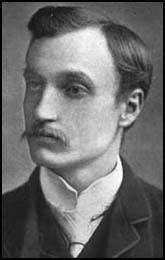

Ben Tillett

Ben Tillett, the son of a labourer, was born in Bristol in 1860. His mother died when he was a child and a succession of step-mothers treated him very badly. He ran away from home as a child and found work as an acrobat in a circus.

Tillett also worked as a shoemaker but at the age of thirteen he joined the Royal Navy. In 1876 he was wounded and invalided out of the service.

Tillet moved to London after after marrying Jane Tompkins he settled down in Bethnal Green. He found a job as a shoemaker but after he was made redundant he found work in the London Docks. He eventually became a teacooper at the Monument Tea Warehouse.

It was during this period he became a Christian Socialist. He attended the local Congregational Church and joined the Temperance Society. Tillet attended evening classes and despite a speech impediment, developed an ambition to become a barrister. Tillet joined the Tea Operatives & General Labourers' Association. Tillett was very vocal at meetings and in 1887 he was elected to the post of General Secretary.

The following year Tillett led a strike at Tilbury Dock. The workers were defeated and Tillett became so depressed that he considered leaving the union. He campaigned for the post as General Secretary of the Gasworkers' Union but he was defeated by Will Thorne.

In 1889 Tillet's union members became involved in the London Dock Strike. The dockers demanded four hours continuous work at a time and a minimum rate of sixpence an hour. Tillet soon emerged with Tom Mann and John Burns as one of the three main leaders of the strike. During the strike Tillett lost his speech impediment and was acknowledged as one of the labour movement's greatest orators.

The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but other trade union activists such as Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and H. H. Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands.

After the successful strike, the dockers formed a new General Labourers' Union. Tillett was elected General Secretary and Tom Mann became the union's first President. In London alone, 20,000 men joined this new union. Tillett and Mann wrote a pamphlet together called the New Unionism, where they outlined their socialist views and explained how their ideal was a "cooperative commonwealth".

Tillett was now one of England's leading socialists. He was a member of the Fabian Society and was one of the founders of the Independent Labour Party. In the 1892 General Election he was the the ILP's candidate in Bradford and only lost to the Liberal Party candidate by 500 votes.

Tillet was one of the founders of the Labour Party but did not get on with its two main leaders, James Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald. In 1908 he attacked the leadership in his pamphlet Is the Parliamentary Labour Party a Failure? and soon afterwards left to join the Social Democratic Party.

In September 1910 Tillett helped to establish the National Transport Workers' Federation, an organisation of 250,000 workers. He became the leader of the union and in 1911 it won a national strike. However, the following year, Tillett's union suffered a defeat at the hands of the Port of London Authority. It was during this strike that Tillet joined with George Lansbury and Will Dyson to form the trade union newspaper, the Daily Herald.

Unlike many socialist, Ben Tillett fully supported Britain's involvement in the First World War. His enthusiasm for aerial bombardment of German civilian centres and his views that pacifists should be severely punished, made him unpopular with many people in the labour movement. Tillett travelled throughout Britain and helped to recruit a large number of industrial workers into the armed forces.

In 1917 Ben Tillett stood as an Independent candidate in a by-election at North Salford. During the campaign he attacked the Labour Party for its internationalist views. With the strong anti-German feeling at the time, Tillett had little difficulty winning the seat.

In the 1918 General Election Tillett stood as the Labour Party candidate in North Salford. However, his views were now very conservative and was unable to obtain a senior position in the parliamentary party. Tillett wanted to become General Secretary of the new Transport and General Workers Union but he had little support and he decided not to stand for the post.

Tillett retired from the House of Commons in 1931. Except for an attempt to organize a boxer's union in 1932, he ceased to be active in the labour movement.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Tillett became a member of the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, an organization that had been set-up by the Socialist Medical Association and other progressive groups. Other members included Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Mann, Harry Pollitt, Hugh O'Donnell, Mary Redfern Davies and Isobel Brown.

Ben Tillett died on 27th January, 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Ben Tillett, Memories and Reflections (1931)

I was the youngest of eight children. My brave little mother, fighting a hopeless battle, died when I was just over a year old. her mothering, the slavery of her devotion to her family, her endless services to others killed her. She came of gentle Irish stock, and was devoutly religious, but the drudgery of her life, hunger, pain, and suffering destroyed her body, though there was flame in her soul to the end.

(2) Ben Tillett, Memories and Reflections (1931)

Trade Unionism (in 1889) substantially affected only the minority of workers. Of the twelve millions of earners, he said, certainly not one million were in Unions. In one or two of the most skilled trades that unionists were perhaps in the majority. Existing Unions were those of craftsmen, relatively well paid, and their organizations were correspondingly wealthy - and well organised.

(3) Ben Tillett, Memories and Reflections (1931)

As a docker I had tried to save money, and starved to buy books. I was struggling to learn Latin, and even trying to study Greek, lending my head and aching body to the task after my day's work on the dockside, or in the tea warehouse where I was employed - work which meant carrying tons on my back up and down flights of stairs.

(4) Ben Tillett, speech made at a meeting of the Tea Coopers and General Labourers' Union (27th July, 1887)

There is nothing refining in the thought that to obtain employment we are driven into a shed iron-barred from end to end, outside of which a contractor or a foreman walks up and down with an air of a dealer in a cattle market, picking and choosing from a crowd of men who in their eagerness to obtain employment, trample each other underfoot, and where like beasts they fight for the chances of a day's work. To remedy this condition of affairs we have formed the Tea Coopers and General Labourers' Association.

(5) In his book, Memories and Reflections, Ben Tillett describes meeting Tom Mann for the first time in 1889.

He combined the qualities of whirlwind and volcano. His was the genius of sheer energy. His tremendous capacity for the work he enjoys the most became a mighty factor in the supreme crisis of the Dock Strike. For Tom Mann I entertain a deep respect as a comrade which has not been destroyed by the intellectual vagrancy into which his energy led him in after years. I remember old Henry Hyndman saying that Tom's intellect was a tidal one, swayed by changes in the moon, and capable of the same ebb and flow. Still, he has been a consistent class-conscious fighter for the various causes to which he has adhered; sound at heart, self-sacrificing and courageous, he has never deserted the flag, even if he has sometimes attempted to plant it in impossible places.

(6) In his book, Memories and Reflections, Ben Tillett recalled how they raised money during Dockers' Strike of 1889.

In our marches we collected contributions in pennies, sixpences and shillings, from the clerks and City workers, who were touched perhaps to the point of sacrifice by the emblem of poverty and starvation carried in our procession. By these means, with the aid of the Press, money poured into our coffers from Trade Unions and public alike. Large sums came from abroad, especially from the British dominions, whose contributions alone amounted to over £30,000. Contributions from the public sent direct by letter or collected on our marches totalled nearly £12,000; more than £1,000 came in from our street box collections, and substantial amounts were obtained through the help of the star, the Pall Mall Gazette, the Labour Elector, and other papers.

(7) In his book, Memories and Reflections, Ben Tillett describes the work that Cardinal Manning did for the Dockers' Strike in 1889.

From the first Cardinal Manning showed himself to be the dockers' friend, though he had family connections in the shipping interests, represented on the other side. Our demands were too reasonable, too moderate, to be set aside by an intelligence so fine, a spirit so lofty, as that which animated the frail, tall figure with its saintly, emaciated face, and the strangely compelling eyes.

On our side there was no margin for concession. We had made no extravagant demands. The Cardinal's diplomacy, suave, subtle, ineffably courteous to all parties concerned, yet exercised with the suggestion of authority. He endorsed with a sense of responsibility the two main claims of the dockers for the 6d. minimum, and recognition of the Union.

(8) Ben Tillett, Memories and Reflections (1931)

I can fairly claim to have played an active part in the development of the political Labour Movement. I was present at the Trades Union Congress in 1899 when adopted the historic resolution instructing its Parliamentary Committee to invite the co-operation of all Socialistic, Co-operative, Trade Union, and other working-class organisations in a joint effort to establish at a special Congress an effective political organisation for the workers. At the special Conference on Labour Representation held at the Memorial Hall in London, in obedience to this resolution early in 1900, I was a delegate on behalf of my Society and made by voive heard in the debate on the resolution proposing the formation of the distinct Labour Group in Parliament and other aspects of the policy to be pursued.

(9) Ben Tillett described work as a London docker at the end of the 19th century in his book A Brief History of the Dockers Union (1910)

We are driven into a shed, iron-barred from end to end, outside of which a foreman or contractor walks up and down with the air of a dealer in a cattlemarket, picking and choosing from a crowd of men, who, in their eagerness to obtain employment, trample each other under foot, and where like beasts they fight for the chances of a day's work.

(10) In his book, Memories and Reflections, Ben Tillett described his relationship with Lord Rosebery, chairman of the London County Council.

My experience on the London County Council brought me into contact with its distinguished chairman, Lord Rosebery. He was one of our great men, in spite of being an aristocrat. What gifts of oratory, of tongue and pen alike, he possessed! A man of outstanding culture, he was the embodiment of a tradition that made him distinguished even when physical proportions lent no imposing presence. One may talk of breeding, culture, and patter the language of the obsequious, but one can scarcely say too much of Lord Rosebery.

(11) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

Ben Tillett, general secretary of the Tea Operatives' and General Labourers' Union, would pour forth invectives upon all opponents, would reach the heart's core of the dockers by his description of the way in which they had to beg for work and the paltry pittance they received, and by his homely illustrations of their life as it was and as it should be. He was short in stature, but tough; pallid, but dauntless; affected with a stammer at this time, but the real orator of the group.

(12) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

It had become evident that the only thing for me to do was to go to London and explain the whole position to the Committee. Every one of us in Grañen approved of this visit as also did the Committee itself. When I arrived in London I found everyone entirely helpful and understanding. Getting the members to accept that "their" Unit should become a part of the Spanish Republican Army was not at first easy, but I was very well seconded by that great pioneer Trade Unionist Ben Tillet.

He cannot have been far from 80 years old and, to use his own words, he was roaring "to have a crack at the bastards". He drank well in the National Trade Union Club where the Committee had its offices and he sometimes dozed in meetings. He was a Popular Front adherent but showed a reserve towards the Communist Party because he had once kept a Public House in partnership with Tom Mann. By 1936 Tom Mann was a revered CP pioneer whose name was to be given to a British Company in the International Brigade. Ben Tillet did not like this at all. "It won't do; it can't be done. Tom Mann was prosecuted for watering beer. It was under gravity, all behind my back, no one can trust a man who waters the beer.”

Ben Tillet always had a refreshing influence. Once, when I was sitting next to Eilleen Younghusband (Independent MP for the British Universities seat), Franco's name had just been mentioned. Ben woke up from a cat-nap. He was alert in an instant and, before closing his eyes again, loudly proclaimed, "Franco's Mussolini's ponce that's what he is, nothing more than a ponce." Miss Younghusband, Quakerish and liberal spinster, was very taken by this intervention. She whispered to me, "What a splendid word, I must use it, but perhaps I should first know what it means."