Hull House

In 1888, while on a tour of Europe, Jane Addams and Ellen Starr visited the university settlement of Toynbee Hall , in the East End of London. Named after the social reformer, Arnold Toynbee, the settlement was run by Samuel Augustus Barnett, canon of St. Jude's Church.

Situated in Commercial Street, Whitechapel, Toynbee Hall was Britain's first university settlement. The idea was to create a place where students from Oxford University and Cambridge University , during their vacations, could work among, and improve the lives of the poor. The settlement also served as a base for Charles Booth and his group of researchers working on the Life and Labour of the People in London .

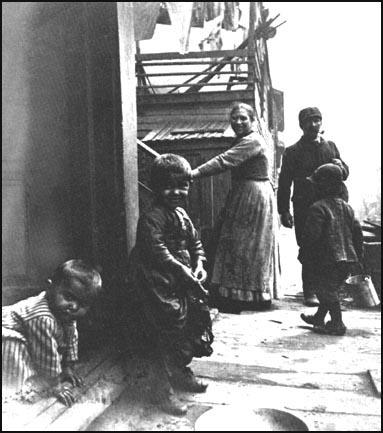

When Jane Addams and Ellen Starr returned to Chicago in 1889, they decided to start a similar project in Chicago. Helen Culver agreed to rent them Hull House for $60 a month. This large, abandoned mansion had been built by the wealthy businessman, Charles J. Hull, in 1856. Situated in Halstead Street in the run-down Nineteenth Ward of Chicago, most of the people living in the area were recently arrived immigrants from Europe including people from Germany, Italy, Sweden, England, Ireland, France, Russia, Norway, Austro-Hungary, Greece, Bulgaria, Holland, Portugal, Scotland, Wales, Spain and Finland.

Jane Addams and Ellen Starr moved in to Hull House on 18th September, 1889. They began by inviting people living in the area to hear readings from books and to look at slides of paintings. After talking to the visitors it soon became clear that the women had a desperate need for a place where they could bring their young children. Addams and Starr decided to start a kindergarten and provide a room where the mothers could sit and talk. Jenny Dow, who lived in an expensive part of Chicago, agreed to come to Hull House to run the nursery school. Within three weeks the kindergarten had enrolled twenty-four children with 70 more on the waiting list.

Other activities soon followed. Jane Addams ran a club for teenage boys and Ellen Starr provided lessons in cooking and sewing for local girls. University teachers, students and social reformers in Chicago were also recruited to provide free lectures on a wide variety of different topics. Over the years this included people such as John Dewey, Clarence Darrow, Susan B. Anthony, William Walling, Robert Hunter, Robert Lovett, Ernest Moore, Charles Beard, Paul Kellogg, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, Ray Stannard Baker, Francis Hackett, Henry Demarest Lloyd and Frank Lloyd Wright .

Inspired by the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin, the women decided to turn Hull House into an art gallery. While in Europe Jane Addams and Ellen Starr had collected reproductions of paintings and these were now hung in the various rooms of the house. Starr organized art classes and exhibitions as well as developing a scheme where people could borrow art reproductions to hang in their own homes.

Italian, German, Irish and French evenings were also organized. Local people presented songs, dances, games and food associated with their home country. This was probably the most successful of the settlement's early projects as it provided an opportunity for local people to make their own contribution to the venture. As Jane Addams later recalled, it soon became clear that the object of the settlement program should be to "help the foreign-born conserve and keep whatever of value their past life contained and to bring them into contact with a better class of Americans."

In 1890 Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr were joined at Hull House by Julia Lathrop. All three women had been students at Rockford Female Seminary together in the 1880s. Lathrop, who had been trained as a lawyer by her father, the United States senator, William Lathrop, was an excellent organizer, and took over the day to day running of the settlement.

Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr and Julia Lathrop gradually became more involved in the community where they were living. They were shocked by the poor housing, the overcrowding and the poverty that the people were having to endure. Addams wrote to her step-brother that she was "overpowered by the misery and narrow lives" of these people.

In the early days of Hull House, the three women were influenced by the Christian Socialism that had inspired the creation of Toynbee Hall. This was reinforced by the arrival in 1891 of Florence Kelley at Hull House. A member of the Socialist Labor Party, Kelley had considerable experience of political and trade union activity. It was Kelley who was mainly responsible for turning Hull House into a centre of social reform.

