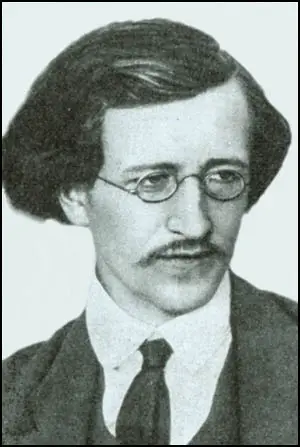

Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko

Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, the son of a military officer, was born in Russia in 1884. he was educated at the Voronezh Military School and the Nikolaevsk Army Engineering College. During this period Antonov-Ovseenko began to question the political system that existed in Russia and in 1901 was expelled from college for refusing to take the oath of loyalty to Nicholas II.

Antonov-Ovseenko moved to Warsaw where he joined the illegal Social Democratic Labour Party. The following year he found work as a labourer in the Alexander Docks in St. Petersburg and then as a coachman for the Society for the Protection of Animals.

At its Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between two of its leaders, Lenin and Julius Martov. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Martov won the vote 28-23 but Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks. Antonov-Ovseenko, along with George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Leon Trotsky, Vera Zasulich, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Noi Zhordania and Fedor Dan, supported Julius Martov.

In August 1904 Antonov-Ovseenko was arrested for distributing illegal political propaganda. He was released and sent to Warsaw where he became a junior officer in the Kolyvan Infantry Regiment. He used his position to recruit junior officers to the Mensheviks.

Antonov-Ovseenko deserted from the army during the 1905 Revolution. He joined the Menshevik Military Committee and edited the underground newspaper Kazarma (Garrison). However, he was arrested in April, 1906, but escaped from Sushchevsky Prison. Captured again in June, he was sentenced to death (later commuted to twenty years hard labour in Siberia).

In June, 1907, a group of Mensheviks freed Antonov-Ovseenko by blowing a hole in the prison wall. He later recalled: "Within a month I was in Sebastopol under orders from the Central Committee to prepare an insurrection. It broke out suddenly in June, and I was arrested in the street as I tried to shoot my way through a cordon of police and soldiers surrounding the house where a meeting of representatives from military units was in progress. I was imprisoned for a year without my true identity being revealed and then I was sentenced to death, which eight days later was commuted to twenty years' hard labour.... On the eve of our departure from Sebastopol, I escaped with twenty others during an excercise period by blowing a hole in the wall and firing on the warders and sentry. This breakout was organized by Comrade Konstantin who had come from Moscow."

Antonov-Ovseenko spent some time hiding in Finland until he could be provided with a false passport that would enable him to return to Russia. Based in Moscow he organized workers' cooperatives and editing illegal newspapers. After two further arrests Antonov-Ovseenko left Russia and went to live in France. He joined other revolutionaries in exile and as well as becoming secretary of the Parisian Labour Bureau wrote for the radical newspaper, Golos (Voice).

Antonov-Ovseenko returned to Russia after the February Revolution. In May he joined the Bolsheviks and soon afterwards was appointed to the party's Central Committee. Antonov-Ovseenko was the main architect of the armed insurrection and led the Red Guards that seized the Winter Palace on the 25th October, 1917. After the October Revolution he was appointed Commissar for Military Affairs in Petrograd and Commisssar of War.

During the Civil War Antonov-Ovseenko commanded the Bolshevik campaign in the Ukraine and organized famine relief in Samara province. Antonov-Ovseenko worked closely with Leon Trotsky and in 1922 he was appointed Chief of Political Administration of the Red Army.

At the Communist Party Congress in 1922 Antonov-Ovseenko attacked Lenin for making political compromises with the kulaks and foreign capitalism. He also supported the idea of permanent revolution and became one of the leaders of the left opposition.

As a supporter of Leon Trotsky Antonov-Ovseenko lost his military command in 1923. To remove him from the political struggle in the Soviet Union, in 1925 Joseph Stalin sent him as ambassador to Czechoslovakia. Later he held similar posts in Lithuania and Poland.

