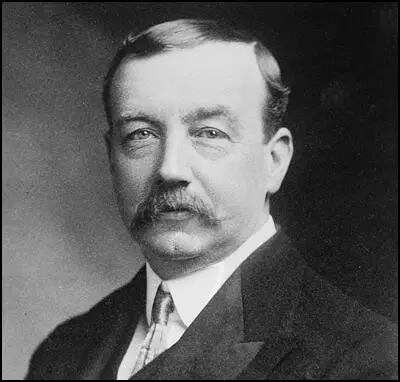

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson, the son of a cotton spinner, was born in Glasgow on 13th September, 1863. His father, suffered long periods of unemployment, and so Arthur was forced to leave school at nine years old to find work as an errand boy in a photographer's shop. Arthur's wages became even more important to the family income after the death of his father in 1874.

When Arthur's mother married Robert Heath, the family moved to Newcastle-upon-Tyne. At the age of twelve Arthur found work at the Robert Stephenson locomotive works. Despite a ten hour day, Arthur attended evening classes in an effort to improve his education.

Henderson had been brought up as a staunch Congregationalist, but in 1879 he was converted by the preacher, Rodney Smith, to Methodism. He became a lay preacher and an active member of the Temperance Society. After finishing his apprenticeship at seventeen, Arthur Henderson moved to Southampton for a year and then returned to work as a iron moulder in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Henderson became an active trade unionist and formed a reading a debating society at the Stephenson locomotive works. In 1884 Henderson lost his job and was out of work for fourteen months. Henderson used this time to continue his education and to work as a lay preacher.

In 1892 Henderson was elected as a paid organiser of the Iron Founders Union. Henderson was one of the worker representatives on the North East Conciliation Board. A strong believer in arbitration and industrial co-operation, Henderson opposed the formation of the General Federation of Trade Unions as he believed it would increase the frequency of industrial disputes.

On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain (the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society, met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. Arthur Henderson was one of the 129 delegates who decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC).

In 1903 Henderson was elected treasurer of the LRC. He was opposed by members of the Independent Labour Party who objected to the fact that Henderson was a liberal rather than a socialist. In a by-election later that year, Henderson was elected as MP for Barnard Castle. Three years later Henderson chaired the conference at which the LRC was transformed into the Labour Party. The party's first Chairman was James Keir Hardie, but he was not very good with dealing with internal rivalries within the party, and in 1908 resigned from the post and Henderson became chairman. Henderson did not have the full-support of the Labour Party and in 1910 he resigned as chairman.

Ramsay MacDonald was expected to become the new leader but recently his youngest son had died of diphtheria. Eight days later his mother also died. It was therefore decided that George Barnes should become chairman. A few months later Barnes wrote to MacDonald saying he did not want the chairmanship and was "only holding the fort". He continued, "I should say it is yours anytime".

Henderson also suggested that MacDonald should become chairman. As David Marquand, the author of Ramsay MacDonald (1977) pointed out: "It is unlikely that he did so out of a sudden access of personal affection, or even out of admiration for MacDonald's character and abilities. He wanted MacDonald as chairman, partly because he wanted to be party secretary himself and believed correctly that he would be a good one, partly because he believed - again correctly - that MacDonald was the only potential candidate capable of reconciling the ILP to the moderate line favoured by the unions.... MacDonald and Henderson differed in taste, temperament and political background, and it is doubtful if either ever liked the other. Henderson was frequently exasperated by MacDonald's moodiness, unpredictability and unwillingness to communicate; he may also have suspected, not altogether unreasonably, that MacDonald undervalued his talents and took him too much for granted. MacDonald, for his part, found Henderson unimaginative and domineering, and, in later years at any rate, was never quite sure of his support."

The 1910 General Election saw 40 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons. Two months later, on 6th February, 1911, George Barnes sent a letter to the Labour Party announcing that he intended to resign as chairman. At the next meeting of MPs, Ramsay MacDonald was elected unopposed to replace Barnes. Henderson now became secretary. According to Philip Snowden, a bargain had been struck at the party conference the previous month, whereby MacDonald was to resign the secretaryship in Henderson's favour, in return for becoming chairman."

MacDonald was totally against Britain's involvement in the First World War. His views were shared by other Labour Party leaders such as James Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. Others in the party such as Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett believed that the movement should give total support to the war effort.

On 5th August, 1914, the parliamentary party voted to support the government's request for war credits of £100,000,000. Ramsay MacDonald immediately resigned the chairmanship of the Labour Party. He wrote in his diary: "I saw it was no use remaining as the Party was divided and nothing but futility could result. The Chairmanship was impossible. The men were not working, were not pulling together, there was enough jealously to spoil good feeling. The Party was no party in reality. It was sad, but glad to get out of harness." Arthur Henderson, once again, became the leader of the party.