The presence of Florence Kelley in Hull House attracted other social reformers to the settlement. This included Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alice Hamilton, Charlotte Perkins, William Walling, Raymond Robins, Charles Beard, Mary McDowell, Mary Kenney, Alzina Stevens and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Working-class women, such as Kenney and Stevens, who had developed an interest in social reform as a result of their trade union work, played an important role in the education of the middle-class residents at Hull House. They in turn influenced the working-class women. As Kenney was later to say, they "gave my life new meaning and hope".

Florence Kelley and several other women based at Hull House carried out research into the sweating trade in Chicago and this led to the passing of the pioneering Illinois Factory Act (1893). Kelley was recruited by the state's new governor, John Peter Altgeld, as the chief factory inspector, and two other women involved in the research, Alzina Stevens and Mary Kenney, also became inspectors.

Helen Culver, who owned Hull House, also gave the women other adjacent property. Wealthy people in Chicago contributed money, including Louise Bowen who provided three quarters of a million dollars. This enabled the group to expand its activities. An art gallery was added in 1891, a coffee house and gymnasium in 1893, a club house in 1898 and a theatre in 1899.

In 1903 several women associated with Hull House, including Jane Addams, Mary Kenney, Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge, were involved in establishing the Women's Trade Union League. Union meetings were often held at Hull House and members of the settlement helped support workers during industrial disputes. This resulted in some wealthy people withdrawing their support from Hull House. One businessman wrote that Hill House had "been so thoroughly unionized that it has lost its usefulness and has become a detriment and harm to the community as a whole."

Many of the women at Hull House went on to play an important role in the reform movement and the development of social work as a profession. This included Florence Kelley (first woman chief factory inspector and head of the National Consumer's League); Julia Lathrop (head of the Children's Bureau, 1912-21); Mary Kenney (co-founder of Women's Trade Union League); Grace Abbott (director of the Immigrants' Protective League and head of Children's Bureau, 1921-34); Alice Hamilton (first woman professor at Harvard Medical School); Dorothy Detzer, Executive Secretary of Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, 1924-46); Edith Abbott (director of social research at the Chicago School of Civics and editor of Social Service Review ); Sophonisba Breckinridge (professor of social work at Chicago School of Civics), Mary McDowell (co-founder of Women's Trade Union League), Adena Miller Rich (vice-president of the League of Women Voters) and Jessie Binford (director of the Juvenile Protective Association).

Hull House was also visited by a large number of people who were to later have a profound impact on the development of the modern world. This included John Peter Altgeld, Mary White Ovington, Lillian Wald, Frances Perkins, George Herron, Raymond Robins, James Keir Hardie, John Morley, J. A. Hobson, H. G. Wells, John Burns, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Graham Wallas and William Stead .

The Hull House settlement received a considerable amount of publicity and soon spread to other cities in the United States. This included Andover House in Boston in 1891 and the Henry Street Settlement in New York, established by Lillian Wald in 1893. In 1897 there were 74 settlements in the United States and by 1900 there were over a hundred. In 1911 leaders of the social settlement movement, including Jane Addams of Hill House, founded the National Federation of Settlements .

The Hull House complex was not completed until 1907. The settlement now had thirteen buildings spread over a large city block. There were around 70 people living in Hull House and it cost the settlement over $26,500 to run the house and its programs. Rents and sales raised $12,000 but the rest had to come from donations.

Elizabeth Dilling claimed that Jane Addams was one of the most of the dangerous radicals in America: "Greatly beloved because of her kindly intentions toward the poor, Jane Addams has been able to do more probably than any other living woman to popularize pacifism and to introduce radicalism into colleges, settlements, and respectable circles. The influence of her radical proteges, who consider Hull House their home center, reaches out all over the world. One knowing of her consistent aid of the Red movement can only marvel at the smooth and charming way she at the same time disguises this aid."

After the death of of Jane Addams in 1935, Louise Bowen, president of the Hull House Association board of trustees, was the most important figure at Hull House. Bowen appointed Adena Miller Rich , director of the Immigrants' Protective League, as Hull House's head resident. Rich established a new Department of Naturalization and Citizenship. The main objective of this organization was to educate immigrants. Another innovation was the formation of the Housing and Sanitation Committee, that attempted to improve living conditions in Chicago .

Adena Miller Rich and Louise Bowen did not have a good relationship and disagreed about staff appointments, the use of funds, and the importance of the different Hull House programs. As Bowen controlled the funds, she normally made the final decisions and in April, 1937, Rich resigned.

Louise Bowen selected Charlotte Carr as the next head resident. Carr agreed with Adena Miller Rich that the most important objectve was help intergrate the various immigrant groups. At that time the Hull House community consisted of eighteen national groups: Italian, Greek, Mexican, British, Scandinavian, Polish, German, Russian, Czechoslovakian, French, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Swiss, Rumanian, Yugoslavian, Belgian, Finnish and Dutch.

