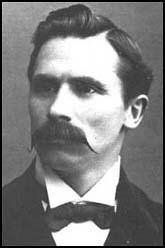

Tom Mann

Tom Mann, the son of the clerk at the local colliery, was born in Foleshill, near Coventry, on 15th April, 1856. Tom started school at six but left at nine to work at a farm. The following year he became a trapper at the Victoria Colliery. A series of underground explosions closed the colliery and in 1870 the family moved to Birmingham and Tom started a seven-year engineering apprenticeship.

Tom was a religious boy and on a Sunday he would sample different church services. He considered joining the Nonconformist and Quaker groups before becoming a teacher at the local Anglican Sunday School. Tom also attended a large number of political meetings and heard people such as John Bright, George Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant speak in Birmingham.

After Tom Mann finished his apprenticeship in 1877 he moved to London. Unable to find work in his trade, Mann did a variety of different menial jobs before being employed in an engineering shop in 1879. Mann's foreman, Sam Mainwaring, was a socialist and introduced him to the ideas of William Morris. Mann became interested in improving his education over the next few years spent his leisure time reading writers such as John Stuart Mill, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin and Henry George.

In 1881 Mann joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and soon afterwards participated in his first strike. He also became a member of the Fabian Society and the Battersea branch of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) that had just been established by John Burns.

Mann was a strong advocate of the eight-hour day, one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Federation, Henry Hyde Champion, suggested that he should write a pamphlet on the subject. The pamphlet, What a Compulsory Eight-Hour Day Means to the Workers, was published in June, 1886, and helped to persuade a large number of people to support this measure. Mann formed the Eight Hour League and this group was influential in convincing the trade union movement to adopt the statutory eight-hour day as one of its core policies.

Mann read The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1886. Mann was converted and after this date he openly admitted to being a communist. He now saw the main purpose of trade union activity was to try and bring about the overthrow of the capitalist system.

In 1887 Tom Mann moved to Newcastle where he became the SDF's northern organizer. While in the area he helped form the North of England Socialist Federation. He also acted as the manager of the campaign to get Keir Hardie elected as MP for Mid-Lanarkshire. After this he returned to London and worked as an investigative journalist for the Labour Elector, a journal edited by Henry Hyde Champion.

When the London Dock Strike started in August 1889, Ben Tillett asked Mann to manage the distribution of relief tickets to his union members. Tillett's union was demanding four hours continuous work at a time and a minimum rate of sixpence an hour. During the dispute Mann emerged with Tillett and John Burns as one of the three main leaders of the strike.

The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but other trade union activists such as Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and Henry Hyde Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands.

After the successful strike, the dockers formed a new General Labourers' Union. Ben Tillett was elected General Secretary and Tom Mann became the union's first President. In London alone, 20,000 men joined this new union. Tillett and Mann wrote a pamphlet together called the New Unionism, where they outlined their socialist views and explained how their ideal was a "cooperative commonwealth".

Mann was now one of England's leading trade unionists. He was elected to the London Trades Council, became secretary of the National Reform Union, and a member of the Royal Commission on Labour (1891-93). He remained a strong supporter of Christian Socialism and in 1893 considered the possibility of becoming an Anglican minister.

In 1894 Mann was elected as secretary of the new Independent Labour Party (ILP). He stood three times for Parliament as a ILP candidate. He was defeated in the 1895 General Election at Colne Valley and at a by-election in North Aberdeen in the following year, he came within 500 votes of victory. A third attempt at a by-election in Halifax in 1897 also ended in failure.

Mann remained an active trade unionist and in 1897 he helped form the Workers Union and although growth was initially slow, it and eventually merged with others to became the Transport & General Workers Union.

In December, 1901, Mann emigrated to Melbourne in Australia. He was active in both trade unionism and politics. He became an organizer for the Australian Labour Party and in 1910 formed the Socialist Party of Australia. He was arrested twice and charged with sedition but in both cases was acquitted.