In May 1915, Henderson became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. Bruce Glasier commented in his diary: "This is the first instance of a member of the Labour Party joining the government. Henderson is a clever, adroit, rather limited-minded man - domineering and a bit quarrelsome - vain and ambitious. He will prove a fairly capable official front-bench man, but will hardly command the support of organised Labour." Henderson was also President of the Board of Education (May, 1915 - October, 1916) and Paymaster General (October, 1916 - August, 1917), during the First World War.

After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia, socialists in Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, United States and Italy called for a conference in a neutral country to see if the First World War could be brought to an end. Eventually, it was announced that the Stockholm Conference would take place in July 1917. Arthur Henderson was sent by David Lloyd-George to speak to Alexander Kerensky, the leader of the Provisional Government in Russia.

At a conference of the Labour Party held in London on 10th August, 1917, Henderson made a statement recommending that the Russian invitation to the Stockholm Conference should be accepted. Delegates voted 1,846,000 to 550,000 in favour of the proposal and it was decided to send Henderson and Ramsay MacDonald to the peace conference. However, under pressure from President Woodrow Wilson, the British government had changed his mind about the wisdom of the conference and refused to allow delegates to travel to Stockholm. As a result of this decision, Henderson resigned from the government.

Arthur Henderson disagreed with those politicians who believed Germany should be harshly treated after the First World War, and as a result of the nationalist fervour of the 1918 General Election, he lost his seat. He returned to the House of Commons the following year as MP for Widnes. Henderson became chief whip of the party but was defeated at the 1922 General Election.

Elected for East Newcastle at a by-election at two months later, he was defeated once again in the 1923 General Election. He returned at a by-election at Burnley in February 1924 and joined the government headed by Ramsay MacDonald as Home Secretary.

In October 1924 the MI5 intercepted a letter written by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union. The Zinoviev Letter urged British communists to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Vernon Kell, head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson head of Special Branch, told MacDonald that they were convinced that the letter was genuine.

It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government.

Following Labour's defeat in the 1924 General Election, Philip Snowden and other leading figures in the movement tried to persuade Henderson to stand against MacDonald as leader of the party. Henderson refused and once again became chief whip of the party where he tried to unite the party behind MacDonald's leadership. Henderson was also the main person responsible for Labour and the Nation, a pamphlet that attempted to clarify the political aims of the Labour Party.

After the 1929 General Election victory, Ramsay MacDonald appointed Henderson as his Foreign Secretary. In this post Henderson attempted to reduce political tensions in Europe. Diplomatic relations were re-established with the Soviet Union and Henderson gave his full support to the League of Nations by arguing for international arbitration, de-militarization and collective security.

In 1931 Philip Snowden, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, suggested that the Labour government should introduce new measures to balance the budget. This included a reduction in unemployment pay. Several ministers, including Henderson, George Lansbury and Joseph Clynes, refused to accept the cuts in benefits and resigned from office.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Jimmy Thomas, Philip Snowden and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

In October, MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Henderson lost his seat at Burnley but returned to the House of Commons at a by-election at Clay Cross in September 1933.

Over the next few years Henderson worked tirelessly for world peace. Between 1932 and 1935 he chaired the Geneva Disarmament Conference and in 1934 his work was recognised when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Arthur Henderson died in London on 20th October, 1935.

Primary Sources

(1) Arthur Henderson, speech at the Congregational Memorial Hall (February 1906)

In my opinion our policy towards the new Government will be exactly the same as it was towards the old Government. We shall give them support when it is possible, but we shall oppose them when it is necessary. Doubtless their own loyal followers will give them support ; but we have a much greater responsibility devolving upon us than this. Upon our party rests the responsibility of keeping this Government up to the scratch of its own professions, and a further responsibility of shaping their policy in harmony with public necessity. Our marvellous successes at the polls have demonstrated that the Labour forces are the greatest factor in the present political situation. The wage-earners have at last declared themselves in favour of definite, united, independent political action, and we this morning can rejoice in an electoral triumph which, having regard to all the circumstances, can be safely pronounced phenomenal. We can congratulate ourselves today that a real live independent Labour Party, having its own chairman, its own deputy-chairman, and its own whips, is now an accomplished fact in British politics.

