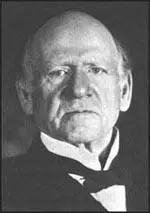

John Harlan

John Harlan was born in Boyle County, Kentucky, on 1st June, 1833. He worked as a lawyer and county judge before joining the Union Army during the American Civil War. Harlan commanded an infantry regiment but was critical of Abraham Lincoln and objected to the Emancipation Proclamation.

After the war Harlan attacked the Thirteenth Amendment which abolished slavery. However, after the emergence of racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan he changed his mind and became a supporter of the Radical Republicans and the Reconstruction Acts.

In 1877 President Rutherhood Hayes appointed Harlan as a member of the Supreme Court. Over the next few years Harlan showed he was a strong supporter of African-American civil rights. In 1883 he dissented from the majority view that Congress could not punish discrimination against African Americans by private persons. As a member of the Supreme Court Harlan was a consistent supporter of the Thirteenth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment. and warned that African Americans were in danger of being consigned to a "permanent condition of legal inferiority." In 1896 he was the only member of the Supreme Court who believed that segregation in railway cars was unconstitutional.

In 1897 New York Legislature passed a law that set the hours of bakers at no more than ten hours a day or sixty a week. In 1905 the owner of a bakery was fined $50 for violating the law. He appealed to the Supreme Court and it voted 5-4 that the law was unconstitutional. Harlan and Oliver Wendell Holmes were two of those four justices who disagreed with the decision that was to hold back the passing of social welfare legislation.

John Harlan died in Washington on 14th October, 1911.

Primary Sources

(1) John Harlan, dissenting opinion on the case of Homer Plessy, an African-American who in 1896 appealed to the Supreme Court after being convicted by a Louisiana court for riding in a white only railway car.

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is colour-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.

In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his colour when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. It is therefore to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land, has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race.

Sixty millions of whites are in no danger from the presence here of 8 million blacks. The destinies of the two races in this country are indissolubly linked together, and the interests of both require that the common government of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under the sanction of law. What can more certainly arouse race hate, what will more certainly create and perpetuate a feeling of distrust between these races than state enactments, which, in fact, proceed on the ground that coloured citizens are so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens?

(2) In 1897 New York Legislature passed a law that set the hours of bakers at no more than ten hours a day or sixty a week. In 1905 the owner of a bakery was fined $50 for violating the law. He appealed to the Supreme Court and it voted 5-4 that the law was unconstitutional. John Harlan was one of those four justices who disagreed with this vote.

It is plain that this statute was enacted in order to protect the physical well-being of those who work in bakery and confectionery establishments. It may be that the statute had its origin, in part, in the belief that employers and employees in such establishments were not upon an equal footing, and that the necessities of the latter often compelled them to submit to such exactions as unduly taxed their strength. Be this as it may, the statute must be taken as expressing the belief of the people of New York that, as a general rule, and in the case of the average man, labour in excess of sixty hours during a week in such establishments may endanger the health of those who thus labour.

I submit that this Court will transcend its functions if it assumes to annul the statute of New York. It must be remembered that this statute does not apply to all kinds of business. It applies only to work in bakery and confectionery establishments, in which, as all know, the air constantly breathed by workmen is not as pure and helpful as that to be found in some other establishments or out-of-doors. Professor Hirt in his treatise on the Diseases of the Workers has said: "The labour of the bakers is among the hardest and most laborious imaginable, because it has to be performed under conditions injurious to the health of those engaged in it."

(3) John Harlan explained why he had supported restrictions on the activities of the Standard Oil Company in 1890 (May, 1911).

All who recall the condition of the country in 1890 will remember that there was everywhere, among the people generally, a deep feeling of unrest. The nation had been rid of human slavery, but the conviction was universal that the country was in real danger from another kind of slavery sought to be fastened on the American people, namely, the slavery that would result from aggregations of capital in the hands of a few individuals and corporations controlling, for their own profit and advantage exclusively, the entire business of the country, including the production and sale of the necessaries of life. Such a danger was thought to be then imminent, and all felt that it must be met firmly and by such statutory regulations as would adequately protect the people against oppression and wrong.