Mann returned to England in 1910 and his old friend Ben Tillett, employed him as an organizer for his Dockers Union. Mann also wrote a pamphlet, The Way to Win, where he argued that socialism would be achieved through trade union activity rather than by parliamentary elections. He established the Industrial Syndicalist Education League and edited The Industrial Syndicalist.

Tom Mann led the 1911 transport workers strike in Liverpool, and although it lasted for seventy-two days, the employers eventually accepted the union's demands. During the strike Mann published a leaflet written by a railwayman, Fred Crowsley, urging soldiers not to fire upon striking workers. After the strike was over Mann was arrested and charged with sedition. He was found guilty and sentenced to six months imprisonment but only served seven weeks before public pressure secured his release.

Like many socialists, Mann was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. He joined the British Socialist Party, an organisation hostile to the war and in 1917 supported the Russian Revolution and suggested the creation of soviets in Britain.

Tom Mann was elected to the post as Secretary of the Amalgamated Engineering Union in 1919 but two years later was forced to resign as he had reached sixty-five, the compulsory retirement age.

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF).

It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Early members included Tom Mann, Tom Bell, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, Rose Cohen, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart, Shapurji Saklatvala, Sylvia Pankhurst and Robin Page Arnot.

Mann continued to travel the world advocating socialism and published pamphlets such as Russia in 1921, where he supported the measures being taken by the Russian communist government. In 1923 he published his autobiography, Tom Mann's Memoirs.

Mann, now in his late seventies, continued to upset the authorities with his speeches and pamphlets. After a speech he made in Belfast in October 1932 criticizing cuts in poor relief, he was sent to prison under the terms of the 1817 Seditious Meetings Act. Two years later he was put on trial in Cardiff for sedition but was acquitted.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Mann became a member of the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, an organization that had been set-up by the Socialist Medical Association and other progressive groups. Other members included Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, Ben Tillett, Harry Pollitt, Hugh O'Donnell, Mary Redfern Davies and Isobel Brown.

In August 1936 Harry Pollitt arranged for Tom Wintringham to go to Spain to represent the Communist Party of Great Britain during the Civil War. While in Barcelona he developed the idea of a volunteer international legion to fight on the side of the Republican Army. He wrote: "You have to treat the building of an army as a political problem, a question of propaganda, of ideas soaking in." Pollitt agreed and it was decided to call it the Tom Mann Centuria and it was one of the first of the International Brigades that fought in the war.

Tom Mann died in Leeds on 13th March, 1941.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

I had only a very short time at school as a boy, less than three years all told. When I was nine years old I was considered old enough to start work. My father was a clerk at the Victoria Colliery; so it was counted fitting that I should make a start as a boy on the colliery farm. A year as a kiddie doing odd jobs in the fields, bird-scaring, leading the horse at the plough, stone-picking, harvesting, and so on, and I was to tackle a job down the mine.

My job was to make and keep in order small roads or courses to convey the air to the respective workings in the mines. The air courses were only three feet high and wide, and my work was to take away the mullock, coal, or dirt that the man would require taken from him as he was worked away at 'heading' a new road, or repairing an existing one.

For this removal there were boxes known down the mine as dans, about two feet six inches long and eighteen inches wide and of a similar depth, with an iron ring strongly fixed at each end. A piece of stout material was fitted on the boy around the waist. To this there was a chain attached, and the boy would hook the chain to the box, and crawling on all fours, the chain between his legs, would drag the box along and take it to the gob where it would be emptied.

(2) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

Although I was connected with the Anglican Church, the Bible class I attended and liked so much was conducted by Edmund Laundy of the Society of Friends. Mr. Laundy was a public accountant, a precise speaker, a splendid teacher. He taught me much, and helped me in the matter of correct pronunciation, clear articulation, and insistence upon knowing the root origin of words, with a proper care in the use in the right words to convey ideas.

