Robert La Follette

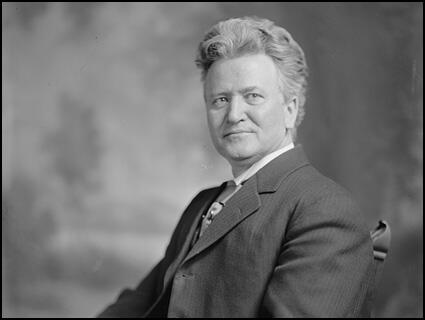

Robert La Follette, the son of a small farmer, was born in Dane County, Wisconsin, on 14th June, 1855. He worked as a farm labourer before entering the University of Wisconsin in 1875.

In 1876 La Follette met Robert G. Ingersoll. He later recalled: "Ingersoll had a tremendous influence upon me, as indeed he had upon many young men at the time. It was not that he changed my beliefs, but he liberated my mind. Freedom was what preached: he wanted the shackles off everywhere. He wanted men to think boldly about all things: he demanded intellectual and moral courage." After graduating in 1879 he set up as a lawyer and the following year became District Attorney of Dane County.

Elected to Congress as a Republican, La Follette was extremely critical of the behaviour of some of the party bosses. In 1891, La Follette announced that the state Republican boss, Senator Philetus Sawyer, had offered him a bribe to fix a court case.

Over the next six years La Follette built up a loyal following within the Republican Party in opposition to the power of the official leadership. Proposing a programme of tax reform, corporation regulation and an extension of political democracy, La Follette was elected governor of Wisconsin in 1900.

Once in power La Follette employed the academic staff of the University of Wisconsin to draft bills and administer the laws that he introduced. He later recalled: "I made it a policy, in order to bring all the reserves of knowledge and inspiration of the university more to the service of the people, to appoint experts from the university wherever possible upon the important boards of the state - the civil service commission, the railroad commission and so on - a relationship which the university has always encouraged and by which the state has greatly profited."

La Follette was also successful in persuading the federal government to introduce much needed reforms. This included the regulation of the railway industry and equalized tax assessment. In 1906 La Follette was elected to the Senate and over the next few years argued that his main role was to "protect the people" from the "selfish interests". He claimed that the nation's economy was dominated by fewer than 100 industrialists. He went on to argue that these men then used this power to control the political process. La Follette supported the growth of trade unions as he saw them as a check on the power of large corporations.

In 1909 La Follette and his wife, the feminist, Belle La Follette founded the La Follette's Weekly Magazine. The journal campaigned for women's suffrage, racial equality and other progressive causes. Lincoln Steffens argued: "La Follette is the opposite of a demagogue. Capable of fierce invective, his oratory is impersonal; passionate and emotional himself, his speeches are temperate. Some of them are so loaded with facts and such closely knit arguments that they demand careful reading, and their effect is traced to his delivery, which is forceful, emphatic, and fascinating."

La Follette supported Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential election and approved his social justice legislation. However, he complained that he was under the control of big business and was totally opposed to Wilson's decision to enter the First World War. Once war was declared La Follette opposed conscription and the passing of the Espionage Act. La Follette was accused of treason but was a popular hero with the anti-war movement.

Lincoln Steffens was a great supporter of La Follette: "Governor La Follette was a powerful man, who, short but solid, swift and willful in motion, in speech, in decision, gave the impression of a tall, a big man... what I saw at my first sight of him was a sincere, ardent man who, whether standing, sitting, or in motion, but the grace of trained strength, both physical and mental... Rather short in stature, but broad and strong, he had the gift of muscled, nervous power, he kept himself in training all his life. His sincerity, his integrity, his complete devotion to his ideal, were indubitable; no one who heard could suspect his singleness of purpose or his courage."

La Follette became the candidate of the Progressive Party in the 1924 presidential election. Although he gained support from trade unions, individuals like Fiorello La Guardia and Vito Marcantonio, the Socialist Party and the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, La Follette and his running partner, Burton K. Wheeler, only won one-sixth of the votes.

Robert La Follette died on 18th June, 1925.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert La Follette, Autobiography (1911)

In 1876 Robert G. Ingersoll came to Madison to speak. Ingersoll had a tremendous influence upon me, as indeed he had upon many young men at the time. It was not that he changed my beliefs, but he liberated my mind. Freedom was what preached: he wanted the shackles off everywhere. He wanted men to think boldly about all things: he demanded intellectual and moral courage. He wanted men to follow whatever truth might lead them. He was a rare, bold, heroic figure.

(2) Robert La Follette, Autobiography (1911)

William McKinley drew men to him by the charm, courtliness, and kindliness of his manner. McKinley was a magnetic speaker; he had a clear, bell-like quality of voice, with a thrill in it. He spoke with dignity, but with freedom of action. The pupils of his eyes would dilate until they were almost black, and the face, naturally without much colour, would become almost like marble - a strong face with a noble head.

I know of my own knowledge that McKinley stood against many of the corrupt influences within his own party - that he even stood firmly against the demands of his best friend, Hanna.