(2) David Marquand, Ramsay MacDonald (1977)

Henderson urged MacDonald to stand for the chairmanship. It is unlikely that he did so out of a sudden access of personal affection, or even out of admiration for MacDonald's character and abilities. He wanted MacDonald as chairman, partly because he wanted to be party secretary himself and believed correctly that he would be a good one, partly because he believed - again correctly - that MacDonald was the only potential candidate capable of reconciling the ILP to the moderate line favoured by the unions.... MacDonald and Henderson differed in taste, temperament and political background, and it is doubtful if either ever liked the other. Henderson was frequently exasperated by MacDonald's moodiness, unpredictability and unwillingness to communicate; he may also have suspected, not altogether unreasonably, that MacDonald undervalued his talents and took him too much for granted. MacDonald, for his part, found Henderson unimaginative and domineering, and, in later years at any rate, was never quite sure of his support.

(3) Herbert Tracey, The Book of the Labour Party (1925)

It was inevitable that this great calamity (the First World War) should produce profound differences of opinion within the Labour Movement. These differences came to a head within the Parliamentary Labour Party at the very beginning of hostilities. It lies chiefly to the credit of two men, Mr. Henderson and Mr. MacDonald, that the issue which divided the Movement did not at the same time tears it asunder and wreck the political organisation which had been built up: their patience, common sense, and far-sightedness served to keep the party united, tolerant of the differences within its ranks, and resolute to prevent anything being said or done that would make it impossible for the leaders holding opposite opinions upon the War to be reconciled and to work together again for common causes when the delirium of war had passed.

(4) Bruce Glasier, diary entry (May, 1915)

This is the first instance of a member of the Labour Party joining the government. Henderson is a clever, adroit, rather limited-minded man - domineering and a bit quarrelsome - vain and ambitious. He will prove a fairly capable official front-bench man, but will hardly command the support of organised Labour.

(5) Herbert Tracey, The Book of the Labour Party (1925)

For many months before Mr. Henderson's visit to Russia the British Labour Movement had been taking a great deal of interest in democratic diplomacy. The Russian Revolution had quickened its instinct for a, democratic settlement of the War, and discussions were taking place upon the proposal to hold an inter-allied conference of the Labour and Socialist Parties with the ultimate aim of re-establishing the unity of the International which had been shattered when war broke out. Matters had reached the stage, early in 1917, at which it was decided to issue invitations for such a conference when the leaders of the Russian Revolution, not yet at the point of passing into its second or Communist phase, when Kerensky was superseded by Lenin, announced their intention of calling all the Labour and Socialist Parties into conference with the object of framing a general working-class peace policy. This was the beginning of the famous "Stockholm Conference" controversy which produced such remarkable results. Among the orthodox statesmen responsible for the conduct of the War there was great opposition to the project of calling this international Labour and Socialist Conference. They were beginning to fear the vigorous self-assertion of organised Labour in the field of international diplomacy and were apprehensive of the future course of the revolutionary movement in Russia. The War Cabinet had taken the step of sending Mr. Henderson on a Government mission to Russia, with instructions to investigate the situation and to remain there as Ambassador if he felt the state of affairs warranted his taking control. As one who was bent on the resolute prosecution of the War until German militarism had been decisively overthrown, Mr. Henderson went to Russia with an open mind about the proposal to hold an international Labour and Socialist Conference on the lines indicated by the Russian revolutionary leaders, which had taken the place of the more limited conference proposed by the Allied Socialists. He had not committed himself. Unlike the Prime Minister, Air. Lloyd George, he was not then satisfied that the proposed Conference would serve the purpose anticipated: but he went to Russia with the knowledge that Mr. Lloyd George believed at that time that if the Conference were held it would be dangerous to allow it to assemble without representatives of French Socialism and British Labour.

In Russia, after a close examination of the situation from both the political and the military point of view, Mr. Henderson formed definite conclusions which were communicated as a matter of course to the War Cabinet and also to the national executive of the Labour Party. One conclusion was that it was eminently desirable to hold the proposed conference for the purpose of consultation on the question of democratic war aims but without binding resolutions. He returned home at the same time as a deputation of four Russian revolutionary representatives arrived in this country; and in the ensuing discussions it became clear that the Russians wanted the Conference to take binding decisions, and meant to hold the conference, with or without the participation of the British working-class leaders. Mr. Henderson accompanied a deputation of the national executive of the Labour Party which went to Paris to discuss the Russian invitation with the leaders of French Socialism, and at that meeting arrangements were made for the calling of the Conference at Stockholm, in September of that year (1917). To give effect to the decision as far as British Labour was concerned it was decided by the national executive to summon a special party conference.

At this conference, held in London on 10th August, 1917, Mr. Henderson made a full statement of the conclusions he had reached and of the considerations that had influenced him in recommending that the Russian invitation should be accepted. He insisted that the conference was to be held purely for purposes of consultation and that no obligatory decisions were to be taken. It was well understood by this time that the Government was opposed to the holding of the Stockholm Conference. For reasons that are still obscure, Mr. Lloyd George had changed his mind-and apparently he expected that Mr. Henderson would change his, with equal facility. Among his colleagues in the Labour Party there was a group which also expected Mr. Henderson to change his mind. But once made up, Mr. Henderson's mind is not easily changed when an issue of principle is concerned, and he firmly adhered to the view he had taken, repeating at the special party conference the advice he had given to the national executive that British Labour should participate in the Stockholm Conference on the prescribed conditions. By the Government and the press it was apparently expected that the special party conference would reject Mr. Henderson's advice. A resolution was actually proposed at the conference to the effect that no case had been made out for the holding of the Stockholm Conference : this being put as an amendment to the executive resolution proposing that the Russian invitation should be accepted on condition that the Conference should be consultative and not mandatory. Until Mr. Henderson made his statement and expressed his view the issue was in doubt, but there was no room to doubt thereafter: by 1,651,000 votes to 301,000 the amendment was rejected and the executive resolution adopted as a substantive motion by the overwhelming vote of 1,846,000 to 550,000.

As a result of the attitude he had taken up on this question Mr. Henderson was bitterly attacked. He was charged with having misled the party conference by withholding from it information regarding the alleged change of view on the Stockholm proposal held by the Russian revolutionary Government. This charge will not bear a moment's examination. He told the delegates at the special party conference that since his return from Russia there had been a change in the situation there, for the first Provisional Government had been replaced by the Administration formed by Kerensky. He also stated that the Belgian Socialists and American Labour had decided not to participate in the Stockholm Conference; that an influential group of French Parliamentary Socialists were opposed to the project; and that the Russian Socialists demanded a binding conference and not merely a consultation. But he nevertheless made it plain that he considered the Stockholm Conference would serve a useful purpose in showing clearly to the world - and to the German people in particular-what the Allied democracies conceived themselves to be fighting for. The divergence of policy between him and the War Cabinet thus became clear, and he resigned from the Government.

(6) Ramsay MacDonald appointed Clement Attlee as Postmaster General in 1929. He wrote about MacDonald's government in his autobiography, As It Happened (1954)

Many members of the Government, of whom I was one, were seriously disturbed at the lack of constructive policy displayed by the leaders of the Government. We were also conscious of a growing estrangement between MacDonald and the rest of the Party. He was increasingly mixing only with people who did not share the Labour outlook. This opposition, however, did not crystallise, because the one man who could have taken MacDonald's place, Arthur Henderson, was too loyal to lend himself to any action against his leader.

Instead of deciding on a policy and standing or falling by it, MacDonald and Snowden persuaded the Cabinet to agree to the appointment of an Economy Committee, under the chairmanship of Sir George May of the Prudential Insurance Company, with a majority of opponents of Labour on it. The result might have been anticipated. The proposals were directed to cutting the social services and particularly unemployment benefit. Their remedy for an economic crisis, one of the chief features of which was excess of commodities over effective demand, was to cut down the purchasing power of the masses. The majority of the Government refused to accept the cuts and it was on this issue that the Government broke up. Instead of resigning, MacDonald accepted a commission from the King to form a so-called 'National' Government.

(7) C. P. Duff, Ramsay MacDonald's private secretary, memo (25th August, 1931)

On the Prime Minister's instructions I went to see Mr. Henderson at the Foreign Office this morning. I told him that the P.M was contemplating a Resignation Honours List; and would Mr. Henderson press him to give effect to the suggestions which had been made before, that Mr. Henderson should be given a Peerage? Mr Henderson said that the situation had now changed. A hard fight lay before the Labour Party, the more so as some of their erstwhile leaders had parted from them for the time being. He himself had served with the Party for over 40 years: for over 20 years he had been their Secretary: it was due to the Party that he occupied in public life the position which he did. At such a vital time in the fortunes of the Party it would need all the assistance it could get: responsible guidance within it would also be more needed than ever and his going to the House of Lords might impair the help & guidance which he could give them by remaining as he was. Also, Mrs. Henderson was away, and he would want to ask her: how soon did the P.M. want a reply? (I said tomorrow would do.) ... In a general conversation in which I said that we stood at the parting of the ways, Mr Henderson said that we must not take this too seriously. At the time of the war when Mr MacDonald left the Party he (Henderson) had kept it together and it was ready to receive Mr MacDonald back again. He was parting with the P.M. now in no spirit of anger or resentment; and as regards myself as I said goodbye, he observed "I could never quarrel with anyone whose wife came from Newcastle".