(3) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

In 1884 I joined the Battersea branch of the Social Democratic Federation. It held meetings every Sunday morning in the open air, at Battersea Park gates, on Sunday morning in the open air, on Sunday evenings in Sydney Hall, and at various other places during the week. John Burns was the foremost member of the branch, and had already won renown as a public advocate of the new movement. I threw myself into the movement with all the energy at my command.

(4) n his book, Memories and Reflections, the trade union leader, Ben Tillett described meeting Tom Mann for the first time in 1889.

He (Tom Mann) combined the qualities of whirlwind and volcano. His was the genius of sheer energy. His tremendous capacity for the work he enjoys the most became a mighty factor in the supreme crisis of the Dock Strike. For Tom Mann I entertain a deep respect as a comrade which has not been destroyed by the intellectual vagrancy into which his energy led him in after years. I remember old Henry Hyndman saying that Tom's intellect was a tidal one, swayed by changes in the moon, and capable of the same ebb and flow. Still, he has been a consistent class-conscious fighter for the various causes to which he has adhered; sound at heart, self-sacrificing and courageous, he has never deserted the flag, even if he has sometimes attempted to plant it in impossible places.

(5) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

In the early days of the Independent Labour Party Tom Mann became General Secretary of the party. He was at that time a well-known figure in the Labour movement. He had come into prominence in connection with the Dockers' Strike. He was the most volcanic speaker I have known, and a man of marvellous physical vigour. If Tom Mann had possessed one thing he lacked, namely, steadfastness of purpose, he would have been undoubtedly one of the most prominent men in the Labour Party of today. But he never could remain long associated with one movement. He had not the gift of settling down to one job and pursuing it to success. He was one of the most charming men personally I have known, kind-hearted and generous and tolerant. I never heard him speak an unkind word of anyone.

(6) In his book, Memories and Reflections, the trade union leader, Ben Tillett described the work that Tom Mann did for the Dockers' Strike in 1889.

I placed Tom Mann in charge of the difficult duty of seeing that the system of relief was systematically organised. The strikers, I might even say the dockers in general, involved in the stoppage of work, were recipients of relief. They were all desperately in need and when it was announced that relief tickets were to be distributed some thousands of them gathered before the door of the dingy little coffee tavern where Tom Mann and his helpers, having just received the relief tickets from the printers, were preparing to issue them.

(7) Charlie Glyde, Thirty Years' Reminiscences (1923)

Tom Mann was invited by the SDF to come to Bolton as organizer. A shop in one of the main streets was stocked with tobacco, newspapers, etc., and he was installed as manager. Tom drew very large crowds to the Town Hall Square. Street corner and propaganda meetings were held in the surrounding towns and villages. his fiery speeches were marvels of eloquence and power. Tom Mann was well grounded in socialism and economics. He was one of the best speakers I have known. Of medium height, well built, with black hair, and with the first word uttered he gripped his audience and kept them spell-bound until the end.

(8) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

My close friendship at this period with various ministers of religion led to the circulation of a report that I was about to enter the Church. One morning a pressman called upon me to ask what truth there was in the statement that appeared in The Times on 5th October, 1893. I contradicted the statement that matters were arranged, but did not deny that the subject had been under serious consideration.

(9) Fred Crowsley, Open Letter to British Soldiers (1911)

"Thou shalt not kill," says the Bible. Don't forget that! It does not say, "unless you have a uniform on". No! Murder is murder, whether committed in the heat of anger on one who has wronged a loved one, or by clay-piped Tommies with a rifle.

Don't disgrace your parents, your class, by being the willing tools any longer of the master class. You, like us, are of the slave class. When we rise, you rise. When we fall, even by your bullets, you fall also.

(10) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

Trade unionism is of no value unless the members of the unions are clear as to their objective - the overthrow of the capitalist system - and are prepared to use the unions for that purpose. Political action is of no value unless all political effort is used definitely and avowedly for the same end, the abolition of the profit-making system.

As far back as 1886, I took an active part in celebrating the Commune of 1871, and have continued to participate in the anniversary celebration down to the present time. I gladly accepted the name of Communist from the date of my first reading of The Communist Manifesto, and have ever since been favourable to Communist ideals and principles.

(11) Beatrice Potter heard Tom Mann make a speech on 19th November, 1889, at Toynbee Hall.

Tom Mann is a fine fellow, absolutely straight and a warm enthusiast. He opened his speech by reference to Co-operation. Socialism means the Co-operative organization of industry when no one shall be outside. This was the ideal state towards which they were all striving. He went on to argue that the only method of reducing the great army of unemployed was to reduce the hours of the workers so as to divide the employment among all persons in the trade.

(12) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (23rd January, 1895)

Last night we had an informal conference with the ILP leaders. Ramsay MacDonald and Frank Smith (who are members both of the Fabians and the ILP) have been for some time harping on the desirability of an understanding between the two societies. To satisfy them Sidney (Webb) arranged a little dinner of Keir Hardie, Tom Mann, Edward Pease and George Bernard Shaw and the two intermediaries. I think the principals on either side felt it would come to nothing. Nevertheless, it was interesting.

Tom Mann said the Progressives on the LCC were not convinced Socialists. No one should get the votes of the ILP who did not pledge himself to the 'Nationalisation of the Means of Production'. Keir Hardie, who impressed me very unfavourably, deliberately chooses this policy as the only one which he can boss. His only chance of leadership lies in the creation of an organisation "against the government"; he knows little and cares less for any constructive thought or action. But with Tom Mann it is different. he is possessed with the idea of a 'church' - of a body of men all professing exactly the same creed and all working in exact uniformity to exactly the same end. No idea which is not 'absolute', which admits of any compromise or qualification, no adhesion which is tempered with doubt, has the slightest attraction to him. And, as Shaw remarked, he is deteriorating. This stumping the country, talking abstractions and raving emotions, is not good for a man's judgment, and the perpetual excitement leads, among other things, to too much whisky.

I do not think the conference ended in any understanding. We made clear our position. We were a purely educational body, we did not seek to become a 'party'. We should continue our policy of inoculation, of giving to each class, to each person, that came under our influence the exact dose of collectivism that they were prepared to assimilate.

(13) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

It had become evident that the only thing for me to do was to go to London and explain the whole position to the Committee. Every one of us in Grañen approved of this visit as also did the Committee itself. When I arrived in London I found everyone entirely helpful and understanding. Getting the members to accept that "their" Unit should become a part of the Spanish Republican Army was not at first easy, but I was very well seconded by that great pioneer Trade Unionist Ben Tillet.

He cannot have been far from 80 years old and, to use his own words, he was roaring "to have a crack at the bastards". He drank well in the National Trade Union Club where the Committee had its offices and he sometimes dozed in meetings. He was a Popular Front adherent but showed a reserve towards the Communist Party because he had once kept a Public House in partnership with Tom Mann. By 1936 Tom Mann was a revered CP pioneer whose name was to be given to a British Company in the International Brigade. Ben Tillet did not like this at all. "It won't do; it can't be done. Tom Mann was prosecuted for watering beer. It was under gravity, all behind my back, no one can trust a man who waters the beer.”

Ben Tillet always had a refreshing influence. Once, when I was sitting next to Eilleen Younghusband (Independent MP for the British Universities seat), Franco's name had just been mentioned. Ben woke up from a cat-nap. He was alert in an instant and, before closing his eyes again, loudly proclaimed, "Franco's Mussolini's ponce that's what he is, nothing more than a ponce." Miss Younghusband, Quakerish and liberal spinster, was very taken by this intervention. She whispered to me, "What a splendid word, I must use it, but perhaps I should first know what it means."