The Fabian Society

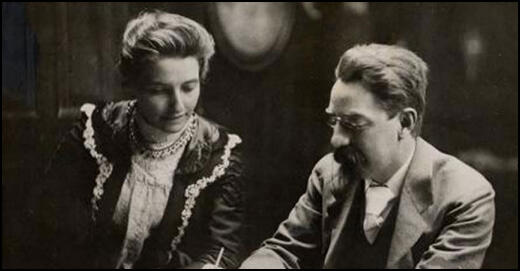

In October 1883 Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland decided to form a socialist debating group with their Quaker friend Edward Pease. They were also joined by Havelock Ellis and Frank Podmore and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles.

Hubert Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. By March 1884 the group had twenty members. In April 1884 Edith Nesbit wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

George Bernard Shaw joined the Fabian Society in August 1884. Nesbit wrote: "The Fabian Society is getting rather large now and includes some very nice people, of whom Mr. Stapelton is the nicest and a certain George Bernard Shaw the most interesting. G.B.S. has a fund of dry Irish humour that is simply irresistible. He is a clever writer and speaker - is the grossest flatterer I ever met, is horribly untrustworthy as he repeats everything he hears, and does not always stick to the truth, and is very plain like a long corpse with dead white face - sandy sleek hair, and a loathsome small straggly beard, and yet is one of the most fascinating men I ever met."

Over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Edith Lees, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Charles Trevelyan, John Clifford, Arthur Ransome, Cecil Chesterton, Ada Chesterton, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Edward Carpenter, Clement Attlee, Ramsay MacDonald, Emmeline Pankhurst,Walter Crane, Arnold Bennett, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Hugh Dalton, C. E. M. Joad, Rupert Brooke, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

Early talks at the Fabian Society included: How Can We Nationalise Accumulated Wealth by Annie Besant, Private Property by Edward Carpenter, The Economics of a Postivist Community by Sidney Webb and Personal Duty under the Present System by Graham Wallas.

In 1886 Frank Podmore and Sidney Webb carried out an investigation into unemployment. In the Fabian Society pamphlet, The Government Organisation of Unemployed Labour they advocated the funding of rural land armies but declined to endorse large-scale public employment as they feared it would encourage inefficiency.

By 1886 the Fabians had sixty-seven members and an income of £35 19s. The official headquarters of the organisation was 14 Dean's Yard, Westminster, the home of Frank Podmore. The Fabian Society journal, Today, was edited by Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland.

The Fabians believed that capitalism had created an unjust and inefficient society. They agreed that the ultimate aim of the group should be to reconstruct "society in accordance with the highest moral possibilities". The Fabians rejected the revolutionary socialism of H. M. Hyndman and the Social Democratic Federation and were concerned with helping society to move to a socialist society "as painless and effective as possible".

The Fabians adopted the tactic of trying to convince people by "rational factual socialist argument", rather than the "emotional rhetoric and street brawls" of the Social Democratic Federation. The Fabian group was a "fact-finding and fact-dispensing body" and they produced a series of pamphlets on a wide variety of different social issues.

In 1889 the Fabian Group decided to publish a book that would provide a comprehensive account of the organisations's beliefs. Fabian Essays in Socialism included chapters written by George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Webb, Annie Besant, Sydney Olivier, Graham Wallas, William Clarke and Hubert Bland. Edited by Shaw, the book sold 27,000 copies in two years.

William Morris, a former member of the Social Democratic Federation, and founder of the Socialist League, strongly criticised the Fabian Essays in the journal Commonweal. Morris disagreed with what he called "the fantastic and unreal tactic" of permeation which "could not be carried out in practice, and which, if it could be, would still leave us in a position from which we should have to begin our attack on capitalism over again".

The success of Fabian Essays in Socialism (1889) convinced the Fabian Society that they needed a full-time employee. In 1890 Edward Pease was appointed as Secretary of the Society. His duties included keeping the minutes at meetings, dealing with the correspondence, arranging lecture schedules, managing the Fabian Information Bureau, circulating book-boxes and editing and contributing to the Fabian News.

In 1890 Henry Hutchinson, a wealthy solicitor from Derby, decided to give the Fabian Society £200 a year to spend on public lectures. Some of this was used to pay Fabian members such as Harry Snell, Ramsay MacDonald, Graham Wallas, Catherine Glasier and Bruce Glasier to travel around the country giving lecturers on subjects such as 'Socialism', 'Trade Unionism', 'Co-operation' and 'Economic History'.

