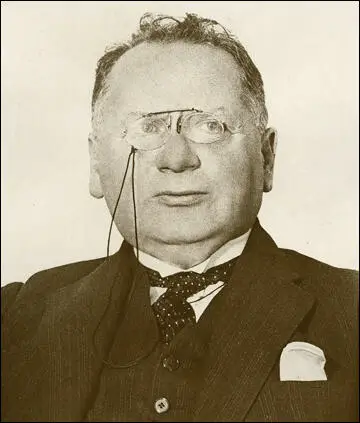

Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Litvinov was born into a prosperous Jewish family in Russia in 1876. He left school at seventeen and joined the Russian Army. After leaving the army in 1900 Litvinov joined the illegal Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) but was soon arrested by Okhrana. After 18 months in captivity, Litvinov escaped and made his way to Switzerland. He joined the SDLP in exile and joined the editorial board of its journal, Iskra.

Litvinov returned to Russia in 1903 and after the 1905 Revolution became editor of the SDLP's first legal newspaper, Novaya Zhizn (New Life). When the Russian government began arresting Bolsheviks in 1906, Litvinov left the country and spent the next ten years living in London where he was active in the International Socialist Bureau.

After the October Revolution, Litvinov was appointed by Vladimir Lenin as the Soviet Government's representative in Britain. However, in 1918, Litvinov was arrested by the British Government and held until exchanged for Bruce Lockhart, the British diplomat who had been imprisoned in Russia. As he explained in his autobiography: "After the October Revolution I was appointed the first ambassador to England. Ten months later I was arrested as a hostage for Lockhart and we were later exchanged. I travelled to Sweden and Denmark for negotiations with the bourgeois governments and concluded a series of agreements on the exchange of prisoners of war. I achieved the removal of the British blockade, made the first trade deals in Europe and dispatched the first cargoes after the blockade had been lifted."

In the summer of 1921, Carr Van Anda, the managing director of the New York Times, sent Walter Duranty to report on the new policy of war communism in Russia. At first, Maxim Litvinov, refused to let him into the country because of his previous hostile stories about the government. George Seldes, of the Chicago Tribune, said that nobody expected Duranty to get a visa. "Litvinov singled Walter Duranty out - he didn't want to admit him."

However, Litvinov changed his mind and did issue him with a visa after he read an article by Duranty that appeared in the New York Times on 13th August, 1921: "Lenin has thrown communism overboard. His signature appears in the official press of Moscow in August 9, abandoning State ownership, with the exception of a definite number of great industries of national importance - such as were controlled by the State in France, England and Germany during the war - and re-establishing payment by individuals for railroads, postal and other public services." However, like the other Western journalists, he was still not allowed into the famine areas.

Litvinov also had problems with Floyd Gibbons, another American journalist who wanted to report the famine. David Randall, the author of The Great Reporters (2005) has argued: "Some time that summer, word began to leak out of the new Soviet state that people in their millions were starving in the Volga region. Checking these rumours was easier said than done. The Bolshevik government allowed no Western journalists to be based in Moscow, and coverage of the country was in the hands of reporters who hung around Riga's restaurants talking to emigres, White Russians and other unreliable witnesses.... The Soviets were not letting them in; they wanted US food aid, but were afraid the full extent of the tragedy would be revealed. After the Tribune's men kicked their heels for a week, Chicago cabled Floyd Gibbons to go to Riga himself..... The rest of the press had dutifully filled out an application form for entry. Not Gibbons. Instead he told his German pilot to keep his plane primed for take-off, and let it be known around the bars that lie was thinking of making an illicit flight into Russia. Sure enough, informants picked up the story, and next day Gibbons was summoned to see Litvinov, the Soviet ambassador. The meeting pitted the two wiliest brains in Riga against each other. Litvinov said he knew about Gibbons's plane, and warned him that if he tried to fly across the border he would be shot down. Gibbons countered by pointing out that the Russian border ran from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and anti-aircraft guns covered a mere traction of it. Litvinov then threatened to have Gibbons arrested, to which the reporter replied that the Soviets had just released all their US prisoners in order to secure food aid and were not likely to start incarcerating Americans again. Checkmate. That night, while the rest of the press fumed in Riga, Gibbons boarded a train for Moscow with Litvinov, and, after a few days in the capital, was on another train bound for the Volga."

Walter Duranty said that Floyd Gibbons "fully deserved his success because he had accomplished the feat of bluffing the redoubtable Litvinov stone-cold... a noble piece of work." Over the next few days Gibbons was the only reporter to document the horrifying prospect of the deaths of as many as fifteen million people from starvation.

Litvinov was then employed as the Soviet Government's roaming ambassador. It was largely through his efforts that Britain agreed to end its economic blockade of the Soviet Union. Litvinov also negotiated several trade agreements with European countries. In 1930 Joseph Stalin appointed Litvinov as Commissar of Foreign Affairs. A firm believer in collective security, Litvinov worked very hard to form a closer relationships with France and Britain.

With the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt to the presidency, the diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union became a strong possibility. In November 1933 the Soviets were invited to send a representative to Washington to begin negotiations. Walter Duranty, an American journalist based in Moscow, obtained permission to accompany Litvinov on his historic journey across the Atlantic. When they reached New York Duranty quoted Litvinov as describing the skyline as "looming like castle giants in the hazy morning".

