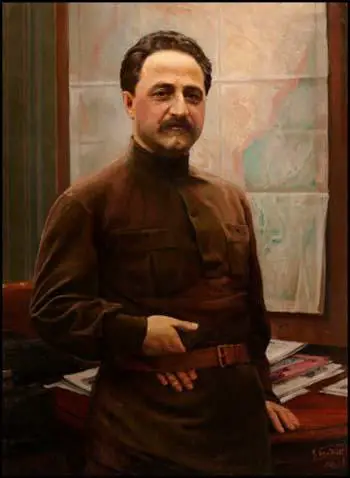

Sergo Ordzhonikidze

Sergo Ordzhonikidze, the son of a small landowner, was born in Georgia on 24th October 1886. He became a student at the Mikhailov Hospital Medical School in Tiflis where he became involved in radical politics.

In 1903 Ordzhonikidze joined the Social Democratic Party and supported the Bolshevik faction. Soon after graduating as a doctor, Ordzhonikidze was arrested for conveying arms. He was released and decided to live in Germany. He returned to Russia in 1907 and settled in Baku where he became friends with Joseph Stalin, Stepan Shaumyan, Kliment Voroshilov and Andrei Vyshinsky. Their leader, Lenin, went into exile with the words: "the revolutionary parties must complete their education. They had learnt how to attack... They had got to learn that victory was impossible... unless they knew both how to attack and how to retreat correctly."

Ordzhonikidze worked closely with his friends in developing the political consciousness of the workers in the region. The workers in the oil fields belonged to a union under the influence of the Bolsheviks. Stalin later wrote: "Two years of revolutionary work among the oil workers of Baku hardened me as a practical fighter and as one of the practical leaders. In contrast with advanced workers of Baku... in the storm of the deepest conflicts between workers and oil industrialists... I first learned what it meant to lead big masses of workers. There in Baku... I received my revolutionary baptism in combat."

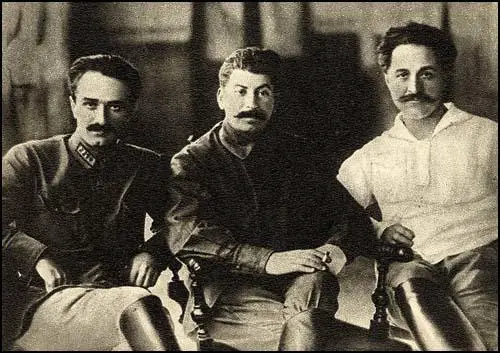

Sergo Ordzhonikidze and Stalin

Sergo Ordzhonikidze was elected as one of the delegates of the union involved in the negotiations with the employers. Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949), has pointed out: "The delegates' conference was in session for several months, debating every point in the collective agreements, controlling strikes, and airing its political views." Ordzhonikidze commented: "While all over Russia black reaction was reigning, a genuine workers' parliament was in session at Baku."

After eight months of work on the Baku committee, Ordzhonikidze and Stalin were caught by the Okhrana and put in prison. Deutscher claimed that: "Of the two spokesman for the Bolshevik prisoners, Stalin was cool, ruthless, and self-possessed, Ordzhonikidze touchy, exuberant, and ready to fly off at a tangent into riotous affray. The discussions were poisoned by suspicion - the Okhrana had planted its agents provocateurs even in the prison cells. Time and again the prisoners, roused to feverish suspicion, would try to trace them and, in some cases, they would kill a suspect, since the code of the underground allowed or even demanded the killing of agent provocateurs, as a measure of self-defence."

In November 1908 Ordzhonikidze and Stalin were deported to Solvychegodsk, in the northern part of the Vologda province on the Vychegda River. Both men eventually escaped and Ordzhonikidze went to live in Paris. He returned to St. Petersburg in February 1912, when Ordzhonikidze, Stalin, Elena Stasova and Roman Malinovsky were appointed to the Russian Party Bureau, on a salary of 50 rubles per month. What they did not know was that Malinovsky was being paid 500 rubles per month by Okhrana.

