Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Steffens, the son of a wealthy businessman, Joseph Steffens, was born in San Francisco, California, on 6th April, 1866. The family moved to Sacramento. "It was off the line of the city's growth, but it was near a new grammar school for me and my sisters, who were coming along fast after me."

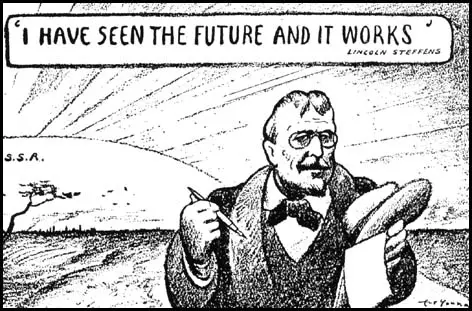

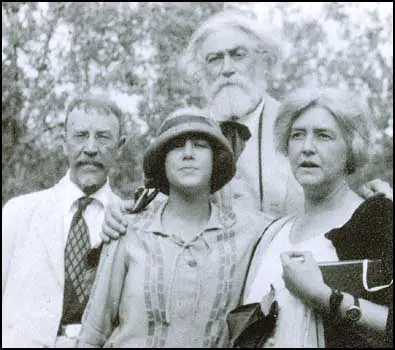

At the University of California he developed radical political views. "It is possible to get an education at a university. It has been done; not often, but the fact that a proportion, however small, of college students do get a start in interested, methodical study, proves my thesis... My method might lose a boy his degree, but a degree is not worth so much as the capacity and the drive to learn... My method was hit on by accident and some instinct. I specialized. With several courses prescribed, I concentrated on the one or two that interested me most, and letting the others go, I worked intensively on my favorites. In my first two years, for example, I worked at English and political economy and read philosophy. At the beginning of my junior year I had several cinches in history. Now I liked history; I had neglected it partly because I rebelled at the way it was taught, as positive knowledge unrelated to politics, art, life, or anything else.... The bare record of the story of man, with names, dates, and irrelative events, bored me. But I had discovered in my readings of literature, philosophy, and political economy that history had light to throw upon unhistorical questions. So I proposed in my junior and senior years to specialize in history." In 1889 Lincoln Steffens travelled to Berlin. He also stayed in Heidelberg, Leipzig, Paris and London before moving to New York City. In 1892 Steffens became a reporter on the New York Evening Post. In 1902 McClure's Magazine began to specialize in what became known as muckraking journalism. On the advice of Norman Hapgood, the owner, Samuel McClure recruited Steffens as editor of the magazine. In his autobiography, Steffens described McClure as: "Blond, smiling, enthusiastic, unreliable, he was the receiver of the ideas of his day. He was a flower that did not sit and wait for the bees to come and take his honey and leave their seeds. He flew forth to find and rob the bees." Writers who worked for the magazine during this period included Jack London, Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair, Willa Cather, Ray Stannard Baker and Burton J. Hendrick. In 1902 Lincoln Steffens wrote about St. Louis: "Go to St. Louis and you will find the habit of civic pride in them; they still boast. The visitor is told of the wealth of the residents, of the financial strength of the banks, and of the growing importance of the industries; yet he sees poorly paved, refuse-burdened streets, and dusty or mud-covered alleys; he passes a ramshackle firetrap crowded with the sick and learns that it is the City Hospital: he enters the Four Courts, and his nostrils are greeted with the odor of formaldehyde used as a disinfectant and insect powder used to destroy vermin; he calls at the new City Hall and finds half the entrance boarded with pine planks to cover up the unfinished interior. Finally, he turns a tap in the hotel to see liquid mud flow into wash basin or bathtub." Steffens later said that during this period he was so popular that "I couldn't travel in a train without seeing someone reading one of my articles." Lincoln Steffens recruited Ida Tarbell as a staff writer. Tarbell's 20-part series on Abraham Lincoln doubled the magazine's circulation. In 1900 this material was published in a two-volume book, The Life of Abraham Lincoln. Steffens was interested in using McClure's Magazine to campaign against corruption in politics and business. This style of investigative journalism that became known as muckraking. Tarbell's articles on John D. Rockefeller and how he had achieved a monopoly in refining, transporting and marketing oil appeared in the magazine between November, 1902 and October, 1904. This material was eventually published as a book, History of the Standard Oil Company (1904). Rockefeller responded to these attacks by describing Tarbell as "Miss Tarbarrel". The New York Times commented that" Miss Tarbell's fine analytical powers and gift for popular interpretation stood her in good stead" in the articles that she wrote for the magazine. A collection of Lincoln Steffens's articles appeared in the book The Shame of the Cities (1904). This was followed by an investigation into state politicians, The Struggle for Self-Government (1906). He praised some politicians such as Robert La Follette: "La Follette from the beginning has asked, not the bosses, but the people for what he wanted, and after 1894 he simply broadened his field and redoubled his efforts. He circularized the State, he made speeches every chance he got, and it the test of demagogy is the tone and style of a man's speeches, La Follette is the opposite of a demagogue. Capable of fierce invective, his oratory is impersonal; passionate and emotional himself, his speeches are temperate. Some of them are so loaded with facts and such closely knit arguments that they demand careful reading, and their effect is traced to his delivery, which is forceful, emphatic, and fascinating." Steffens also approved of Seth Low: "The mayor of New York, Seth Low, was a business man and the son of a business man, rich, educated, honest, and trained to his political job. Seth Low and his party in power and his backers were not radicals in any sense. Mr. Low himself was hardly a liberal; he was what would be called in England a conservative. He accepted the system; he took over the government as generations of corrupters had made it, and he was trying, without any fundamental change, and made it an efficient, orderly business-like organization for the protection and the furtherance of all business, private and public." As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "Lincoln Steffens was attracted to younger men and greatly enjoyed the influence he could exercise over them. As a topflight journalist, he was always being made an editor of some magazine or daily, yet he hated a desk and four walls and - was no editor at all - except for his uncanny ability to think up assignments for himself and his love of scouting for young writers. He had gone to Harvard to ask Copeland for the names of some promising young men." Charles Townsend Copeland gave him the names of his two brightest students: John Reed and Walter Lippmann. Reed later wrote: "There are two men who gave me confidence in myself - Copeland and Steffens." In 1906 Steffens joined with the investigative journalists, Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker and William A. White to establish the radical American Magazine. Steffens's biographer, Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974), has argued: "That summer he and his partners celebrated their freedom from McClure's house of bondage, as they now saw it. There was a spirit of picnic and honeymoon about the enterprise; affections, loyalties, professional comradeship had never seemed quite so strong before and never would again. They dealt with each other as equals." Steffens later commented: "We were all to edit a writers' magazine." Steffens continued to write about corruption until 1910 when he went with John Reed to Mexico to report on Pancho Villa and his army. Steffens later recalled that Reed had "so much stuff that he didn't know how to write it, and I sat whole nights with him editing them into articles.... I showed him what he had." Steffens became a strong supporter of the rebels and during this period developed the view revolution, rather than reform, was the way to change capitalism. Harrison Gray Otis, the owner of the Los Angeles Times, was a leading figure in the fight to keep the trade unions out of Los Angeles. This was largely successful but on 1st June, 1910, 1,500 members of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers went on strike in an attempt to win a $0.50 an hour minimum wage. Otis, the leader of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association (M&M), managed to raise $350,000 to break the strike. On 15th July, the Los Angeles City Council unanimously enacted an ordinance banning picketing and over the next few days 472 strikers were arrested. On 1st October, 1910, a bomb exploded by the side of the newspaper building. The bomb was supposed to go off at 4:00 a.m. when the building would have been empty, but the clock timing mechanism was faulty. Instead it went off at 1.07 a.m. when there were 115 people in the building. The dynamite in the suitcase was not enough to destroy the whole building but the bombers were not aware of the presence of natural gas main lines under the building. The blast weakened the second floor and it came down on the office workers below. Fire erupted and spread quickly through the three-story building, killing twenty-one of the people working for the newspaper. The next day unexploded bombs were found at the homes of Harrison Gray Otis and of F. J. Zeehandelaar, the secretary of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association. The historian, Justin Kaplan, has pointed out: "Harrison Gray Otis accused the unions of waging warfare by murder as well as terror.... In editorials that were echoed and amplified across a country already fearful of class conflict, Otis vowed that the supposed dynamiters, who had committed the 'Crime of the Century,' must surely hang and the labor movement in general." William J. Burns, the detective who had been highly successful working in San Francisco, was employed to catch the bombers. Otis introduced Burns to Herbert S. Hockin, a member of the union executive who was a paid informer of the (M&M). Information from Hockin resulted in Burns discovering that union member Ortie McManigal had been handling the bombing campaign on orders from John J. McNamara, the secretary-treasurer of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers. McManigal was arrested and Burns convinced him that he had enough evidence to get him convicted of the Los Angeles Times bombing. McManigal agreed to tell all he knew in order to secure a lighter prison sentence, and signed a confession implicating McNamara and his brother, James B. McNamara. Other names on the list included Frank M. Ryan, president of the Iron Workers Union. According to Ryan the list named "nearly all those who have served as union officers since 1906." Some believed that it was another attempt to damage the reputation of the emerging trade union movement. It was argued that Harrison Gray Otis and his agents had framed the McNamaras, the object being to cover up the fact that the explosion had really being caused by leaking gas. Charles Darrow, who had successfully defended, William Hayward, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), when he had been falsely charged with the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, in 1906, was employed by Samuel Grompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, to defend the McNamara brothers. One of Darrow's assistants was Job Harriman, a former preacher turned lawyer. Steffens went to see John J. McNamara and James B. McNamara in prison: "There were J. B. McNamara, who was charged with actually placing and setting off the dynamite in Ink Alley that blew up part of the Times building and set fire to the rest, bringing about the death of twenty-one employees, and J. J. McNamara, J. B.'s brother, who was indicted on some twenty counts for assisting at explosions as secretary of the Structural Iron Workers' Union, directing the actual dynamiters. He was supposed in labor circles to be the commanding man, the boss; he looked it; a tall, strong, blond, he was a handsome figure of health and personal power. But his brother, Jim, who looked sick and weak, soon appeared as the man of decision. I had never met them before, but when they came out of their cells they greeted and sat down beside me as if I were an old friend." On 19th November 1911, Lincoln Steffens and Charles Darrow was asked to meet with Edward Willis Scripps at his Miramar ranch in San Diego. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Darrow arrived at Miramar with the sure prospect of defeat. He had failed, in his own investigations, to breach the evidence against the McNamaras; on his own, he had even turned up fresh evidence against them; and, in desperation, hoping for a hung jury and a mistrial.... Steffens, who had interviewed the McNamaras in their cell that week, asking for permission to write about them on the assumption that they were guilty; he had even talked to them about changing their plea. Darrow, too, was approaching the same stage in his reasoning. It was tragic, he had to agree with the other two, that the case could not be tried on its true issues, not as murder, but as a 'social crime' that was in itself an indictment of a society in which men believed they had to destroy life and property in order to get an hearing." Scripps suggested that the McNamaras had committed a selfless act of insurgency in the unequal warfare between workers and owners; after all, what weapons did labour have in this warfare except "direct action". The McNamaras were as "guilty" as John Brown had been guilty at Harper's Ferry. Scripps argued that "Workingmen should have the same belligerent rights in labour controversies that nations have in warfare. There had been war between the erectors and the ironworkers; all right, the war is over now; the defeated side should be granted the rights of a belligerent under international law." Steffens agreed with Scripps and suggested that the "only way to avert class struggle was to offer men a vision of society founded on the Golden Rule and on faith in the fundamental goodness of people provided that they were given half a chance to be good". Steffens offered to try and negotiate a settlement out of court. Darrow accepted the offer as he valued Steffens for "his intelligence and tact, and his acquaintance with people on both sides". This involved Steffens persuading the brothers to plead guilty. Steffens later wrote: "I negotiated the exact terms of the