Kronstadt Uprising

The sailors at the Kronstadt naval base had long been a source of radical dissent. On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship. This was the beginning of the 1905 Russian Revolution. (1)

Mutinies had taken place during the 1905 Revolution and played an important role in persuading Nicholas II to issue his October Manifesto. The Kronstadt sailors were also active in the formation of one of the most important Soviets in the summer of 1917. Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for of the Manchester Guardian, went to interview the President of the Kronstadt Workers', Soldiers' and Sailors Soviet. "The soldiers and sailors were treated on this island like dogs. They were worked from early morning till late at night. They were not allowed any recreations for fear that they would associate for political purposes. Nowhere could you study the slavery system of capitalist imperialism better than here. For the smallest misdemeanor a man was put in chains, and if he was found with a Socialist pamphlet in his possession he was shot." (2)

On 24th October, 1917, Lenin wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already, putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested, the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for delay, when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything." (3)

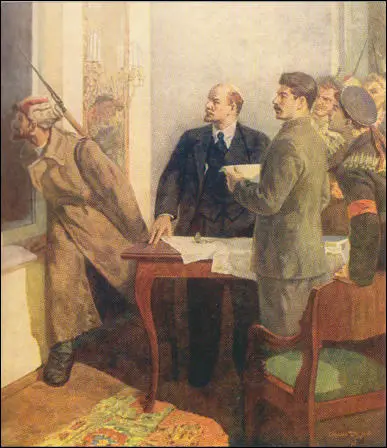

Leon Trotsky supported Lenin's view and urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The Smolny Institute became the headquarters of the revolution and was transformed into a fortress. Trotsky reported that the "chief of the machine-gun company came to tell me that his men were all on the side of the Bolsheviks". (4)

The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Alexander Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. The Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace. (5)

Leon Trotsky later admitted the Kronstadt sailors played an important role in the Russian Revolution. However, by 1921 the Kronstadt sailors had become disillusioned with the Bolshevik government. They were angry about the lack of democracy, the Red Terror and the policy of War Communism. The Soviet historian, David Shub, has argued: "On 1 March 1921, the sailors of Kronstadt revolted against Lenin. Mass meetings of 15,000 men from various ships and garrisons passed resolutions demanding immediate new elections to the Soviet by secret ballot; freedom of speech and the press for all left-wing Socialist parties; freedom of assembly for trade unions and peasant organizations; abolition of Communist political agencies in the Army and Navy; immediate withdrawal of all grain requisitioning squads, and re-establishment of a free market for the peasants." (6)

On 28th February, 1921, the crew of the battleship, Petropavlovsk, passed a resolution calling for a return of full political freedoms. It was reported by Radio Moscow: that the sailors were supporters of the White Army: "Just like other White Guard insurrections, the mutiny of General Kozlovsky and the crew of the battleship Petropavlovsk has been organised by Entente spies. The French counter espionage is mixed up in the whole affair. History is repeating itself. The Socialist Revolutionaries, who have their headquarters in Paris, are preparing the ground for an insurrection against the Soviet power." (7)

I response to this broadcast the Kronstadt sailors issued the following statement: "Comrade workers, red soldiers and sailors. We stand for the power of the Soviets and not that of the parties. We are for free representation of all who toil. Comrades, you are being misled. At Kronstadt all power is in the hands of the revolutionary sailors, of red soldiers and of workers. It is not in the hands of White Guards, allegedly headed by a General Kozlovsky, as Moscow Radio tells you." (8)

Eugene Lyons, the author of Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967), pointed out that this protest was highly significant because of Kronstadt's revolutionary past: "The hundreds of large and small uprisings throughout the country are too numerous to list, let alone describe here. The most dramatic of them, in Kronstadt, epitomizes most of them. What gave it a dimension of supreme drama was the fact that the sailors of Kronstadt, an island naval fortress near Petrograd, on the Gulf of Finland, had been one of the main supports of the putsch. Now Kronstadt became the symbol of the bankruptcy of the Revolution. The sailors on the battleships and in the naval garrisons were in the final analysis peasants and workers in uniform." (9)

Lenin denounced the Kronstadt Uprising as a plot instigated by the White Army and their European supporters. However, in private he realised that he was under attack from the left. He was particularly concerned by the "scene of the rising was Kronstadt, the Bolshevik stronghold of 1917". Isaac Deutscher claims that Lenin commented: "This was the flash which lit up reality better than anything else." (10)