Adam B. Ulam, the author of Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007) has pointed out: "He was shadowed by the police as he was leaving Baku. On April 7 he was in Moscow, conferring with Ordzhonikidze and Malinovsky. But the two Georgians obviously could not be arrested in Moscow, for this would have thrown suspicion on Malinovsky, so they were allowed to leave for St. Petersburg on April 9 in the discreet company of three police agents. In the next few weeks the Bolsheviks' entire Russian Bureau was "busted." Ordzhonikidze was arrested on April 14, Stalin on April 22, then Spandaryan and Yelena Stasova, the Central Committee's new agent for the Caucasus." Ordzhonikidze was found guilty of being a member of an illegal organisation and was sentenced to three years' hard labour.

The Russian Revolution

After the overthrow of Nicholas II, the new prime minister, Prince Georgi Lvov, allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Joseph Stalin arrived at Nicholas Station in St. Petersburg with Lev Kamenev on 25th March, 1917. They were followed by Lenin in April. Ordzhonikidze arrived in June. On 10th October, 1917, Ordzhonikidze supported the resolution proposed by Lenin that the Central Committee prepared for an armed insurrection. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Alexander Kerensky had managed to escape from the city.

The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. The Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace and arrested the Cabinet ministers.

During the Russian Civil War Ordzhonikidze became Commissar for the Ukraine. He was involved in fighting at Tsaritsyn and the Caucasus. It has been claimed by Simon Sebag Montefiore that he was a "dashing, leonine hero, at home on horseback (he was accused of riding a white horse through conquered Tiflis)". A friend commented that "it seemed as if he had been born in his long military coat and boots". In 1920 he helped establish Soviet power in Armenia and Georgia.

In November, 1926, Joseph Stalin appointed Ordzhonikidze to the presidency of the Central Control Commission where he was given responsibility for expelling the Left Opposition from the Communist Party. Ordzhonikidze was rewarded by being appointed to the Politburo in 1926. He developed a reputation for having a terrible temper. His daughter said that he "often got so heated that he slapped his comrades but the eruption soon passed." His wife Zina argued "he would give his life for one he loved and shoot the one he hated". However, others said he had great charm and Maria Svanidze described him as "chivalrous". The son of Lavrenty Beria commented that his "kind eyes, grey hair and big moustache, gave him the look of an old Georgian prince".

Commissar for Heavy Industry

1932 he became Commissar for Heavy Industry. Yuri Piatakov, was appointed his deputy. The two men had the important task of making the Five Year Plan a success. The plan concentrated on the development of iron and steel, machine-tools, electric power and transport. Stalin demanded a 110% increase in coal production, 200% increase in iron production and 335% increase in electric power. He justified these demands by claiming that if rapid industrialization did not take place, the Soviet Union would not be able to defend itself against an invasion from capitalist countries in the west.

Every factory had large display boards erected that showed the output of workers. Those that failed to reach the required targets were publicity criticized and humiliated. Some workers could not cope with this pressure and absenteeism increased. This led to even more repressive measures being introduced. Records were kept of workers' lateness, absenteeism and bad workmanship. If the worker's record was poor, he was accused of trying to sabotage the Five Year Plan and if found guilty could be shot or sent to work as forced labour on the Baltic Sea Canal or the Siberian Railway.

Martemyan Ryutin

In the summer of 1932 Martemyan Ryutin wrote a 200 page analysis of Stalin's policies and dictatorial tactics, Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship. Ryutin argues: "The party and the dictatorship of the proletariat have been led into an unknown blind alley by Stalin and his retinue and are now living through a mortally dangerous crisis. With the help of deception and slander, with the help of unbelievable pressures and terror, Stalin in the last five years has sifted out and removed from the leadership all the best, genuinely Bolshevik party cadres, has established in the VKP(b) and in the whole country his personal dictatorship, has broken with Leninism, has embarked on a path of the most ungovernable adventurism and wild personal arbitrariness."

Ryutin then went onto making a very personal attack on Stalin: "To place the name of Stalin alongside the names of Marx, Engels and Lenin means to mock at Marx, Engels and Lenin. It means to mock at the proletariat. It means to lose all shame, to overstep all hounds of baseness. To place the name of Lenin alongside the name of Stalin is like placing Mt. Elbrus alongside a heap of dung. To place the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin alongside the works of Stalin is like placing the music of such great composers as Beethoven, Mozart, Wagner and others alongside the music of a street organ grinder... Lenin was a leader but not a dictator. Stalin, on the contrary, is a dictator but not a leader."

