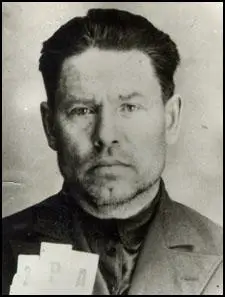

Martemyan Ryutin

Martemyan Ryutin was born into a poor peasant family in Irkutsk in Siberia in 1890. He developed left-wing political views and in 1914 he joined the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP).

Ryutin took part in the Russian Revolution and in 1917 he became head of a local soviet in Harbin. During the Russian Civil War commanded a unit of the Red Army. In 1920 he joined the executive committee of the local section of the Communist Party. In 1924 he was sent to Moscow where he headed several important party committees. In December 1925 he was a delegate to the 14th Congress of the Communist Party.

In 1925 Joseph Stalin switched his support from Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev to Bukharin and now began advocating the economic policies of Nickolai Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov. The historian, Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has pointed out: "Tactical reasons compelled him to join hands with the spokesmen of the right, on whose vote in the Politburo he was dependent. He also felt a closer affinity with the men of the new right than with his former partners. Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky accepted his socialism in one country, while Zinoviev and Kamenev denounced it. Bukharin may justly be regarded as the co-author of the doctrine. He supplied the theoretical arguments for it and he gave it that scholarly polish which it lacked in Stalin's more or less crude version."

Stalin wanted an expansion of the New Economic Policy that had been introduced several years earlier. Farmers were allowed to sell food on the open market and were allowed to employ people to work for them. Those farmers who expanded the size of their farms became known as kulaks. Bukharin believed the NEP offered a framework for the country's more peaceful and evolutionary "transition to socialism". He disregarded traditional party hostility to kulaks and called on them to "enrich themselves".

Ryutin was closely associated with the policies of Bukharin. In the spring of 1928, Joseph Stalin began dismissing local officials who were known to supporters of Bukharin. At the same time, Stalin made speeches attacking the kulaks for not supplying enough food for the industrial workers. Bukharin was furious and sought help from Alexei Rykov and Maihail Tomsky, in an effort to combat Stalin. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out: "In spring 1928 Bukharin mobilized his supporters, Rykov, then head of government, and the Trades Union leader Tomsky, and they all wrote notes to the Politburo about the threat to the alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry, naturally invoking Lenin. Stalin did not intend to annihilate Bukharin just yet. He was making a 180-degree turn, and needed Bukharin to explain it from the standpoint of Marxism."

In November, 1929, Nickolai Bukharin, was removed from the Politburo. Stalin now decided to declare war on the kulaks. The following month he made a speech where he argued: "Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes… Now dekulakisation is being undertaken by the masses of the poor and middling peasant masses themselves, who are realising total collectivisation. Now dekulakisation in the areas of total collectivisation is not just a simple administrative measure. Now dekulakisation is an integral part of the creation and development of collective farms. When the head is cut off, no one wastes tears on the hair."

Ryutin was sent to investigate the progress of collectvization in the grain-producing areas of Siberia. When he arrived back in Moscow he criticised the program in a report to the Politburo. In January 1930, Ryutin published an article in Red Star which challenged the wisdom of this agricultural policy. Unlike people like Bukharin, he refused to endorse the policies of Joseph Stalin. As a result he was expelled from the Supreme Council of National Economy.

In the summer of 1932 Ryutin wrote a 200 page analysis of Stalin's policies and dictatorial tactics, Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship. Ryutin argues: "The party and the dictatorship of the proletariat have been led into an unknown blind alley by Stalin and his retinue and are now living through a mortally dangerous crisis. With the help of deception and slander, with the help of unbelievable pressures and terror, Stalin in the last five years has sifted out and removed from the leadership all the best, genuinely Bolshevik party cadres, has established in the VKP(b) and in the whole country his personal dictatorship, has broken with Leninism, has embarked on a path of the most ungovernable adventurism and wild personal arbitrariness."

Ryutin then went onto making a very personal attack on Stalin: "To place the name of Stalin alongside the names of Marx, Engels and Lenin means to mock at Marx, Engels and Lenin. It means to mock at the proletariat. It means to lose all shame, to overstep all hounds of baseness. To place the name of Lenin alongside the name of Stalin is like placing Mt. Elbrus alongside a heap of dung. To place the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin alongside the works of Stalin is like placing the music of such great composers as Beethoven, Mozart, Wagner and others alongside the music of a street organgrinder... Lenin was a leader but not a dictator. Stalin, on the contrary, is a dictator but not a leader."

Ryutin did not only blame Stalin for the problems facing the Soviet Union: "The entire top leadership of the Party leadership, beginning with Stalin and ending with the secretaries of the provincial committees are, on the whole, fully aware that they are breaking with Leninism, that they are perpetrating violence against both the Party and non-Party masses, that they are killing the cause of socialism. However, they have become so tangled up, have brought about such a situation, have reached such a dead-end, such a vicious circle, that they themselves are incapable of breaking out of it... The mistakes of Stalin and his clique have turned into crimes.... In the struggle to destroy Stalin's dictatorship, we must in the main rely not on the old leaders but on new forces. These forces exist, these forces will quickly grow. New leaders will inevitably arise, new organizers of the masses, new authorities. A struggle gives birth to leaders and heroes. We must begin to take action."

John Archibald Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, the authors of The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (2010) have argued: "This manifesto of the Union of Marxist-Leninists was a multifaceted, direct, and trenchant critique of virtually all of Stalin's policies, his methods of rule, and his personality. The Ryutin Platform, drafted in March, was discussed and rewritten over the next few months. At an underground meeting of Ryutin's group in a village in the Moscow suburbs on 21 August 1932, the document was finalized by an editorial committee of the Union.... At a subsequent meeting, the leaders decided to circulate the platform secretly from hand to hand and by mail. Numerous copies were made and circulated in Moscow, Kharkov, and other cities. It is not clear how widely the Ryutin Platform was spread, nor do we know how many party members actually read it or even heard of it. The evidence we do have, however, suggests that the Stalin regime reacted to it in fear and panic."

An unknown member of the Union of Marxist-Leninists turned it over to Military Intelligence (GRU). General Yan Berzin obtained a copy and called a meeting of his most trusted staff to discuss and denounce the work. Walter Krivitsky remembers Berzen reading excerpts of the manifesto in which Ryutin called "the great agent provocateur, the destroyer of the Party" and "the gravedigger of the revolution and of Russia."

Stalin interpreted Ryutin's manifesto as a call for his assassination. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Stalin also attacked those who were calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. The Leningrad Party chief, Sergy Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Stalin's close friend, also agreed with Kirov. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin.

On 22nd September, 1932, Ryutin was arrested and held for investigation. During the investigation Ryutin admitted that he had been opposed to Stalin's policies since 1928. On 27th September, Ryutin and his supporters were expelled from the Communist Party. Ryutin was also found guilty of being an "enemy of the people" and was sentenced to a 10 years in prison. Soon afterwards Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were expelled from the party for failing to report the existence of Ryutin's report.

Martemyan Ryutin was executed on 10th January, 1937. His two sons, Vassily (born 1910) and Vissarion (born 1913), were both executed. Ryutin's wife was sent to the Gulag in Karaganda, where she later died.

Primary Sources

(1) John Archibald Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (2010)

M. N. Riutin had been a district party secretary in the Moscow party organization in the 1920s and had supported Bukharin's challenge to Stalin's policy of collectivization. But unlike Bukharin and the other senior rightist leaders, he had refused to recant and to formally support Stalin's course. As a result, he had been stripped of his party offices and expelled from the party in 1930 "for propagandizing right-opportunist views." Riutin remained in contact with fellow opponents inside the party, and in March of 1932 - a secret meeting of his group produced two documents. One of these was a seven-page typewritten appeal "To All Members of the VKP(b)," which gave an abbreviated critique of Stalin and his policies and called on all party members to oppose them in any ways they could. At the bottom of the appeal from the "All Union Conference `Union of Marxist-Leninists"' was the request to read the document, copy it, and pass it along to others.