On 6th March, 1921, Leon Trotsky issued a statement: "I order all those who have raised a hand against the Socialist Fatherland, immediately to lay down their weapons. Those who resist will be disarmed and put at the disposal of the Soviet Command. The arrested commissars and other representatives of the Government must be freed immediately. Only those who surrender unconditionally will be able to count on the clemency of the Soviet Republic." (11)

Trotsky then ordered the Red Army to attack the Kronstadt sailors. According to one official report, some members of the Red Army refused to attack the naval base. "At the beginning of the operation the second battalion had refused to march. With much difficulty and thanks to the presence of communists, it was persuaded to venture on the ice. As soon as it reached the first south battery, a company of the 2nd battalion surrendered. The officers had to return alone." (12)

Felix Dzerzhinsky, the head of Cheka, was also involved in putting down the uprising, as the loyalty of the Red Army soldiers were in doubt. Victor Serge pointed out: "Lacking any qualified officers, the Kronstadt sailors did not know how to employ their artillery; there was, it is true, a former officer named Kozlovsky among them, but he did little and exercised no authority. Some of the rebels managed to reach Finland. Others put up a furious resistance, fort to fort and street to street.... Hundreds of prisoners were taken away to Petrograd and handed to the Cheka; months later they were still being shot in small batches, a senseless and criminal agony. Those defeated sailors belonged body and soul to the Revolution; they had voiced the suffering and the will of the Russian people. This protracted massacre was either supervised or permitted by Dzerzhinsky." (13)

Some observers claimed that many of the victims would die shouting, "Long live the Communist International!" and "Long live the Constituent Assembly!" It was not until the 17th March that government forces were able to take control of Kronstadt. Alexander Berkman, wrote: "Kronstadt has fallen today. Thousands of sailors and workers lie dead in its streets. Summary execution of prisoners and hostages continues." (14)

An estimated 8,000 people (sailors and civilians) left Kronstadt and went to live in Finland. Official figures suggest that 527 people were killed and 4,127 were wounded. "These figures do not include the drowned, or the numerous wounded left to die on the ice. Nor do they include the victims of the Revolutionary Tribunals." Historians who have studied the uprising believe that the total number of casualties was much higher than this. It is claimed that over 500 sailors at Kronstadt were executed for their part in the rebellion. (15)

Nikolai Sukhanov reminded Leon Trotsky that three years previously he had told the people of Petrograd: "We shall conduct the work of the Petrograd Soviet in a spirit of lawfulness and of full freedom for all parties. The hand of the Presidium will never lend itself to the suppression of the minority." Trotsky lapsed into silence for a while, then said wistfully: "Those were good days." Walter Krivitsky, who was a Cheka agent during this period claimed that when Trotsky put down the Kronstadt Uprising the Bolshevik government lost contact with the revolution and from then on it would be a path of state terror and dictatorial rule. (16)

Alexander Berkman decided to leave the Soviet Union after the Kronstadt Rising: "Grey are the passing days. One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death; the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness.... I have decided to leave Russia." (17)

Leon Trotsky later blamed Nestor Makhno and the anarchists for the uprising. "Makhno... was a mixture of fanatic and adventurer. He became the concentration of the very tendencies which brought about the Kronstadt Uprising. Makhno created a cavalry of peasants who supplied their own horses. They were not downtrodden village poor whom the October Revolution first awakened, but the strong and well-fed peasants who were afraid of losing what they had. The anarchist ideas of Makhno (the ignoring of the State, non-recognition of the central power) corresponded to the spirit of the kulak cavalry as nothing else could. I should add that the hatred of the city and the city worker on the part of the followers of Makhno was complemented by the militant anti-Semitism." (18)

Trotsky also accused Felix Dzerzhinsky of being responsible for the massacre: "The truth of the matter is that I personally did not participate in the least in the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion, nor in the repressions following the suppression. In my eyes this very fact is of no political significance. I was a member of the government, I considered the quelling of the rebellion necessary and therefore bear responsibility for the suppression. Concerning the repressions, as far as I remember, Dzerzhinsky had personal charge of them and Dzerhinsky could not tolerate anyone's interference with his functions (and properly so). Whether there were any needless victims I do not know. On this score I trust Dzerzhinsky more than his belated critics." (19)

Primary Sources

(1) Morgan Philips Price, Manchester Guardian (17th July, 1917)

In a large house in the main street I found the headquarters of the Kronstadt Soviet. With some little misgiving I passed by the sentries and asked to see the President. I was taken into a room, where I saw a young man with a red badge on his coat looking through some papers, who appeared to be a student. He had long hair and dreamy eyes, with a far-off look of an idealist. This was the elected President of the Kronstadt Workers', Soldiers' and Sailors Soviet.

"Be seated," he said. "I suppose you have come down here from Petrograd to see if all the stories about our terror are true. You will probably have observed that there is nothing extraordinary going on here; we are simply putting this place into order after the tyranny and chaos of the late Tsarist regime. The workmen, soldiers and sailors here find that they can do this job better by themselves than by leaving it to people who call themselves democrats, but are really friends of the old regime. That is why we have declared the Kronstadt Soviet the supreme authority in the island."

"The soldiers and sailors were treated on this island like dogs. They were worked from early morning till late at night. They were not allowed any recreations for fear that they would associate for political purposes. Nowhere could you study the slavery system of capitalist imperialism better than here. For the smallest misdemeanor a man was put in chains, and if he was found with a Socialist pamphlet in his possession he was shot."

I was taken to a prison on the south side of the island, where were kept the former military police, gendarmes, police spies and provocateurs of fallen Tsarism. The quarters were very bad, and many of the cells had no windows at all.

I met a Major-General, formerly in command of the fortress artillery of Kronstadt. He stood in his shirt-sleeves - no medalled tunic decorated his breast any more. His red-striped trousers of Prussian blue bore signs of three months' wear in confinement. Sheepishly he looked at me, as if uncertain whether it was dignified for him to tell his troubles to a stray foreigner.

"I wish they would bring some indictment against us," he said at length, "for to sit here for three months and not to know what our fate is to be is rather hard." "And I sat here, not three months, but three years," broke in the sailor guard who was taking us round, "and I didn't know what was going to happen to me, although my only offence was that I had been distributing a pamphlet on the life of Karl Marx."

I pointed out to the sailor that the prison accommodation was unfit for a human being. He answered, "Well, I sat here all that time because of these gentlemen, and I think that if they had known they were going to sit here they would have made better prisons!"

(2) Resolution of political demands passed by the crew of the Petropavlovsk on 8th February, 1921.

(1) Immediate new elections to the Soviets. The present Soviets no longer express the wishes of the workers and the peasants. The new elections should be by secret ballot, and should be preceded by free electoral propaganda.

(2) Freedom of speech and of the press for workers and peasants, for the Anarchists, and the Left Socialist parties.

(3) The right of assembly, and freedom for trade union and peasant organizations.

(4) The organization, at the latest on 10th March 1921, of a Conference of non-Party workers, soldiers and sailors of Petrograd, Kronstadt and the Petrograd District.

(5) The liberation of all political prisoners of the Socialist parties, and for all imprisoned workers and peasants, soldiers and sailors belonging to workers and peasant organizations.

(6) The election of a commission to look into the dossiers of all those detained in prisons and concentration camps.

(7) The abolition of all political sections in the armed forces. No political party should have privileges for the propagation of its ideas, or receive State subsidies to this end. In the place of the political sections, various cultural groups should be set up, deriving resources from the State.

(8) The immediate abolition of the militia detachments set up between towns and countryside.

(9) The equalization of rations for all workers, except those engaged in dangerous or unhealthy jobs.

(10) The abolition of Party combat detachments in all military groups. The abolition of Party guards in factories and enterprises. If guards are required, they should be nominated, taking into account the views of the workers.

(11) The granting of the peasants of freedom of action on their own soil, and of the right to own cattle, provided they look after them themselves and do not employ hired labour.

(12) We request that all military units and officer trainee groups associate themselves with this resolution.

(3) Moscow Radio broadcast (3rd March, 1921)

Just like other White Guard insurrections, the mutiny of General Kozlovsky and the crew of the battleship Petropavlovsk has been organised by Entente spies. The French counter espionage is mixed up in the whole affair. History is repeating itself. The Socialist Revolutionaries, who have their headquarters in Paris, are preparing the ground for an insurrection against the Soviet power.

(4) Kronstadt Provisionary Revolutionary Committee (4th March, 1921)

Comrade workers, red soldiers and sailors. We stand for the power of the Soviets and not that of the parties. We are for free representation of all who toil. Comrades, you are being misled. At Kronstadt all power is in the hands of the revolutionary sailors, of red soldiers and of workers. It is not in the hands of White Guards, allegedly headed by a General Kozlovsky, as Moscow Radio tells you.

(5) Leon Trotsky, message sent by radio to the Kronstadt sailors (6th March, 1921)

I order all those who have raised a hand against the Socialist Fatherland, immediately to lay down their weapons. Those who resist will be disarmed and put at the disposal of the Soviet Command. The arrested commissars and other representatives of the Government must be freed immediately. Only those who surrender unconditionally will be able to count on the clemency of the Soviet Republic.