Ryutin did not only blame Stalin for the problems facing the Soviet Union: "The entire top leadership of the Party leadership, beginning with Stalin and ending with the secretaries of the provincial committees are, on the whole, fully aware that they are breaking with Leninism, that they are perpetrating violence against both the Party and non-Party masses, that they are killing the cause of socialism. However, they have become so tangled up, have brought about such a situation, have reached such a dead-end, such a vicious circle, that they themselves are incapable of breaking out of it... The mistakes of Stalin and his clique have turned into crimes.... In the struggle to destroy Stalin's dictatorship, we must in the main rely not on the old leaders but on new forces. These forces exist, these forces will quickly grow. New leaders will inevitably arise, new organizers of the masses, new authorities. A struggle gives birth to leaders and heroes. We must begin to take action."

John Archibald Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, the authors of The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (2010) have argued: "This manifesto of the Union of Marxist-Leninists was a multifaceted, direct, and trenchant critique of virtually all of Stalin's policies, his methods of rule, and his personality. The Ryutin Platform, drafted in March, was discussed and rewritten over the next few months. At an underground meeting of Ryutin's group in a village in the Moscow suburbs on 21 August 1932, the document was finalized by an editorial committee of the Union.... At a subsequent meeting, the leaders decided to circulate the platform secretly from hand to hand and by mail. Numerous copies were made and circulated in Moscow, Kharkov, and other cities. It is not clear how widely the Ryutin Platform was spread, nor do we know how many party members actually read it or even heard of it. The evidence we do have, however, suggests that the Stalin regime reacted to it in fear and panic."

Stalin interpreted Ryutin's manifesto as a call for his assassination. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Stalin also attacked those who were calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. The Leningrad Party chief, Sergy Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. Ordzhonikidze also agreed with Kirov. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin. It is claimed that Stalin never forgave Ordzhonikidze and Kirov for this betrayal.

On 22nd September, 1932, Martemyan Ryutin was arrested and held for investigation. During the investigation Ryutin admitted that he had been opposed to Stalin's policies since 1928. On 27th September, Ryutin and his supporters were expelled from the Communist Party. Ryutin was also found guilty of being an "enemy of the people" and was sentenced to a 10 years in prison. Soon afterwards Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were expelled from the party for failing to report the existence of Ryutin's report. Ryutin and his two sons, Vassily and Vissarion were later both executed.

Sergy Kirov

At the 17th Party Congress in 1934, when Sergy Kirov stepped up to the podium he was greeted by spontaneous applause that equalled that which was required to be given to Joseph Stalin. In his speech he put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. The members of the Congress gave Kirov a vote of confidence by electing him to the influential Central Committee Secretariat.

Stalin now found himself in a minority in the Politburo. After years of arranging for the removal of his opponents from the party, Stalin realized he still could not rely on the total support of the people whom he had replaced them with. Stalin no doubt began to wonder if Kirov was willing to wait for his mentor to die before becoming leader of the party. Stalin was particularly concerned by Kirov's willingness to argue with him in public. He feared that this would undermine his authority in the party.

As usual, that summer Kirov and Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé. According to Alexander Orlov, who had been told this by Genrikh Yagoda, Stalin decided that Kirov had to die.

Yagoda assigned the task to Vania Zaporozhets, one of his trusted lieutenants in the NKVD. He selected a young man, Leonid Nikolayev, as a possible candidate. Nikolayev had recently been expelled from the Communist Party and had vowed his revenge by claiming that he intended to assassinate a leading government figure. Zaporozhets met Nikolayev and when he discovered he was of low intelligence and appeared to be a person who could be easily manipulated, he decided that he was the ideal candidate as assassin.

Zaporozhets provided him with a pistol and gave him instructions to kill Kirov in the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. However, soon after entering the building he was arrested. Zaporozhets had to use his influence to get him released. On 1st December, 1934, Nikolayev, got past the guards and was able to shoot Kirov dead. Nikolayev was immediately arrested and after being tortured by Genrikh Yagoda he signed a statement saying that Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev had been the leaders of the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov.