Hutchinson died four years later leaving the Fabian Society £10,000. Hutchinson left instructions that the money should be used for "propaganda and socialism". Hutchinson selected his daughter as well as Edward Pease, Sidney Webb, William Clarke and W. S. De Mattos as trustees of the fund, and together they decided the money should be used to develop a new university in London. The London School of Economics (LSE) was founded in 1895. As Sidney Webb pointed out, the intention of the institution was to "teach political economy on more modern and more socialist lines than those on which it had been taught hitherto, and to serve at the same time as a school of higher commercial education".

The Webbs first approached Graham Wallas, now one of the most prominent members of the Fabians, to become the Director of the LSE. Wallas agreed to lecture there but declined the offer as director, and W. A. S. Hewins, a young economist at Pembroke College, Oxford, was appointed instead. With the support of the London County Council (LCC) the LSE flourished as a centre of learning.

On 27th February 1900, Edward Pease represented the Fabian Society at the meeting of socialist and trade union groups at the Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street, London. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour."

To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one member of the Fabian Society, and seven trade unionists. Some members of the Fabian Society had doubts about this and Edward Pease personally paid the affiliation dues.

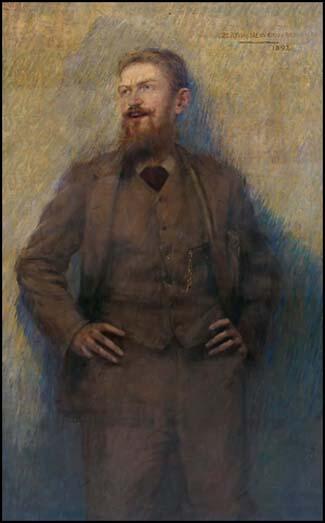

Bertha Newcombe, a Fabian member, painted the portrait of George Bernard Shaw. According to Margot Peters: "Shaw had begun to sit for his portrait to a Chelsea artist named Bertha Newcombe at her studio at Cheyne Walk on 14 February 1892. As the portrait progressed so did, inevitably, did the painters fascination with the sitter. On 17 February Shaw gave her a sitting until nine-thirty in the evening and dined with her afterward – she could not let him go home." The painting exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1893. An engraving of the painting was presented to the Fabian Society.

In 1912 Beatrice Webb established he Fabian Research Department. Its first secretary was Robin Page Arnot. He was later replaced by William Mellor. As Paul Thompson pointed out in his book, Socialist, Liberals and Labour (1967): "Its secretary was William Mellor and another leading member G. D. H. Cole, both young Oxford Fabians and both Guild Socialists. Together in April 1913 and March 1914 they led two attempts to disaffiliate the Fabian Society from the Labour Party. They failed, but when Cole resigned in 1915 he was able to take the Research Department with him, thus depriving the Fabian Society of its most talented younger members and resulting in its subsequent stagnation in the 1920s."

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Pease, History of the Fabian Society (1918)

At the second meeting of the Fabian Society on 25th January, 1884, reports were presented on a lecture by Henry George and a Conference of the Democratic Federation (later the Social Democratic Federation); the rules were adopted, and Mr. J. G. Stapleton read a paper on "Social conditions in England with a view to social reconstruction or development." This was the first of a long series of Fabian fortnightly lectures which have been continued ever since.

(2) Edith Nesbit, letter to Ada Breakell (February, 1884)

On Friday we went to Mr. Pease's to tea, and afterwards, a Fabian meeting was held. The meeting was over at 10 - but some of us stayed till 11.30 talking. The talks after the Fabian meeting are very jolly. I do think the Fabians are quite the nicest set of people I ever knew. Mr. Pease's people are Quakers and he has the cheerful serenity and self-containedness common to the sect. I like him very much.

(3) Edith Nesbit, letter to Ada Breakell (April, 1884)

I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes.

(4) Edward Pease, History of the Fabian Society (1918)

Fabian Essays, the work of seven writers (George Bernard Shaw, Annie Besant, Sydney Olivier, Sydney Webb, William Clarke, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas) all of them far above the average in ability, some of them possessing individuality now recognised as exceptional is a book and not a collection of essays. Bernard Shaw was the editor, and those who have worked with him know that he does not take lightly his editorial duties. He corrects his own writings elaborately and repeatedly, and he does as much for everything which comes into his care.

None of us at that time were sufficiently experienced in the business of authorship to appreciate the astonishing success of the venture. In a month the whole edition of 1,000 copies was exhausted. With the exception of Mrs. Besant, whose fame was still equivocal, not one of the authors had published any book of importance, held any public office, or was known to the public beyond the circles of London political agitators.

(5) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (21st September, 1894)

A few weeks ago Sidney (Webb) received a letter from a Derby solicitor informing him that he was left executor to a certain Mr Hutchinson. All he knew of the man (whom he had never seen) was the fact that he was an eccentric old gentleman, member of the Fabian Society, who alternately sent considerable cheques and wrote querulous letters about Shaw's rudeness, or some other fancied grievance he had suffered at the hands of some member of the Fabian Society. When Sidney heard he was made executor, he expected that the old man had left something to the Fabian Society. Now it turns out that he has left nearly £10,000 to five trustees and appointed Sidney chairman and administrator - all the money to be spent in ten years. The poor old man blew his brains out.

The question is how to spend the money. It might be placed to the credit of the Fabian Society and spent in the ordinary work of propaganda. Or a big political splash might be made with it - all the Fabian Executive might stand for Parliament. Sidney has been planning to persuade the other trustees to devote the greater part of the money to encouraging research and economic study. His vision is to to found, slowly and quietly, a 'London School of Economics and Political Science' - a centre not only of lectures on special subjects, but an association of students who would be directed and supported in doing original work.

(6) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (23rd January, 1895)

Last night we had an informal conference with the ILP leaders. Ramsay MacDonald and Frank Smith (who are members both of the Fabians and the ILP) have been for some time harping on the desirability of an understanding between the two societies. To satisfy them Sidney (Webb) arranged a little dinner of Keir Hardie, Tom Mann, Edward Pease and George Bernard Shaw and the two intermediaries. I think the principals on either side felt it would come to nothing. Nevertheless, it was interesting.

Tom Mann said the Progressives on the LCC were not convinced Socialists. No one should get the votes of the ILP who did not pledge himself to the 'Nationalisation of the Means of Production'. Keir Hardie, who impressed me very unfavourably, deliberately chooses this policy as the only one which he can boss. His only chance of leadership lies in the creation of an organisation "against the government"; he knows little and cares less for any constructive thought or action. But with Tom Mann it is different. he is possessed with the idea of a 'church' - of a body of men all professing exactly the same creed and all working in exact uniformity to exactly the same end. No idea which is not 'absolute', which admits of any compromise or qualification, no adhesion which is tempered with doubt, has the slightest attraction to him. And, as Shaw remarked, he is deteriorating. This stumping the country, talking abstractions and raving emotions, is not good for a man's judgment, and the perpetual excitement leads, among other things, to too much whisky.

I do not think the conference ended in any understanding. We made clear our position. We were a purely educational body, we did not seek to become a 'party'. We should continue our policy of inoculation, of giving to each class, to each person, that came under our influence the exact dose of collectivism that they were prepared to assimilate.

(7) The Fabians became very interested in the Hull House Settlement project in Chicago. Several members, including H. G. Wells, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb, visited the settlement. A resident of Hull House, Alice Hamilton, wrote about these visits in her autobiography, Exploring the Dangerous Trades (1943)

Our English visitors sometimes surprised us by combining social radicalism with a total lack of democratic feeling, which to our way of thinking was most inconsistent. A Fabian Socialist amused me very much when one morning I took him out into our neighborhood. He was talking eagerly about the need of vacation schools for London slum children as we stepped out into our courtyard, which was crowded with children waiting to go on a picnic in the country. He never saw them, at least not as slum children like those he was eager to help; he only saw them only as obstacles in his way, and he pushed them aside impatiently as if they were so many chickens, all the time telling me about the pitiful children in London. I thought to myself, "You may love humanity, but you certainly do not love your fellow man."

We found we could not always trust English radicals and Socialists to be nice to their American "comrades" when the latter were from an inferior social level, as most of them were, and we had some painful and embarrassing experiences when what was supposed to be a joyful meeting of kindred souls proved to be a meeting of the snubbers and the snubbed.

(8) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954)

My elder brother, Tom, was an architect and a great reader of Ruskin and Morris. I too admired these great men and began to understand their social gospel. My brother was helping at the Maurice Hostel in the nearby Hoxton district of London. Our reading became more extensive. After looking into many social reform ideas - such as co-partnership - we both came to the conclusion that the economic and ethical basis of society was wrong. We became socialists.

I recall how in October, 1907, we went to Clements Inn to try and join the Fabian Society. Edward Pease, the Secretary, regarded us as if we were two beetles who had crept under the door, and when we said we wanted to join the Society he asked coldly, "Why?" We said, humbly, that we were socialists and persuaded him we were genuine.

I remember very well the first Fabian Society meeting we attended at Essex Hall. The platform seemed to be full of bearded men: Aylmer Maude, William Sanders, Sidney Webb and Bernard Shaw. I said to my brother, "Have we got to grow a beard to join this show. H. G. Wells was on the platform, speaking with a little piping voice; he was very unimpressive.

(9) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

George Bernard Shaw agreed to take the chair for me at a Fabian Society meeting. The meeting was a great success. Shaw has always been a brilliant speaker as well as a provocative writer. During the early years of the Fabian Society he spoke constantly at public meetings, drawing crowded audiences. He always gave of his best, whether there were two thousand listeners or only twenty. That is the hallmark of the true artist.

