Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, the only child of the industrialist, Alfred Baldwin and Louisa MacDonald Baldwin, was born in Bewdley on 3rd August 1867. His father was a prosperous ironmaster and the sole proprietor of the sheet-metal firm of E.P. & W. Baldwin. He was also chairman of the Great Western Railway. (1)

Baldwin's mother came from an artistic background. Her sister, Agnes MacDonald, married the painter Sir Edward John Poynter. Another sister, Georgiana MacDonald, married the painter Edward Coley Burne-Jones. A third sister, Alice MacDonald married the art teacher, John Lockwood Kipling and were the parents of the writer Rudyard Kipling. (2)

Baldwin was proud of his Quaker background: "I owe my Quaker strain to the earliest days of the Quakers. One of my ancestors went out in the reign of William III as a missionary to the American colonies. He devoted half a century to missionary life there and in the West Indies, where ultimately he died, leaving a name that was perhaps the most prominent and best known of the Quaker missionaries in those colonies. Now, that Quaker blood is peculiarly persistent, and I attribute to that a certain obstinacy I find existing in otherwise one of the most placable dispositions of any man I ever met. I find sometimes that when I conceive a matter to be a matter of principle I would rather go to the stake than give way." (3)

In May 1878 Baldwin went to Hawtrey's Preparatory School at Slough, where he was active in sports and won eighteen prizes, coming top of the school. In 1881 he became a pupil of Harrow School. During his first four years won form prizes for history and mathematics, and competed in football, cricket, and squash. In June 1883 his father was summoned by a telegram from the headmaster, Dr Montagu Butler, owing to an item of juvenile pornography which Stanley had written and sent to his cousin Ambrose Poynter at Eton. Alfred Baldwin told his wife that the affair was "much exaggerated and far more folly than anything else" but the incident had a long-term impact on his studies and in the sixth form his work deteriorated as he assumed an attitude of detachment and laziness. (4)

In the autumn of 1885 he went up to Trinity College where he read for the historical tripos. It was claimed that at university he was "shy, diffident, and bad at coping with emergencies". Baldwin's son and biographer, Arthur Windham Baldwin, the author of My Father: The True Story (1955) believes that it was his time at university "which produced the curious nervous symptoms, twitching of the face and snapping of the fingers, that became such noticeable features of his father behaviour in later life." (5)

Baldwin came under the influence of William Cunningham, the chaplain of his college and a lecturer in economics. He provided theoretical support for the conviction that the interests of workers and employers were, over time, identical. Philip Williamson, the author of Stanley Baldwin (1999) has argued that Cunningham taught him that "an economic, moral and Christian Conservatism as the positive and truly national alternative to both Liberalism and socialism." (6) Cunningham also introduced Baldwin to the ideas of Arnold Toynbee, the founder of the settlement Toynbee Hall, where he worked during his vacations. (7)

According to Roy Jenkins: "Baldwin read history and achieved a steady deterioration in each year's performance. He got a First at the end of his first year, a Second at the end of his second, and a Third at the end of his third. But more surprising than his lack of academic prowess was his failure to make any sort of impact. He made few friends; he joined few clubs or societies, and after being elected to the college debating society was asked to resign because he never spoke." (8) When he graduated from Cambridge University with a third class degree his father said: "I hope you won't have a Third in life." (9)

Alfred Baldwin was a member of the Conservative Party and in 1892 was elected as member of parliament for the local constituency of Bewdley. That year Baldwin married Lucy Ridsdale. Over the next few years she gave birth to two sons and four daughters. Baldwin worked for his father's business and in 1898 he oversaw the company's flotation on the Stock Market, and in 1902 the rationalisation of its various parts were amalgamated into Baldwins Ltd together with other steelworks and collieries in south Wales. A series of horizontal and vertical mergers brought the whole iron-working process, from commodity extraction to finishing, under one umbrella. It had a publicly-quoted value of £1 million (about £62 million at today's prices) and employed about 4,000 workers, which put it among the hundred largest companies in Britain. (10)

Stanley Baldwin: Member of Parliament

In 1904 Stanley Baldwin was selected for the Conservative safe seat of Kidderminster. However, in the 1906 General Election, the Liberal Party achieved a landslide victory and lost the seat to Edmund Broughton Barnard. In 1908 his father died and he inherited nearly £200,000 (£15 million in today's money) and was offered his parliamentary seat of Bewdley. After an unopposed return was introduced into the House of Commons on 3rd March 1908. (11)