Lavrenti Beria

In 1936 Lavrenti Beria started plotting against Ordzhonikidze. According to Adam B. Ulam, the author of Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007): "In Party circles Ordzhonikidze enjoyed genuine popularity. Unlike Molotov or Kaganovich, he was reputed on occasion to stand up to Stalin and to try to soften his cruel disposition. It is quite possible that the very fact of their early intimacy, the memory of the pre-Revolution days when Ordzhonikidze ranked him in the Party, now grated on Stalin. Later on it was alleged that the tyrant's new favorite, then head of the Transcaucasian Party, Lavrenti Beria, had for a long time intrigued against Ordzhonikidze and worked systematically to arouse Stalin's suspicions against him. Beria's rise was enhanced by the very fact that those who knew him, like Ordzhonikidze, considered him a scoundrel and advised Stalin accordingly: a man like that had to be personally loyal; perhaps the very hostility against him was prompted by fear that he would unmask their intrigues, tell Stalin what they were saying behind his back."

The first of what became known as show trials took place in August 1936, when Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin appeared in court. Soon after their execution, Yuri Piatakov, who was Sergo Ordzhonikidze's deputy, was arrested. Ordzhonikidze is said to have tried to intercede with Stalin to secure Piatakov's freedom, but Nikolai Yezhov, the head of the NKVD, was able to show him details of a confession where he admitted being involved in a plot with Leon Trotsky to "overthrow the Bolshevik regime." According to Nickolai Bukharin, who was present, Ordzhonikidze was invited to a "confrontation" with the arrested Piatakov, where he asked his deputy whether his confessions were coerced or voluntary. Piatakov answered that they were completely voluntary.

In December 1936 Lavrenty Beria arrested Papulia Ordzhonikidze, Sergo's elder brother, a railway official. His other brother, Valiko, was sacked from his job in the Tiflis Soviet for claiming that Papulia was innocent. Ordzhonikidze's home was searched by the NKVD. Ordzhonikidze complained to Anastas Mikoyan: "I don't understand why Stalin doesn't trust me... I'm completely loyal to him, don't want to fight with him. Beria's schemes play a large part in this - he gives Stalin the wrong information but Stalin trusts him." Ordzhonikidze added that he could not understand how "he could put honest men in prison and then shoot them for sabotage".

Death of Sergo Ordzhonikidze

On 17th February the NKVD searched Ordzhonikidze's offices. He complained to Stalin but he replied that it was just a routine investigation. The following morning Ordzhonikidze committed suicide by shooting himself in the chest. Within an hour Joseph Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrei Zhdanov, Kliment Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich, Lavrenty Beria and Nikolai Yezhov arrived at the apartment. However, Beria soon left after he was physically attacked by Ordzhonikidze wife, Zinaida.

Stalin insisted that the press be told that Ordzhonikidze had died of a heart attack. Zinaida protested that "No one will believe that. Sergo loved the truth. The truth must be printed." Stalin was insistent and on the 19th February, 1937, the newspapers announced the death of Sergo by heart attack. Four doctors signed the bulletin: "At 17.30, while he was having his afternoon rest, he suddenly felt ill and a few minutes later died of paralysis of the heart." Within a few weeks three of the four doctors were dead, including Grigory Kaminsky, the Commissar for Health, who was executed.

Primary Sources

(1) Adam B. Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007)

He was shadowed by the police as he was leaving Baku. On April 7 he was in Moscow, conferring with Ordzhonikidze and Malinovsky. But the two Georgians obviously could not be arrested in Moscow, for this would have thrown suspicion on Malinovsky, so they were allowed to leave for St. Petersburg on April 9 in the discreet company of three police agents. In the next few weeks the Bolsheviks' entire Russian Bureau was "busted." Ordzhonikidze was arrested on April 14, Stalin on April 22, then Spandaryan and Yelena Stasova, the Central Committee's new agent for the Caucasus.

(2) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003)

Shortly before Nestor Lakoba's sinister death (28th December, 1936), Beria arrested Papulia Ordzhonikidze, Sergo's elder brother, a railway official. Beria knew that his former patron, Sergo, had warned Stalin that he was a "scoundrel". Sergo refused to shake hands with Beria and built a special fence between their dachas.Beria's vengeance was just one of the ways in which Stalin began to turn the heat on to the emotional Sergo, the industrial magnifico who supported the regime's draconian policies but resisted the arrest of his own managers. The star of the next show trial was to be Sergo's Deputy Commissar, Yury Pyatakov, an ex-Trotskyite and skilled manager. The two men were fond of one another and enjoyed working together.

