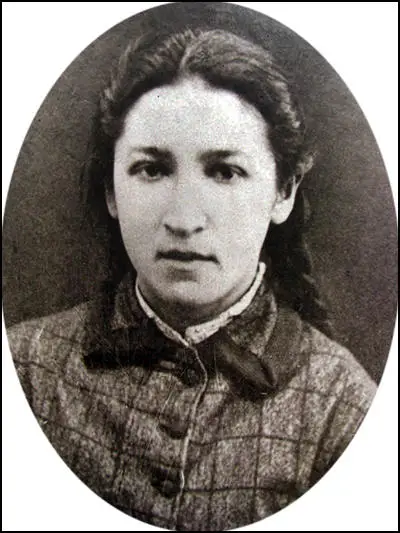

Vera Zasulich

Vera Zasulich was born into a poor family living in Mikhaylovka, Russia, in 1849. Her father died when she was three years old and as her mother was unable to cope, she sent Vera to live with wealthy relatives in Balakovo.

When Zasulich finished her schooling she moved to St. Petersburg and found work as a clerk. She became involved in radical politics and met Sergi Nechayev, the co-author with Mikhail Bakunin of Catechism of a Revolutionist. "Nechayev began to tell me his plans for carrying out a revolution in Russia in the near future.... I could imagine no greater pleasure than serving the revolution. I had dared only to dream of it, and yet now he was saying that he wanted to recruit me, that otherwise he wouldn't have thought of saying anything."

Lev Deich got to know her during this period: "Because of her intellectual development, and particularly she was so well read, Vera Zasulich was more advanced than the other members of the circle... Anyone could see that she was a remarkable young woman. You were struck by her behavior, particularly by the extraordinary sincerity and unaffectedness of her relations with others."

Zasulich joined a weaving collective and became active in the movement to educate workers, conducting literacy classes for them in the evenings. In 1876 Zasulich found work as a typesetter for an illegal printing press. A member of the Land and Liberty group, when Zasulich heard that one of her fellow comrades, Tatiana Lebedeva, had witnessed one of the prisoners, Alexei Bogoliubov, take a terrible beating at the hands of Dmitry Trepov, the Governor General of St. Petersburg, she decided she must take revenge.

According to Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976): "By July 1877 the atmosphere in the prison had already reached boiling-point when Trepov, Governor-General of St Petersburg, made his tour of inspection. The political detainees watched from their cell windows as Trepov, who was in a particularly vicious mood that day, examined prisoners in the yard below. Suddenly, over-reacting to some imagined misdemeanour of Bogolyubov's, he ordered him to be flogged savagely. Bogolyubov went insane as a result of the beating... That night the prison resounded to the shouts of the detainees. In the women's section Tatiana Lebedeva, whose health had been seriously undermined by prison conditions, vociferously urged her friends to shout out their support for Bogolyubov. Prison officers made savage reprisals, and many women were dragged out of their cells by their hair and flogged."

When Zasulich heard the news she went to the local prison determined to assassinate Trepov. She later recalled that she went to Trepov's office with a revolver hidden under her cloak: "The revolver was in my hand. I pressed the trigger - a misfire. My heart missed a beat. Again I pressed. A shot, cries. Now they'll start beating me. This was next in the sequence of events I had thought through so many times. I threw down the revolver - this also had been decided beforehand; otherwise, in the scuffle, it might go off by itself. I stood and waited. Suddenly everybody around me began moving, the petitioners scattered, police officers threw themselves at me, and I was seized from both sides."

Zasulich was arrested and charged with attempted murder. During the trial the defence produced evidence of such abuses by the police, and Zasulich conducted herself with such dignity, that the jury acquitted her. When the police tried to re-arrest her outside the court, the crowd intervened and allowed her to escape. Zasulich commented: "I could not understand this feeling then, but I have understood it since. Had I been convicted, I should have been prevented by main force from doing anything, and I should have been tranquil, and the thought of having done all I was able for the cause would have been a consolation to me."

Sergei Kravchinsky argued that Vera Zasulich was a new kind of hero: "On the horizon appeared the outlines of a sombre figure, illuminated by some kind of hellish flame, a figure with chin raised proudly in the air, and a gaze that breathed provocation and vengeance. Passing through the frightened crowds, the revolutionary enters with proud step on to the arena of history. He is wonderful, awe-inspiring and irresistible, for he unites the two most lofty forms of human grandeur, the martyr and the hero."

Vera Zasulich was forced into hiding but remained active in politics and joined the Black Repartition group as by this time she had rejected the use of violence to gain a democratic system. Zasulich was a strong supporter of George Plekhanov. Zasulich, like Plekhanov, was highly critical of the terror campaign being carried out by the People's Will.