In his maiden speech he used his own business experience to explain his views on trade unions: "I might mention, not as of any interest to the House, but merely as showing what the House might expect of me in the way of fair debate, that although my family had been engaged for 130 years in trade, the disputes they had had with their men could be numbered on the fingers of one hand. I myself have been in active business for twenty years, and have never had the shadow of a dispute with any of my own men, and I gave my men in the sheet-rolling trade an eight-hour day long before the question excited any interest in the House or the country. (12)

Baldwin's first biographer, Adam Gowans Whyte, attempted to explain why he entered politics so late in life: "Experience in manufacturing and in trade is a valuable asset to a politician, but distinguished success in these spheres leaves a man little enough time for the duties of an ordinary member of the House of Commons. Moreover, the qualities which make for high achievement in the factory or counting-house are not identical with those which must be cultivated by the leader of a party or a popular statesman... In the case of Mr. Baldwin, there was also a transition from business to politics, but it was of a less deliberate and drastic character. He may be said to have inherited the double strain of industry and public service, since he succeeded both to his father's business and to his father's seat in the House of Commons." (13)

Baldwin held progressive political ideas and was one of twelve Conservative MPs who voted for the second reading of the Old Age Pensions Act in 1908, and he approved the principle of the National Insurance Act. However, he only made only five speeches in his first six years. One of these was over the issue of "unfair competition of foreign producers in British markets, and in the high tariffs of foreign countries, has caused capital to be employed abroad which might have been used at home to the great advantage of the wage-earning population of the country." (14)

On the outbreak of the First World War he was forty-seven, and too old for military service. He encouraged his own workers to join the armed forces by paying out of his own pocket, the Friendly Society subscriptions. Arthur Bonar Law, appointed Baldwin as his parliamentary private secretary, and by late 1916 he gave his support to David Lloyd George in his plot to overthrow H. H. Asquith, the prime minister. (15)

Lloyd George brought Baldwin into his government as Financial Secretary to the Treasury and President of the Board of Trade. He was a few weeks short of his fiftieth birthday, a somewhat elderly junior minister. He held the post for the next four years. He served under two Chancellors, Bonar Law and Austen Chamberlain. He admired rather than liked Lloyd George. He would often have breakfast with the prime minister and wrote: "The breakfasts give me a good opportunity of studying that strange little genius who presides over us. He is an extraordinary compound." (16)

Baldwin became very attached to Joan (Mimi) Dickinson, the 18-year-old friend of one of his daughters. In April 1918 he introduced her to John C. Davidson, one of junior aides. Davidson later recalled: "I was very shy and reluctant to take part in it at all and I thought it was terrible to be wasting time. When I reached the drawing room, I looked around and saw standing on the stairs a girl talking to SB (Stanley Baldwin). I went up to them and he introduced me. And I said to myself then and there, this is the girl I am going to marry. I asked her for a dance and she accepted.... I was invited to stay at Astley with the Baldwins and Mimi was there. I proposed to her and she turned me down. In fact, she turned me down pretty regularly until at long last, on New Year's Eve, 1918... We went back to Portland Place where my parents lived and then to Egerton Gardens where her parents were living and announced our engagement." (16a)

Her mother had doubts about Mimi's choice of a husband. Baldwin decided to write her a letter: "Mimi has chosen a partner of the right age. She might have married a man of fifty or a boy of twenty. You are spared that. They start equal: with the outlook of the same generation, with the prospect of passing their youth together, of entering middle life and old age together. Then - and for this a father and mother should thank God daily - you are giving your child to a man with a mind as clean as the north wind, whose whole life's attitude towards women makes him worthy of the trust you are placing in him... There is no need of anxiety, believe me. I know them both and love them both, and I believe that in a few years you will look back and bless this day, and, who knows, you may even have a kind word for the man who first brought them together!" (16b)

The couple married on 9th April 1919. Joan was the younger daughter and second of three children of Willoughby Hyett Dickinson, barrister and Liberal MP, and his wife, Minnie Elizabeth Gordon Cumming, daughter of General Richard John Meade. It was a close and happy marriage and resulted in two sons and two daughters (Margaret, Jean, Andrew and Malcolm). Baldwin remained a close friend of Mimi's and he wrote on average three times a week for twenty-five years to her. (16c)