As Jean Edward Smith pointed out in FDR (2007): "The ostensible outstanding issues involved freedom of religion for Americans in Russia and the continued agitation for world revolution mounted by the Comintern. The real sticking point was restitution of American property seized by the Soviet government in its nationalization decree of 1919. Roosevelt and Litvinov compromised. The agreement is known as the Litvinov Assignment. The Soviet government assigned to the United States its claim to all Russian property in the United States that antedated the Revolution. The United States agreed to seize the property on behalf of the Soviet Union, thus giving effect to the Soviet nationalization decree, and use the proceeds to pay the claims of Americans whose property in Russia had been confiscated.... Shortly after midnight on the morning of November 17, FDR and Litvinov signed the documents restoring diplomatic relations." Walter Duranty wrote in the New York Times on 18th November 1933 that he had just witnessed "the ten days that steadied the world".

Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister was also involved in negotiations with Litinov: "I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears. Moreover, she is both hated and suspected by many of the smaller States, notably by Poland, Rumania and Finland."

Litvinov's Jewish origins created problems for Joseph Stalin during his negotiations with Nazi Germany in 1939 and was replaced by Vyacheslav Molotov just before the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. After the outbreak of war with Germany, Stalin appointed Litvinov as Deputy Commissar of Foreign Affairs. He also served as Ambassador to the United States (1941-43).

Maxim Litvinov died in 1951.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1924 Maxim Litvinov wrote an autobiography for The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution.

After the October Revolution I was appointed the first ambassador to England. Ten months later I was arrested as a hostage for Lockhart and we were later exchanged. I travelled to Sweden and Denmark for negotiations with the bourgeois governments and concluded a series of agreements on the exchange of prisoners of war. I achieved the removal of the British blockade, made the first trade deals in Europe and dispatched the first cargoes after the blockade had been lifted.

(2) David Randall, The Great Reporters (2005)

In 1921 came his greatest triumph of all: the Russian Famine. Some time that summer, word began to leak out of the new Soviet state that people in their millions were starving in the Volga region. Checking these rumours was easier said than done. The Bolshevik government allowed no Western journalists to be based in Moscow, and coverage of the country was in the hands of reporters who hung around Riga's restaurants talking to emigres, White Russians and other unreliable witnesses. But as sketchy reports of a fearful famine gained momentum, so did interest in the story back home, and in mid-August Gibbons received this cable from Chicago: "Concentrate all available corrs on Russia. It is the greatest story in the world today. We must have first exclusive eye-witness report from corr on the spot." He sent two reporters, who soon joined all the other correspondents milling about Latvia waiting for permission to enter Russia. The Soviets were not letting them in; they wanted US food aid, but were afraid the full extent of the tragedy would be revealed. After the Tribune's men kicked their heels for a week, Chicago cabled Gibbons to go to Riga himself. Two days later he arrived - and was promptly arrested for landing without a visa. A bribe took care of that, and, once in town, he took the advice of colleague George Seldes and hatched a plan that might just get him into Russia. The rest of the press had dutifully filled out an application form for entry. Not Gibbons. Instead he told his German pilot to keep his plane primed for take-off, and let it be known around the bars that lie was thinking of making an illicit flight into Russia. Sure enough, informants picked up the story, and next day Gibbons was summoned to see Litvinov, the Soviet ambassador.

The meeting pitted the two wiliest brains in Riga against each other. Litvinov said he knew about Gibbons's plane, and warned him that if he tried to fly across the border he would be shot down. Gibbons countered by pointing out that the Russian border ran from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and anti-aircraft guns covered a mere traction of it. Litvinov then threatened to have Gibbons arrested, to which the reporter replied that the Soviets had just released all their US prisoners in order to secure food aid and were not likely to start incarcerating Americans again. Checkmate. That night, while the rest of the press fumed in Riga, Gibbons boarded a train for Moscow with Litvinov, and, after a few days in the capital, was on another train bound for the Volga. The ride took 40 hours, but the scene that greeted him in Samara was of such medieval degradation, it might as well have been a journey back through the centuries. So awful was the stench of death as he stepped from his carriage, and so high the risk of cholera and typhus, that he did his reporting with a towel soaked in disinfectant held to his face.

(3) Neville Chamberlain, letter to a friend (26th March, 1939)

I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears. Moreover, she is both hated and suspected by many of the smaller States, notably by Poland, Rumania and Finland.

(4) On 16th April, 1939, the Soviet Union suggested a three-power military alliance with Great Britain and France. In a speech on 4th May, Winston Churchill urged the government to accept the offer.

Ten or twelve days have already passed since the Russian offer was made. The British people, who have now, at the sacrifice of honoured, ingrained custom, accepted the principle of compulsory military service, have a right, in conjunction with the French Republic, to call upon Poland not to place obstacles in the way of a common cause. Not only must the full co-operation of Russia be accepted, but the three Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, must also be brought into association. To these three countries of warlike peoples, possessing together armies totalling perhaps twenty divisions of virile troops, a friendly Russia supplying munitions and other aid is essential.

There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge.