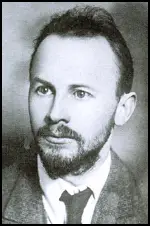

Nikolay Bukharin

Nikolay Bukharin, the second son of Ivan Gavrilovich and Liubov Ivanovna Bukharin, was born in Moscow on 27th September 1888. His parents were primary school teachers and they helped him get a good education. He was brought up with progressive political views and took part in the 1905 Revolution.

In 1906 he joined the Bolsheviks. By 1908 he was a member of the Moscow Party Committee. The following year he was arrested while at a committee meeting. He was released but re-arrested several times and in 1910 decided to go into exile. He lived in Austria, Switzerland, Sweden and the USA. He met all the leading revolutionaries in exile including Lenin, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, and Leon Trotsky. Trotsky met him in New York City and later commented that "he welcomed us with the childish exuberance characteristic of him." During this period Bukharin also wrote for Pravda, Die Neue Zeit and Novy Mir.

After the overthrow of Nicholas II, the new prime minister, Prince Georgi Lvov, allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Joseph Stalin arrived at Nicholas Station in St. Petersburg with Lev Kamenev on 25th March, 1917. His biographer, Robert Service, has commented: "He was pinched-looking after the long train trip and had visibly aged over the four years in exile. Having gone away a young revolutionary, he was coming back a middle-aged political veteran." Bukharin also returned to Russia where he joined the Moscow Soviet and began editing the journal, Spartak.

On 3rd April, 1917, Lenin announced what became known as the April Theses. Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories. Leon Trotsky gave Lenin his full support: "I told Lenin that nothing separated me from his April Theses and from the whole course that the party had taken since his arrival."

Lev Kamenev led the opposition to Lenin's call for the overthrow of the government. In Pravda he disputed Lenin's assumption that the bourgeois democratic revolution has ended," and warned against utopianism that would transform the "party of the revolutionary masses of the proletariat" into "a group of communist propagandists." A meeting of the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee the day after the April Theses appeared voted 13 to 2 to reject Lenin's position.

Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) has argued that Lenin now set about changing the minds of the Bolsheviks. "He was distinctly a father-figure: at forty-eight, he was ten years or more the senior of the other Bolshevik leaders. And he had a few key helpers - Zinoviev, Alexandra Kollontai, Stalin (who was quick to sense the new direction of power in the party), and, most effective of all, Yakov Sverdlov."

The Bolshevik Committee was reorganised. It now included Bukharin, Lenin, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Alexandra Kollontai, Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky, Yakov Sverdlov, Moisei Uritsky, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Andrey Bubnov, Grigori Sokolnikov, Alexei Rykov, Viktor Nogin, Ivan Smilga and V. P. Milyutin. Lenin arranged for two of his supporters, Stalin and Sokolnikov, to become co-editors of Pravada.

In September 1917, Lenin sent a message to the Bolshevik Central Committee via Ivar Smilga. "Without losing a single moment, organize the staff of the insurrectionary detachments; designate the forces; move the loyal regiments to the most important points; surround the Alexandrinsky Theater (i.e., the Democratic Conference); occupy the Peter-Paul fortress; arrest the general staff and the government; move against the military cadets, the Savage Division, etc., such detachments as will die rather than allow the enemy to move to the center of the city; we must mobilize the armed workers, call them to a last desperate battle, occupy at once the telegraph and telephone stations, place our staff of the uprising at the central telephone station, connect it by wire with all the factories, the regiments, the points of armed fighting, etc."

Joseph Stalin read the message to the Central Committee. Nickolai Bukharin later recalled: "We gathered and - I remember as though it were just now - began the session. Our tactics at the time were comparatively clear: the development of mass agitation and propaganda, the course toward armed insurrection, which could be expected from one day to the next. The letter read as follows: 'You will be traitors and good-for-nothings if you don't send the whole (Democratic Conference Bolshevik) group to the factories and mills, surround the Democratic Conference and arrest all those disgusting people!' The letter was written very forcefully and threatened us with every punishment. We all gasped. No one had yet put the question so sharply. No one knew what to do. Everyone was at a loss for a while. Then we deliberated and came to a decision. Perhaps this was the only time in the history of our party when the Central Committee unanimously decided to burn a letter of Comrade Lenin's. This instance was not publicized at the time." Lev Kamenev proposed replying to Lenin with an outright refusal to consider insurrection, but this step was turned down. Eventually it was decided to postpone any decision on the matter.

After the fall of the Provisional Government Bukharin worked closely with Mikhail Frunze to gain control of Moscow. At this time Bukharin was acknowledged as the leader of the Left Communists. This resulted in him disagreeing with Lenin over both internal economic and external revolutionary radicalism. Nikita Khrushchev saw Bukharin speak in 1919 when I was serving in the Red Army. "Everyone was very pleased with him, and I was absolutely spellbound. He had an appealing personality and a strong democratic spirit."

By 1921 the Kronstadt sailors had become disillusioned with the Bolshevik government. They were angry about the lack of democracy and the policy of War Communism. On 28th February, 1921, the crew of the battleship, Petropavlovsk, passed a resolution calling for a return of full political freedoms. Lenin denounced the Kronstadt Uprising as a plot instigated by the White Army and their European supporters.

On 6th March, Leon Trotsky announced that he was going to order the Red Army to attack the Kronstadt sailors. However, it was not until the 17th March that government forces were able to take control of Kronstadt. An estimated 8,000 people (sailors and civilians) left Kronstadt and went to live in Finland. Official figures suggest that 527 people were killed and 4,127 were wounded. Historians who have studied the uprising believe that the total number of casualties was much higher than this. According to Victor Serge over 500 sailors at Kronstadt were executed for their part in the rebellion.

Most Bolshevik leaders accepted Lenin's version of events. Bukharin was one of those who disapproved of this action and at the Third Comintern Congress in 1922 he argued: "Who says that the Kronstadt rising was White? No. For the sake of the idea, for the sake of our task, we were forced to suppress the revolt of our erring brothers. We cannot look upon Kronstadt sailors as our enemies. We love them as our true brothers, our own flesh and blood."

Bukharin gradually moderated his left-wing views and by December 1922 Lenin admitted: "Bukharin is not only the most valuable theoretician of the Party, as he is the biggest, but he also may be considered the favourite of the whole Party. But his theoretical views can with only the greatest reservations be regarded as fully Marxist, for there is something scholastic in him." Simon Sebag Montefiore, the author of Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003), described him as "all twinkling eyes and reddish beard, a painter, poet and philosopher" and charmed Joseph Stalin so much that he was admitted into his "magic circle".

Roy A. Medvedev, has argued in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) that on the surface it was a strange decision: "In 1922 Stalin was the least prominent figure in the Politburo. Not only Lenin but also Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, and A. I. Rykov were much more popular among the broad masses of the Party than Stalin. Closemouthed and reserved in everyday affairs, Stalin was also a poor public speaker. He spoke in a low voice with a strong Caucasian accent, and found it difficult to speak without a prepared text. It is not surprising that, during the stormy years of revolution and civil war, with their ceaseless meetings, rallies, and demonstrations, the revolutionary masses saw or heard little of Stalin."

When Lenin died in 1924 Joseph Stalin, Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev became the dominant figures in the Soviet government. Bukharin was now seen as the leader of the right-wing of the party. He now rejected the idea of world revolution and argued that the party's main priority should be to defend the communist system that had been developed in the Soviet Union.

Bukharin's economic policies also became more conservative and he began advocating a policy of gradualism. He argued that socialism in the Soviet Union could evolve only over a long period of gestation. His agricultural policies were also controversial. Bukharin's theory was that the small farmers only produced enough food to feed themselves. The large farmers, on the other hand, were able to provide a surplus that could be used to feed the factory workers in the towns. To motivate the kulaks to do this, they had to be given incentives, or what Bukharin called, "the ability to enrich" themselves.

Lenin in the past often asserted that a socialist society could not be constructed in a single country. Leon Trotsky agreed and described it as an "elementary Marxist truth". Bukharin disagreed and claimed that "all the conditions for building socialism already exists in Russia". Trotsky was not too surprised by Bukharin changing his view on the need for world revolution: He wrote in My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930) that "Bukharin's nature is such that he must always attach himself to someone. He becomes, in such circumstances, nothing more than a medium for someone else's actions and speeches. You must always keep your eyes on him, or else he will succumb quite imperceptibly to the influence of someone directly opposed to you... And then he will deride his former idol with that same boundless enthusiasm with which he has just been lauding him to the skies. I never took Bukharin too seriously and I left him to himself, which really means, to others. after the death of Lenin he became Zinoviev's medium, and then Stalin's."

Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004), argued: "Stalin and Bukharin rejected Trotsky and the Left Opposition as doctrinaires who by their actions would bring the USSR to perdition... Zinoviev and Kamenev felt uncomfortable with so drastic a turn towards the market economy... They disliked Stalin's movement to a doctrine that socialism could be built in a single country - and they simmered with resentment at the unceasing accumulation of power by Stalin."

In 1925 Joseph Stalin switched his support from Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev to Bukharin and now began advocating the economic policies of Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov. The historian, Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has pointed out: "Tactical reasons compelled him to join hands with the spokesmen of the right, on whose vote in the Politburo he was dependent. He also felt a closer affinity with the men of the new right than with his former partners. Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky accepted his socialism in one country, while Zinoviev and Kamenev denounced it. Bukharin may justly be regarded as the co-author of the doctrine. He supplied the theoretical arguments for it and he gave it that scholarly polish which it lacked in Stalin's more or less crude version."

Stalin wanted an expansion of the New Economic Policy that had been introduced several years earlier. Farmers were allowed to sell food on the open market and were allowed to employ people to work for them. Those farmers who expanded the size of their farms became known as kulaks. Bukharin believed the NEP offered a framework for the country's more peaceful and evolutionary "transition to socialism". He disregarded traditional party hostility to kulaks and called on them to "enrich themselves".

When Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev eventually began attacking his policies, Joseph Stalin argued they were creating disunity in the party and managed to have them expelled from the Central Committee. The belief that the party would split into two opposing factions was a strong fear amongst active communists in the Soviet Union. They were convinced that if this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union.

In the spring of 1927 Leon Trotsky drew up a proposed programme signed by 83 oppositionists. He demanded a more revolutionary foreign policy as well as more rapid industrial growth. He also insisted that a comprehensive campaign of democratisation needed to be undertaken not only in the party but also in the soviets. Trotsky added that the Politburo was ruining everything Lenin had stood for and unless these measures were taken, the original goals of the October Revolution would not be achievable.

Stalin and Bukharin led the counter-attacks through the summer of 1927. At the plenum of the Central Committee in October, Stalin pointed out that Trotsky was originally a Menshevik: "In the period between 1904 and the February 1917 Revolution Trotsky spent the whole time twirling around in the company of the Mensheviks and conducting a campaign against the party of Lenin. Over that period Trotsky sustained a whole series of defeats at the hands of Lenin's party." Stalin added that previously he had rejected calls for the expulsion of people like Trotsky and Zinoviev from the Central Committee. "Perhaps, I overdid the kindness and made a mistake."

Stalin argued that there was a danger that the party would split into two opposing factions. If this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. On 14th November 1927, the Central Committee decided to expel Leon Trotsky and Gregory Zinoviev from the party. This decision was ratified by the Fifteenth Party Congress in December. The Congress also announced the removal of another 75 oppositionists, including Lev Kamenev.

In December 1927 it was reported to Joseph Stalin that the Soviet Union faced a severe shortfall in grain supplies. On 6th January, 1928, Stalin sent out a secret directive threatening to sack local party leaders who failed to apply "tough punishments" to those guilty of "grain hoarding". During that winter Stalin began attacking kulaks for not supplying enough food for industrial workers. He also advocated the setting up of collective farms. The proposal involved small farmers joining forces to form large-scale units. In this way, it was argued, they would be in a position to afford the latest machinery. Stalin believed this policy would lead to increased production. However, the peasants liked farming their own land and were reluctant to form themselves into state collectives.

Stalin was furious that the peasants were putting their own welfare before that of the Soviet Union. Local communist officials were given instructions to confiscate kulaks property. This land was then used to form new collective farms. There were two types of collective farms in the 1920s. The sovkhoz (land was owned by the state and the workers were hired like industrial workers) and the kolkhoz (small farms where the land was rented from the state but with an agreement to deliver a fixed quota of the harvest to the government).

Stalin blamed Bukharin and the New Economic Policy for the failures in agriculture. Bukharin feared that he would be removed from power and made overtures to Lev Kamenev to prevent this. "The disagreements between us and Stalin are many times more serious than the ones we had with you. We (those of the right of the party) wanted Kamenev and Zinoviev restored to the Politburo." This placed Bukharin in great danger as Stalin's agents were listening to his telephone conversations.

Bukharin also wrote an article, Notes of an Economist, where he criticised what he called the Five Year Plan as "super-industrialisation". According to Bukharin, this policy was "Trotskyist and anti-Leninist". He argued that only a "balanced, steady relationship between the interests of industry and agriculture would secure healthy economic development". Stalin disagreed with Bukharin. He believed that fast industrial progress would provide military security. Stalin felt so strongly about this that he was willing to crush anyone who stood in the way of the policy.

Bukharin also clashed with Stalin over foreign policy. At the Comintern's Sixth Congress in July 1928, Stalin declared that anti-communist socialists in Europe (members of labour and social-democratic parties) were the deadliest enemies of socialism and described them as "social-fascists". Bukharin wanted communists and socialists to unite against the fascist menace in Italy and Germany. However, Stalin had little difficulty in persuading the rest of the Politburo that he was right.

In the spring of 1928, Joseph Stalin began dismissing local officials who were known to supporters of Bukharin. At the same time, Stalin made speeches attacking the kulaks for not supplying enough food for the industrial workers. Bukharin was furious and sought help from Alexei Rykov and Maihail Tomsky, in an effort to combat Stalin. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out: "In spring 1928 Bukharin mobilized his supporters, Rykov, then head of government, and the Trades Union leader Tomsky, and they all wrote notes to the Politburo about the threat to the alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry, naturally invoking Lenin. Stalin did not intend to annihilate Bukharin just yet. He was making a 180-degree turn, and needed Bukharin to explain it from the standpoint of Marxism."

In meetings of the Politburo, Bukharin was joined by Rykov and Tomsky in opposing Stalin's agricultural policy. However, Mikhail Kalinin and Kliment Voroshilov, after initially supporting Bukharin, backed down under pressure from Stalin. At these meetings Stalin argued that the kulaks were a class that needed to be destroyed: "The advance toward socialism inevitably leads to resistance on the part of the exploiting classes... When class war is waged there has to be terror. If class war is intensified - the terror must also be intensified." Stalin called Bukharin to his office and suggested a deal: "You and I are the Himalayas - all the others are nonentities. Let's reach an understanding." However, Bukharin refused to back-down, but agreed to refrain from making speeches or writing articles on this subject in fear of being accused of dividing the party.

In July, 1928, Bukharin went to see Lev Kamenev. He told him that he now realized that Joseph Stalin had played one group off against the other to gain complete power for himself: "He is an unprincipled intriguer who subordinates everything to his appetite for power. At any given moment he will change his theories in order to get rid of someone," Bukharin told Kamenev. He went on to claim that Stalin would eventually destroy the communist revolution. "Our disagreements with Stalin are far, far, more serious than those we have with you," he argued and suggested that they should join forces to end Stalin's dictatorship of the party.

In November, 1929, Nickolai Bukharin, was removed from the Politburo. Stalin now decided to declare war on the kulaks. The following month he made a speech where he argued: "Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes… Now dekulakisation is being undertaken by the masses of the poor and middling peasant masses themselves, who are realising total collectivisation. Now dekulakisation in the areas of total collectivisation is not just a simple administrative measure. Now dekulakisation is an integral part of the creation and development of collective farms. When the head is cut off, no one wastes tears on the hair."

On 30th January 1930 the Politburo approved the liquidation of kulaks as a class. Vyacheslav Molotov was put in charge of the operation. According to Simon Sebag Montefiore, the author of Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003), the kulaks were divided into three categories: "The first category… to be immediately eliminated; the second to be imprisoned in camps; the third, 150,000 households, to be deported. Molotov oversaw the death squads, the railway carriages, the concentration camps like a military commander. Between five and seven million people ultimately fitted into the three categories." Thousands of kulaks were executed and an estimated five million were deported to Siberia or Central Asia. Of these, approximately twenty-five per cent perished by the time they reached their destination.

In 1929 Bukharin was deprived of the chairmanship of the Comintern and expelled from the Politburo. He now began work as editor of Izvestia. He now loyally supported the policies of Joseph Stalin. However, when he visited Theodore and Lydia Dann in Paris in 1935 he was very critical of Stalin: "It even makes him miserable that he cannot convince everyone, including himself, that he is a taller man than anybody else. That is his misfortune; it may be his most human trait and perhaps his only human trait; but his reaction to his 'misfortune' is not human - it is almost devilish; he cannot help taking revenge for it on others, any others, but especially those who are in some way better or more gifted than he is... Any man who speaks better than he does is doomed; Stalin will not permit him to live, for this man will serve as an eternal reminder that he is not the first, not the best speaker; if any man writes better than he does, he is in trouble, for Stalin, and only Stalin, must be the greatest Russian writer... Yes, yes, he is a small, malignant man - or rather not a man but a devil."

Bukharin attempted to explain why Stalin was still popular in the Soviet Union: "It is not him we trust but the man in whom the party has reposed its confidence. It just so happened that he has become a sort of a symbol of the party. The lower classes, the workers, the people trust him; this may be our fault, but that's what has happened. That's why we all put our heads in his mouth... knowing for sure that one day he will gobble us up. He knows it, too, and merely waits for a propitious moment."

Nikolai Bukharin was arrested and charged with treason in 1937. Raphael R. Abramovitch, the author of The Soviet Revolution: 1917-1939 (1962) pointed out that at his trial: "Bukharin, who still had a little fight left in him, was extinguished by the concerted efforts of the public prosecutor, the presiding judge, GPU agents and former friends. Even a strong and proud man like Bukharin was unable to escape the traps set for him. The trial took its usual course, except that one session had to be hastily adjourned when Krestinsky refused to follow the script. At the next session, he was compliant."

Nikolai Bukharin was executed on 15th March, 1938.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1924 Nikolai Bukharin wrote an autobiography for The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution.

Emigration marked a new phase in my life, from which I benefited in three ways. Firstly, I lived with workers' families and spent whole days in libraries. If I had acquired my general knowledge and a quite detailed understanding of the agrarian question in Russia, it was undoubtedly the Western libraries that provided me with essential intellectual capital. Secondly, I met Lenin, who of course had an enormous influence on me. Thirdly, I learnt languages and gained practical experience of the labour movement.

(2) Nikita Khrushchev, autobiography published in 1971.

I saw Bukharin speak in 1919 when I was serving in the Red Army. Everyone was very pleased with him, and I was absolutely spellbound. He had an appealing personality and a strong democratic spirit. Bukharin was also the editor of Pravda. He was the Party's chief theoretician. Lenin always spoke affectionately of him as "Our Bukharchik". On Lenin's instructions he wrote The ABC of Communism, and everyone who joined the Party learned Marxist-Lenist science by studying Bukharin's work.

(3) Vladimir Lenin, testament dictated on 25th December, 1922.

Of the younger members of the Central Committee, I want to say a few words about Piatakov and Bukharin. They are, in my opinion, the most able forces (among the youngest). In regard to them it is necessary to bear in mind the following: Bukharin is not only the most valuable theoretician of the Party, as he is the biggest, but he also may be considered the favourite of the whole Party. But his theoretical views can with only the greatest reservations be regarded as fully Marxist, for there is something scholastic in him.

(4) In his book Stalin, Isaac Deutscher described the way Joseph Stalin switched his support to Nikolai Bukharin.

Tactical reasons compelled him to join hands with the spokesmen of the right, on whose vote in the Politburo he was dependent. He also felt a closer affinity with the men of the new right than with his former partners. Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky accepted his socialism in one country, while Zinoviev and Kamenev denounced it. Bukharin may justly be regarded as the co-author of the doctrine. He supplied the theoretical arguments for it and he gave it that scholarly polish which it lacked in Stalin's more or less crude version.

(5) Nikolay Bukharin, in conversation with Theodore and Lydia Dann (1935)

It even makes him miserable that he cannot convince everyone, including himself, that he is a taller man than anybody else. That is his misfortune; it may be his most human trait and perhaps his only human trait; but his reaction to his 'misfortune' is not human - it is almost devilish; he cannot help taking revenge for it on others, any others, but especially those who are in some way better or more gifted than he is...

Any man who speaks better than he does is doomed; Stalin will not permit him to live, for this man will serve as an eternal reminder that he is not the first, not the best speaker; if any man writes better than he does, he is in trouble, for Stalin, and only Stalin, must be the greatest Russian writer... Yes, yes, he is a small, malignant man - or rather not a man but a devil...

It is not him we trust but the man in whom the party has reposed its confidence. It just so happened that he has become a sort of a symbol of the party. The lower classes, the workers, the people trust him; this may be our fault, but that's what has happened. That's why we all put our heads in his mouth... knowing for sure that one day he will gobble us up. He knows it, too, and merely waits for a propitious moment.

(6) Raphael R. Abramovitch, The Soviet Revolution: 1917-1939 (1962)

Bukharin, who still had a little fight left in him, was extinguished by the concerted efforts of the public prosecutor, the presiding judge, GPU agents and former friends. Even a strong and proud man like Bukharin was unable to escape the traps set for him. The trial took its usual course, except that one session had to be hastily adjourned when Krestinsky refused to follow the script. At the next session, he was compliant. All the defendants were condemned to death and shot.

(7) Freda Kirchwey, The Nation (March, 1938)

The trial of Bukharin and his fellow oppositionists has broken about the ears of the world like the detonation of a bomb. One can hear the cracking of liberal hopes; of the dream of anti-fascist unity; of a whole system of revolutionary philosophy wherever democracy is threatened, the significance of the trial will be anxiously weighed.

In spite of the trials, I believe Russia is dependable; that it wants peace, and will join in any joint effort to check Hitler and Mussolini, and will also fight if necessary. Russia is still the strongest reason for hope.