Charlotte Carr established the Workers' Education Department and encouraged local people to join trade unions. Under Carr's leadership the Hull House Settlement grew rapidly and by 1940 it was estimated that 1,500 people entered the building every day. However, Carr's radical political views resulted in clashes with Louise Bowen. In 1943 Carr was fired when she refused to resign from the left-wing Union for Democratic Action.

Louise Bowen, whose health was now poor, decided to retire from active duty and instead became honorary president and treasurer. The trustees decided to appoint Russell Ballard as head resident. Ballard, a former school teacher, decided to place the focus on the welfare of children. By 1944 there were 685 children registered for daytime recreation activities and 275 for evening programs.

In 1959 the University of Illinois began looking for a site to build a new campus. The following year the city authorities suggested the area which housed the Hull House Settlement. The fight against this scheme was led by Jessie Binford and Florence Scala .

The struggle against closure was still going on when Russell Ballard decided to retire in February, 1962. Paul Jans became the new head resident but on 5th March, 1963, the trustees of Hull House accepted an offer of $875,000 for the settlement buildings. Jessie Binford and Florence Scala took the case to the Supreme Court but the ruling went against them and the Hull House Settlement was closed on 28th March, 1963. After complaints from long-time supporters of the settlement it was decided to preserve the original Hull House building and turn it into a museum.

Primary Sources

(1) Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House (1910)

I gradually became convinced that it would be a good thing to rent a house in a part of the city where many primitive and actual needs are found, in which young woman who had been given over too exclusively to study, might restore a balance of activity along traditional lines and learn of life from life itself.

With the advice of several of the oldest residents of Chicago we decided upon a location somewhere near the junction of Blue Island Avenue, Halstead Street and Harrison Street. I was surprised and overjoyed on the very first day of our search for quarters to come upon the hospitable old house built in 1856 for the homestead of one of Chicago's pioneer citizens, Mr. Charles J. Hull, and although battered by its vicissitudes, was essentially sound. It responded kindly to repairs, its wide hall and open fireplaces always insuring it a gracious aspect.

We furnished the house as we would furnished it were it in another part of the city, with the photographs and other impedimenta we had collected in Europe, and with a few bits of family mahogany. We believed that the settlement may logically bring to its aid all those adjuncts which the cultivated man regards as good and suggestive of the best life of the past.

(2) In 1960 Helen Hall, Director of the Henry Street Settlement in New York City, wrote about Jane Addams and Hull House.

Jane Addams founded Hull House in 1889. In settling on Halstead Street she deliberately put herself in a position to know intimately the people who were having the hardest time to survive in the city of Chicago. As Jane Addams experimented with immediate answers to her neighbour's needs she faced the necessity for the fundamental changes which took her far afield. She never dodged an issue no matter where it led her. Laws affecting immigrants, child labour, prostitution, labour's right to organize, the status of women, political reform at its roots, and social justice through the Progressive Party - and her passion for peace - all these and many more she saw as urgent demands upon her creative efforts and interpretative skills.

Aside from her own devotion and capacity, part of her success must have come from her ability to pick gifted people and to strengthen their hands as they worked. She recognized the capacities of those around her. No matter who they were, rich or poor, and drew them into her orbit of accomplishment. Hull House grew, as did her most far-reaching endeavors, as a result of her understanding of people and her ability to attract the most adventurous people of her day. That Jane Addams could work with people of equal strength and genius is proved by the names of her many associates who, with her, shared in turning philanthropy into social work. At the same time they were making possible much of the protective legislation of that day.

(3) Nora Marks, Chicago Tribune (19th May, 1890)

Miss Jane Addams and Miss Ellen Starr got tired of keeping their culture, and wealth, and social capacity to themselves. These young women believe that all luxury is right that can be shared. They have taken their books, pictures, learning, gentle manner, esthetic taste, to South Halsted Street.

From 9 to 12 a kindergarten under the direction of Miss Dow is held in the long drawing-room. In the afternoon the kindergarten furniture is removed and the hall is devoted to the use of various clubs and classes. With its beautiful walls and pictures it is easily turned into a drawing-room with the addition of a rug and chairs.

Monday afternoon the drawing-room is filled with Italian girls who sew, play games, and dance, and the little ones cut out pictures and paste them in scrapbooks. Sometimes they take a bath when they can be convinced of the beauty of the porcelain tubs.

Monday afternoon a club of young women meets and read Romola , aided by pictures of Florence, contemporary art, and lectures by Miss Starr on Florentine artists.

Monday evening belongs to the French, who are reviewing the old salons of Paris. Music, conversations, and coffee form the excuse for a brilliant evening, with an occasional lecture on Marie Antoinette and kindred subjects.

Tuesday afternoon the Schoolboys' Club meets, gets books from the circulating library, and has reading aloud. At the same time a girls' cooking class is at work in the kitchen. In the evening the boys come back and have a lecture on what to do in emergencies, or simple chemical experiments. One class is reading Shakespeare and others not so advanced are studying the three R's.

Wednesday evening the Workingmen's Discussion Club has the floor. The membership is already twenty-five, and many others who are interested attend. The Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones, Henry Demarest Lloyd, or some other well-known man delivers a short address, which is followed by the freest discussion on strikes, labour unions, the eight-hour question, child labour, etc.

Thursday afternoon Dr. Lelia Bedell talks to the women on physiology and hygiene and how to raise healthy children, even near the Chicago River. A cooking class is also being instructed. Thursday evening the German population turns out en masse for a social evening of reading, music, and "cakes and ale".

Friday afternoon the Schoolgirls' Club comes in to sew, embroider, and cook, each taking home a book from the library. Friday evening the working girls come in to enjoy a lecture or concert, and Saturday evening there is a typical Italian entertainment. These entertainments are crowded.

(4) Jane Addams, Philanthropy and Social Progress (1893)

The Settlement is an experimental effort to aid in the solution of the social and industrial problems which are engendered by the modern conditions of life in a great city. The one thing to be dreaded in the Settlement is that it lose its flexibility, its power of quick adaptation, its readiness to change its methods of its environment may demand. It must be open to conviction and must have a deep and abiding sense of tolerance.

It must be hospitable and ready for experiment. It should demand from its residents a scientific patience in the accumulation of facts and the steady holding of their sympathies as one of the best instruments for that accumulation. They must be content to live quietly side by side with their neighbours until they grow into a sense of relationship and mutual interested. Their neighbours are held apart by differences of race and language which the residents can more easily overcome. They are bound to see the needs of their neighbourhood as a whole, to furnish data for legislation, and use their influence to secure it. In short, residents are pledged to devote themselves to the duties of good citizenship and to the arousing of the social energies which too largely lie dormant in every neighbourhood given over to industrialism.

(5) Florence Kelley, Autobiography (1927)

On a snowy morning between Christmas 1891 and New Year's 1892, I arrived at Hull House, Chicago, a little before breakfast time, and found there Henry Standing Bear a Kickapoo Indian, waiting for the front door to be opened. It was Miss Addams who opened it, holding on her her left arm a singularly unattractive, fat, pudgy baby belonging to the cook.

At breakfast on that eventful morning, there were present Ellen Gates Starr, friend of many years and fellow-founder of Hull House with Jane Addams; Jennie Dow, a delightful young volunteer kindergartner, whose good sense and joyous good humor; Mary Keyser, who had followed Miss Addams from the family home in Cedarville and throughout the remainder of her life relieved Miss Addams of all household care.

(6) Mary Kenney wrote about her experiences at Hull House in her unpublished autobiography.

One day, while I was working at my trade, I received a letter from Miss Jane Addams. She invited me to for dinner. She said she wanted me to meet some people from England who were interested in the labour movement.

When I went into Hull House, I saw furnishings and large rooms different from anything I had ever seen before. With one look at the reception room, my first thought was, "If the Union could only meet here."

Miss Addams greeted me and introduced the guests from England and all the residents. My first impression was that they were all rich and not friends of the workers.

Small wages and the meagre way mother and I had been living had been making me grow more and more class conscious. By my manner Miss Addams must have known that I wasn't friendly. She asked me questions about our Trade Union. "Is there anything I can do to help your organization?" she said.

I couldn't believe I had heard right. "Does she really want to help our Trade Union?" I asked myself. She said, "I would like to help. What can I do?" I answered, "There are many things we need. We haven't a good meeting place. We are meeting over a saloon on Clark Street and it is a dirty and noisy place, but he can't afford anything better. I confided in her that, as I passed through the large reception room, I had thought of what a wonderful meeting place it would make.

"Can I help in any other way? she said. I said we needed someone to distribute circulars. She said she would. When I saw there was someone who cared enough to help us and to help us in our way, it was like having a new world opened up.