(6) Report on the 561 Infantry Regiment that was used against the Kronstadt sailors (March, 1921)

At the beginning of the operation the second battalion had refused to march. With much difficulty and thanks to the presence of communists, it was persuaded to venture on the ice. As soon as it reached the first south battery, a company of the 2nd battalion surrendered. The officers had to return alone.

(7) Leon Trotsky in a speech to the Second Congress of the Communist Youth International (14th July, 1921)

Two or three days more and the Baltic Sea would have been ice-free and the war vessels of the foreign imperialists could have entered the ports of Kronstadt and Petrograd. Had we then been compelled to surrender Petrograd, it would have opened the road to Moscow, for there are virtually no defensive points between Petrograd and Moscow.

(8) Alexander Berkman, diary entries while living in Russia (March, 1921)

7th March, 1921: Distant rumbling reaches my ears as I cross the Nevsky. It sounds again, stronger and nearer, as if rolling toward me. All at once I realize the artillery is being fired. It is 6 p.m. Kronstadt has been attacked! My heart is numb with despair; something has died within me.

17th March, 1921: Kronstadt has fallen today. Thousands of sailors and workers lie dead in its streets. Summary execution of prisoners and hostages continues.

30th September, 1921: One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under the foot. The revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness. The Bolshevik myth must be destroyed. I have decided to leave Russia.

(9) Victor Serge, along with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, had attempted to mediate between the Kronstadt sailors and the Soviet government. His account of the uprising appeared in his book Memoirs of a Revolutionary.

The final assault was unleashed by Tukhacevsky on 17 March, and culminated in a daring victory over the impediment of the ice. Lacking any qualified officers, the Kronstadt sailors did not know how to employ their artillery; there was, it is true, a former officer named Kozlovsky among them, but he did little and exercised no authority. Some of the rebels managed to reach Finland. Others put up a furious resistance, fort to fort and street to street; they stood and were shot crying, "Long live the world revolution! Hundreds of prisoners were taken away to Petrograd and handed to the Cheka; months later they were still being shot in small batches, a senseless and criminal agony. Those defeated sailors belonged body and soul to the Revolution; they had voiced the suffering and the will of the Russian people. This protracted massacre was either supervised or permitted by Dzerzhinsky.

(10) In March, 1937, Leon Trotsky, wrote an article, Amoralism and Kronstadt , where he replied to charges made by Wendelin Thomas, that Bolshevism and Stalinism were closely linked. Thomas used the example of how Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin, dealt with opponents such as the Mensheviks, the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Kronstadt Rebellion.

Your evaluation of the Kronstadt Uprising of 1921 is basically incorrect. The best, most sacrificing sailors were completely withdrawn from Kronstadt and played an important role at the fronts and in the local Soviets throughout the country. What remained was the grey mass with big pretensions, but without political education and unprepared for revolutionary sacrifice. The country was starving. The Kronstadters demanded privileges. The uprising was dictated by a desire to get privileged food rations.

No less erroneous is your estimate of Makhno. In himself he was a mixture of fanatic and adventurer. He became the concentration of the very tendencies which brought about the Kronstadt Uprising. Makhno created a cavalry of peasants who supplied their own horses. They were not downtrodden village poor whom the October Revolution first awakened, but the strong and well-fed peasants who were afraid of losing what they had.

The anarchist ideas of Makhno (the ignoring of the State, non-recognition of the central power) corresponded to the spirit of the kulak cavalry as nothing else could. I should add that the hatred of the city and the city worker on the part of the followers of Makhno was complemented by the militant anti-Semitism.

(11) Leon Trotsky, The Kronstadt Rebellion (July, 1938)

The truth of the matter is that I personally did not participate in the least in the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion, nor in the repressions following the suppression. In my eyes this very fact is of no political significance. I was a member of the government, I considered the quelling of the rebellion necessary and therefore bear responsibility for the suppression.

Concerning the repressions, as far as I remember, Dzerzhinsky had personal charge of them and Dzerhinsky could not tolerate anyone's interference with his functions (and properly so). Whether there were any needless victims I do not know. On this score I trust Dzerzhinsky more than his belated critics. Victor Serge's conclusions on this score - from third hand - have no value in my eyes. But I am ready to recognize that civil war is no school of humanism. Idealists and pacifists always accused the revolution of "excesses". But the main point is that "excesses" flow from the very nature of the revolution which in itself is but an "excess" of history.

