1922 General Election

Alan Percy, 8th Duke of Northumberland, had been an opponent of David Lloyd George since he had attacked his father, Henry Percy, 7th Duke of Northumberland, for exploiting land values. Northumberland held extreme right-wing views who financed and directed The Patriot, a weekly newspaper which published Nesta Webster and promoted a mix of anti-communism and anti-semitism. Webster argued that communism was a Jewish conspiracy. (1)

On 17th July, 1922, Northumberland made a speech attacking the way Lloyd George had been selling honours: "The Prime Minister's party, insignificant in numbers and absolutely penniless four years ago, has, in the course of those four years, amassed an enormous party chest, variously estimated at anything from one to two million pounds. The strange thing about it is that this money has been acquired during a period when there has been a more wholesale distribution of honours than ever before, when less care has been taken with regard to the service of the recipients than ever before and when whole groups of newspapers have been deprived of real independence by the sale of honours and constitute a mere echo of Downing Street from where they are controlled."

Northumberland read out from a letter that suggested that you could obtain a knighthood for £12,000 and a baronetcy for £35,000. "There are only five knighthoods left for the June list. If you decide on a baronetcy, you may have to wait for the Retiring List ... It is not likely that the next government will give so many honours and this is an exceptional opportunity." The letter ended with the comment: "It is unfortunate that Governments must have money, but the party now in power will have to fight Labour and Socialism, which will be an expensive matter." (2)

Northumberland argued that Lloyd George had used the honours system to encourage the newspapers not to criticise him. Lloyd George had in fact ennobled six proprietors during the last few years. Over a period of time the Conservative Party had given honours to all the important press lords. This included Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (The Daily Mail and The Times), Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere (The Daily Mirror), Harry Levy-Lawson, Lord Burnham (The Daily Telegraph) and William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (The Daily Express). As a result, their newspapers continued to criticise Lloyd George. (3)

David Lloyd George responded to the charges made by the Duke of Northumberland by admitting that: "As to the question of bargain and sale, I agree with everything that has been said about that. If it ever existed, it was a discreditable system. It ought never to have existed. If it does exist, it ought to be terminated, and if there were any doubt on that point, every step should be taken to deal with it." But he insisted that making donations to a political party should not exclude the receipt of an honour which was justified if they had been involved in "good works". He announced the setting up of a Royal Commission with a remit to recommend how the honours system could be "insulated from even the suggestion of corruption". (4)

The following month Lloyd George had to defend himself from the charge of profiteering from the First World War when The Evening Standard revealed that a United States publisher had offered £90,000 for the American rights to his memoirs. (5) It was claimed that he was going to make a fortune out of a conflict in which so many men had died. The public outcry far exceeded the expressions of distaste which were provoked by the honours scandal. After two weeks of hostile newspaper articles, Lloyd George made a statement that the money would be "devoted to charities connected with the relief of suffering caused by the war." (6)

At a meeting on 14th October, 1922, two younger members of the government, Stanley Baldwin and Leo Amery, urged the Conservative Party to remove Lloyd George from power. Andrew Bonar Law disagreed as he believed that he should remain loyal to the Prime Minister. In the next few days Bonar Law was visited by a series of influential Tories - all of whom pleaded with him to break with Lloyd George. This message was reinforced by the result of the Newport by-election where the independent Conservative won with a majority of 2,000, the coalition Conservative came in a bad third.

Another meeting took place on 18th October. Austen Chamberlain and Arthur Balfour both defended the coalition. However, it was a passionate speech by Baldwin: "The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right." The motion to withdraw from the coalition was carried by 187 votes to 87. (7)

David Lloyd George was forced to resign and his party only won 127 seats in the 1922 General Election. The Conservative Party won 344 seats and formed the next government. The Labour Party promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats, whereas the Liberal Party increased their vote and went from 36 to 62 seats. (8)

Lloyd George was never to hold office again. A. J. P. Taylor wrote: "He (David Lloyd George was the most inspired and creative British statesman of the twentieth century. But he had fatal flaws. He was devious and unscrupulous in his methods. He aroused every feeling except trust. In all his greatest acts, there was an element of self-seeking. Above all, he lacked stability. He tied himself to no man, to no party, to no single cause. Baldwin was right to fear that Lloyd George would destroy the Conservative Party, as he had destroyed the Liberal Party." (9)

| Political Parties | Total Votes | % | MPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Party | 5,502,298 | 38.5 | 344 |

| Liberal Party | 2,668,143 | 18.9 | 62 |

| National Liberals | 1,471,317 | 9.9 | 53 |

| Labour Party | 4,237,349 | 29.7 | 142 |

| Communist Party | 33,637 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Irish Nationalists | 102,667 | 2.4 | 10 |

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Cole, Growing Up Into Revolution (1949)

Lloyd George came into public life as a great Radical and who, as his later history showed, retained so much of real radicalism in his heart, should at that moment, of all moments, have chosen to hang on to personal power at the price of giving way to the worst elements in the community - only to be cast out by the Tories like an old shoe, when he had served his purpose, killed the Liberal Party, and deceived the working class so thoroughly that they would never trust him again.