Miss Addams not only had the circulars distributed, but paid for them. She asked us how we wanted to have them worded. She climbed stairs, high and narrow. Many of the entrances were in back alleys. There were signs to "Keep Out". She managed to see the workers at their noon hour, and invited them to classes and meetings at Hull House.

Later, she asked me to come to Hull House to live. Knowing Hull House and what it stood for, I know it "heaven". My whole attitude toward life changed. I attended classes there. My first was in English. My first was in English. I realized for the first time how handicapped I was and how handicapped the children of other wage workers were that left school at fourteen.

(7) Alice Hamilton joined Hull House in 1898 and stayed for twenty-two years. Hamilton wrote about her experiences at Hull House in her autobiography, Exploring the Dangerous Trades (1943)

Life at Hull House was very simple so far as luxuries went, but it was full of beauty. Miss Addams and Miss Starr brought with them many charming furnishings, and whatever they bought had the two qualities of durability and beauty. Our food was inexpensive, but dinner was served to us in a long, paneled dinning room, lighted with chandeliers of Spanish wrought iron; breakfast in a charming little coffee-house built in imitation of an English inn. To me, the life there satisfied every longing, for companionship, for the excitement of new experiences, for constant intellectual stimulation, and for the sense of being caught up in a big movement which enlisted my enthusiastic loyalty.

My part in it was humble enough. At that time there were few of the social services which now we take as a matter of course. Hull House had to have its own day nursery, kindergarten, public baths, playground, as well as all the other activities which settlements still carry on. There were no baby clinics, and, though I did not feel at all competent to treat sick babies, I did venture to open a well-baby clinic which very soon was taking in all the older brothers and sisters, up to eight years of age.

Life in a settlement does several things to you. Among others, it teaches you that education and culture have little to do with real wisdom, the wisdom that comes from life experiences. If one's contact with the poor is only through their organizations, their clubs and trade unions, one gets a very one-sided, distorted impression of the working-class, which contains not only rebel youth but conservative middle age, not only the radical leader but his wife, who cares more for a nice flat and an electric refrigerator than for the emancipation of the workers.

(8) Edith Abbott, Social Service Review (September, 1950)

Hull House and the old West side were full of newly arrived immigrants when Grace and I went to live there in 1908; we seemed to be surrounded by great tenement areas which have now given way to the factories and stores that have come with the business invasion. Chicago at that time was the rushing, growing metropolis of the West, but the crowded streets about Hull House with their strange foreign signs and foreign-looking shops that were often very shabby and untidy seemed strangely unrelated to the great, prosperous city that was called the 'Queen of the West'.

The foreign colonies were well established, and there were Italians in front of us and to the right of us; and to the left a large Greek colony. There was a Bulgarian colony a few blocks west of Halsted Street and along to the north that had almost no women; but large numbers of fine Bulgarian men seemed to have emigrated - and they were pitiful when they were unemployed.

Then you came to the old Ghetto as you followed Hull House a few blocks to the south, where the Maxwell Street Market with its competing pushcarts heaped with shoes, stockings, potatoes, onions, old clothes, new clothes, dishes, pots and pans, and food for the Sunday trade was as picturesque as it was insanitary.

The Greeks were our nearest neighbours, and many of them came to Hull House for classes and clubs. The Greek immigrants at that time were mostly young men working for money to bring over their relatives. The Hull House residents and club leaders organized Greek clubs of various kinds and Greek dances, when there were so few Greek women that the women residents, young and old, were called in to "help the Greeks dance."

(9) Mary White Ovington, Reminiscences (1932)

There was a fervor for settlement work in the nineties, for learning working-class conditions by living among the workers and sharing, to a small extent, in their lives. Toynbee Hall, London, Hull House, Greenwich House, the Henry Street Settlement, these were a few familiar names.

I knew Jane Addams and have never forgotten her piece of advice to me: "If you want to be surrounded by second-rate ability, you will dominate your settlement. If you want the best ability, you must allow great liberty of action among your residents." Jane Addams's name today is among the most famous in the world. But perhaps few people realize the incalculable good she has done in helping others to enlarge and glorify their own work. Many people can build their fortune by using others. Few can encourage ability without dominating it.

(10) In her book, Twenty Years at Hull House (1910), Jane Addams described how an unemployed shipping clerk had arrived in 1893 at Hull House asking for help.

I told him of the opportunity for work on the drainage canal and intimated that if any employment were obtainable, he ought to exhaust that possibility before asking for help. The man replied that he had always worked indoors and that he could not endure outside work in winter. He did not come again for relief, but worked for two days digging on the canal, where he contracted pneumonia and died a week later. I have never lost trace of the two little children he left behind him, although I cannot see them without a bitter consciousness that it was at their expense I learned that life cannot be administered by definite rules and regulations; that wisdom to deal with a man's difficulties comes only through some knowledge of his life and habits as a whole; and that to treat an isolated episode is almost sure to invite blundering.

(11) John Dewey, The School as Social Centre (1902)

It is said that one ward in the city of Chicago has forty different languages represented in it. It is a well-known fact that some of the largest Irish, German, and Bohemian cities in the world are located in America, not in their own countries. The power of the public schools to assimilate different races to our own institutions, through the education given to the younger generation, is doubtless one of the most remarkable exhibitions of vitality that the world has ever seen.

But, after all, it leaves the older generation still untouched; and the assimilation of the younger can hardly be complete or certain as long as the homes of the parents remain comparatively unaffected. Indeed, wise observers in both New York and Chicago have recently sounded a note of alarm. They have called attention to the fact that in some respects the children are too rapidly, I will not say Americanized, but too rapidly de-nationalized. They lose the positive and conservative value of their own native traditions, their own native music, art, and literature. They do not get complete initiation into the customs of their new country, and so are frequently left floating and unstable between the two. They even learn to despise the dress, bearing, habits, language, and beliefs of their parents - many of which have more substance and worth than the superficial putting-on of the newly adopted habits.

One of the chief motives in the development of the new labour museum at Hull House has been to show the younger generation something of the skill and art and historic meaning in the industrial habits of the older generations - modes of spinning, weaving, metal working, etc., discarded in this country because there was no place for them in our industrial system. Many a child has awakened to an appreciation of admirable qualities hitherto unknown in his father or mother for whom he had begun to entertain a contempt. Many an association of local history and past national glory has been awakened to quicken and enrich the life of the family.

What we want is to see the school, every public school, doing something of the same sort of work that is now done by Hull House Settlement. It is a place where ideas and beliefs may be exchanged, not merely in the arena of formal discussion - for argument alone breeds misunderstanding and fixes prejudice - but in ways where ideas are incarnated in human form and clothed with the winning grace of personal life. Classes for study may be numerous, but all are regarded as modes of bringing people together, of doing away with barriers of caste, or class, or race, or type of experience that keep people from real communion with each other.

(12) Walter Lippmann, A Preface to Politics (1913)

Miss Addams has not only made Hull House a beautiful place; she has stocked it with curious and interesting objects. It is no accident that Hull House is the most successful settlement in America. Yet who does not feel its isolation in that brutal city. A little Athens in a vast barbarism - you wonder how much of Chicago Hull House can civilize. Hull House cannot remake Chicago. A few hundred lives can be changed, and for the rest it is a guide to the imagination. Like all utopias, it cannot succeed, but it may point the way to success. If Hull House is unable to civilize Chicago, it at least shows Chicago and America what a civilization might be like.

(13) Florence Scala was interviewed by Studs Terkel for his book Division Street: America (1967)

I grew up around Hull House, one of the oldest sections of the city. In those early days I wore blinders. I wasn't hurt by anything very much. When you become involved, you begin to feel the hurt, the anger. You begin to think of people like Jane Addams and Jessie Binford and you realize why they were able to live on. They understood how weak we really are and how we could strive for something better if we understood the way.

My father was a tailor, and we were just getting along in a very poor neighborhood. He never had any money to send us to school. When one of the teachers suggested that our mother send us to Hull House, life began to open up. At that time, the neighborhood was dominated by gangsters and hoodlums. They were men from the old country, who lorded it over the people in the area. It was the day of the moonshine. The influence of Hull House saved the neighborhood. It never really purified it. I don't think Hull House intended to do that.

For the first time my mother left the darn old shop to attend Mother's Club once a week. She was very shy, I remember. Hull House gave you a little insight into another world. There was something else to life beside sewing and pressing.

Sometimes as a kid I used to feel ashamed of where I came from because at Hull House I met young girls from another background. Even the kinds of food we ate sometimes you know, we didn't eat roast beef, we had macaroni. I always remember the neighborhood as a place that was alive. I wouldn't want to see it back again, but I'd like to retain the being together that we felt in those days.

(14) Francis Hackett worked as a journalist with the Chicago Evening Post when he became a resident at Hull House in 1906. He wrote about his experiences in an article that was published in The Survey (June, 1925)

When I went to live in Hull House in 1906, I did not really know it, and I was totally ignorant of settlement work as I was devoid of missionary spirit. I was torn at that time between the two impulses of wanting to know Chicago and wanting to escape from it, and I went to Hull House both for escape and for reconcilement.