By far the most important document drafted at the March 1932 meeting was the so-called Riutin Platform, formally entitled "Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship." This manifesto of the Union of Marxist-Leninists was a multifaceted, direct, and trenchant critique of virtually all of Stalin's policies, his methods of rule, and his personality. The Riutin Platform, drafted in March, was discussed and rewritten over the next few months. At an underground meeting of Riutin's group in a village in the Moscow suburbs on 21 August 1932, the document was finalized by an editorial committee of the Union. (Riutin, at his own request, was not formally a member of the committee because at that time he was not a party member.) At a subsequent meeting, the leaders decided to circulate the platform secretly from hand to hand and by mail. Numerous copies were made and circulated in Moscow, Kharkov, and other cities.

It is not clear how widely the Riutin Platform was spread, nor do we know how many party members actually read it or even heard of it. The evidence we do have, however, suggests that the Stalin regime reacted to it in fear and panic. The document's call to "destroy Stalin's dictatorship" was taken as a call for armed revolt.

One of the contacts receiving the platform turned it over to the secret police. Arrests of Union members began as early as September 1932. The entire editorial board, plus Riutin, was arrested in the fall of 1932; all were expelled from the party and sentenced to prison for membership in a "counterrevolutionary organization." Riutin himself was sentenced to ten years in prison. There is a persistent myth that Stalin unsuccessfully demanded the death penalty for those connected with the Riutin Platform but was blocked by a majority of the Politburo. At any rate, by early

1937 all the central figures in the Riutin opposition group had been shot for treason.At the end of 1932 many of the former leaders of opposition movements, including G. E. Zinoviev, L. B. Kamenev, Karl Radek, and others, were summoned to party disciplinary bodies and interrogated about their possible connection to the group; some were expelled anew from the party simply for knowing of the existence of the Riutin Platform, whether they had read it or not. Indeed, in coming years having read the platform, or even knowing about it and not reporting that knowledge to the party, would be considered a crime. In virtually all inquisitions of former oppositionists from 1934 to 1939, this "terrorist document" would be used as evidence connecting Stalin's opponents to various treasonable conspiracies. By providing a cohesive alternative discourse around which rank-and-file party members might unite against the elite, the platform threatened nomenklatura control...

To those who defended the monopoly version of political reality, this text inspired fear and anger. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Riutin Platform began the process that would lead to terror, precisely by terrifying the ruling nomenklatura. Why did this document provoke such fury in the highest levels of the party leadership? First of all, it was a text, and to those who took such pains to produce political documents, the appearance of an actual alternative written text carried special significance. So anxious was the regime to bury the Riutin Platform that it has proved impossible to find an original copy in any Russian archive. (The surviving text is taken from a typescript copy made by the secret police in 1932.) Indeed, it seems that the words themselves were considered dangerous.

Reaction to them recalls Foucault's description of the speech of a "medieval madman" whose utterances were beyond the limits of accepted speech but at the same time had a power, a prescience, and a kind of magic revealing a hidden and dangerous truth. Similarly, Trotsky's writings in exile were sharply proscribed but were carefully read by Stalinist leaders in the 1930s. To the Stalinists, the words of Riutin and Trotsky seem to have had a special kind of threatening quality, and the reaction of the elite to them seems to reflect a fear of the language itself.

Second, the Riutin Platform subjected the Stalin leadership to a sustained and withering criticism for its agricultural, industrial, and inner-party policies that remained the most damning indictment of Stalinism from inside the Soviet Union until the Gorbachev period. Even Nikita Khrushchev's 19 56 "Secret Speech" was neither as comprehensive nor as negative in its assessment of Stalin. The language was bitter, combative, and insulting to anyone in the party leadership.

Third, the Riutin Platform could not have come at a more dangerous time for the party leadership. The industrialization drive of the first Five Year Plan had not brought economic stability, and although growth was impressive, so were the chaos and upheaval caused by mass urbanization, clogged transport, and falling real wages. The situation in the countryside was even more threatening. Collectivization and peasant resistance to it had led to the famine of 1932; eventually millions of "unnatural deaths" from starvation and repression would be recorded. Faced with this disaster, the Stalinist leadership held its cruel course and refused to abandon its forced collectivization of agriculture. On lower levels of the party, however, many in the field charged with implementation began to waver. Reluctant to consign local populations to mass death, many local party officials refused to push relentlessly forward and actually argued with the center about the high grain collection targets. The country and its ruling apparatus were falling apart. In such conditions, any dissident group emerging from within the besieged party was bound to provoke fear, panic, and anger from a leadership that worshiped party unity and discipline.