(10) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

The Labour Party in those days suffered considerably from the anarchy of conflicting ideas, and it was not easy for me to fit in anywhere. From 1923 onwards I used to attend meetings and conferences organized by the Fabians and the I.L.P. The Fabians were serious people, rather with Civil Service minds, extremely rational and full of common sense. But they were too quiet to get the public ear. Their influence was with the 'high-ups' and a few of the people who mattered.

The I.L.P. had the mass appeal and the means to get their ideas across. But what a chaos, if the solid trade union people were not there to give it some stability! There were a large number of young women with short hair and young men with long. There were also the old pioneers who had been active in the movement before these young people were born. They thought that what Keir Hardie had said in the year one and the resolution passed by a conference in the 1890s was gospel and that it was sacrilege to alter it for something more practical in the 1920s. Socialism with these people was of the Utopian kind, a mixture of Robert Owen, William Morris and of the mid-Victorian social reformers. But they believed in democracy and thought that by propaganda a Parliamentary majority could be obtained for revolutionary changes.

(11) Paul Thompson, Socialist, Liberals and Labour (1967)

A leading part in the demand for an independent socialist party had been played by New Age, a paper taken over in 1907 by a Fabian schoolteacher from Leeds, A. B. Orage. He made it one of the liveliest papers of the period, notable regular contributors including Cecil Chesterton, J. A. Hobson, Patrick Geddes, Wyndham Lewis, St. John Ervine and Walter Sickert. New Age was in fact a rather brighter focus of intellectual socialism in this period than the Fabian Society itself. S. G. Hobson, who resigned from the Fabian Society in 1909 after failing to convert it to "the upbuilding of a definite and avowed Socialist Party", was a regular political contributor. Independent socialism, as we have seen, enjoyed only a short period of success, and New Age found a new hope in a modified version of the syndicalist movement, Guild Socialism, which was also to secure considerable support in the Fabian Society. It was a typically Fabian modification of syndicalism, preferring "encroaching control" to revolutionary strike action. Industrial unionism was rephrased in the form of industrial Guilds. These ideas were first put forward by New Age in an editorial series, written by Hobson, which began late in 1912.

The Guild Socialist rebellion was more difficult to quell, not only because it had the sympathy of Shaw, but also because the leading rebels had been entrenched in the Fabian organisation by the Webbs themselves. The research groups suggested by Beatrice Webb in 1912 developed into a Fabian Research Committee with its own office. Its secretary was William Mellor and another leading member G. D. H. Cole, both young Oxford Fabians and both Guild Socialists. Together in April 1913 and March 1914 they led two attempts to disaffiliate the Fabian Society from the Labour Party. They failed, but when Cole resigned in 1915 he was able to take the Research Department with him, thus depriving the Fabian Society of its most talented younger members and resulting in its subsequent stagnation in the 1920s.

The third political group within the Fabian Society, the supporters of clear commitment to the Labour Party, made two serious attempts to change Fabian policy. The first was in conjunction with Wells in 1906-7. Haden Guest, a fiery young Welsh doctor, had spoken in support of Wells' proposed reforms, arguing the need `to get at the middle classes and organise them to work in co-operation with the Labour Party'. Before the 1907 Fabian executive election a reform committee, including Wells, Guest and Ensor with Sydney Oliver in the chair, held meetings at the I.L.P. office. The committee failed because the conflict between Wells and the others was never settled.

(12) C. E. M. Joad, Under the Fifth Rib (1932)

I rather gather that they are swept by alternate waves of aestheticism and science - but in my time politics was the thing that mattered. Politics was in the air, and it was difficult to escape the contagion. The Fabian Society was in its hey-day, and most men at Oxford with any pretensions to be thought advanced were members of it. Complete with statistics we confounded Liberals and Tories in debate, read papers on State management, wrote articles on "workers' control", and introduced socialist theories into academic essays. The years 1910-14 were years of great industrial unrest; even in Oxford there were strikes, and at strikers' meetings we had our first taste of the joys of political oratory. I remember being fined for leading a procession of Oxford tram strikers to the Martyrs' Memorial where I addressed them in a revolutionary speech of blood, fire and thunder. Then, as always, public speaking went to my head. The spectacle of an audience helpless before you, the knowledge that for the time it is a passive receptacle to be filled with the content of your ideas, the feeling that you can make it thrill to the sound of your voice, vibrate in sympathy with your every mood, these things were, and to me they still are, the closest approximation to the sense of power that I have ever experienced. In my youth they intoxicated me. I spoke in season and out of season at College debating societies, took a pride in being the licensed buffoon of the Oxford Union, and practised the arts of orgiastic demagogy at meetings of discontented workers...