I went there as one always goes into a new experience, on the terms and in the light of the inappropriate things I already knew. Only very slowly did I frame for myself the kind of experience I was having. As I trusted myself to it gradually and suspiciously, and felt it gave back more than it was receiving from me, I began to realize the peculiar quality of this strange American creation, its quality of goodness, of intelligence, of decent conscience, which filled Hull House almost to overflowing, and which renewed itself constantly from Miss Addams as a fountain is renewed. Hull House not only recruited strong characters, it was excited about them.

Hull House was American because it was international, and because it perceived that the nationalism of each immigrant was a treasure, a talent, which gave him a special value for the United States. We were flooded by nationalisms. How many nights did I not stay awake while the interminable whine of Greek folk-music came across Halsted Street to my exasperated ears? And if the Greeks were neighbours, with their sharp profiles and sharper wits, the Italians were not less neighbours. An Italian family lived in the House, the handsome matron who ran the coffee house, her seigniorial husband who was an editor, and the two boys, one chiselled Latin and the other a ball of Nordic-Latin energy. But there was also the stream of Italian life from the neighbourhood, the black eyes blazing out of immobile faces, the withered mothers, the gnarled fathers who seemed to carry with them the parched heat of a beating sun.

(15) Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, speech in Congress (1926)

It is of the utmost significance that practically all the radicalism started among women in the United States centers about Hull House, Chicago, and the Children's Bureau at Washington, with a dynasty of Hull House graduates in charge of it since its creation.

It has been shown that both the legislative program and the economic program - "social-welfare" legislation and "bread and peace" propaganda for internationalism of the food, farms, and raw materials of the world for their chief expression in persons, organizations, and bureaus connected with Hull House.

And Hull House has been able to cover its tracks quite effectively under the nationally advertised reputation of Miss Jane Addams as a social worker - who has often been painted by magazine and newspaper writers as a sort of modern Saint of the Slums - that both she and Hull House can campaign for the most radical movements, with hardly a breath of public suspicion.

(16) Elizabeth Dilling, The Red Network (1934)

Greatly beloved because of her kindly intentions toward the poor, Jane Addams has been able to do more probably than any other living woman to popularize pacifism and to introduce radicalism into colleges, settlements, and respectable circles. The influence of her radical proteges, who consider Hull House their home center, reaches out all over the world. One knowing of her consistent aid of the Red movement can only marvel at the smooth and charming way she at the same time disguises this aid.

(17) Congressional Record Report on Hull House (1926)

Florence Kelley has not only preached communism and urged a study of the fundamental communist books by college women taking up philanthropic or social work, but as president of the Intercollegiate Socialist League - the organization chiefly responsible for socialist propaganda in American schools and colleges - Miss Kelley has had great influence for a number of years in promoting radicalism among youth while in school.

It is of the utmost significance that practically all the radicalism started among women in the United States centers about Hull House, Chicago, and the Children's Bureau, at Washington, with a dynasty of Hull House graduates in charge of it since its creation.

Hull House itself has been able to cover its tracks quite effectively under the nationally advertised reputation of Miss Jane Addams as a social worker - who has often been painted by magazine and newspaper writers as a sort of modern Saint of the Slums - that both she and Hull House can campaign for the most radical measures and lead the most radical movement, with hardly a breadth of public suspicion.

(18) Milton Mayer, Atlantic Monthly (December, 1938)

A few months ago a "fat Irishwoman" (as she described herself) decided she'd seen enough front-line service for a while. For twenty years she had manned the barricades, as a policewoman under Brooklyn Bridge, as Secretary of Labor of war-torn Pennsylvania, and as director of relief in New York City. Now she was tired and forty-seven (though she looked neither) and she wanted a furlough. What she got was one of the toughest assignments in America.

Charlotte Carr is probably the only graduate of boarding school and Vassar who ever walked a beat. Tonight she dominates a drawing-room with native grace; tomorrow she dominates a relief demonstration with native persuasion. Her long service on behalf of the hard-bitten under-privileged has awakened in this well-born women the traits of her ancestors. They, seven or eight generations back, were meat-and-potatoes Irish.

When Jane Addams moved into Hull House, forty-eight years ago, Chicago's nineteenth ward was one of the plague spots of America - an unrelieved slum, rotting and stinking within and eating its way into the rest of the careless city. In the square mile between Hull House and the river there was one bathtub. There were no parks or playgrounds. For every pickpocket clubbed by the police there were twenty maturing in every poolroom. The children of the immigrants earned four cents an hour at piecework on garments.