(2) Alan Percy, 8th Duke of Northumberland, speech in the House of Lords (17th July, 1922)

The Prime Minister's party, insignificant in numbers and absolutely penniless four years ago, has, in the course of those four years, amassed an enormous party chest, variously estimated at anything from one to two million pounds. The strange thing about it is that this money has been acquired during a period when there has been a more wholesale distribution of honours than ever before, when less care has been taken with regard to the service of the recipients than ever before and when whole groups of newspapers have been deprived of real independence by the sale of honours and constitute a mere echo of Downing Street from where they are controlled.

(3) David Lloyd George, speech in the House of Commons (17th July, 1922)

The question is, Are men to be ruled out because of such contributions? If you do not rule men out because they have contributed, you will always be liable to the retort that that has influenced you. My hon. Friends do not suggest that, and no one suggests it. If the system of party political honours is to be terminated, let the House deliberately make up its mind on that subject. But before they do so, I ask them gravely to reflect on what will happen. There will be a gap to be filled up, and we have to consider what will be the effect. As to the question of bargain and sale, I agree with everything that has been said about that. If it ever existed, it was a discreditable system. It ought never to have existed. If it does exist, it ought to be terminated, and if there were any doubt on that point, every step should be taken to deal with it.... But, seeing that this system - the system of reward for political services - is one which has obtained, not merely in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but in the nineteenth century, under the most distinguished leadership the country has over seen, the country ought to consider very seriously before it brings it to an end.

The point is, does Parliament really wish to terminate the system by which service to party is rewarded in this country? If so, I should like them to remember that it is a system which has been evolved by the sagacity and by the experience of the people who have the longest experience and made the greatest success of representative institutions. It has the sanction of the noblest and purest names in British history. It may be illogical, like most of our institutions. I do not say that, because great men of the past have either founded or sanctioned institutions as suitable to their time, these institutions ought to be continued when times have changed. But, at any rate, the fact that they were so sanctioned is prima facie evidence that they ought to be continued until an overwhelming case is made out against them.

If that system be abolished, what will be the substitute? The Labour party, naturally, do not feel the same difficulty. They have other means of dealing with the situation. They have their own organisations in the country. But I would only utter one word of warning to them. When the time comes, when they have responsibility for the Government of this country, they will find the system, which may be helpful to them now, entangling their steps and destroying their independence. They will find themselves committed to positions from which it will be very difficult for them to extricate themselves. I do not say another word on that subject. I am only putting forward a consideration which must be in the minds of the most thoughful of them.

Turn to the countries which have not adopted our method of encouraging party service - if you like, of rewarding party service. There is nothing dishonourable in rewarding an honourable act of service, but human nature is very mixed in its motives. Some of the worst natures very often surprise you by revealing veins of golden goodness that you would never suspect, and if you strike with a pickaxe into some of the best, they reveal streaks of rather poor metal. Bui whether a man be of the best or of the worst, an encouragement, a stimulus, a reward for him to do his duty always helps him along. If you abolish this system, there are two alternatives, and I want the House solemnly to consider them. I speak now as a fairly old politician, who has been a Member of this House for over thirty-two years, who believes in representative institutions, believes in the House of Commons, believes it is the finest Assembly of its kind in the whole world, and I want the House carefully to consider, before it puts an end to the system, either by deliberate Resolution, or by making it impossible to carry on, what is the alternative to the system. Hon. Members opposite for some time, until they accept greater responsibilities, will be able to manage. The danger is that political organisation will collapse, and the alternative to political organisation is political chaos.

I know it is rather a cant in certain circles to gibe at politicians. Anybody who is afflicted with that disease should read what the great men of Germany have said as to the failure of their country. There is not one of them - admirals, generals, princes - who does not attribute it entirely to the fact that Germany had no politicians. Some of the worst blunders that have ever been committed could have been avoided had they had the trained political machine. Her organisation of resources behind the lines would have been better done and better distributed if Germany had had better politicians, as we had on our side. There is one most remarkable, and I always think most inexplicable, fact in the history of the War: That is the sudden collapse of Germany in 1918. Look at the reasons which are assigned for it. It would never have happened had Germany had political organisation, skilled and trained and organised for the purpose of appealing to the national sentiment, and arousing the national spirit. Whether in peace or in war, the nation that is politically organised is twice as safe as the nation which is not.

Another alternative is one which anyone can see for himself if he only look at what is happening in other great democratic countries just as free as ourselves, just as proud as ourselves, just as resentful of corruption as ourselves. Let anyone who cares to look into the matter read some of the authorities, classical authorities accepted for their impartiality even by those countries themselves. These are alternatives which I ask the House to consider very carefully before they make up their minds that they are going to strike out the whole of the honours recommendations made as rewards for political services.

Well, then, if that be a question of purchase and sale in honours, of traffic in honours, there is no disagreement in any part of the House, and I can assure the House of Commons I am not standing up on behalf of the Government to defend any system of that kind. I am here to say that neither by this Government, nor, I am perfectly certain, by any of its predecessors, has any system of that kind ever been sanctioned in this country. If the House - as I agree it is entitled, having regard to the discussions from time to time - if the House of Commons wants a reassurance, and the public wants a reassurance, then the Government are all for a re-examination of the methods of submitting the names.

The responsibilities of the chief Minister must, in our judgment, remain. You cannot transfer that responsibility to anyone else. He is the man who is responsible to the Sovereign, he is the man who is responsible to public opinion, and he is the man who must be responsible to the House of Commons. He is the man who can be arraigned, and who should be arraigned. Therefore no Committee which you set up can relieve the Chief Minister of the Crown of the main, and as far as the House of Commons is concerned, the sole responsibility for the advice given to the Sovereign. The whole question is whether there is any method by which you can strengthen his hands, and help him to discharge a difficult, delicate and individious task. Ministers for some years in the past have been—and Ministers for some years in the future, especially leading Ministers - are 1769 going to be so charged with burdens of all kinds in reference to the complications of public affairs, that any assistance that can be given them in the discharge of duties of this kind will be welcomed by them, and will be helpful to them. My hon. Friend (Mr. Locker-Lampson), in the beginning of his speech, made three or four suggestions that in his mind would perhaps meet the case. But I do not agree. They were all suggestions for taking the duty and the responsibility off the shoulders of the Chief Minister of the Crown, and if they were adopted, his responsibility would disappear. But I am not going to discuss the various suggestions which he made. That is obviously a question that ought to be considered calmly - not in the atmosphere of a Debate, where you have charges and counter-charges, but quietly, by men who are quite independent.

As it would deal with the prerogative of the Crown, it must be a Royal Commission, and the Government is prepared to assent to the appointment of a Royal Commission, to consider and advise on the procedure to be adopted in future to assist the Prime Minister in making recommendations to His Majesty of the names of persons deserving of special honour. I agree with my hon. Friend that the men who constitute that Commission must be men whose authority would be accepted by the whole of Parliament and the whole of the public. That is vital. They must be men whose independence, whose integrity, and whose experience, are above reproach.

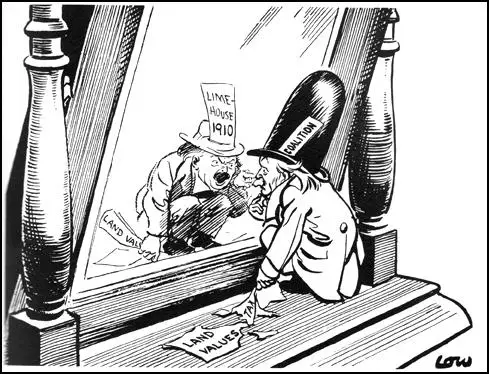

(4) David Low, Autobiography (1956)

David Lloyd George was the best-hated statesman of his time, as well as the best loved. The former I have good reason to know; every time I made a pointed cartoon against him, it brought batches of approving letters from all the haters. Looking at Lloyd George's pink and hilarious, head thrown back, generous mouth open to its fullest extent, shouting with laughter at one of his own jokes, I thought I could see how it was that his haters hated him. He must have been poison to the old school tie brigade, coming to the House an outsider, bright, energetic, irrepressible, ruthless, mastering with ease the House of Commons procedure, applying all the Celtic tricks in the bag, with a talent for intrigue that only occasionally got away from him.

I always had the greatest difficulty in making Lloyd George sinister in a cartoon. Every time I drew him, however critical the comment, I had to be careful or he would spring off the drawing-board a lovable cherubic little chap. I found the only effective way of putting him definitely in the wrong in a cartoon was by misplacing this quality in sardonic incongruity - by surrounding the comedian with tragedy.

(5) Stanley Baldwin, speech at a meeting of Conservative Party members of Parliament (19th October, 1922)

The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right.

(6) After the 1922 General Election, Margot Asquith, the wife of Herbert Asquith , wrote to C. P. Scott criticizing his decision to support David Lloyd George in his campaign to be re-elected (21st November, 1922)

I feel very bitter about Lloyd George; his is the kind of character I mind most, because I feel his charm and recognize his genius; but he is full of emotion without heart, brilliant with intellect, and a gambler without foresight. He has reduced our prestige and stirred up resentment by his folly - in India, Egypt, Ireland, Poland, Russia, America, and France.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject