Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the highest federal court in the United States. Its existence is provided for in Article III of the Constitution, although Congress is given the power to determine the size of the Court. The size of the court is set by Congress and currently consists of a Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices.

Members of the Supreme Court are appointed for life by the President. They may be removed only by death, resignation or impeachment. The Supreme Court has the power of judicial review. It may declare acts of Congress or of state governments unconstitutional and therefore invalid. The Supreme Court decides cases by a majority vote and its decisions are final.

Franklin D. Roosevelt came into conflict with the Supreme Court during his period in office. The chief justice, Charles Hughes, had been the Republican Party presidential candidate in 1916. Herbert Hoover appointed Hughes in 1930 and had led the court's opposition to some of the proposed New Deal legislation. This included the ruling against the National Recovery Administration (NRA), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) and ten other New Deal laws.

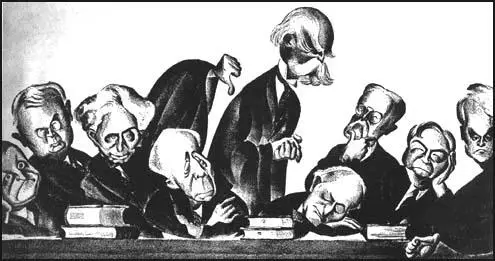

On 2nd February, 1937, Franklin D. Roosevelt made a speech attacking the Supreme Court for its actions over New Deal legislation. He pointed out that seven of the nine judges (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, George Sutherland, Harlan Stone, Owen Roberts, Benjamin Cardozo and Pierce Butler) had been appointed by Republican presidents. Roosevelt had just won re-election by 10,000,000 votes and resented the fact that the justices could veto legislation that clearly had the support of the vast majority of the public.

Roosevelt suggested that the age was a major problem as six of the judges were over 70 (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, James McReynolds, Louis Brandeis, George Sutherland and Pierce Butler). Roosevelt announced that he was going to ask Congress to pass a bill enabling the president to expand the Supreme Court by adding one new judge, up to a maximum off six, for every current judge over the age of 70.

Charles Hughes realised that Roosevelt's Court Reorganization Bill would result in the Supreme Court coming under the control of the Democratic Party. His first move was to arrange for a letter written by him to be published by Burton Wheeler, chairman of the Judiciary Committee. In the letter Hughes cogently refuted all the claims made by Roosevelt.

However, behind the scenes Hughes was busy doing deals to make sure that Roosevelt's bill would be defeated in Congress. On 29th March, Owen Roberts announced that he had changed his mind about voting against minimum wage legislation. Hughes also reversed his opinion on the Social Security Act and the National Labour Relations Act (NLRA) and by a 5-4 vote they were now declared to be constitutional.

Then Willis Van Devanter, probably the most conservative of the justices, announced his intention to resign. He was replaced by Hugo Black, a member of the Democratic Party and a strong supporter of the New Deal. In July, 1937, Congress defeated the Court Reorganization Bill by 70-20. However, Roosevelt had the satisfaction of knowing he had a Supreme Court that was now less likely to block his legislation.

Justices of the Supreme Court have included John Harlan (1877-1911), David Brewer (1890-1910), Henry Billings Brown (1891-1906), Oliver Wendell Holmes (1902-1932), Charles Hughes (1910-1941), Willis Van Devanter (1911-1937), James McReynolds (1914-1941), Louis Brandeis (1916-1939), Howard Taft (1921-30), George Sutherland (1922-1938), Pierce Butler (1923-1939), Harlan Stone (1925-1941), Owen Roberts (1930-1945), Benjamin Cardozo (1932-1938), Hugo Black (1937-71), Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962), William Douglas (1939-1975), Frank Murphy (1940-1949) and Thurgood Marshall (1967-1991).

Primary Sources

(1) Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio broadcast, Fireside Chat (9th March, 1937)

Tonight, sitting at my desk in the White House, I make my first radio report to the people in my second term of office.

I am reminded of that evening in March, four years ago, when I made my first radio report to you. We were then in the midst of the great banking crisis.

Soon after, with the authority of the Congress, we asked the Nation to turn over all of its privately held gold, dollar for dollar, to the Government of the United States.

Today's recovery proves how right that policy was.

But when, almost two years later, it came before the Supreme Court its constitutionality was upheld only by a five-to-four vote. The change of one vote would have thrown all the affairs of this great Nation back into hopeless chaos. In effect, four Justices ruled that the right under a private contract to exact a pound of flesh was more sacred than the main objectives of the Constitution to establish an enduring Nation.

In 1933 you and I knew that we must never let our economic system get completely out of joint again - that we could not afford to take the risk of another great depression.

We also became convinced that the only way to avoid a repetition of those dark days was to have a government with power to prevent and to cure the abuses and the inequalities which had thrown that system out of joint.

We then began a program of remedying those abuses and inequalities - to give balance and stability to our economic system - to make it bomb-proof against the causes of 1929.

Today we are only part-way through that program - and recovery is speeding up to a point where the dangers of 1929 are again becoming possible, not this week or month perhaps, but within a year or two.

National laws are needed to complete that program. Individual or local or state effort alone cannot protect us in 1937 any better than ten years ago.

It will take time - and plenty of time - to work out our remedies administratively even after legislation is passed. To complete our program of protection in time, therefore, we cannot delay one moment in making certain that our National Government has power to carry through.

Four years ago action did not come until the eleventh hour. It was almost too late.

If we learned anything from the depression we will not allow ourselves to run around in new circles of futile discussion and debate, always postponing the day of decision.

The American people have learned from the depression. For in the last three national elections an overwhelming majority of them voted a mandate that the Congress and the President begin the task of providing that protection - not after long years of debate, but now.

The Courts, however, have cast doubts on the ability of the elected Congress to protect us against catastrophe by meeting squarely our modern social and economic conditions.

We are at a crisis in our ability to proceed with that protection. It is a quiet crisis. There are no lines of depositors outside closed banks. But to the far-sighted it is far-reaching in its possibilities of injury to America.

I want to talk with you very simply about the need for present action in this crisis - the need to meet the unanswered challenge of one-third of a Nation ill-nourished, ill-clad, ill-housed.

Last Thursday I described the American form of Government as a three horse team provided by the Constitution to the American people so that their field might be plowed. The three horses are, of course, the three branches of government - the Congress, the Executive and the Courts. Two of the horses are pulling in unison today; the third is not. Those who have intimated that the President of the United States is trying to drive that team, overlook the simple fact that the President, as Chief Executive, is himself one of the three horses.

It is the American people themselves who are in the driver's seat.

It is the American people themselves who want the furrow plowed.

It is the American people themselves who expect the third horse to pull in unison with the other two.

I hope that you have re-read the Constitution of the United States in these past few weeks. Like the Bible, it ought to be read again and again.

It is an easy document to understand when you remember that it was called into being because the Articles of Confederation under which the original thirteen States tried to operate after the Revolution showed the need of a National Government with power enough to handle national problems. In its Preamble, the Constitution states that it was intended to form a more perfect Union and promote the general welfare; and the powers given to the Congress to carry out those purposes can be best described by saying that they were all the powers needed to meet each and every problem which then had a national character and which could not be met by merely local action.

But the framers went further. Having in mind that in succeeding generations many other problems then undreamed of would become national problems, they gave to the Congress the ample broad powers "to levy taxes ... and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States."

That, my friends, is what I honestly believe to have been the clear and underlying purpose of the patriots who wrote a Federal Constitution to create a National Government with national power, intended as they said, "to form a more perfect union ... for ourselves and our posterity."

For nearly twenty years there was no conflict between the Congress and the Court. Then Congress passed a statute which, in 1803, the Court said violated an express provision of the Constitution. The Court claimed the power to declare it unconstitutional and did so declare it. But a little later the Court itself admitted that it was an extraordinary power to exercise and through Mr. Justice Washington laid down this limitation upon it: "It is but a decent respect due to the wisdom, the integrity and the patriotism of the legislative body, by which any law is passed, to presume in favor of its validity until its violation of the Constitution is proved beyond all reasonable doubt."

But since the rise of the modern movement for social and economic progress through legislation, the Court has more and more often and more and more boldly asserted a power to veto laws passed by the Congress and State Legislatures in complete disregard of this original limitation.

In the last four years the sound rule of giving statutes the benefit of all reasonable doubt has been cast aside. The Court has been acting not as a judicial body, but as a policy-making body.

When the Congress has sought to stabilize national agriculture, to improve the conditions of labor, to safeguard business against unfair competition, to protect our national resources, and in many other ways, to serve our clearly national needs, the majority of the Court has been assuming the power to pass on the wisdom of these acts of the Congress - and to approve or disapprove the public policy written into these laws.

That is not only my accusation. It is the accusation of most distinguished justices of the present Supreme Court. I have not the time to quote to you all the language used by dissenting justices in many of these cases. But in the case holding the Railroad Retirement Act unconstitutional, for instance, Chief Justice Hughes said in a dissenting opinion that the majority opinion was "a departure from sound principles," and placed "an unwarranted limitation upon the commerce clause." And three other justices agreed with him.

In the case of holding the AAA unconstitutional, Justice Stone said of the majority opinion that it was a "tortured construction of the Constitution." And two other justices agreed with him.

In the case holding the New York minimum wage law unconstitutional, Justice Stone said that the majority were actually reading into the Constitution their own "personal economic predilections," and that if the legislative power is not left free to choose the methods of solving the problems of poverty, subsistence, and health of large numbers in the community, then "government is to be rendered impotent." And two other justices agreed with him.

In the face of these dissenting opinions, there is no basis for the claim made by some members of the Court that something in the Constitution has compelled them regretfully to thwart the will of the people.

In the face of such dissenting opinions, it is perfectly clear that, as Chief Justice Hughes has said, "We are under a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the judges say it is."

The Court in addition to the proper use of its judicial functions has improperly set itself up as a third house of the Congress - a super-legislature, as one of the justices has called it - reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there, and which were never intended to be there.

We have, therefore, reached the point as a nation where we must take action to save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself. We must find a way to take an appeal from the Supreme Court to the Constitution itself. We want a Supreme Court which will do justice under the Constitution and not over it. In our courts we want a government of laws and not of men.

I want - as all Americans want - an independent judiciary as proposed by the framers of the Constitution. That means a Supreme Court that will enforce the Constitution as written, that will refuse to amend the Constitution by the arbitrary exercise of judicial power - in other words by judicial say-so. It does not mean a judiciary so independent that it can deny the existence of facts which are universally recognized.

How then could we proceed to perform the mandate given us? It was said in last year's Democratic platform, "If these problems cannot be effectively solved within the Constitution, we shall seek such clarifying amendment as will assure the power to enact those laws, adequately to regulate commerce, protect public health and safety, and safeguard economic security." In other words, we said we would seek an amendment only if every other possible means by legislation were to fail.

When I commenced to review the situation with the problem squarely before me, I came by a process of elimination to the conclusion that, short of amendments, the only method which was clearly constitutional, and would at the same time carry out other much needed reforms, was to infuse new blood into all our Courts. We must have men worthy and equipped to carry out impartial justice. But, at the same time, we must have Judges who will bring to the Courts a present-day sense of the Constitution - Judges who will retain in the Courts the judicial functions of a court, and reject the legislative powers which the courts have today assumed.

(2) Emanuel Celler, wrote about President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Supreme Court in his autobiography, You Never Leave Brooklyn (1953)

Congress, with their individual traits, attitudes, and even passions, broke loose in 1937.

The first, the longest, and the loudest clamor against Roosevelt came with his plan for the reorganization of the Supreme Court. It shocked the Congress. I wonder now why the shock was so great. There was a consistency in Roosevelt's logic which we chose utterly to ignore. The "nine old men" on the bench were products of another age, tempered by social attitudes which the people had rejected in the bitterness of the depression. They had not swum in the swift rivers of the

times and could not comprehend the currents. The Supreme Court could, by judicial interpretation, undo the work of the Congress and the President. Constitutional interpretation is just as much a matter of temperament as it is the knowledge of precedents. Yesterday's minority opinion becomes the majority opinion of today.

But we were shocked. I believe that we were looking for absolutes. The delicate constitutional balances must not be disturbed. In the rapid succession of legislative enactments, many of which were based on untried political theory, the Supreme Court, not subject to the short-ranging pressures of each day, was the brake against the impetuous, the experimental. In the Supreme Court lay certainty, assurance, and authority. These must not be disturbed.

(3) Emanuel Celler, speech in Congress (13th April, 1937)

It is not the Constitution, but a debatable construction of the Constitution adopted by a bare majority of the Court, which has been blocking the New Deal program. I deplore the cunning manner in which some opponents of the President have been carrying on a Nationwide campaign to obscure this fact; and to make the people believe that Congress and the President have been trying to exercise powers which were clearly unconstitutional. I say this despite the fact that I disagree with the President's plan for six young additional Judges to replace those eligible for retirement. I sympathize with the President's objective but disagree with his method of obtaining it.

For four years all the reactionary forces in the United States have been trying to convince the people that adequate laws could not be enacted by the Congress to aid the farmers, the wage earners, and small-business men, because the Constitution prohibited all such laws. But the fact is that the Constitution grants ample power to the Congress to pass such needed legislation, according to the opinions of several Justices of the Supreme Court, and of many other judges and lawyers of high authority and reputation. In other words, I believe the majority of the Supreme Court was wrong and the minority right.

When one group of lawyers and judges upholds the constitutionality of desirable laws and another group declares such laws to be unconstitutional it is perfectly plain that, in the language of Chief Justice Hughes, 'the Constitution is what the judges say it is.'

The Constitution has not prevented New Deal legislation. It is the judges who interpret the Constitution to conform to their ideas of public policy, and who do not believe in the wisdom of the New Deal program, who have blocked that

program. They have nullified legislation which other judges equally able and learned hold to be within the powers of Congress. But, I repeat, the President has, I believe, taken the wrong means to prevent future nullification of New Deal legislation. Asking for six new appointments, if six over seventy fail to resign, is a rather bitter pill for the nation to swallow.