settlement. That is to say, I was the medium of communication between the McNamaras and the county authorities". Steffens met with the district attorney, John D. Fredericks. It was agreed the brothers would change their plea to guilty but offer no confession; the state would withdraw its demand for the death penalty, agree to impose only moderate prison terms, and also agree that there would be no further pursuit of other suspects in the case. On 5th December, 1911, Judge Walter Bordwell sentenced James B. McNamara to life imprisonment at San Quentin. His brother, John J. McNamara, who could not be directly linked to the Los Angeles Times Bombing, received a 15 year sentence. Bordwell denounced Steffens for his peacemaking efforts as "repellent to just men" and concluded: "The duty of the court in fixing the penalties in these cases would have been unperformed had it been swayed in any degree by the hypocritical policy favoured by Mr. Steffens (who by the way is a professed anarchist) that the judgment of the court should be directed to the promotion of compromise in the controversy between capital and labour." As he left the court James McNamara said to Steffens: "You see, you were wrong, and I was right". Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974) has pointed out: "Steffens' principled intervention proved to be a disaster, and to the end of his life he worked to secure a pardon or parole for the McNamaras and, by extension, for himself... He had wholly misjudged the ferocity of the opposed forces." Steffens told his sister: "What I am really up to is to make people think. I am challenging the modern ideals... The McNamara incident was simply a very successful stroke in this policy. It was like a dynamite explosion. It hurt." Steffens idea of the Golden Rule (a faith in the fundamental goodness of people) was much attacked by radicals. The militant union leader, Olav Tveitmoe, commented: "I will show him (Steffens) there is no Golden Rule, but there is a Rule of Gold". Emma Goldman also attacked Steffens for his approach to the case and what she called "the appalling hollowness of radicalism in the ranks in and out of the ranks of labour, and the craven spirit of so many of those who presume to plead its cause." Max Eastman, editor of The Masses, suggested that Steffens should have been transmitting his "kindly and disastrous sentiments" about practical Christianity to a Sunday-school class instead of to the courts. Ella Winter explained in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "The labor movement was nonplused and infuriated, for despite the concession Stef had wrung from judge and employers of relatively light sentences and no castigation from the Bench, J. B. was given life and John J. fifteen years - and a sizzling indictment from the Bench. Stef was reviled and mocked, attacked by friend and enemy. His protégé, Jack Reed, wrote a satiric poem called Sangar, jeering at Steffens' naïveté. Stef had described to me the trunkfulls of denunciations that reached him; from then on, no magazine would publish him. I had the impression that he never ceased to feel a certain self-reproach, and he had worked tirelessly for the men's release." In 1911 Steffens took Walter Lippmann on as his secretary. "I found Lippmann, saw right away what his classmates saw in him. He asked me intelligent, not practical, questions about my proposition and when they were answered, gave up the job he had and came home to New York to work with me on my Wall Street series of articles... Keen, quiet, industrious, he understood the meaning of all that he learned; and he asked the men he met for more than I asked him for." Steffens often visited the home of Mabel Dodge at 23 Fifth Avenue. Mabel's friend, Bertram D. Wolfe, later recalled: "Wealthy, gracious, open-hearted, beautiful, intellectually curious, and quite without a sense of discrimination, she was Bohemia's most successful lion-hunter." Her apartment in New York City became a place where intellectuals and artists met. This included John Reed, Robert Edmond Jones, Margaret Sanger, Louise Bryant, Bill Haywood, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, Frances Perkins, Amos Pinchot, Frank Harris, Charles Demuth, Andrew Dasburg, George Sylvester Viereck, John Collier, Carl Van Vechten and Amy Lowell. In his book, Autobiography (1931), Steffens claimed: "Mabel Dodge, who is, in her odd way, one of the most wonderful things in the world; an aristocratic, rich, good-looking woman, she has never set foot on the earth earthy... With taste and grace, the courage of inexperience, and a radiating personality, that woman has done whatever it has struck her fancy to do, and put it and herself over-openly. She never knew that society could and did cut her; she went ahead, and opening her house, let who would come to her salon. Her house was a great old-fashioned apartment on lower Fifth Avenue. It was filled full of lovely, artistic things; she dressed beautifully in her own way.... Mabel Dodge managed her evenings, and no one felt that they were managed. She sat quietly in a great armchair and rarely said a word; her guests did the talking, and with such a variety of guests, her success was amazing." While reporting on the Versailles Peace Conference, Steffens met Ella Winter, who worked for Felix Frankfurter. She later recalled: "The man was not tall, but he had a striking face, narrow, with a fringe of blond hair, a small goatee, and very blue eyes, and he stood there smiling. The face had wonderful lines... There was something devilish - or was it impish? - in the way this figure stood grinning at me." He wrote in Autobiography (1931): "When the peace-making was over and she returned to London, I visited her and eased her anxious parents by showing them that, to me, she was only youth." In January, 1919, Steffens and his friend, William Christian Bullitt, assistant secretary of state, argued that they should be sent to Russia to open up negotiations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Steffens said to Edward House: "You are fighting them, hating them... What for? Why, if you want to deal with them, don't you do as you would to any other government." Permission was granted by Secretary of State Robert Lansing on 18th February. Lansing wrote: "You are hereby directed to proceed to Russia for the purpose of studying conditions, political and economic, therein, for the benefit of the American Commissioners plenipotentiary to negotiate peace." Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Bullitt appointed as an unofficial member of the mission Lincoln Steffens, a known Bolshevik sympathizer and publicist. Bullitt's superiors might be outraged by the choice, but his reasoning at this point was unanswerable: he needed Steffens to vouch for him. American and British expeditory forces were fighting on the counter-revolutionary side in Russia; as far as Lenin's government was concerned the West had already declared war... The Russians trusted Steffens, knew that he was on their side and that he believed they were there to stay... As they left Paris, Bullitt and Steffens believed that they had been presented with a unique opportunity to make history by mediating between the West and the revolution." Steffens and Bullitt had a meeting with Lenin in Petrograd on 14th March. Lenin later commented that Bullitt was a young man of great heart, integrity, and courage". It was agreed that the Red Army would leave "Siberia, the Urals, the Caucasus, the Archangel and Murmansk regions, Finland, the Baltic states, and most of the Ukraine" as long as an agreement was signed by 10th April. However, the idea was rejected by President Woodrow Wilson and David Lloyd George. Bullitt and Steffens had a meeting with Lenin in Petrograd on 14th March. Lenin later commented that Bullitt was a young man of great heart, integrity, and courage". It was agreed that the Red Army would leave "Siberia, the Urals, the Caucasus, the Archangel and Murmansk regions, Finland, the Baltic states, and most of the Ukraine" as long as an agreement was signed by 10th April. Steffens later commented: "It was a disappointing return diplomatically. Bullitt had set his heart on the acceptance of his report; House was enthusiastic, and Lloyd George received him immediately at breakfast the second day and listened and was interested. Of course. Bullitt had brought back all the prime minister had asked.... No action was taken on the proposal Bullitt had brought back from Moscow, and after a few weeks of futile discussion the Bullitt mission was repudiated. I heard that the French, having got wind of it, challenged Lloyd George; he and Wilson had gone back of the French to negotiate with the Russians, they charged. And Lloyd George took the easiest way out. He denied Bullitt in Paris, and when there were inquiries in London, he crossed the Channel to appear before the House of Commons... Bullitt tried to appeal to President Wilson. When Wilson would not see him." After the terms of the Versailles Peace Conference was published Bullitt resigned in protest. He considered a betrayal of the men who had died during the First World War. On 17th May he wrote to President Woodrow Wilson, stating bitterly: "I am sorry that you did not fight our fight to the finish, and that you had so little faith in the millions of men, like myself, in every nation who had faith in you." Bullitt appeared before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and his testimony helped cause the treaty to be defeated in the Senate and the resignation of Robert Lansing. Steffens managed to get an interview with Lenin who he believed was a tolerant man until he was shot by Dora Kaplan: : "Lenin was impatient with my liberalism, but he had shown himself a liberal by instinct. He had defended liberty of speech, assembly, and the Russian press for some five to seven months after the October revolution which put him in power. The people had stopped talking; they were for action on the program. But the plottings of the whites, the distracting debates and criticisms of the various shades of reds, the wild conspiracies and the violence of the anarchists against Bolshevik socialism, developed an extreme left in Lenin's party which proposed to proceed directly to the terror which the people were ready for. Lenin held out against them till he was shot, and even then, when he was in hospital, he pleaded for the life of the woman who shot him." When he returned to the United States he said to Bernard Baruch, "I have seen the future and it works." Steffens admitted that "it was harder on the real reds than it was on us liberals". For example Emma Goldman, told him that she was strongly opposed to the communist government. "Emma Goldman, the anarchist who was deported to that socialist heaven, came out and said it was hell. And the socialists, the American, English, the European socialists, they did not recognize their own heaven. As some will put it, the trouble with them was that they were waiting at a station for a local train, and an express tore by and left them there. My summary of all our experiences was that it showed that heaven and hell are one place, and we all go there. To those who are prepared, it is heaven; to those who are not fit and ready, it is hell." Steffens was one of those people who campaigned for Eugene Debs to be released from prison. In 1921 he had a meeting with Warren G. Harding: "After he had been in office awhile I went to him with a similar proposition, and to be sure of my ground, I sounded first a small number of governors to see if they would join in a general act of clemency for war and labor prisoners. Right away I got the reaction familiar to me: the politician governors would pardon their prisoners if the president would pardon his; the better men, the good, business governors, were most unwilling." President Harding pardoned Debs in December, 1921. Whenever Steffens came to London he spent a great deal of time with Ella Winter. She became increasingly radicalised during this period. A visit from Marion Phillips, who was now a senior figure in the Labour Party, ended up in a heated discussion about the Russian Revolution. Winter later described the incident: "When the conversation turned to the Russian Revolution and Bolshevism, the evening, to my dismay, exploding into astonishing hostility and bitterness from Marion Phillips. Like the official Labour Party, she was implacably opposed to the Russian Revolution, but it did not occur to me that her enmity and personal rudeness may have been partly due to her realization that she was losing me." In 1924 Ella agreed to live with Steffens, thirty-two years her senior. They moved to Paris and spent some time with William Christian Bullitt and Louise Bryant, who had just got married. Bryant was the widow of John Reed. Winter later wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "We saw much of Louise Bryant and Billy Bullitt, Louise very pregnant in an Arabian Nights maternity gown of black and gold that I thought could have been worn by a Persian queen. Billy hovered over her like a mother hen." A daughter, Anne Moen Bullitt, was born in 24th February, 1924. The couple also spent time with Ernest Hemingway, a young writer he discovered. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Among the younger men Steffens saw in Paris, Ernest Hemingway appeared to him to have the surest future, the most buoyant confidence, and the best grounds for it." Steffens told Ella Winter: "He's fascinated by cablese, sees it as a new way of writing." Winter explained: "Stef loved anything new, original, or experimental, and he especially cherished young people. He was sending Hemingway's stories to American magazines, and they were coming back, but this did not alter his opinion." Steffens told anyone who would listen: "Someone will recognize that boy's genius and then they'll all rush to publish him." Ella Winter became pregnant. She later explained, "Steff wanted the baby, but not to be again a married man... Illegitimacy, so dread a concept to me, meant nothing to him; in fact, he regarded it as rather an advantage." He argued "love-children have always been the best, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Erasmus" and added "I'm an anarchist, I don't want the law to dictate to me." However, he changed his mind and they married in Paris when she was six months pregnant. Their son Pete Steffens was born in San Romeo, in 1924. By this stage of his career Steffens had great difficulty finding magazines willing to publish his work. He believed it was because he had campaigned against the imprisonment of James McNamara and Joseph McNamara, convicted of the Los Angeles Times Bombing. Steffens complained: "Editors are afraid of me since I took the McNamaras' part ten years ago. I was condemned by everybody." He wrote an article, Oil and Its Political Implications , that he was very pleased with but could not find a publisher for it. He told Ella, "I don't seem able to state my truths so that they'll be accepted. I must find a new form." Although they did not want his articles several publishers had offered him contracts to write his autobiography. He had talked about it, but the job seemed too vast. Steffens was also a perfectionist. According to Ella he "wrote on small pad pages by hand, wrote and rewrote" unwilling to leave a paragraph "until the prose sings". He insisted that "I can't leave a paragraph until it's perfect. That's how I trained myself to write." In 1927 Steffens and Winter moved to the U.S. and settled in Carmel, California (Winter became a naturalized American citizen in 1929). Winter wrote: "Carmel had been created when a real-estate man decided to enhance the value of the land by developing it and offering free lots to any artist who would build. Among early settlers were George Sterling, the California poet, Jack London, Mary Austin, Ambrose Bierce... Now Carmel was an artists' colony, with painters, writers, musicians, photographers living in little wooden or stone cottages." During this period Winter and Steffens befriended a number of artists, journalists, and political figures, including Albert Rhys Williams, John Steinbeck, Robinson Jeffers, Harry Leon Wilson and Marie de L. Welch. Steffens's memoirs, Autobiography, was published in April 1931. It was a great success and as Ella Winter has pointed out: "He had to talk everywhere, at bookshops, lunches, meetings, and autograph copies even for the salesgirls in bookstores... I couldn't help feeling proud. The six years' doubts, agonies, despairs had their reward. I felt Stef had done what he sought to do, showed in a wealth of anecdote and incident what he had learned and unlearned in the course of his life... He had told the stories he had been telling me for years and which had so opened my eyes." Steffens told Ella: "I guess I'm a success. I guess I'll go down in history now." According to Winter, William Randolph Hearst offered Steffens the chance "to do a syndicated column for a large sum and a circulation of twenty-four million, but Steffens refused." Instead he worked for a newspaper, The Carmelite , established by his wife. Steffens commented: "I'd rather say what I want to for nothing and a circulation of three hundred." Ella Winter went to interview Harry Bridges during the waterfront strike in 1934: "In San Francisco I went first to the longshoremen's headquarters on the Embarcadero and found Harry Bridges, the voluble and tough union leader, a wire spring of a man with a narrow, sharp-featured, expressive face, popping eyes, and strong Australian accent. He heartily greeted a fellow Australian, a limey, as he dubbed me, though I was a little taken aback at my first real taste of a worker's intemperate language." Bridges told her that previous strikes had been crushed and a company union set up: "The seamen couldn't get together because they were divided into so many crafts, machinists, cooks, stewards, ships' scalers, painters, boilermakers, the warehousemen on the docks, and the teamsters who hauled the goods. The bosses want to keep it that way so they can make separate contracts for each craft and in each port, which weakens our bargaining position. We're asking for one coastwise contract, from Portland to San Pedro, for the whole industry, and a raise too, but the most important thing we want is a hiring hall under the men's control." Steffens also supported the strikers. On 19th July 1934 he wrote to Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor: "There is hysteria here, but the terror is white, not red. Business men are doing in this Labor struggle what they would have liked to do against the old graft prosecution and other political reform movements, yours included... Let me remind you that this widespread revolt was not caused by aliens. It takes a Chamber of Commerce mentality to believe that these unhappy thousands of American workers on strike against conditions in American shipping and industry are merely misled by foreign Communist agitators. It's the incredibly dumb captains of industry and their demonstrated mismanagement of business that started and will not end this all-American strike and may lead us to Fascism." Peter Hartshorn, the author of I Have Seen the Future: A Life of Lincoln Steffens (2011), has argued: "The final agreement saw concessions made by both sides, with the result being the continued emergence of an organized labor voice in California and nationwide, an achievement in which Steffens took some consolation. Perkins herself did not ignore Steffens, inviting him the following year to attend a San Francisco meeting of West Coast leaders." In 1935 Steffens gave his name in support of the American Writers' Congress to be held in New York City. Its main objective was to give support to those fighting Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Europe. Steffens wrote that he did not mind the movement being led by the American Communist Party: "I don't want the Republicans or the Democrats or us Liberals or Upton Sinclair or myself to lead it... We all will stop a revolution as we do a reform, as we always have stopped everything when we have got enough. And we always have so much graft, property, privileges - what you like - that we will get enough too soon, before we have got enough for all, before we have got all. In every revolution in history men have cried enough, when they got enough. This time we must go on until we have all." Steffens continued to help young writers. He wrote to his friend, Sam Darcy on 25th February, 1936, about the work of John Steinbeck and his novel, In Dubious Battle: "His novel is called In Dubious Battle, the story of a strike in an apple orchard. It's a stunning, straight, correct narrative about things as they happen. Steinbeck says it wasn't undertaken as a strike or labor tale and he was interested in some such theme as the psychology of a mob or strikers, but I think it is the best report of a labor struggle that has come out of this valley. It is as we saw it last summer. It may not be sympathetic with labor, but it is realistic about the vigilantes." Lincoln Steffens, aged seventy, became very ill that summer. He was diagnosed as suffering from arteriosclerosis, but refused to leave his home in Carmel, California. He told his doctor: "I'd rather die sooner than leave my own home". He died on 9th August 1936. According to Ella Winter his last words were "No, no. I can't..."New York Evening Post

