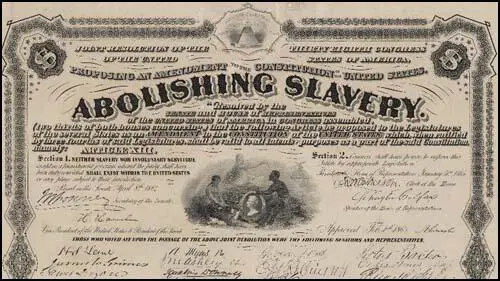

13th Amendment

On 23rd September, 1862 Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation. The statement said that all slaves would be declared free in those states still in rebellion against the United States on 1st January, 1863. The measure only applied to those states which, after that date, came under the military control of the Union Army. It did not apply to those slave states such as Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri and parts of Virginia and Louisiana, that were already occupied by Northern troops.

It was not until December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution had been passed by the House of Representatives and had been ratified by the required number of states, that slavery was finally abolished everywhere in the United States.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) John Greenleaf Whittier, letter to William Lloyd Garrison (24th November, 1863)

For, while we may well thank God and congratulate one another on the prospect of the speedy emancipation of the slaves of the United States, we must not for a moment forget that from this hour new and mighty responsibilities devolve upon us to aid, direct, and educate these millions left free, indeed, but bewildered, ignorant, naked, and foodless in the wild chaos of civil war.

We have to undo the accumulated wrongs of two centuries, to remake the manhood which slavery has well-nigh unmade, to see to it that the long-oppressed colored man has a fair field for development and improvement, and to tread under our feet the last vestige of that hateful prejudice which has been the strongest external support of Southern slavery. We must lift ourselves at once to the true Christian attitude where all distinctions of black and white are overlooked in the heartfelt recognition of the brotherhood of man.

I love, perhaps too well, the praise and good-will of my fellow-men; but I set a higher value on my name as appended to the Antislavery Declaration of 1833 than on the title-page of any book. Looking over a life marked by many errors and shortcomings, I rejoice that I have been able to maintain the pledge of that signature, and that, in the long intervening years, "My voice, though not the loudest has been heard. Wherever Freedom raised her cry of pain."

Let me, through thee, extend a warm greeting to the friends, whether of our own or the new generation, who may assemble on the occasion of commemoration. There is work yet to be done which will task the best efforts of us all. For thyself, I need not say that the love and esteem of early boyhood have lost nothing by the test of time.

(2) William Lloyd Garrison, speech at Charleston, South Carolina (14th April, 1865)

In 1829 I first hoisted in the city of Baltimore the flag of immediate, unconditional, uncompensated emancipation; and they threw me into their prison for preaching such gospel truth. My reward is, that in 1865 Maryland has adopted Garrisonian Abolitionism, and accepted a constitution indorsing every principle and idea that I have advocated in behalf of the oppressed slave.

The first time I saw that noble man, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, at Washington, - and of one thing I feel sure, either he has become a Garrisonian Abolitionist, or I a Lincoln Emancipationist, for I know that we blend together, like kindred drops, into one, and his brave heart beats freedom everywhere, - I then said to him: "Mr. President, it is thirty-four years since I visited Baltimore; and when I went their recently to see if I could find the old Prison, and, get into my old cell again, I found that all was gone." The President answered promptly and wittily, as he is wont to make his responses: "Well, Mr. Garrison, the difference between 1830 and 1864 appears to be this, that in 1830 you could not get out, and in 1864 you could not get in." This symbolizes the revolution which has been brought about in Maryland. For if I had spoken till I was as hoarse as I am tonight against slaveholders in Baltimore, there would have been no indictment brought against me, and no prison opened to receive me.

But a broader, sublimer basis than that, the United States has at last rendered its verdict. The people, on the eighth of November last, recorded their purpose that slavery in our country should be forever abolished; and the Congress of the United States at its last session adopted, and nearly the requisite states have already voted in favor of, an amendment to the Constitution of the country, making it forever unlawful for any many to hold property in man. I thank God in view of these great changes.

Abolitionism, what is it? Liberty. What is liberty? Abolitionism. What are they both? Politically, one is the Declaration of Independence; religiously, the other is the Golden Rule of our Savior. I am here in Charleston, South Carolina. She is smitten to the dust. She has been brought down from her pride of place. The chalice was put to her lips, and she has drunk it to the dregs. I have never been her enemy, nor the enemy of the South, and in the desire to save her from this great retribution demanded in the name of the living God that every fetter should be broken, and the oppressed set free.

I have not come here with reference to any flag but that of freedom. If your Union does not symbolize universal emancipation, it brings no Union for me. If your Constitution does not guarantee freedom for all, it is not a Constitution I can ascribe to. If your flag is stained by the blood of a brother held in bondage, I repudiate it in the name of God. I came here to witness the unfurling of a flag under which every human being is to be recognized as entitled to his freedom. Therefore, with a clear conscience, without any compromise of principles, I accepted the invitation of the Government of the United States to be present and witness the ceremonies that have taken place today.

And now let me give the sentiment which has been, and ever will be, the governing passion of my soul: "Liberty for each, for all, and forever!"