In July, Pyatakov's wife had been arrested for her links to Trotsky. Shortly before the Zinoviev trial, Yezhov summoned Pyatakov, read him all the affidavits implicating him in Trotskyite terrorism and informed him that he was relieved of his job as Deputy Commissar. Pyatakov offered to prove his innocence by asking to be "personally allowed to shoot all those sentenced to death at the trial, including his former wife and to publish this in the press". As a Bolshevik, he was willing even to execute his own wife.

"I pointed out to him the absurdity of his proposal," Yezhov reported drily to Stalin. On 12 September, Pyatakov was arrested. Sergo, recuperating in Kislovodsk, voted for his expulsion from the Central Committee but he must have been deeply worried. A shadow of his former self, grey and exhausted, he was so ill that the Politburo restricted him to a three-day week. Now the NKVD began to arrest his specialist non-Bolshevik advisers and he appealed to Blackberry: "Comrade Yezhov, please look into this." He was not alone. Kaganovich and Sergo, those "best friends", not only shared the same swaggering dynamism but both headed giant industrial commissariats. Kaganovich's railway experts were being arrested too. Meanwhile Stalin sent Sergo transcripts of Pyatakov's interrogations in which his deputy confessed to being a "saboteur". The destruction of "experts" was a perennial Bolshevik sport but the arrest of Sergo's brother revealed Stalin's hand: "This couldn't have been done without Stalin's consent. But Stalin's agreed to it without even calling me," Sergo told Mikoyan. "We were such close friends! And suddenly he lets them do such a thing!" He blamed Beria.

Sergo appealed to Stalin, doing all he could to save his brother. He did too much: the arrest of a man's clan was a test of loyalty. Stalin was not alone in taking a dim view of this bourgeois emotionalism: Molotov himself attacked Sergo for being "guided only by emotions... thinking only of himself."

On 9 November, Sergo suffered another heart attack. Meanwhile, the third Ordzhonikidze brother, Valiko, was sacked from his job in the Tiflis Soviet for claiming that Papulia was innocent. Sergo swallowed his pride and called Beria, who replied:

"Dear Comrade Sergo! After your call, I quickly summoned Valiko ... Today Valiko was restored to his job. Yours L. Beria." This bears the pawprints of Stalin's cat-and-mouse game, his meandering path to open destruction, perhaps his moments of nostalgic fondness, his supersensitive testing of limits. But Stalin now regarded Sergo as an enemy: his biography had just been published for his fiftieth birthday and Stalin studied it carefully, scribbling sarcastically next to the passages that acclaimed Sergo's heroism:

"What about the CC? The Party?" Stalin and Sergo returned separately to Moscow where fifty-six of the latter's officials were in the toils of the NKVD. Sergo however remained a living restraint on Stalin, making brave little gestures towards the beleaguered Rightists. "My dear kind warmly blessed Sergo," encouraged Bukharin: "Stand firm!" At the theatre, when Stalin and the Politburo filed into the front seats, Sergo spotted ex-Premier Rykov and his daughter Natalya (who tells the story), alone and ignored, twenty rows up the auditorium. Leaving Stalin, Sergo galloped up to kiss them. The Rykovs were moved to tears in gratitude.

(3) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004)

In lighting the match, Stalin did not necessarily have a predetermined plan any more than he had had one for economic transformation at the beginning of 1928. Although the victim-categories overlapped each other, there was no inevitability in his deciding to move against all of them in this small space of time. But the tinderbox had been sitting around in an exposed position. It was there to be ignited and Stalin, attending to all the categories one after another, applied the flame.

Trotsky's former ally Georgi Pyatakov had been arrested before Yezhov's promotion. Pyatakov had been working efficiently as Ordzhonikidze's deputy in the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry. Ordzhonikidze, in discussions after the December 1936 Central Committee plenum, refused to believe the charges of terrorism and espionage laid against him. This was a battle Stalin had to win if he was to proceed with his campaign of repression. Pyatakov was placed under psychological pressure to confess to treasonous links with counter-revolutionary groups. He cracked. Brought out to an interview with Ordzhonikidze in Stalin's presence, he confirmed his testimony to the NKVD. In late January 1937 a second great show trial was held. Pyatakov, Sokolnikov, Radek and Serebryakov were accused of heading an Anti-Soviet Trotskyist Centre. The discrepancies in evidence were large but the court did not flinch from sentencing Pyatakov and Serebryakov to death while handing out long periods of confinement to Radek and Sokolnikov. Meanwhile Ordzhonikidze's brother had been shot on Stalin's instructions. Ordzhonikidze himself fell apart: he went off to his flat on 18 February 1937 after a searing altercation with Stalin and shot himself. There was no longer anyone in the Politburo willing to stand up to Stalin and halt the machinery of repression.