(3) When Robert La Follette became governor of Wisconsin in 1900 he began to appoint people from the local university.

I made it a policy, in order to bring all the reserves of knowledge and inspiration of the university more to the service of the people, to appoint experts from the university wherever possible upon the important boards of the state - the civil service commission, the railroad commission and so on - a relationship which the university has always encouraged and by which the state has greatly profited.

(4) Lincoln Steffens, The Struggle for Self-Government (1906)

"They" say in Wisconsin that La Follette is a demagogue, and if it is, demagogy to go thus straight to the voters, then "they" are right. But then Folk also is a demagogue, and so are all thoroughgoing reformers. La Follette from the beginning has asked, not the bosses, but the people for what he wanted, and after 1894 he simply broadened his field and redoubled his efforts. He circularized the State, he made speeches every chance he got, and it the test of demagogy is the tone and style of a man's speeches, La Follette is the opposite of a demagogue. Capable of fierce invective, his oratory is impersonal; passionate and emotional himself, his speeches are temperate. Some of them are so loaded with facts and such closely knit arguments that they demand careful reading, and their effect is traced to his delivery, which is forceful, emphatic, and fascinating.

(5) Robert La Follette, Autobiography (1911)

Benjamin Harrison was a man of superior ability. Reserved, undemonstrative, a bit austere in manner, direct, quick to grasp a proposition and decide on its merits, Harrison was a strong executive, commanding the respect and confidence of all whom he came in contact. He was conservative but not what we would call today a reactionary.

(6) Robert La Follette, Autobiography (1911)

In 1905 I recommended a graduated income tax which has since been adopted by the state. It is the most comprehensive income tax system yet adopted in this country. The tax as 1 per cent begins on incomes above $800 in the case of unmarried people and above $1,200 in the case of married persons, increasing one half of 1 per cent of thereabout for each additional $1,000, until $12,000 is reached, when the tax becomes 5.5 per cent. On incomes above $12,000 a year the tax is 6 per cent.

Wisconsin today leads all the states of the union in the proportion of its taxes collected from corporations. It derives 70 per cent of its total state taxes from the source, while the next nearest state, Ohio, derives 52 per cent.

All of these new sources of income have enabled us to increase greatly the service of the state to the people without noticeably increasing the burden upon the people. Especially have we built up our educational system.

(7) Robert La Follette, speech on railroad companies (23rd April, 1906)

The public has reasoned out its case. For more than a generation of time it has wrought upon this great question with heart and brain in its daily contact with the great railway corporations. It has mastered all the facts. It is just. It is honest. It is rational. It respects property rights. It well knows that its own industrial and commercial prosperity would suffer and decline if the railroads were wronged, their capital impaired, their profits unjustly diminished.

For a generation the American people have watched the growth of this power in legislation. They observe how vast and far-reaching these modem business methods are in fact. Against the natural laws of trade and commerce is set the arbitrary will of a few masters of special privilege. The principal transportation lines of the country are so operated as to eliminate competition. Between railroads and other monopolies controlling great natural resources and most of the necessaries of life there exists a "community of interests" in all cases and an identity of ownership in many. They have observed that these great combinations are closely associated in business for business reasons; that they are also closely associated in politics for business reasons; that together they constitute a complete system; that they encroach upon the public rights, defeat legislation for the public good, and secure laws to promote private interests.

Is it to be marveled at that the American people have become convinced that railroads and industrial trusts stand between them and their representatives; that they have come to believe that the daily conviction of public officials for betrayal of public trust in municipal. State, and national government is but a suggestion of the potential influence of these great combinations of wealth and power?

(8) Robert La Follette, speech (4th April, 1917)

If we are to enter upon this war in the manner the President demands, let us throw pretense to the winds, let us be honest, let us admit that this is a ruthless war against not only Germany's Army and her Navy but against her civilian population as well, and frankly state that the purpose of Germany's hereditary European enemies has become our purpose.

Again, the President says "we are about to accept the gage of battle with this natural foe of liberty and shall, if necessary, spend the whole force of the nation to check and nullify its pretensions and its power." That much, at least, is clear; that program is definite. The whole force and power of this nation, if necessary, is to be used to bring victory to the Entente Allies, and to us as their ally in this war. Remember, that not yet has the "whole force" of one of the warring nations been used.

Countless millions are suffering from want and privation; countless other millions are dead and rotting on foreign battlefields; countless other millions are crippled and maimed, blinded, and dismembered; upon all and upon their children's children for generations to come has been laid a burden of debt which must be worked out in poverty and suffering, but the "whole force" of no one of the warring nations has yet been expended; but our "whole force" shall be expended, so says the President. We are pledged by the President, so far as he can pledge us, to make this fair, free, and happy land of ours the same shambles and bottomless pit of horror that we see in Europe today.

Just a word of comment more upon one of the points in the President's address. He says that this is a war "for the things which we have always carried nearest to our hearts - for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own government." In many places throughout the address is this exalted sentiment given expression.

