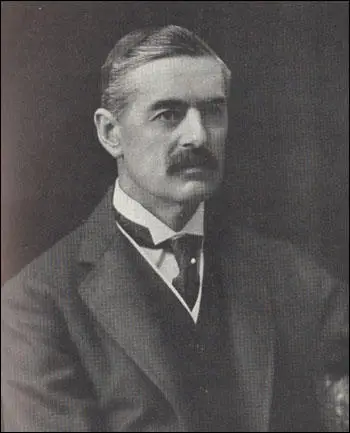

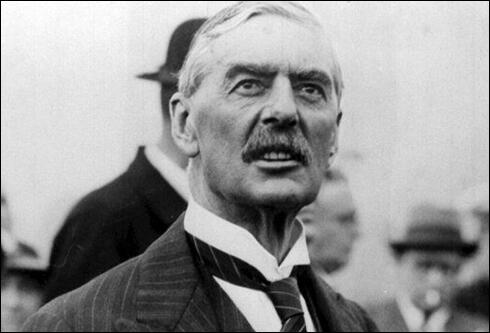

Neville Chamberlain

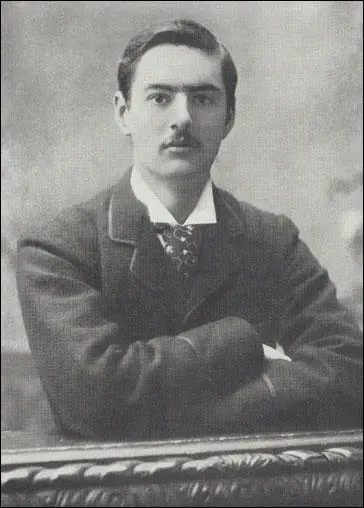

Neville Chamberlain, the only son of Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) and his second wife Florence Kenrick (1847–1875) on 18th March, 1869 at Edgbaston, Birmingham. His father's first wife, Harriet Kenrick, had died while giving birth to Neville's elder half-brother, Austen Chamberlain, in 1863, and he married her cousin, in 1868. (1)

Chamberlain grew up in an atmosphere of fervent Unitarianism, within a happy family surrounded by cousins. However, his mother died in 1875 after the birth of her fourth child. "This unquestionably left its mark on Joseph Chamberlain and imposed a certain strain on his relations with his children." (2)

Joseph had two children by his first wife: Beatrice and Austin and four children by his second wife: Neville, Ida, Hilda and Ethel. Joseph became mayor of Birmingham in 1873 and the following year he sold the family business for £120,000. He invested heavily in South America and lived off the interest. A member of the Liberal Party he was elected to the House of Commons to represent Birmingham on 17th June, 1876. (3)

Neville Chamberlain hated his time at Rugby School where he was badly bullied by a boy whom Austen had beaten when he was a school prefect. As a result he became somewhat shy and withdrawn and was a reluctant participant in school debates. When asked why this was he referred to the unpleasant atmosphere in the house when his father was preparing to make an important speech. It has been suggested that this probably reflected his "adolescent resentment against a dominant father". (4)

At the end of 1886 Neville left school, but there was no question of his following Austen to Cambridge University. Austen had been sent there by his father and thence on an extensive tour of Europe as preparation for a career in politics. Joseph Chamberlain admitted that Neville was "the really clever one" but thought it would be better to send him to study metallurgy and engineering at Mason Science College. (5)

Andrew J. Crozier pointed out: "Although but a university education was deemed an unnecessary expense for a career in business. In this Joseph Chamberlain, although unintentionally, did Neville a great disservice. A university education would in all probability have made him a better integrated, more self-confident, and poised personality, with a capacity to project his inner warmth beyond the confines of the family and intimate friends and an ability to appreciate that there were points of view as intellectually sound as his own." (6)

In 1890 there was a massive slump in the Argentinean economy, which threatened the Chamberlain family with financial meltdown. Joseph Chamberlain, who at that time was the Colonial Secretary, had a conversation with Ambrose Shea, the Governor of the Bahamas, persuaded him that he could recoup his losses by growing sisal, a plant with stiff purple leaves from which high-quality hemp could be made. Joseph sent Neville to Nassau to investigate the prospect of what promised to be a 30 per cent return on his investment. (7)

In May 1891, Neville was given the responsibility of setting up the venture on the remote Bahamian island of Andros. The following month he was able to write: "It is with the deepest satisfaction that I am able to inform you today that the first part of my business is satisfactorily concluded. I have pitched on a tract of land in Andros Island and made an agreement with the governor... on the whole it is of excellent quality, very level, and unbroken... I am confident that I have secured the best site available in the Bahamas." (8)

It was a lonely existence.with his nearest neighbour, was only three miles away but it was a difficult journey that would take up most of the day. Knowles, his white overseer was poorly educated and was not a good "mental companion". He did enjoy talking to his wife but she died and he wrote: "What little social life I had is gone absolutely, and I see myself condemned to a life of total solitude, mentally if not physically." He therefore had to depend on a chance visit from a passing sponge merchant, or the mission priest from Fresh Creek, twenty miles to the south. His main excitement was the letters he received every fortnight. (9)

Joseph Chamberlain encouraged his son to stay on this remote island: "I feel that this experience, whatever its ultimate result on our fortunes, will have had a beneficial and formative effect on your character. At times, in spite of all the hardships and annoyances you have to bear, I am inclined to envy you the opportunity you are having to show your manhood. Remember, however, now and always that I value your health more than anything, and that you must not run any unnecessary risks either by land or sea." (10)

Neville Chamberlain's initial optimism was misplaced. Sisal plants did not grow successfully on the island and warned his father that the venture might fail. His father replied that "you seem to contemplate as a possibility the entire abandonment of the undertaking in which I shall have invested altogether (with the liabilities I have accepted) about £50,000. This would indeed be a catastrophe." (11)