The Shame of the Cities

Los Angeles Times Bombing

Walter Lippmann

The Russian Revolution

Ella Winter

Carmel

American Writers' Congress

Primary Sources

(1) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

It is possible to get an education at a university. It has been done; not often, but the fact that a proportion, however small, of college students do get a start in interested, methodical study, proves my thesis, and the two personal experiences I have to offer illustrate it and show how to circumvent the faculty, the other students, and the whole college system of mind-fixing. My method might lose a boy his degree, but a degree is not worth so much as the capacity and the drive to learn, and the undergraduate desire for an empty baccalaureate is one of the holds the educational system has on students. Wise students some day will refuse to take degrees, as the best men (in England, for instance) give, but do not themselves accept, titles.

My method was hit on by accident and some instinct. I specialized. With several courses prescribed, I concentrated on the one or two that interested me most, and letting the others go, I worked intensively on my favorites. In my first two years, for example, I worked at English and political economy and read philosophy. At the beginning of my junior year I had several cinches in history. Now I liked history; I had neglected it partly because I rebelled at the way it was taught, as positive knowledge unrelated to politics, art, life, or anything else. The professors gave us chapters out of a few books to read, con, and be quizzed on. Blessed as I was with a "bad memory," I could not commit to it anything that I did not understand and intellectually need. The bare record of the story of man, with names, dates, and irrelative events, bored me. But I had discovered in my readings of literature, philosophy, and political economy that history had light to throw upon unhistorical questions. So I proposed in my junior and senior years to specialize in history, taking all the courses required.

(2) Joseph Steffens, letter to his son, Lincoln Steffens (1892)

My dear son: When you finished school you wanted to go to college. I sent you to Berkeley. When you got through there, you did not care to go into my business; so I sold out. You preferred to continue your studies in Berlin. I let you. After Berlin it was Heidelberg; after that Leipzig. And after the German universities you wanted to study at the French universities in Paris. I consented, and after a year with the French, you had to have half a year of the British Museum in London. All right. You had that too.

By now you must know about all there is to know of the theory of life, but there's a practical side as well. It's worth knowing. I suggest that you learn it, and the way to study it, I think, is to stay in New York and hustle.

Enclosed please find one hundred dollars, which should keep you till you can find a job and support yourself.

(3) Lincoln Steffens and Claude Wetmore, McClure's Magazine (October, 1902)

Go to St. Louis and you will find the habit of civic pride in them; they still boast. The visitor is told of the wealth of the residents, of the financial strength of the banks, and of the growing importance of the industries; yet he sees poorly paved, refuse-burdened streets, and dusty or mud-covered alleys; he passes a ramshackle firetrap crowded with the sick and learns that it is the City Hospital: he enters the Four Courts, and his nostrils are greeted with the odor of formaldehyde used as a disinfectant and insect powder used to destroy vermin; he calls at the new City Hall and finds half the entrance boarded with pine planks to cover up the unfinished interior. Finally, he turns a tap in the hotel to see liquid mud flow into wash basin or bathtub.

(4) Lincoln Steffens, McClure's Magazine (January, 1903)

Whenever anything extraordinary is done in American municipal politics, whether for good or for evil, you can trace it almost invariably to one man. The people do not do it. Neither do the "gangs", "combines", or political parties. These are but instruments by which bosses (not leaders; we Americans are not led, but driven) rule the people, and commonly sell them out. But there are at least two forms of the autocracy which has supplanted the democracy here as it has everywhere it has been tried. One is that of the organized majority by which, as in Tammamy Hall in New York and the Republican machine in Philadelphia, the boss has normal control of more than half the voters. The other is that of the adroitly managed minority. The "good people" are herded into parties and stupefied with convictions and a name, Republican or Democrat; while the "bad people" are so organized or interested by the boss that he can wield their votes to enforce terms with party managers and decide elections. St. Louis is a conspicuous example of this form. Minneapolis is another.

(5) Lincoln Steffens, The Struggle for Self-Government (1906)

"They" say in Wisconsin that La Follette is a demagogue, and if it is , demagogy to go thus straight to the voters, then "they" are right. But then Folk also is a demagogue, and so are all thoroughgoing reformers. La Follette from the beginning has asked, not the bosses, but the people for what he wanted, and after 1894 he simply broadened his field and redoubled his efforts. He circularized the State, he made speeches every chance he got, and it the test of demagogy is the tone and style of a man's speeches, La Follette is the opposite of a demagogue. Capable of fierce invective, his oratory is impersonal; passionate and emotional himself, his speeches are temperate. Some of them are so loaded with facts and such closely knit arguments that they demand careful reading, and their effect is traced to his delivery, which is forceful, emphatic, and fascinating.

(6) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

The mayor of New York, Seth Low, was a business man and the son of a business man, rich, educated, honest, and trained to his political job. Seth Low and his party in power and his backers were not radicals in any sense. Mr. Low himself was hardly a liberal; he was what would be called in England a conservative. He accepted the system; he took over the government as generations of corrupters had made it, and he was trying, without any fundamental change, and made it an efficient, orderly business-like organization for the protection and the furtherance of all business, private and public.