Antonov-Ovseenko was the Soviet consul general in Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War. He arranged for Russian advisers to help the Popular Front government while expanding the influence of the Soviet Union in the country.

When the show trials took place in August 1936, Antonov-Ovseenko was quick to praise Joseph Stalin. He wrote an article in Izvestia entitled "Finish Them Off" where he described Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev as "fascist saboteurs". He added "the only way to talk to them" was to shoot them.

Joseph Stalin was convinced that Antonov-Ovseenko was plotting against him and in August, 1937, he recalled him to the Soviet Union. Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko was arrested and shot without trial in 1939. A fellow cellmate remembered: "He said goodbye to us all, took off his jacket and shoes, gave them to us, and went out to be shot half-undressed."

Primary Sources

(1) The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution was published by the Soviet government in 1924. The encyclopaedia included a collection of autobiographies and biographies of over two hundred people involved in the Russian Revolution. Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko was one of those invited to write his autobiography.

At the beginning of April 1906, I was arrested at a congress of the military organizations. Five days later, Emelian, myself and three other comrades escaped from the Sushchevsky jail by breaking through a wall. Within a month I was in Sebastopol under orders from the Central Committee to prepare an insurrection. It broke out suddenly in June, and I was arrested in the street as I tried to shoot my way through a cordon of police and soldiers surrounding the house where a meeting of representatives from military units was in progress.

I was imprisoned for a year without my true identity being revealed and then I was sentenced to death, which eight days later was commuted to twenty years' hard labour. Within a month, in June 1907, and on the eve of our departure from Sebastopol, I escaped with twenty others during an excercise period by blowing a hole in the wall and firing on the warders and sentry. This breakout was organized by Comrade Konstantin who had come from Moscow.

(2) Nikolai Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution of 1917 (1922)

Antonov-Ovseenko's plan was accepted. It consisted in occupying first of all those parts of the city adjoining the Finland Station: the Vyborg Side, the outskirts of the Petersburg Side, etc. Together with the units arriving from Finland it would then be possible to launch an offensive against the centre of the capital.

Beginning at 2 in the morning the stations, bridges, lighting installations, telegraphs, and telegraphic agency were gradually occupied by small forces brought from the barracks. The little groups of cadets could not resist and didn't think of it. In general the military operations in the politically important centres of the city rather resembled a changing of the guard. The weaker defence force, of cadets retired; and a strengthened defence force, of Red Guards, took its place.

(3) Pavel Manlyantovich was Minister of Justice in the Provisional Government. He was arrested by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko and the Red Guards on 25th October, 1917. He later wrote about the incident in his book, In the Winter Palace (1918)

There was a noise behind the door and it burst open like a splinter of wood thrown out by a wave, a little man flew into the room, pushed in by the onrushing crowd which poured in after him, like water, at once spilled into every corner and filled the room.

"Where are the members of the Provisional Government?"

"The Provisional Government is here," said Kornovalov, remaining seated.

"What do you want?"

"I inform you, all of you, members of the Provisional Government, that you are under arrest. I am Antonov-Ovseenko, chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee."

"Run them through, the sons of bitches! Why waste time with them? They've drunk enough of our blood!" yelled a short sailor, stamping the floor with his rifle."

There were sympathetic replies: "What the devil, comrades! Stick them all on bayonets, make short work of them!"

Antonov-Ovseenko raised his head and shouted sharply: "Comrades, keep calm!" All members of the Provisional Government are arrested. They will be imprisoned in the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul. I'll permit no violence. Conduct yourself calmly. Maintain order! Power is now in your hands. You must maintain order!"

(4) Robert V. Daniels, Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967)

Palchinsky was waiting in the outer room to report the decision to the Bolsheviks. His notes read: "Breakthrough up the stairs. Decision not to fire. Refusal to negotiate. Go out to meet attackers. Antonov now in charge. I am arrested by Antonov and Chudnovsky." The two Bolshevik leaders entered the Malachite Hall alone and demanded that the cadet guards surrender. The cadets handed over their weapons. In the inner room, one of the ministers suggested that they all sit down at the table in a position of official dignity. There they waited helplessly to be arrested.

A moment later, the crowd of attackers with Antonov at its head burst through the door into the cabinet room. Antonov was not the type who would terrify an adversary, and justice Minister Maliantovich was able to form a careful impression of him: "The little man wore his coat hanging open, and a wide-brimmed hat shoved back onto the back of his neck; he had long reddish hair and glasses, a short trimmed moustache and a small beard. His short upper lip pulled up to his nose when he talked. He had colorless eyes and a tired face. For some reason his shirt-front and collar especially attracted my attention and stuck in my memory. A very high starched folded collar propped his chin up. On his soft shirt-front a long necktie crawled up from his vest to his collar. His collar and shirt and cuffs and hands were those of a very dirty man."

Acting Prime Minister Konovalov calmly addressed Antonov: "This is the Provisional Government. What would you like?"

To Antonov's nearsighted eyes the ministers "merged into one pale-grey trembling spot." He shouted, "In the name of the Military Revolutionary Committee I declare you under arrest."

"The members of the Provisional Government submit to violence and surrender to avoid bloodshed," Konovalov replied, amidst the hoots of the Bolshevik crowd. It was 2:10 a.m. on the morning of Thursday, October 26.

On Antonov's demand, the ministers turned over their pistols and papers. Chudnovsky took the roll of those arrested-the whole cabinet except for Kerensky and Prokopovich. This was the first knowledge the attackers had that the chief prize had eluded their grasp, and in their anger some of the soldiers shouted demands to shoot the rest of the ministers. Antonov appointed a guard of the more reliable sailors to march the prisoners down to the square, designated Chudnovsky as commissar of the Palace, and sent a message to Blagonravov at the Peter-Paul fortress to tell him that the government really had surrendered and to order that prison cells be made ready to receive the Provisional Government. "We were placed under arrest," wrote the Minister of Agriculture, Maslov, "and told that we would be taken to the Peter-Paul fortress. We picked up our coats, but Kishkin's was gone. Someone had stolen it. He was given a soldier's coat. A discussion started between Antonov, the soldiers, and the sailors as to whether the ministers should be taken to their destination in automobiles or on foot. It was decided to make them walk. Each of us was guarded by two men. As we walked through the Palace it seemed as if it were filled with the insurrectionists, some of whom were drunk. When we came out on the street we were surrounded by a mob, shouting, threatening ... and demanding Kerensky. The mob seemed determined to take the law into its own hands and one of the ministers was jostled a bit." Bolshevik participants admitted that the crowd was "drunk with victory" and threatened to lynch the terrified captives. A detail of fifty sailors and workers was formed to march them to the fortress.

Antonov started to move off with the group, when suddenly some shots rang out from the opposite side of the square. Everyone scattered, and when the group reassembled, five of the ministers were missing. There were more shouts to kill the rest, but Antonov got the detail moving again in an orderly fashion. Once again, near the Troitsky Bridge, they were fired on from an automobile. It was a car full of Bolsheviks who didn't know about the victory. Antonov jumped on the car and shouted his identity; the sailors swore, and the occupants of the car barely escaped a beating. Finally the group reached the gate of the Peter-Paul fortress, where the five missing ministers turned up with their guards in a car. The ministers were locked into the same damp cells that had once held the enemies of the Tsar.

Within the Palace there was near-chaos. Soldiers started looting the imperial furnishings, until a guard of sailors, workers, and "the most conscious soldiers" were posted to stop them. Other soldiers and sailors broke into the imperial wine cellars and began drinking themselves into a wild frenzy. Troops sent in to stop the orgy got drunk in turn. Finally a detachment of sailors fought their way in and dynamited the source of the trouble. Out on the Palace Square the tumult gradually subsided. Commissar Dzenis wrote, "Order was restored. Guards were posted. The Kexholm Regiment was placed on guard. Towards morning the units dispersed to their barracks, the detachments of Red Guards went back to their districts, and the spectators went home. Everyone had one thought: "The power has been seized, but what will happen next?"