(4) John Archibald Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (2010)

From the fall of 1936 the NKVD began to arrest economic officials, mostly of low rank, ostensibly in connection with various incidents of industrial sabotage. By the beginning of 1937 nearly a thousand persons working in economic commissariats were under arrest. The real bombshell, however, came in mid-September when Deputy Commissar of Heavy Industry Piatakov was arrested. Piatakov, a well-known former Trotskyist, had been under a cloud at least since July, when an NKVD raid on the apartment of his ex-wife turned up compromising materials on his Trotskyist activities ten years earlier. In August, Yezhov interviewed him and told him that he was being transferred to a position as head of a construction project. Piatakov protested his innocence, claiming that his only sin was in not seeing the counterrevolutionary activities of his wife. He offered to testify against Zinoviev and Kamenev and even volunteered to execute them personally, along with his ex-wife. (Yezhov declined the offer as "absurd.") During August, Piatakov wrote both to Stalin and Ordzhonikidze, protesting his innocence and referring to Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Trotsky as "rotten" and "base. None of this did him any good. He was expelled from the party on 11 September and arrested the next day....

There are no documents attesting to Ordzhonikidze's protest. Aside from the account of his attendance at Piatakov's confrontation, we have only a couple of oblique references by Stalin and Molotov at the next plenum (February-March 1937) that Ordzhonikidze had been slow to recognize the guilt of some enemies. But there is no evidence that his intervention took the form of protest against the use of terror against party enemies; he was by no means a "liberal" in such matters. Ordzhonikidze, as far as we know, never complained about the measures against Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky, or any other oppositionist per se. His defense of "enemies" was a bureaucrat's defense of "his people," with whom he worked and whom he needed to make his organization function. From his point of view, Yezhov's depredations were improper only when they intruded into Ordzhonikidze's bailiwick, when they threatened the smooth fulfillment of the economic plans his organization answered for, and when they infringed on his circle of clients. As a card-carrying member of the upper nomenklatura, Ordzhonikidze was not against using terror against the elite's enemies, but he did fight to protect the patronage rights that he enjoyed as a member of that stratum.

(5) Adam B. Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007)

Symbolically the first major victim following the trial was a man from Stalin's closest circle. Gregory "Sergo" Ordzhonikidze was his oldest friend, a member of the Politburo, Commissar of Heavy Industry. In Party circles Ordzhonikidze enjoyed genuine popularity. Unlike Molotov or Kaganovich, he was reputed on occasion to stand up to Stalin and to try to soften his cruel disposition. It is quite possible that the very fact of their early intimacy, the memory of the pre-Revolution days when Ordzhonikidze ranked him in the Party, now grated on Stalin. Later on it was alleged that the tyrant's new favorite, then head of the Transcaucasian Party, Lavrenti Beria, had for a long time intrigued against Ordzhonikidze and worked systematically to arouse Stalin's suspicions against him. But it is over simple to see Beria as Stalin's evil spirit and a major cause of the Great Purge. Still, with his ever deepening suspicions and a growing apprehension of what might happen when war came, Stalin was not unwilling to listen to tales about people closest to him and came to resent those who had known him as Koba. Beria's rise was enhanced by the very fact that those who knew him, like Ordzhonikidze, considered him a scoundrel and advised Stalin accordingly: a man like that had to be personally loyal; perhaps the very hostility against him was prompted by fear that he would unmask their intrigues, tell Stalin what they were saying behind his back. In his new phase Stalin subjected some of his leading collaborators (Kaganovich, Kalinin, Molotov, Mikoyan) to an inhuman test: close relatives would be arrested and held on fictitious charges while they were supposed to go on serving him without interceding for their dear ones. Now Ordzhonikidze, to the public one of the first men in the state and a "close comrade-at-arms of great Stalin," was expected to be working at his desk, appear smiling in photographs at the side of the Leader, while somewhere in an NKVD jail his older brother Papulia was being tortured. Ordzhonikidze was not a healthy man: he had undergone operations and suffered from high blood pressure and a heart ailment. And now on February 19 the Central Committee was to assemble to consider the "lessons" of the Pyatakov-Radek trial and to order new measures of repression against wreckers and saboteurs. Ordzhonikidze's part was a key one: his deputy Pyatakov had been shot, several of his most important subordinates and industrial directors had been arrested. He was to make a report on "wrecking" in industry and on further measures of repression to deal with spies and saboteurs.