(7) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

Governor La Follette was a powerful man, who, short but solid, swift and willful in motion, in speech, in decision, gave the impression of a tall, a big, man. He had meant to be an actor; he was one always. His lines were his own, but he consciously, artfully recited them well and for effect which, like an artist, he calculated. But what I saw at my first sight of him was a sincere, ardent man who, whether standing, sitting, or in motion, but the grace of trained strength, both physical and mental.

Bob La Follette was called a little giant. Rather short in stature, but broad and strong, he had the gift of muscled, nervous power, he kept himself in training all his life. His sincerity, his integrity, his complete devotion to his ideal, were indubitable; no one who heard could suspect his singleness of purpose or his courage. The strange contradictions in him were that he was a fighter - for peace; he battered his fist so terribly in one great speech for peace during the World War that he had to be treated and then carried it in bandages for weeks.

(8) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

The gift of the gods to Theodore Roosevelt was joy, joy in life. He took joy in everything he did, in hunting, camping, and ranching, in politics, in reforming the police or the civil service, in organizing and commanding the Rough Riders.

A tragedy in his life was President Wilson's refusal to give him and General Wood commands in France, and I think that he enjoyed his hate of Wilson; he expressed it so well; he indulged it so completely. Yes, I think that he took joy in his utterly uncurbed loathing for the Great War president.

(9) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

Hearst, in journalism, was like a reformer in politics; he was an innovator who was crashing into the business, upsetting the settled order of things, and he was not doing it as we would have done it (The American Magazine). He was doing it his way. I thought that Hearst was a great man, able, self-dependent, self-educated (though he had been to Harvard) and clear-headed; he had no moral illusions; he saw straight as far as he saw, and he saw pretty far, further than I did then; and, studious of the methods which he adopted after experimentation, he was driving toward his unannounced purpose: to establish some measure of democracy, with patient but ruthless force.

(10) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

Lenin was impatient with my liberalism, but he had shown himself a liberal by instinct. He had defended liberty of speech, assembly, and the Russian press for some five to seven months after the October revolution which put him in power. The people had stopped talking; they were for action on the program. But the plottings of the whites, the distracting debates and criticisms of the various shades of reds, the wild conspiracies and the violence of 'the anarchists against Bolshevik socialism, developed an extreme left in Lenin's party which proposed to proceed directly to the terror which the people were ready for. Lenin held out against them till he was shot, and even then, when he was in hospital, he pleaded for the life of the woman who shot him.

I referred to this, and he acknowledged it and said: "It was no use. It is no use. There will be a terror. It hurts the revolution both inside and out, and we must find out how to avoid or control or direct it. But we have to know more about psychology than we do now to steer through that madness. And it serves a purpose that has to be served. There must be in a revolution, as in a war, unified action, and in a revolution more than in a war the contented people will scuttle your ship if you don't deal with them. There are white terrors, too, you know. Look at Finland and Hungary. We have to devise some way to get rid of the bourgeoisie, the upper classes. They won't let you make economic changes during a revolution any more than they will before one; so they must be driven out. I don't see, myself, why we can't scare them away without killing them. Of course they are a menace outside as well as in, but the emigres are not so bad. The only solution I see is to have the threat of a red terror spread the fear and let them escape. But however it is done, it has to be done. The absolute, instinctive opposition of the old conservatives and even of the fixed liberals has to be silenced if you are to carry through a revolution to its objective."

He foresaw trouble with the fixed minds of the peasants, their hard conservatism, and his remark reminded me of the land problem. They were giving the peasants land? "Not by law," he said. "But they think they own the land; so they do."

He took a piece of paper and a pencil. "We are all wrong on the land," he said, and the thought of Wilson flashed to my mind. Could the American say he was all wrong like that? "Look," said Lenin, and he drew a straight line. "That's our course, but"- he struck off a crooked line to a point "that's where we are. That's where we have had to go, but we'll get back here on our course some day." He paralleled the straight line.

That is the advantage of a plan. You can go wrong, you can tack, as you must, but if you know you are wrong, you can steer back on your course. Wilson, the American liberal, having justified his tackings, forgot his course. To keep himself right, he had changed his mind to follow his actions till he could call the peace of Versailles right. Lenin was a navigator, the other a mere sailor.

There was more of this rapid interview, but not words. When I came out of it, I found that I had fertile ideas in my head and an attitude which grew upon me. Events, both in Russia and out, seemed to have a key that was useful, for example, in Fascist Italy, in Paris, and at home in the United States. Our return from Moscow was less playful than the coming. Bullitt was serious. Captain Petit was interesting on the hunger and the other sufferings of Petrograd, but not depressed as he would have been in New York or London. "London's is an old race misery," he said. "Petrograd is a temporary condition of evil, which is made tolerable by hope and a plan." Arthur Ransome, the English correspondent of the Manchester Guardian, came out with us. He had been years in Russia, spoke Russian, and had spent the last winter in Moscow with the government leaders and among the people. He had the new point of view. He said and he showed that Shakespeare looked different after Russia, and, unlike some other authors, still true. Our journey home was a course of intellectual digestion; we were all enjoying a mental revolution which corresponded somewhat with the Russian Revolution and gave us the sense of looking ahead.

(11) Lincoln Steffens and Clarence Darrow met Edward Wyllis Scripps at his ranch near San Diego in 1911. Steffens wrote about the meeting in his autobiography published in 1931.

His (E. W. Scripps) hulking body, in big boots and rough clothes, carried a large grey head with a wide grey face which did not always express, like Darrow's, the constant activity of the man's brain. He was a hard student, whether he was working on newspaper make-up or some inquiry in biology. That mind was not to be satisfied. It read books and fed on the conversation of scientists, not to quench an inquiry with the latest information, but to excite and make intelligent the questions implied.