Finally, and politically most important, the platform threatened to carry the party leadership struggle outside the bounds of the ruling elite, the nomenklatura. The leftist opposition of the mid-1920s had attempted to do this as well by organizing public demonstrations and by agitating the rank and file of the party. The response of the leadership at that time - which included not only the Stalinists but also the moderate Bukharinists and indeed the vast majority of the party elite-had been swift and severe: expulsion from the party and even arrest. Although leaders might fight among themselves behind closed doors, any attempt to carry the struggle to the party rank and file or to the public could not be tolerated. Such a struggle not only would open the door to a split in the party between left and right but would raise the possibility of an even more dangerous rift between top and bottom within the party. Such a danger was particularly acute in 1932, with the reluctance of some local party members to press collectivization as hard as Moscow demanded. Such a split would almost certainly destroy the Leninist generation, which saw itself as the bearers of communist ideology and as the vanguard of the less politically conscious working class and the mass of untutored new party members inducted since the Civil War. But the idea of Leninism was not the only thing at stake. Isolated as they were in the midst of a sullen peasant majority-relatively few communists in a sea of peasants who wanted nothing more than private property-the Bolsheviks realized that only military discipline and party unity could keep them in power, especially during a crisis in which their survival was threatened. The nomenklatura was therefore personally threatened by opposition movements that sought to set the rank and file against the leadership. Back in the 1930s the Trotskyist opposition had taken the argument outside the party leadership and literally to the streets; Trotskyists had organized a public demonstration against the party leadership. After this dangerous experience, the elite at all levels understood the dangers posed by a politicization of the masses on terms other than those prescribed by the elite.

It was this understanding of group solidarity that had prevented the rightist (Bukharinist) opposition from lobbying outside the ruling stratum. The risks were too high, especially in an unstable social and political situation where the party did not command the loyalty of a majority of the country's population. Accordingly, the sanctions taken against the defeated rightists were much lighter than those earlier inflicted on the Trotskyists. Although some of the rightists were expelled from the party, and its leaders lost their highest positions, Bukharin and his fellow leaders remained members of the Central Committee. They had, after all, played according to the terms of the unwritten gentleman's agreement not to carry the struggle outside the nomenklatura.

Although the Riutin Platform is notable for its assault on Stalin personally, it was also attacking the ruling group in the party and the stratified nomenklatura establishment that had taken shape since the 1920s. That elite regarded the platform as a call for revolution from within the party. After the Riutin incident, the ruling stratum reacted more and more sharply to any criticism of Stalin, not because they feared him - although events would show that they should have - but because they needed him to stay in power. In this sense, Stalin's interests and those of the nomenklatura coincided.

Although the Riutin Platform originated in the right wing of the Bolshevik party, its specific criticisms of the Stalinist regime were in the early 1930s shared by the more leftist Lev Trotsky, who also had sought to organize political opposition "from below." Trotsky had been expelled from the Bolshevik Party in 1927 and exiled from the Soviet Union in 1927. Since that time, he had lived in several exile locations, writing prolifically for his Bulletin of the Opposition. Like the Riutin group, Trotsky believed that the Soviet Union in 1932 was in a period of extreme crisis provoked by Stalin's policies. Like them, he believed that the rapid pace of forced collectivization was a disaster and that the hurried and voluntarist nature of industrial policy made rational planning impossible, resulting in a disastrous series of economic "imbalances." Along with the Riutinists, Trotsky called for a drastic change in economic course and democratization of the dictatorial regime within a party that suppressed all dissent. According to Trotsky, Stalin had brought the country to ruin.

At the same time the Riutin group was forging its programmatic documents, Trotsky was attempting to activate his followers in the Soviet Union. Most of the leaders of the Trotskyist opposition had capitulated to Stalin in 1929-31, as Stalin's sharp leftist change of course seemed to them consistent with the main elements of the Trotsky critique in the 1920s. Trotsky himself, however, along with a small group of "irreconcilables," had refused to accept Stalin's leftist change of course and remained in opposition.

