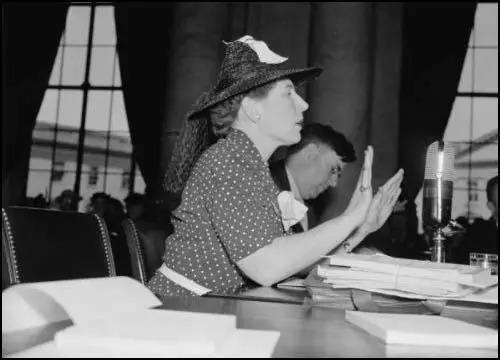

Dorothy Detzer

Dorothy Detzer was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, on 1st December, 1893. Her father, August Detzer, was a drugstore owner and her mother, Laura Goshorn Detzer, was a librarian. She later described her childhood in her autobiography: "In my early teens there was a brief period when I decided to be a toe dancer and, as a dying swan, to swoon in a heap of tulle and tossed bouquets just as Pavlova did. As I was a fairly good dancer this dream was not wrought merely out of romantic fantasy, but it was a dream which received little encouragement from my wide-awake family. I was reminded that I was no beauty, and that the success of a professional dancer lay along a road paved with grueling work and perpetual heartbreak. So the dream died like the swan, leaving no tangible residue except a correct posture and overmuscular ankles. During this period, I certainly never thought about the issues of war and peace. I learned from snatches of grownup conversation that the Spaniards were dreadful people who had once blown up an American ship, and that the droopily mustached Dewey whose picture dominated the center of some blue World's Fair plates was a great American hero. Then there was also the bedtime story of Jackanapes. From it I gathered that war was a sad but beautiful adventure. Its closing paragraphs led one through a series of rhetorical questions to noble heights."

In her late teens Detzer spent time travelling in the Far East before settling in Chicago, where she went to live in Hull House where she met Jane Addams, Ellen Starr, Julia Lathrop, Florence Kelley, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alice Hamilton, Charlotte Perkins, William Walling, Charles Beard, Mary McDowell, Mary Kenney, Alzina Stevens and Sophonisba Breckinridge. Working-class women, such as Kenney and Stevens, who had developed an interest in social reform as a result of their trade union work, played an important role in the education of the middle-class residents at Hull House. They in turn influenced the working-class women. As Kenney was later to say, they "gave my life new meaning and hope". Detzer also studied at the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy while working as an officer of the Juvenile Protective Association.

During the First World War her twin brother, Donald Detzer, served in the United States Army. In 1918, while serving in a Field Hospital, he was a victim of a mustard gas attack. His lungs were badly damaged and he eventually died from a related illness. As a result of this, Dorothy became a pacifist. She later recalled: "Yet the movement for peace which developed during the crucial years which spanned two wars was never a private crusade; it was a co-operative, shared adventure. A movement rises out of the expanded aspirations of a few, and those who are identified with it soon recognize that painful but paradoxical truth: how unimportant to a movement is any individual - and how important."

After working for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) in Europe she returned to the United States and became national secretary of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). Her primary job was to lobby senators and representatives in Washington D.C. In Appointment on the Hill (1948) she argued: "I became a lobbyist. No doubt, to many Americans, such an avowal can only appear as a bold and shameless confession. For I know that to the general public, lobbying is a vocation tainted with many unsavory connotations. Perhaps this is natural since virtue is rarely news, and hence it is the disreputable lobbyists who invariably make the headlines. But there are good lobbyists as well as bad, and the good ones, I believe, have contributed in no small measure to the vitality and integrity of American political democracy. For American political democracy is no myth; it is a manifest reality. Out of my own long experience as a lobbyist in Washington, that fact, I believe, stands out in my mind more sharply than any other. Moreover, it is a fact which never ceased to surprise me. For the United States covers an enormous geographic area; it functions under a complicated, and sometimes clumsy, government machinery; it is infested by alert, moneyed interests; it is always contaminated by the unethical and unscrupulous breed of lobbyists."

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso: "Legislators respected Detzer for her thorough research, persuasive manner, and great integrity, knowing full well that the fashionable, outspoken Lady Lobbyist (as she was known) would accept no personal favours, private dinners or backroom deals that would compromise her work." Detzer lobbied Congress for legislation to allow alien conscientous objectors to become U.S. citizens, to end lynching, for the removal of U.S. troops in Haiti and Nicaragua and for the 1928 Kellog-Briand Pact. Along with Mabel Vernon she co-ordinated the petition campaign that collected more than half a million U.S. signatures in support of universal disarmament.

In 1933 Dorothy Detzer approached Gerald P. Nye, George Norris and Robert La Follette and asked them to instigate a Senate investigation into the international munitions industry. They agreed and on 8th February, 1934, Nye submitted a Senate Resolution calling for an investigation of the munitions industry by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under Key Pittman of Nevada. Pittman disliked the idea and the resolution was referred to the Military Affairs Committee. It was eventually combined with one introduced earlier by Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan, who sought to take the profits out of war.

Public hearings before the Munitions Investigating Committee began on 4th September, 1934. In the reports published by the committee it was claimed that there was a strong link between the American government's decision to enter the First World War and the lobbying of the the munitions industry. The committee was also highly critical of the nation's bankers. In a speech in 1936 Gerald P. Nye argued that "the record of facts makes it altogether fair to say that these bankers were in the heart and center of a system that made our going to war inevitable".