(12) David Shub, Lenin (1948)

Kronstadt was the proudest bastion of the Bolshevik Revolution. The sailors of the island fortress off Petrograd had marched against Kerensky in July 1917 and had stormed the Winter Palace in November to install Lenin in power. Later, when Red Petrograd was threatened by General Yudenich, the Kronstadt sailors had rallied to the defence of the Soviet regime.

On 1 March 1921, the sailors of Kronstadt revolted against Lenin. Mass meetings of 15,000 men from various ships and garrisons passed resolutions demanding immediate new elections to the Soviet by secret ballot; freedom of speech and the press for all left-wing Socialist parties; freedom of assembly for trade unions and peasant organizations; abolition of Communist political agencies in the Army and Navy; immediate withdrawal of all grain requisitioning squads, and re-establishment of a free market for the peasants.

The Kronstadt revolt came as the climax of a series of rebellions, disturbances and protests embracing large areas of Russia. As a result of "War Communism", Russia in March 1921 was on the verge of economic collapse and new civil war in which foreign intervention played no part. The White Armies had been decisively defeated in the autumn of 1919, and were no longer a factor after the capture and execution of Kolchak and the departure of Denikin early in 1920.

(13) Eugene Lyons, Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967)

The hundreds of large and small uprisings throughout the country are too numerous to list, let alone describe here. The most dramatic of them, in Kronstadt, epitomizes most of them. What gave it a dimension of supreme drama was the fact that the sailors of Kronstadt, an island naval fortress near Petrograd, on the Gulf of Finland, had been one of the main supports of the putsch. Now Kronstadt became the symbol of the bankruptcy of the Revolution. In the sycophantic writings about the glorious "new Russia," Kronstadt, if mentioned at all, is covered up with a few official lies.

The sailors on the battleships and in the naval garrisons were in the final analysis peasants and workers in uniform. Soon enough they shared the disillusionment of the country at large. It was in the local Soviet and in the Kronstadt Communist Party that the spirit of insurgence first found expression, then spread to the naval and civilian population. Kremlin history, then and since, has attempted to dismiss the rebellion as the work of monarchists and emigre capitalists. But it was in the first place an insurrection within the Bolshevik elite itself. Many of the victims would die shouting, "Long live the Communist International!" and "Long live the Constituent Assembly!"

The tragedy began with a mass meeting of fifteen hundred sailors and workers on March 1, 1921. Though Lenin had sent several of his best people - among them - Mikhail Kalinin, well-liked because of his peasant origin and personality - to take part in the proceedings, they could not stave off a resolution condemning the regime. "The present Soviets do not express the will of the workers and peasants," it charged, and went on to ask for "new elections by secret ballot, the pre-election campaign to have full freedom of agitation." The sailors demanded freedom of speech, press, and assembly, liberation of political prisoners, restoration of the peasants' right to the products of their labor - in short, fulfillment of the Bolshevik promises.

Four days later the Kronstadt sailors formed a small committee composed chiefly of communists, which assumed control of the town, the fortress, the ships. A brutally-worded ultimatum by Trotsky as War Commissar, approved by Lenin, called for "unconditional surrender" or the "mutineers" would be shot "like partridges." When the committee refused to yield, Trotsky assigned Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the same General Tukhachevsky who was destined to be killed by Stalin, to take Kronstadt by force. Hundreds of Petrograd workers crossed the ice -the gulf is still frozen at that time of the year - to join the menaced Kronstadters.

Tukhachevsky marched on the naval town with sixty thousand picked troops. Tough Cheka forces were deployed in the rear, ready to shoot army men who might flinch from attacking the heroes of the Revolution. One regiment, in fact, did mutiny, and was whipped back into line. The siege began with an aerial bombardment at 6:45 p.m. on March 6, followed by an artillery barrage. The sailors answered with fire from the fort and from their ships. Then the Red Army advanced across the ice. At several points the ice gave way and hundreds were drowned. In the final days the town was conquered street by street.

Tukhachevsky later declared that in all his years of war and civil war, he bad not witnessed carnage such as he overseered at Kronstadt. "It was not a battle," he said, "it was an inferno. ... The sailors fought like wild beasts. I cannot understand where they found the might for such rage. Each house had to be taken by storm."

On March 17, Tukhachevsky could report to the War Commissar that the job was finished. Kronstadt was a place of death. Eighteen thousand of the rebels, it was estimated, had been killed; thousands of government troops died. Hundreds were arrested and shot in the ensuing "pacification."

The massacre of the sailors signalized the rupture of the last natural bond between the regime and the sons of the people. What remained was a thing alien and hated and cancerous. The totalitarian state had triumphed. Russia was a nation occupied by an internal enemy.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

Who Set Fire to the Reichstag? (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)