Hull House had two jobs, from the first. One was to make the poor less miserable in their poverty. The other was to make them less poor. The first had the blessings of Chicago's "leading citizens"; the second did not. Jane Addams and Hull House fought the city. They forced Chicago to establish a juvenile court, to build small parks and playgrounds where the children of the poor could get at them. They forced Illinois to pass factory inspection laws, the eight-hour day for women, and a workmen's compensation act. By their example, they carried these reforms to many another city and state.

When Charlotte Carr took over, the place was a museum, a shrine to Jane Addams. The thousands who still poured through its doors came to see not what Hull House was doing but what it it had done. The bloody battleground had become a "must" item for out-of-town tourists. Tinted memories overlay the scenes of Jane Addams' struggles. The crusaders were gone. Hull House had become Chicago's toy

(19) Chicago Daily News (January, 1943)

Charlotte Carr and the trustees of Hull House have parted company. The trustees of Hull House pay the bills. Therefore it is their show. Charlotte Carr is a hired hand, and if she wants to take part in politics, she should do it on her own time. And if the people who use the facilities of Hull House insist on participating in its management, they are forgetting their place. So I image, runs the reasoning of the trustees. And if I were a trustee, I would probably feel that way myself. When you give a dog a bone it's no fun having him snap at you.

(20) Charlotte Carr gave an interview to Time Magazine after she was forced to resign by Louise Bowen (11th January, 1943)

"Hell, I was fired!" exclaimed Charlotte Carr last week at reports that she had "resigned" after five years as director of Chicago's world-famed slum settlement, Hull House. For many reasons, Charlotte Carr's position at Hull House had become shaky. Some trustees and philanthropists in particular did not like her outspoken political activity, her affiliation with the Union for Democratic Action.

Hull House's founder, Jane Addams, in the 19th Century spirit believed in the social adjustment and education of the alien poor. Miss Carr thought that times had changed, that organization and political pressure were now the best ways for slum dwellers to better their lot.

Tall, heavy and gusty, Charlotte Carr calls herself "a fat Irishwoman" and is a female counterpart of John L. Lewis - more a labor leader than a social worker.

(21) A Hull House resident who supported Charlotte Carr against the trustees was interviewed by the Chicago Daily News after she was dismissed in January, 1943.

The fundamental point is: who shall formulate the policies of Hull House? Does Hull House belong to the people it serves, or to the trustees? Shall it be an 'agency' superimposed from above; or shall it be an instrument of the people themselves? Only by involving the people significantly in the management of Hull House can it ever become a real part of the attitudes, sentiments and thinking of the people.

Formerly the largest proportion of our adult population was foreign born. But our community has now come of age. Most of the adults are native-born, were educated in American schools and act and think as Americans. We believe that our people are capable of participating in the management of our educational and social welfare institutions.

Because Charlotte Carr was thoroughly familiar with conditions as they are, and was in complete accord with our aspirations for democracy, we consider her resignation an irreparable loss to our community. And we hope that the trustees will reconsider it.

(22) In 1967 Florence Scala told Studs Terkel about how she campaigned with Jessie Binford to save the Hull House Settlement (1967)

In the early sixties, the city realized it had to have a campus, a Chicago branch of the University of Illinois. There were several excellent areas to choose from, where people were not living: a railroad site, an industrial island near the river, an airport used by businessmen, a park, a golf course. The mayor looked for advice. One of his advisers suggested our neighborhood as the ideal site for the campus. We were dispensable. When the announcement came in 1961, it was a bombshell. What shocked us was the amount of land they decided to take. They were out to demolish the whole community.

A member of the Hull House Board took me to lunch a couple of times at the University Club. My husband said, go, go, have a free lunch and see what it is she wants. What she wanted me to do, really, was to dissuade me from protesting. There was no hope, no chance, she said.

I shall never forget one board meeting. It hurt Miss Binford more than all the others. That afternoon, we came with a committee, five of us, and with a plea. We remended them of the past, what we meant to each other. From the moment we entered the room to the time we left, not one board member said a word to us.

Miss Binford was in her late eighties. Small, birdlike in appearance. She sat there listening to our plea and then she reminded them of what Hull House meant. She talked about principles that must never waver. No one answered her. Or acknowledged her. Or in any way showed any recognition of what she was talking about. It's as though we were talking to a stone wall, a mountain. The shock of not being able to have any conversation with the board members never really left her. She felt completely rejected. Something was crushed inside her. The Chicago she knew had died.