In 1883 Zasulich joined with George Plekhanov and Paul Axelrod to form the Liberation of Labour, the first Russian Marxist group. Later she moved to Switzerland where she became active in the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) and served on the editorial board of Iskra.

Zasulich became known for her propaganda work amongst industrial workers. In an article in Justice in 1897 she argued: "The Russian Labour movement is the youngest and the weakest in Europe. Only a year ago, and its very existence was denied by the Russian Government, the whole Russian Press, and all Russian society. It was only a handful of Social-Democrats who patiently laboured to free this movement, long since born, from its swaddling clothes. And, lo! at the present moment the German Government is hardly more afraid of the great German Social-Democratic Party than is the Russian Government of our young movement. At the first rumour of the last strike, during the beginning of January, and which affected over 5,000 cotton-spinners and weavers, extraordinary Cabinet Councils were called, and sat for several days. It is not easy to say what these Cabinet meetings decided."

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Jules Martov, two of SDLP's leaders. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists.

Jules Martov based his ideas on the socialist parties that existed in other European countries such as the British Labour Party. Lenin argued that the situation was different in Russia as it was illegal to form socialist political parties under the Tsar's autocratic government. At the end of the debate Martov won the vote 28-23 . Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks.

Gregory Zinoviev, Anatoli Lunacharsky, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Lashevich, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Mikhail Frunze, Alexei Rykov, Yakov Sverdlov, Lev Kamenev, Maxim Litvinov, Vladimir Antonov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Gregory Ordzhonikidze and Alexander Bogdanov joined the Bolsheviks. Whereas Zasulich, George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Leon Trotsky, Lev Deich, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Noi Zhordania and Fedor Dan supported Jules Martov.

She returned to Russia during the 1905 Revolution but after its failure ceased to be active in politics. During the First World War Zasulich supported the war effort and opposed the Bolshevik Revolution.

Vera Zasulich died in 1919.

Primary Sources

(1) When Vera Zasulich met Sergi Nechayev he immediately tried to recruit her into the revolutionary movement.

Nechayev began to tell me his plans for carrying out a revolution in Russia in the near future. I felt terrible: it was really painful for me to say "That's unlikely," "I don't know about that". I could see that he was very serious, that this was no idle chatter about revolution. He could and would act - wasn't he the ringleader of the students?

I could imagine no greater pleasure than serving the revolution. I had dared only to dream of it, and yet now he was saying that he wanted to recruit me, that otherwise he wouldn't have thought of saying anything. And what did I know of "the people"? I knew only the house serfs of Biakolovo and the members of my weaving collective, while he was himself a worker by birth.

(2) In 1876 Vera Zasulich attempted to kill the police chief, General Trepov after he had given the order to beat fellow revolutionary, Alexei Bogoliubov.

Now Trepov and his entourage were looking at me, their hands occupied by papers and things, and I decided to do it earlier than I had planned - to do it when Trepov stopped opposite my neighbour, before reaching me.

And suddenly there was no neighbour ahead of me - I was first.

"What do you want?"

"A certificate of conduct."

He jotted down something with a pencil and turned to my neighbour.

The revolver was in my hand. I pressed the trigger - a misfire.

My heart missed a beat. Again I pressed. A shot, cries. Now they'll start beating me. This was next in the sequence of events I had thought through so many times.

I threw down the revolver - this also had been decided beforehand; otherwise, in the scuffle, it might go off by itself. I stood and waited.

Suddenly everybody around me began moving, the petitioners scattered, police officers threw themselves at me, and I was seized from both sides.

(3) Olga Liubatovich was in Geneva with Vera Zasulich when news arrived that Alexander Soloviev had attempted to kill Alexander II.

In the spring of 1879, the unexpected news of Alexander Soloviev's attempt on the life of the Tsar threw Geneva's Russian colony into turmoil. Vera Zasulich hid away for three days in deep depression: Soloviev's deed obviously reflected a trend toward direct, active struggle against the government, a trend of which Zasulich disapproved. It seemed to me that her nerves were so strongly affected by violent actions like Soloviev's because she consciously (and perhaps unconsciously, as well) regarded her own deed as the first step in this direction.

(4) Vera Zasulich, Justice (30th January, 1897)

On January 2 a strike broke out at the two factories of Mr. Maxwell in St. Petersburg, in which 5,000 men are already involved, but which it may be expected will soon spread over all other factories which took part in the strike of last summer. The chief demand is for a shorter working day. Our English comrades may remember the former gigantic strike, which began in the middle of June and gradually died out by the middle of July. During all the time the strike was going on we have been left almost without information from our comrades - a fact which will be intelligible enough to anyone acquainted with the conditions of strikes in Russia. The position of the leaders at that time is very dangerous, inasmuch as every moment they may be arrested and imprisoned, the least written line on the strike found with them being in the eyes of the police an incontrovertible proof of their guilt. The very dispatch of such lines is a highly risky affair. Besides, during this time all the thoughts are absorbed in finding means and ways of how to get funds for the next day’s distribution; and, though the help and sympathy of the foreign brethren is highly appreciated and important, still as this help and sympathy cannot arrive immediately the care of them necessarily steps into the background in these hours of anguish and struggle and danger. Since, however, the end of this strike we received the full particulars of the whole affair, and some of them may throw a flood of light on this new strike.

At the very beginning of the last summer’s strike the Chief of the St. Petersburg Police, Major-General Cleggels, an officer of very great importance, called together the employees from various factories, and, not listening properly to their demand, said that he is fully aware of the cruel exploitation they have to undergo at the hands of their masters, and expostulated with them to return to their work, promising to investigate and satisfy their grievances. In the very heat of the strike, on June 10 the same Cleggels issued a proclamation to the workers stating that as soon as they returned to work all their demands which can be satisfied without invoking the legislature should be so satisfied immediately, and the rest should be referred to the higher powers. Lastly, on June 15, when hunger made itself felt very keenly, the Russian Prime Minister, the Minister of Finances; M. Witte, issued on his part a proclamation written in a quasi-popular style and posted on the walls and given away amongst the strikers. In this proclamation the great magician who contrives to make the Budget show big surpluses instead of deficits, announces to the men that “during the strike no demand, not even if just, could be satisfied,” whilst, if work is required, their demand “will be fully gone into and settled amicably.” And, indeed, after the strike was over, some abuses which were already prohibited by the factory inspector long ago - such as monthly payments instead of bi-monthly, cleaning of machinery in the hours of rest, and others - were gradually abolished.

(5) Vera Zasulich, Justice (1st May, 1897)

The Russian Labour movement is the youngest and the weakest in Europe. Only a year ago, and its very existence was denied by the Russian Government, the whole Russian Press, and all Russian society. It was only a handful of Social-Democrats who patiently laboured to free this movement, long since born, from its swaddling clothes. And, lo! at the present moment the German Government is hardly more afraid of the great German Social-Democratic Party than is the Russian Government of our young movement. At the first rumour of the last strike, during the beginning of January, and which affected over 5,000 cotton-spinners and weavers, extraordinary Cabinet Councils were called, and sat for several days. It is not easy to say what these Cabinet meetings decided. The factory inspectors received certain instructions in a circular; then the decision there notified was reversed, the circular withdrawn, and ‘another circular issued — the diametrical opposite of the first one. It reminded cane of the French Cabinet Councils during the February days of 1848. And all this because of a perfectly quiet, well-conducted, and orderly strike. Nevertheless, there is ground enough for anxiety on the part of the Ministers. The Russian Labour movement is not at the prevent moment in the least antagonistic to the industrial interests of the country. On the contrary, what the workers demand — a shorter working day and higher wages — would compel the employers to cease the senseless competition now raging, a competition based upon a fourteen hours’ day, and deductions from wages amounting on an average to 30s a month, and would force them to compete with each other by means of improved machinery, better methods of production, and a higher quality of goods — all of which world further the growth of capitalism. But the Labour movement is antagonistic to autocracy, however modest its immediate demands.

Try and, imagine what the state of things was during the great strike last summer. For the last few years our press has been forbidden to mention labour disputes, and so it came to pass that the deadlock in the St. Petersburg cotton industry, which the whole press of Europe was discussing, was never so much as referred to in Russian newspapers and periodicals! To the centre of the city itself the fact that there was a strike going on in its suburbs was only made known by people who happened to have been in the suburbs. In Moscow it was a week after the movement had begun that vague rumours spread from mouth to mouth that something was going on, only the Moscow League” receiving “detailed information. In other towns, where there was no well-defined labour organisation, the news of the great strike probably arrived long after it was over. It is not likely that this prohibition to speak of the strike was made with a view to sparing the feelings of our bourgeoisie, or our nobility, or our clergy; it was directed against the working-class. And yet it was in the working-class quarters that the leaflets of the “League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Classes” had an immense circulation, not only among those directly involved, but among the workers in other industries. The strike, which did not exist for the “legal” press, was the chief topic of discussion in the persecuted but free press of the proletariat. And the leaflets issued by the League certainly had more influences than any ordinary newspapers could have had, especially as the strike was known to be forbidden fruit. Then the workingmen began to like these leaflets, they had confidence in them; the whole working population began to be familiar with there those who could reading out, the contents to the illiterate. And so the strike became a matter of profound interest not only to the spinners and wavers themselves but to the entire proletariat of St. Petersburg and later on of Moscow.