It is a sentiment peculiarly calculated to appeal to American hearts and, when accompanied by acts consistent with it, is certain to receive our support; but in this same connection, and strangely enough, the President says that we have become convinced that the German government as it now exists - "Prussian autocracy" he calls it - can never again maintain friendly relations with us. His expression is that "Prussian autocracy was not and could never be our friend," and repeatedly throughout the address the suggestion is made that if the German people would overturn their government, it would probably be the way to peace. So true is this that the dispatches from London all hailed the message of the President as sounding the death knell of Germany's government.

But the President proposes alliance with Great Britain, which, however liberty-loving its people, is a hereditary monarchy, with a hereditary ruler, with a hereditary House of Lords, with a hereditary landed system, with a limited and restricted suffrage for one class and a multiplied suffrage power for another, and with grinding industrial conditions for all the wageworkers. The President has not suggested that we make our support of Great Britain conditional to her granting home rule to Ireland, or Egypt, or India. We rejoice in the establishment of a democracy in Russia, but it will hardly be contended that if Russia was still an autocratic government, we would not be asked to enter this alliance with her just the same.

(9) Robert La Follette, Autobiography (1911)

While Theodore Roosevelt was President, his public utterances through state papers, addresses, and the press were highly coloured with rhetorical radicalism. One trait was always pronounced. His most savage assault upon special interests was invariably offset with an equally drastic attack upon those who were seeking to reform abuses. These were indiscriminately classed as demagogues and dangerous persons. In this way he sought to win approval, both from the radicals and the conservatives.

(10) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

I finished up in Chicago, then called on Governor LaFollette at Madison. I saw him before he saw me, and what I saw was a powerful man who, short but solid, swift and willful in motion, in speech, in decision, gave the impression of a tall, a big, man. He had meant to be an actor; he was one always. His lines were his own, but he consciously, artfully recited them well and for effect which, like an artist, he calculated. But what I saw at my first sight of him was a sincere, ardent man who, whether standing, sitting, or in motion, had the grace of trained strength, both physical and mental. When my name was whispered to him he came at me, running. LaFollette received me eagerly as a friend, as a partisan of his, a life-saver. He had read my articles on other cities and States and assumed, of course, that I would be on his side. I did not like this. I was coming over, but it takes time to change your mind, and I was not yet over on his side. He was not aware of my troubles, had not heard of my secret visit to Milwaukee; and he was in trouble himself. He was at a crisis in his career. Elected governor and in power, he had failed to do all that he had promised. The old machinery, by bribery, blackmail, threats, and women, had taken away from LaFollette enough of "his" legislators to defeat or amend his bills, and they were getting ready to beat him at the polls by accusing him of radicalism for proposing such measures, and of inefficiency and fraud for failing to pass them. He had no sufficient newspaper support. He feared that he could not explain it all to his own people, and he felt that the hostile opinion of the country outside his State, which the old Wisconsin machine was representing, was hurting him at home. He needed a friend; he needed just what I could give him, national, non-partisan support. He took me home for supper with his family, who all greeted me warmly, even intimately, on the assumption that I was their ally. I stood it for a while, then I repelled Mrs. LaFollette with a rebuke that was rude and ridiculous, so offensive indeed that I find that I cannot confess it even now. Fola LaFollette, who was there, said afterward that she never has felt so sorry for any two people as for her mother and me. My excuse was, and it is, that I had a vague plan to work up my article on LaFollette out of nothing but what his enemies were giving me; any friendly intimacy between me and the LaFollettes might spoil the effect I wished to get. And I did draw my clinching facts from the old machine men. I saw more of the opposition in Wisconsin than I did in any other similar situation. But shame for my gross discourtesy and my sense of the anxious search the governor was making of the horizon for rescue made me compromise. I closed in on him with a proposition that he take the time to tell me his whole story from boyhood on, both the good and the bad of it, his mistakes and his crimes as well as his intentions, ideals, and high purposes, leaving it to me to write it as I pleased. He agreed; he thought it over for a few days and decided, "Yes. I'll do it - at the St. Louis Exposition, where I have to visit the Wisconsin exhibition and building. I have to be there anyway. I'll have only formal duties to perform. Most of the time I am there I can spend with you. I'll tell you everything, everything, and leave it to you to deal with as you see fit."

Bob La Follette was called a little giant. Rather short in stature, but broad and strong, he had the gift of muscled, nervous power, he kept himself in training all his life. His sincerity, his integrity, his complete devotion to his ideal, were indubitable; no one who heard could suspect his singleness of purpose or his courage. The strange contradictions in him were that he was a fighter - for peace; he battered his fist so terribly in one great speech for peace during the World War that he had to be treated and then carried it in bandages for weeks.

(11) The Daily Worker (10th April, 1924)

We are against La Follette. We know that the political victory of the workers and exploited farmers lies over the dead body (politically) of La Follette. We will say this to the working class of this country. If, in spite of what we say, the masses of workers and exploited farmers who are not yet Communists, insist upon nominating La Follette and placing their hope upon him, we will not desert them in the struggle. We will go along with them and vote for their candidate, but at every stage of development we will point out that their hopes are illusions.