Hede Massing met Dorothy Detzer at the home of Noel Field in 1935: "A friendship with her started that was to last. She was, at the time, the secretary of the Woman's International League for Peace and Freedom in Washington... Here was a person I liked, who taught me more than anyone else about the workings of democracy in the United States.... I am proud to say that we are intimate friends today, and that our friendship has only deepened through the years."

Detzer left the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in 1946. She now spent her time looking after her ageing parents and writing her memoirs, Appointment on the Hill (1948). A close friend of Norman Thomas, she was also active in his Post War World Council, a group that was committed to developing plans for peace that would prevent all future wars.

In 1954 Detzer married the journalist and long-term friend, Ludwell Denny. They spent the next few years working for the Scripps-Howard organization. After her husband's death in 1970 she moved to Monterey, California, where she died on 7th January, 1981.

Primary Sources

(1) Dorothy Detzer, Appointment on the Hill (1948)

In my early teens there was a brief period when I decided to be a toe dancer and, as a dying swan, to swoon in a heap of tulle and tossed bouquets just as Pavlova did. As I was a fairly good dancer this dream was not wrought merely out of romantic fantasy, but it was a dream which received little encouragement from my wide-awake family. I was reminded that I was no beauty, and that the success of a professional dancer lay along a road paved with grueling work and perpetual heartbreak. So the dream died like the swan, leaving no tangible residue except a correct posture and overmuscular ankles.

During this period, I certainly never thought about the issues of war and peace. I learned from snatches of grownup conversation that the Spaniards were dreadful people who had once blown up an American ship, and that the droopily mustached Dewey whose picture dominated the center of some blue World's Fair plates was a great American hero. Then there was also the bedtime story of Jackanapes. From it I gathered that war was a sad but beautiful adventure. Its closing paragraphs led one through a series of rhetorical questions to noble heights.

(2) Dorothy Detzer, Appointment on the Hill (1948)

"The only good histories," said Montaigne, "are those written by the persons themselves who commanded in the affairs whereof they write." But if there is validity in this contention, there is also a flaw. No one individual ever commands alone in the affairs whereof he writes, nor do mutual experiences bring the same impacts, the same emotional response to those who share them. For no two chroniclers can see events with the same eyes; feel the compulsions of those events with the same heart; nor measure their significance with the same mind. Therefore, Montaigne's good histories will reflect not only the dogmas and bias, the aspirations and values of the participant who reports them, but they will inevitably spotlight him in the most conspicuous place upstage.

This book is no exception. It is a personal record, and like all personal records, it is heavily encrusted with "the most disgusting pronoun."

Yet the movement for peace which developed during the crucial years which spanned two wars was never a private crusade; it was a co-operative, shared adventure. A movement rises out of the expanded aspirations of a few, and those who are identified with it soon recognize that painful but paradoxical truth: how unimportant to a movement is any individual-- and how important. He is unimportant since the Cause alone is paramount; he is important only because every deflection, every hesitant loyalty weakens that Cause. And if the Cause exists only for the promotion of a principle, and offers none of the seductions of power, it will attract a leadership which is both disinterested and dedicated.

(3) Dorothy Detzer, Appointment on the Hill (1948)

From the morning in 1925, when I first went to see William Borah, the Capitol became a central focus of my work, and I became a lobbyist. No doubt, to many Americans, such an avowal can only appear as a bold and shameless confession. For I know that to the general public, lobbying is a vocation tainted with many unsavory connotations. Perhaps this is natural since virtue is rarely news, and hence it is the disreputable lobbyists who invariably make the headlines.

But there are good lobbyists as well as bad, and the good ones, I believe, have contributed in no small measure to the vitality and integrity of American political democracy. For American political democracy is no myth; it is a manifest reality. Out of my own long experience as a lobbyist in Washington, that fact, I believe, stands out in my mind more sharply than any other. Moreover, it is a fact which never ceased to surprise me. For the United States covers an enormous geographic area; it functions under a complicated, and sometimes clumsy, government machinery; it is infested by alert, moneyed interests; it is always contaminated by the unethical and unscrupulous breed of lobbyists.

(4) Dorothy Detzer, in her autobiography Appointment on the Hill (1948) reported a conversation she had with George Norris in 1933 about Gerald P. Nye leading the investigation into the international munitions industry.

Nye's young, he has inexhaustible energy, and he has courage. Those are all important assets. He may be rash in his judgments at times, but it's the rashness of enthusiasm. I think he would do a first-class job with an investigation. Besides, Nye doesn't come up for election again for another four years; by that time the investigation would be over. If it reveals what I am certain it will, such an investigation would help him politically, not harm him. And that would not be the case with many senators. For you see, there isn't a major industry in North Dakota closely allied to the munitions business.

(5) Dorothy Detzer, Appointment on the Hill (1948)

There was a brief period, before the Nazi party became an active menace to the world, when life seemed to open up a new pathway to peace. Germany had a republican government; Russia was busy with her "new experiment" - and Geneva was busy with hers. So between 1928 and 1934, the activities of the peace movement forged ahead steadily both in Europe and America. The ridicule and suspicion, which had beset most peace efforts during the decade following the First World War, were gradually being dissipated, and a season of fruitful promise seemed to open just ahead. Not that the officers and members of the peace organizations saw a warless world as any easy or imminent possibility. They held none of the wistful illusions expressed by a young newspaperwoman who, on interviewing Jane Addams, inquired what her next activities would be "now that peace was just around the corner." For those who worked in the field of peace knew too well the complexities and tensions of contemporary international life; and they minimized none of the difficulties. But by the nineteen-thirties, the peace movement had come of age; it was alive, vigorous, self-conscious.