But the meeting had to be adjourned. On the very day it was slated to open, newspapers carried the news of Ordzhonikidze's sudden death on the preceding day from a heart attack.

That Ordzhonikidze in fact committed suicide was well known in top Party circles, and it is incredible - as Khrushchev, in 1937 head of the Moscow Party organization, was to allege in 1956 - that Khrushchev learned the true facts of the death only many years later. We know that on the morning of February 17 Ordzhonikidze had a tempestuous interview with Stalin. He wanted to know why his office had been searched by the NKVD. Nothing unusual about it, replied Stalin; why, the NKVD might very well be ordered to search his own office Ordzhonikidze worked for the balance of the day in his Commissariat, attending to various items of business, issuing dispositions for the future. He returned to his Kremlin apartment at two A.M. The next morning he refused to get out of bed, and at five-thirty in the afternoon the shot rang out. Zinaida Gavrilovna Ordzhonikidze phoned Stalin, but he refused to see the widow of his lifelong friend alone, and arrived only after a while, accompanied by other members of the Politburo and Yezhov. According to Roy Medvedev, who collected evidence from eyewitnesses, Zinaida Gavrilovna shouted at the dictator, "You did not protect Sergo for me or for the Party" - certainly in the circumstances a masterpiece of understatement. Stalin's unsentimental reply was, "Shut up, you fool." His reaction on the death of the man whose recommendation had been instrumental in Lenin's appointing him to the Central Committee in 1912, and whose help had been essential at several other crucial points of his career, was one of wonder: "What an odd disease. Man lies down to rest, has a heart attack, and there." This, it is hardly necessary to add, was the official verdict of the medical certificate signed by four distinguished doctors, three of whom were subsequently liquidated.

"Why did Ordzhonikidze shoot himself and not Stalin?" asks a Soviet author. We have already tried to answer this question. Knowing him well, it is unlikely that Ordzhonikidze could have thought that his act of desperation would bring any remorse in Stalin or make him abandon or temper his bloody designs. The tyrant must have viewed his friend's suicide as an attack upon himself, a stab in the back: Ordzhonikidze deserted his post, tried to bring confusion and doubt into the highest Party ranks, discredit that essential work being done by the NKVD. It was undoubtedly great generosity on his part, Stalin believed, to cover his dead comrade with honors, to give him a hero's funeral, and to leave that chatterbox, Ordzhonikidze's wife, free. But Stalin's suspicions pursued a person even after his death. As after his wife's death, Stalin now brooded over the meaning of Sergo's suicide: What had he really meant by this act? Would his relatives talk, spread the true story, breed defeatism through gossip? One by one Ordzhonikidze's closest relatives and co-workers who knew the facts were arrested. In 1942, the year of supreme danger, when the Germans approached the Caucasus, Stalin remembered his fellow Caucasian, and orders went out to change the names of several cities and towns called after Ordzhonikidze There was no point in commemorating the man who had betrayed him.

(6) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003)

Stalin carefully prepared for the Plenum that would formally open the Terror against the Party itself. On 31 January, the Politburo appointed the two industrial kingpins to speak about wrecking in their departments. Stalin reviewed their speeches. Sergo accepted that wreckers had to be stopped but wanted to say that now they had been arrested, it was time to return to normality. Stalin angrily scribbled on Sergo's speech: "State with facts which branches are affected by sabotage and exactly how they are affected." When they met, Sergo seemed to agree but he quietly dispatched trusted managers to the regions to investigate whether the NKVD was fabricating the cases: a direct challenge to Stalin.An ailing Sergo realized that the gap between them was widening. He faced a rupture with the Party to which he had devoted his life....

"Stalin's started a bad business," said Sergo. `I was always such a close friend of Stalin's. I trusted him and he trusted me. And now I can't work with him, I'll commit suicide." Mikoyan told him suicide never solved anything but there were now frequent suicides. On 17 February, Sergo and Stalin argued for several hours. Sergo then went to his office before returning at 3 p.m. for a Politburo meeting.

Stalin approved Yezhov's report but criticized Sergo and Kaganovich who retired to Poskrebyshev's study, like schoolboys to rewrite their essays. At seven, they too walked, talking, around the Kremlin: 'he was ill, his nerves broken," said Kaganovich.

Stalin deliberately turned the screw: the NKVD searched Sergo's apartment. Only Stalin could have ordered such an outrage. Besides, the Ordzhonikidzes spent weekends with the Yezhovs, but friendship was dust compared to the orders of the Party. Sergo, as angry and humiliated as intended, telephoned Stalin:

"Sergo, why are you upset?" said Stalin. "This Organ can search my place at any moment too." Stalin summoned Sergo who rushed out so fast, he forgot his coat. His wife Zina hurried after him with the coat and fur hat but he was already in Stalin's apartment. Zina waited outside for an hour and a half. Stalin's provocations only confirmed Sergo's impotence, for he "sprang out of Stalin's place in a very agitated state, did not put on his coat or hat, and ran home". He started retyping his speech, then, according to his wife, rushed back to Stalin who taunted him more with his sneering marginalia: "Ha-ha!"

Sergo told Zina that he could not cope with Koba whom he loved. The next morning, he remained in bed, refusing breakfast. "I feel bad," he said. He simply asked that no one should disturb him and worked in his room. At 5.30 p.m. Zinaida heard a dull sound and rushed into the bedroom.

Sergo lay bare-chested and dead on the bed. He had shot himself in the heart, his chest powder-burned. Zina kissed his hands, chest, lips fervently and called the doctor who certified he was dead. She then telephoned Stalin who was at Kuntsevo. The guards said he was taking a walk but she shouted:

"Tell Stalin it's Zina. Tell him to come to the phone right away. I'll wait on the line."

"Why the big hurry?" Stalin asked. Zina ordered him to come urgently:

"Sergo's done the same as Nadya!" Stalin banged down the phone at this grievous insult.

It happened that Konstantin Ordzhonikidze, one of Sergo's brothers, arrived at the apartment at this moment. At the entrance, Sergo's chauffeur told him to hurry. When he reached the front door, one of Sergo's officials said simply:

"Our Sergo's no more." Within half an hour, Stalin, Molotov and Zhdanov (for some reason wearing a black bandage on his forehead) arrived from the countryside to join Voroshilov, Kaganovich and Yezhov. When Mikoyan heard, he exclaimed, "I don't believe it" and rushed over. Again the Kremlin family mourned its own but suicide left as much anger as grief.Zinaida sat on the edge of the bed beside Sergo's body. The leaders entered the room, looked at the corpse and sat down. Voroshilov, so soft-hearted in personal matters, consoled Zina:

"Why console me," she snapped, "when you couldn't save him for the Party?" Stalin caught Zina's eye and nodded at her to follow him into the study. They stood facing each other. Stalin seemed crushed and pitiful, betrayed again.

"What shall we say to people now?" she asked.

"This must be reported in the press," Stalin replied. "We'll say he died of a heart attack."

"No one will believe that," snapped the widow. "Sergo loved the truth. The truth must be printed."

"Why won't they believe it? Everyone knew he had a bad heart and everyone will believe it," concluded Stalin. The door to the death-room was closed but Konstantin Ordzhonikidze peeped inside and observed Kaganovich and Yezhov in consultation, sitting at the foot of the body of their mutual friend. Suddenly Beria, in Moscow for the Plenum, appeared in the dining room. Zinaida charged at him, trying to slap him, and shrieked: "Rat!" Beria "disappeared right afterwards".

They carried Sergo's bulky body from the bedroom and laid him on the table. Molotov's brother, a photographer, arrived with his camera. Stalin and the magnates posed with the body.

(7) Sergo Ordzhonikidze's youngest brother Konstantin arrived at the Kremlin soon after his body had been found.

When my wife and I reached the second floor, we went to the dining room, but were stopped at the door by the NKVD agent. Then we were let into Sergo's office, where I saw Gvakhariia. "Our Sergo is no more," he said. I ran to the bedroom but my way was barred, and I was not allowed to see the body.

Then Stalin, Molotov, and Zhdanov arrived. Sergo's secretary, Makhover, uttered words that stick in my memory: "They killed him, the rats".