(2) Martemyan Ryutin, Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship (1932)

The party and the dictatorship of the proletariat have been led into an unknown blind alley by Stalin and his retinue and are now living through a mortally dangerous crisis. With the help of deception and slander, with the help of unbelievable pressures and terror, Stalin in the last five years has sifted out and removed from the leadership all the best, genuinely Bolshevik party cadres, has established in the VKP(b) and in the whole country his personal dictatorship, has broken with Leninism, has embarked on a path of the most ungovernable adventurism and wild personal arbitrariness....

To place the name of Stalin alongside the names of Marx, Engels and Lenin means to mock at Marx, Engels and Lenin. It means to mock at the proletariat. It means to lose all shame, to overstep all hounds of baseness. To place the name of Lenin alongside the name of Stalin is like placing Mt. Elbrus alongside a heap of dung. To place the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin alongside the works of Stalin is like placing the music of such great composers as Beethoven, Mozart, Wagner and others alongside the music of a street organgrinder....

Lenin was a leader but not a dictator. Stalin, on the contrary, is a dictator but not a leader....

The entire top leadership of the Party leadership, beginning with Stalin and ending with the secretaries of the provincial committees are, on the whole, fully aware that they are breaking with Leninism, that they are perpetrating violence against both the Party and non-Party masses, that they are killing the cause of socialism. However, they have become so tangled up, have brought about such a situation, have reached such a dead-end, such a vicious circle, that they themselves are incapable of breaking out of it.

The mistakes of Stalin and his clique have turned into crimes....

In the struggle to destroy Stalin's dictatorship, we must in the main rely not on the old leaders but on new forces. These forces exist, these forces will quickly grow. New leaders will inevitably arise, new organizers of the masses, new authorities.

A struggle gives birth to leaders and heroes. We must begin to take action...

(3) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004)

The firmness shown by Stalin in 1930-1 failed to discourage confidential criticism in the upper echelons of the party. Although the Syrtsov-Lominadze group had been broken up, other little groupings sprouted up. One consisted of Nikolai Eismont, Vladimir Tolmachev and A. P. Smirnov. Denounced by informers in November 1932 and interrogated by the OGPU, they confessed to verbal disloyalty. But this was not enough for Stalin. The joint plenum of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission in January 1933 condemned the leaders for having formed an "anti-party grouping" and took the opportunity to reprimand Rykov and Tomski for maintaining contact with "anti-party elements". Yet no sooner had one grouping been dealt with than another was discovered. Martemyan Ryutin, a Moscow district party functionary, hated Stalin's personal dictatorship. He and several like-minded friends gathered in their homes for evening discussions and Ryutin produced a pamphlet demanding Stalin's removal from office. Ryutin was arrested. Stalin, interpreting the pamphlet as a call for an assassination attempt, urged Ryutin's execution. In the end he was sentenced to ten years in the Gulag.

(4) Adam B. Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007)

Ryutins' had circulated a lengthy memorandum urging the removal of the General Secretary. The Central Control Commission and the GPU dealt with Ryutin and his fellow miscreants in a dilatory and over lenient fashion, Stalin was to feel subsequently. They were expelled from the Party and given prison terms. But the Politburo did not take to hints, and it balked at the "highest measure of punishment" against former Party officials. Were his closest associates hedging their bets? A plot had been hatched against the commander-in-chief of an army engaged in a war, and yet the plotters were let off with prison sentences. Did the CPU really work hard to unravel "the rich threads of treason"? It seemed unlikely that somebody as insignificant as Ryutin would have instigated a plot like that on his own. Stalin, still a master of the art of timing, did not insist on this viewpoint, but neither would he forget. For the moment he was content with pruning the Party rolls: in one year they were reduced from about 3.5 million members and candidates in January 1933 to 2.7 million in December. Such a purge of the rank and file always had a bracing effect. Those retained would be grateful and less inclined to listen to troublemakers; those excluded would be eager to earn their way back by hard work and exemplary loyalty - say, by unmasking some real enemies. A real job of cleansing the Party and especially its hierarchy had to wait until he concluded his campaign against the peasant.