(12) In his autobiography Lincoln Steffens explains how he visited James and Joseph McNamara, who had been charged with the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building.

I spoke to Darrow, who gave me permission to see his clients, and that afternoon, when court adjourned, I called on them at the jail. There were J. B. McNamara, who was charged with actually placing and setting off the dynamite in Ink Alley that blew up part of the Times building and set fire to the rest, bringing about the death of twenty-one employees, and J. J. McNamara, J. B.'s brother, who was indicted on some twenty counts for assisting at explosions as secretary of the Structural Iron Workers' Union, directing the actual dynamiters. He was supposed in labor circles to be the commanding man, the boss; he looked it; a tall, strong, blond, he was a handsome figure of health and personal power. But his brother, Jim, who looked sick and weak, soon appeared as the man of decision. I had never met them before, but when they came out of their cells they greeted and sat down beside me as if I were an old friend.

(13) George Seldes, interviewed by Randolph T. Holhut (1992)

Lincoln Steffens was the godfather of us all. He was an older man when I first met him (in 1919). He was the first of the muckrakers. As he once said, "where there's muck, I'll rake it." He often warned me that I was starting to get a bad reputation for myself. I guess I never worried about that.

(14) Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism (1957)

If Steffens did not immediately go all the way to active participation in the Communist movement, the rest of the journey was traveled by his protege, John Reed.

Twenty-one years separated Steffens and Reed in age, and the younger man could start where the older one had left off. Steffens had been a friend of Reed's father, a prosperous Portland, Oregon, businessman. When Reed in his early twenties was making his way as a young journalist in New York, Steffens still enjoyed the full success of his muckraking fame. Yet Reed shot ahead so fast that, in a few short years, they were like contemporaries, going through the same experiences together. In 1911 Steffens enabled Reed, then twenty-four, to get his first journalistic job. Two years later, both of them were reporting Pancho Villa's uprising across the Mexican border, with Reed gaining most of the journalistic glory.

If John Reed had deliberately arranged his life to contradict all the future cliches about Communists, he could not have done a more thorough job. He was not an immigrant; his grandfather had been one of the pioneer builders of Portland. He was not an Easterner; he came from the Far Northwest. He was not a poor boy; he was born into wealth and privilege. He was not self-educated; he attended private schools and Harvard. He was not a revolutionary turned journalist; he was a journalist turned revolutionary. Not a little of the attraction Reed had for the majority of the poor, immigrant Communists may be attributed to what he was, as well as to what he did. Communism was more than a movement of social outcasts if it could attract someone like Reed.

(15) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

"So you've been over into Russia?" said Bernard Baruch, and I answered very literally, "I have been over into the future, and it works." This was in Jo Davidson's studio, where Mr. Baruch was sitting for a portrait bust. The sculptor asked if I wasn't glad to get back. I was. It was a mental change that we had experienced, not physical. Bullitt asked in surprise why it was that, having been so elated by the prospect of Russia, we were so glad to be back in Paris. I thought it was because, though we had been to heaven, we were so accustomed to our own civilization that we preferred hell. We were ruined; we could recognize salvation, but could not be saved.

And, by the way, it was harder on the real reds than it was on us liberals. Emma Goldman, the anarchist who was deported to that socialist heaven, came out and said it was hell. And the socialists, the American, English, the European socialists, they did not recognize their own heaven. As some will put it, the trouble with them was that they were waiting at a station for a local train, and an express tore by and left them there. My summary of all our experiences was that it showed that heaven and hell are one place, and we all go there. To those who are prepared, it is heaven; to those who are not fit and ready, it is hell.

It was a disappointing return diplomatically. Bullitt had set his heart on the acceptance of his report; House was enthusiastic, and Lloyd George received him immediately at breakfast the second day and listened and was interested. Of course. Bullitt had brought back all the prime minister had asked. And that same morning I was received and questioned, very intelligently, by "British information, Russian section." I had learned to despise the secret services; they were so un- and mis-informed; but these British officers knew and understood the facts. They asked me questions which only well-informed, comprehending, imaginative minds could have asked, and my news fitted into their picture. All a long forenoon they probed and discussed and understood so perfectly that when I was saying good-by at noon I begged leave to compliment them and to contrast their British information with our American secret service. And, by way of a true jest, I said to them: "You have proved to me that my government is honest and that yours is not."

"But why that?"

"Well," I said, "your government, like mine, talks lies, but evidently your government knows the truth. Mine does not. My government believes its own damned lies; yours doesn't."

No action was taken on the proposal Bullitt had brought back from Moscow, and after a few weeks of futile discussion the Bullitt mission was repudiated. I heard that the French, having got wind of it, challenged Lloyd George; he and Wilson had gone back of the French to negotiate with the Russians, they charged. And Lloyd George took the easiest way out. He denied Bullitt in Paris, and when there were inquiries in London, he crossed the Channel to appear before the House of Commons to declare explicitly and at length that he knew nothing of the "journey some boys were reported to have made to Russia." I have had it explained to me since that this is not so weak and wicked as it seemed to us. It was a political custom in British parliamentary practice to use young men for sounding or experimental purposes, and it was understood that if such a mission became embarrassing to the ministry, it was repudiated; the missionaries lay down and took the disgrace till later, when it was forgotten, they would get their reward. But Bullitt would not play this game. He tried to appeal to President Wilson. When Wilson would not see him I remembered the old promise to me after the Mexican affair to receive me if I should send in my name with the words, "It's an emergency." I did that, and my messenger, a man who saw the president every day, described the effect.

We offer best quality 640-802 dumps test papers and 646-364 materials. You can get our 100% guaranteed 640-822 questions & 642-611 to help you in passing the real exam of 642-654.

© John Simkin, April 2013