair and searching rather perfunctorily our heads for possible undesirable inhabitants, after which a prison chemise, made of a sort of sacking, and generously stamped with the broad arrow, was handed to each of us, and I found myself exchanging my warm wool and silk combinations for this decidedly chilly and ungainly garment. The bath ordeal was not serious; we had only to stand in a few inches of doubtful-looking warm water and then put on the various articles of prison clothing provided for us. Each of us had a flannel petticoat made with enormous pleats round the waist, a dress of green serge made on the same ample lines and an apron, a check duster, which we were told was the handkerchief supplied, and a small green cape made with a hood, for out-door exercise, and a white linen cap tied under the chin. Thus arrayed our little party consisting of Mrs. How Martyn, Miss Irene Miller, Miss Billington, Miss Gauthorp, Mrs. Baldock, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence, Miss Annie Kenney, Miss Adela Pankhurst, Mrs. Cobden Saunderson and myself, met in one of the passages where our yellow badges bearing the numbers under which we were each to be known while in prison were handed out to us. We then underwent another and more detailed interrogatory, in which came the question: “What religion?” When I replied “Freethinker,” the wardress remarked “Free-what?” “That is no religion, you will be Protestant as long as you remain here”; and part of my description card fastened outside my cell contained the word “Prot.” We were then shut up in our respective cells with a cup of cocoa and a piece of bread and left for the night.

Much was written at the time about Holloway and the conditions under which prisoners lived during the time they were working out their sentences, and as I believe that something has been done to improve conditions since we militants made our protest by allowing ourselves to be imprisoned there, I want to put on record quite dispassionately and as of historical interest the sort of cells and the sort of surroundings accorded to women prisoners in October, 1906.

The cells had a cement floor, whitewashed walls and a window high up so that one could not see out of it. It was barred outside and the glass was corrugated so that one could not even get a glimpse of the sky; and the only sign of outside life was the occasional flicker of the shadow of a bird as it flew outside across the window. The furnishing of the cell consisted of a wooden plank bed stood up against the wall, a mattress rolled up in one corner, two or three tin vessels, a cloth for cleaning and polishing and some bath brick. On the shelf were a Bible, a wooden spoon, a salt cellar, and one other book whose name I forget, but I remember glancing into it and thinking it would appeal to the intelligence of a child of eight. There was also a stool without a back, and inside the mattress when unrolled for the night and placed on the wooden stretcher were two thin blankets, a pillow and some rather soiled-looking sheets. One tin utensil was for holding water, the second for sanitary purposes, and the third was a small tin mug for holding cocoa. A bell was rung early in the morning for us to get up, when our cell doors were unlocked and were left open while we emptied slops and cleaned out our cells. I may mention in passing that only one cloth was provided for cleaning the sanitary tin pail, the water container and the tin mug, and these all had to be polished with bath-brick, and placed in certain positions in readiness for cell inspection. Breakfast consisted of cocoa and a good-sized hunk of brown bread (excellent in quality), but what was called cocoa turned black in the tin mug and I could not drink it, so I breakfasted every day on brown bread and cold water. After breakfast came cell inspection, attendance at Church, exercise in the prison yard and visits from the schoolmistress, padre or parson. The service in the Protestant Church which I had to attend was rather a pitiful function, for one then could see the faces of the hundreds of derelict women with whom one was hounded. The majority were women who passed more of their life in prison, than outside it; they had evidently lost what little will-power they may once have had, but uncontrolled emotion still remained and when a hymn that appeal to them was sung, their poor faces would twitch spontaneously, the tears would roll down their cheeks and they would rock back and forth in their seats. A few young women were there, looking mostly hard and brazen and one could not help speculating if, under present social conditions, they would not in thirty or forty years’ time become hardened criminals such as the elder women I saw around. In the course of the first morning the door of my cell was flung open by the wardress who announced: “Roman Catholic Chaplain, stand up!” I looked round from my seat to see a pleasant-faced young Catholic priest, who held in his hand some newspaper cuttings. “This is only an informal visit,” he announced with a smile, “I thought you might like to see some of the newspaper cuttings and pictures about yourself, so I am visiting you and your friends to show them and to have a chat. This was the first intimation I had had that anybody in Holloway recognised the particular conditions under which we had been arrested and brought here. We were treated by all the wardresses as if we were ordinary prisoners such as the thieves and prostitutes with whom we were surrounded. But this Roman Catholic Padre had a very human streak in his composition and he not only understood, but he wished us to realise that he understood that we were fighting for an ideal, and that this acceptance of the conditions of ordinary imprisonment was part of the unpleasantness of the fight in which we were engaged. The Protestant parson I found much less understanding, and as he really bored me, I let him understand that his visits were not altogether acceptable. On the second morning of prison life the wardress flung open the door of the cell announcing: “Schoolmistress, stand up!” I never took any notice of this last injunction, but used to peep round the corner to see who was coming in. A pleasant-faced woman appeared who stood in the doorway and asked: “Can you read and write?” A devil of mischief took hold of me and I replied almost shamefacedly and in a low voice: “A little.” “Because if not,” she went on briskly, “you can attend the school classes every day for an hour.” “Oh,” I replied with rather more interest, “should I be allowed to teach in the school? I can do that much better than sewing these sacks which I do not know how to do and which are making my hands quite sore.” “No,” she replied, “during the first month of a prisoner’s time she is not allowed to work outside her cell at anything.” This crushed my hopes in the schoolroom direction and I had to return to the making of mail bags, which I believe are made with jute and are certainly sewn with very large needles and with wax thread. I got through my tasks in this direction very slowly and often had to work at night, when otherwise I might have had a chance of reading.

The prison clothing granted by King Edward VII for the use of prisoners during their sojourn at Holloway was, I found, lacking in half sizes, or perhaps, also in outsizes. The skirt of my dress, though it would be quite fashionable nowadays, was unfashionable in 1906, because it reached barely below my knees, and the stockings provided were of the quality worn by schoolboys and boy scouts, and they reached barely to my knees also. As no garters or suspenders were allowed, the problem I found for me and for other imprisoned suffragists was how to keep these stockings up while we marched in single file round and round the prison yard. I used to make continual vicious grabs at these detestable stockings, but unfortunately these stoppages to give a grab broke up the regularity of the march and the wardress in charge would shout: “Now, then, number …. keep up with the rest.” On a wet morning the yard would have little pools and puddles all over it, and as my stockings slipped down over my ankles they would become wet and muddy and even more difficult to control; so at last I gave the whole matter up as a bad job and marched round the yard “under bare poles.” Irene Miller, who saw and sympathised with my difficulties, whispered to me as we passed in from the prison yard returning to our cells: “Cheer up, I am knitting in my cell and I will knit you a pair of garters.” This she did, and passed them to me the next morning whilst we were cleaning our cells.