(5) In his memoirs Alfred Knox, the British Military Attaché in Petrograd, reported that he met Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko when he helped free the Women's Battalion from the Bolsheviks.

When I returned to the British Embassy I found Lady Georgina in great excitement. Two officer instructors of the Women's Battalion had come with a terrible story to the effect that the 137 women taken in the Winter Palace had been beaten and tortured, and were now being outraged in the Grenadersky barracks.

I borrowed the Ambassador's car and drove to the Bolshevik headquarters at the Smolny Institute. This big building, formerly a school for the daughters of the nobility, is now thick with the dirt of revolution. Sentries and others tried to put me off, but I at length penetrated to the third floor, where I saw the Secretary of the Military-Revolutionary Committee (Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko) and demanded that the women should be set free at once. He tried to procrastinate, but I told him that if they were not liberated at once I would set the opinion of the civilized world against the Bolsheviks.

Antonov-Ovseenko tried soothe me and begged me to talk French instead of Russian, as the waiting-room was crowded and we were attracting attention. He himself talked excellent French and was evidently a man of education and culture. Finally, after two visits to the adjoining room, where he said the Council was sitting, he came back to say that the order for the release would be signed at once.

I drove with the officers to the Grenadersky barracks and went to see the Regimental Committee. The commissar, a repulsive individual of Semitic type, refused to release the women without a written order, on the ground that "they had resisted to the last at the Palace, fighting desperately with bombs and revolvers."

The Bolsheviks in this instance were as good as their word. The order arrived at the regiment soon after my departure, and the women were escorted by a large guard to the Finland Station, where they left at 9 p.m. for Levashovo, their battalion headquarters. As far as could be ascertained, though they had been beaten and insulted in every way in the Pavlovsky barracks and on their way to the Grenadersky Regiment, they were not actually hurt in the barracks of the latter. They were, however, only separated from the men's quarter by a barrier extemporized from beds, and blackguards among the soldiery had shouted threats that had made them tremble for the fate that the night might bring.

(6) Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, General Consul of the Soviet Union in Barcelona , top secret document sent to NKVD (14th October, 1936)

The relationship between our people (the Communists) and the anarcho-syndicalists is becoming ever more strained. Every day, delegates and individual comrades appear before the CC of the Unified Socialist Party with statements about the excesses of the anarchists. In places it has come to armed clashes. Not long ago in a settlement of Huesca near Barbastro twenty-five members of the UGT were killed by the anarchists in a surprise attack provoked by unknown reasons. In Molins de Rei, workers in a textile factory stopped work, protesting against arbitrary dismissals. Their delegation to Barcelona was driven out of the train, but all the same fifty workers forced their way to Barcelona with complaints for the central government, but now they are afraid to return, anticipating the anarchists' revenge. In Pueblo Nuevo near Barcelona, the anarchists have placed an armed man at the doors of each of the food stores, and if you do not have a food coupon from the CNT, then you cannot buy anything. The entire population of this small town is highly excited. They are shooting up to fifty people a day in Barcelona. (Miravitlles told me that they were not shooting more than four a day).

Relations with the Union of Transport Workers are strained. At the beginning of 1934 there was a protracted strike by the transport workers. The government and the "Esquerra" smashed the strike. In July of this year, on the pretext of revenge against the scabs, the CNT killed more than eighty men, UGT members, but not one Communist among them. They killed not only actual scabs but also honest revolutionaries. At the head of the union is Comvin, who has been to the USSR, but on his return he came out against us. Both he and, especially, the other leader of the union - Cargo - appear to be provocateurs. The CNT, because of competition with the hugely growing UGT, are recruiting members without any verification. They have taken especially many lumpen from the port area of Barrio Chino.

They have offered our people two posts in the new government - Council of Labour and the Council of Municipal Work - but it is impossible for the Council of Labour to institute control over the factories and mills without clashing sharply with the CNT, and as for municipal services, one must clash with the Union of Transport Workers, which is in the hands of the CNT. Fabregas, the councillor for the economy, is a "highly doubtful sort." Before he joined the Esquerra, he was in the Accion Popular; he left the Esquerra for the CNT and now is playing an obviously provocative role, attempting to "deepen the revolution" by any means. The metallurgical syndicate just began to put forward the slogan "family wages." The first "producer in the family" received 100 percent wages, for example seventy pesetas a week, the sec- ond member of the family 50 percent, the third 25 percent, the fourth, and so on, up to 10 percent. Children less than sixteen years old only 10 percent each, This system of wages is even worse than egalitarianism. It kills both production and the family.

In Madrid there are up to fifty thousand construction workers. Caballero refused to mobilize all of them for building fortifications around Madrid ("and what will they eat") and gave a total of a thousand men for building the fortifications. In Estremadura our Comrade Deputy Cordon is fighting heroically. He could arm five thousand peasants but he has a detachment of only four thousand men total. Caballero under great pressure agreed to give Cordon two hundred rifles, as well. Meanwhile, from Estremadura, Franco could easily advance into the rear, toward Madrid. Caballero implemented an absolutely absurd compensation for the militia - ten pesetas a day, besides food and housing. Farm labourers in Spain earn a total of two pesetas a day and, feeling very good about the militia salary in the rear, do not want to go to the front. With that, egalitarianism was introduced. Only officer specialists receive a higher salary. A proposal made to Caballero to pay soldiers at the rear five pesetas and only soldiers at the front ten pesetas was turned down. Caballero is now disposed to put into effect the institution of political commissars, but in actual fact it is not being done. In fact, the political commissars introduced into the Fifth Regiment have been turned into commanders, for there are none of the latter. Caballero also supports the departure of the government from Madrid. After the capture of Toledo, this question was almost decided, but the anarchists were categorically against it, and our people proposed that the question be withdrawn as inopportune. Caballero stood up for the removal of the government to Cartagena. They proposed sounding out the possibility of basing the government in Barcelona. Two ministers - Prieto and Jimenez de Asua - left for talks with the Barcelona government. The Barcelona government agreed to give refuge to the central government. Caballero is sincere but is a prisoner to syndicalist habits and takes the statutes of the trade unions too literally.

The UGT is now the strongest organization in Catalonia: it has no fewer than half the metallurgical workers and almost all the textile workers, municipal workers, service employees, bank employees. There are abundant links to the peasantry. But the CNT has much better cadres and has many weapons, which were seized in the first days (the anarchists sent to the front fewer than 60 percent of the thirty thousand rifles and three hundred machine guns that they seized).

(7) Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, General Consul of the Soviet Union in Barcelona , top secret document sent to NKVD (18th October, 1936)

My conversations with Garcia Oliver and with several other CNT members, and their latest speeches, attest to the fact that the leaders of the CNT have an honest and serious wish to concentrate all forces in a strengthened united front and on the development of military action against the fascists. I must note that the PSUC is not free from certain instances that hamper the "consolidation of a united front": in particular, although the Liaison Commission has just been set up, the party organ Treball suddenly published an invitation to the CNT and the FAI that, since the experience with the Liaison Commission had gone so well, the UGT and the PSUC had suggested that the CNT and the FAI create even more unity in the form of an action commission. This kind of suggestion was taken by leaders of the FAI as simply a tactical maneuver. Comrade Valdes and Comrade Sese did not hide from me that the just-mentioned suggestion was meant to "talk to the masses of the CNT over the heads of their leaders." The same sort of note was sounded at the appearance of Comrade Comorera at the PSUC and UGT demonstration on 18 October - on the one hand, a call for protecting and developing the united front and, on the other, boasting about the UGT's having a majority among the working class in Catalonia, accusing the CNT and the FAI of carrying out a forced collectivization of the peasants, of hiding weapons, and even of murdering "our comrades."

The PSUC leaders-designate agreed with me that such tactics were completely wrong and expressed their intention to change them. I propose that we get together in the near future with a limited number of representatives of the CNT and the FAI to work out a concrete program for our next action.

In the near future, the PSUC intends to bring forward the question on reorganizing the management of military industry. At this point the Committee on Military Industry works under the chairmanship of Tarradellas, but the

main role in the committee is played by Vallejos (from the FAI). The PSUC proposes to put together leadership from representatives from all of the organizations, to group the factories by specialty, and to place at the head of each group a commissar, who would answer to the government.

The evaluation by Garcia Oliver and other CNT members of the Madrid government seems well founded to me. Caballero's attitude toward the question of attracting the CNT into that or any other form of government betrays his obstinate incomprehension of that question's importance. Without the participation of the CNT, it will not, of course, be possible to create the appropriate enthusiasm and discipline in the people's militia/Republican militia.

The information concerning the intentions of the Madrid government for a timely evacuation from Madrid was confirmed. This widely disseminated information undermines confidence in the central government to an extraordinary degree and paralyzes the defense of Madrid.

(8) Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, General Consul of the Soviet Union in Barcelona , top secret document sent to NKVD (November, 1936)

The dispatch of aid to Madrid is proceeding with difficulty. The question about it was put before the military adviser on 5 November. The adviser thought it possible to remove the entire Durruti detachment from the front. This unit, along with the Karl Marx Division, is considered to have the greatest fighting value. To put Durruti out of action, a statement was issued by the commander of the Karl Marx Division, inspired by us, about sending this division to Madrid (it was difficult to take the division out of battle, and, besides, the PSUC did not want to remove it from the Catalan front for political reasons). However, Durruti refused point-blank to carry out the order for the entire detachment, or part of it, to set out for Madrid. Immediately, it was agreed with President Companys and the military adviser to secure the dispatch of the mixed Catalan column (from detachments of various parties).

A meeting of the commanders with the detachments on the Aragon front was called for 6 November, with our participation. After a short report about the situation near Madrid, the commander of the Karl Marx Division declared that his division was ready to be sent to Madrid. Durruti was up in arms against sending reinforcements to Madrid, sharply attacked the Madrid government, "which was preparing for defeat," called Madrid's situation hopeless, and concluded that Madrid had a purely political significance - and not a strategic one. This kind of attitude on the part of Durruti, who enjoys exceptional influence over all of anarcho syndicalist Catalonia that is at the front, must be smashed at all costs. It was necessary to interfere in a firm way. And Durruti gave in, declaring that he could give Madrid a thousand select fighters. After a passionate speech by the anarchist Santillan, he agreed to give two thousand and immediately issued an order that his neighbour on the front Ortiz give another two thousand, Ascaso another thousand, and the Karl Marx division a thousand. Durruti was silent about the Left Republicans, although the chief of their detachment declared that he could give a battalion. In all, sixty-eight hundred bayonets are shaping up for dispatch no later than 8 November. Durruti then and there put his deputy at the head of the mixed detachment (Durruti agreed to form it as a "Catalan division"). He declared that he would personally be with the detachment until the appointment (of the new head). But Durruti unexpectedly pulled a stunt, holding up the dispatch. Learning about the "discovery" of a kind of supplementary weapon (Winchester), instead of sending the units from the front on a direct route to Madrid, he sent these units unarmed into Barcelona, leaving their weapons (Mauser system) at their own place on the front and instead calling up reserves (without weapons) from Barcelona. His anarchist neighbours did the same thing. Thus Durruti got his own way - the Aragon front was not weakened.

About five thousand disarmed frontline soldiers were gathered in Barcelona, and Durruti raised the question about immediately arming them at the expense of the units of the Barcelona gendarmerie and police. Through this, Durruti would achieve a continual striving by the CNT and the FAI to undermine the armed support of the present government in Barcelona. Since the weapons seized from the Garde d'Assaut and Garde Nationale (about twenty-five hundred rifles) were still not enough, it was proposed to get them from the "rear soldiers," and instead of weapons of a different sort, the Garde d'Assaut and Garde Nationale would also, according to Durruti, receive Winchesters in place of Mausers. Here the government's decree on the handing over of weapons by the soldiers at the rear has already been frustrated.