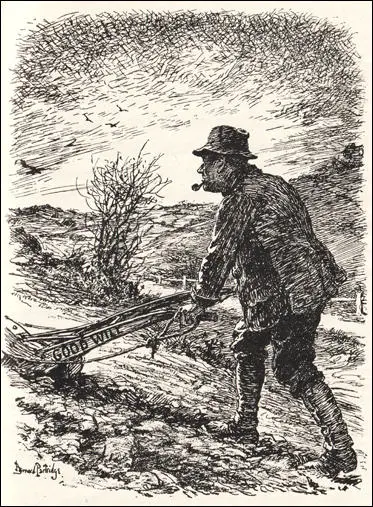

Baldwin's company continued to grow and it is estimated that his fortune had reached £600,000 ((£45 million in today's money). "He enjoyed cricket in the summer and mixed hockey matches in the winter. He was a great walker... The Baldwins lived modestly... He disliked ostentation and high living. It was perhaps part of the puritan inheritance from his ancestors that he preferred to spend his money on charity rather than on the adornment of his house or the provisioning of his table." (17) As one of his biographers pointed out, he had discovered that "goodwill was no alternative to taxation". (18)

Baldwin was embarrassed by the huge profits made by his company during the First World War and in June, 1919, Baldwin had an anonymous letter to The Times where he appealed to the "wealthy classes" to help deal with the national debt. "I have made as accurate an estimate as I am able of the value of my own estate, and have arrived at a total of about £580,000. I have decided to realise 20% of that amount or say £120,000 which will purchase £150,000 of the War Loan, and present it to the Government for cancellation. I give this portion of my estate as a thank-offering in the firm conviction that never again shall we have such a chance of giving our country that form of help which is so vital at the present time." (19)

As one biographer pointed out: "The gesture was generous and public spirited, with an element of naïveté about it. The anonymity (not perhaps best protected by the choice of pseudonym) held just long enough for Baldwin to be alone in the secret amongst those present when he performed his statutory Financial Secretary's duty of witnessing the burning of the cancelled bonds, but not for much longer. And the attempt to start an avalanche of donations was a complete failure. Baldwin had aimed by his example at a debt reduction of £1,000 million. In the result only about £1½ million, including his own gift, was received." (20)

Baldwin found politics very frustrating and in 1921 stated that "many times in the life of anyone who is working in Parliament and in the Government, and in times like these, one feels that one would like to throw the whole thing up, get out of the country, and never come back again." In another speech he said that he was looking forward to retirement so he could devote himself to the things he enjoyed: "I look forward to the time when I can pick up the books in my library that are now covered with dust, which I never have time to look at, when I can devote myself to studies and to delights of that kind from which I have been too long alienated." (21)

In March 1921 Baldwin was promoted to be President of the Board of Trade and joined the Lloyd George Coalition Cabinet. The prime minister gradually lost the support of his Cabinet colleagues. After Edwin Montagu resigned in March 1922, he criticised the style of Lloyd George's leadership: "We have been governed by a great genius - a dictator who has called together from time to time conferences of Ministers, men who had access to him day and night, leaving all those who, like myself, found it impossible to get him for days together. He has come to epoch-making decisions, over and over again. It is notorious that members of the Cabinet had no knowledge of those decisions." (22)

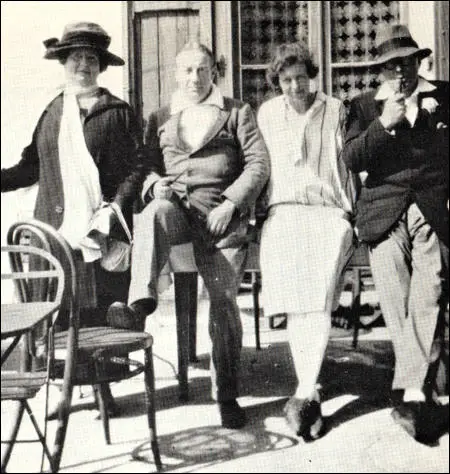

Stanley and Lucy Baldwin often went on holiday to Aix-les-Bains with the much younger, John C. Davidson and Joan Davidson. Lucy Baldwin, did not share her husband's "intellectual or aesthetic tastes, and did not accompany him on the long walks which were a staple part of his recreation in Worcestershire or at Aix... and she allowed others, notably Mrs Davidson to take the walks." (22a)

John Davidson later wrote: "The Baldwins were regular visitors to Aix-les-Bains, and Mimi and I often joined them there. We used to walk with him while Mrs Baldwin took the baths... It is not easy to describe adequately the splendor of the scenery of Aix-les-Bains. The outline in the morning or the evening of Le Col du Chat and the stiff but marvellous walk along the escarpment are both never-to-be-forgotten memories... It gave such relaxation to SB (Baldwin), and constituted an essential contrast with the heat and burden of politics at home." (22b)

on holiday at Aix-les-Bains (August, 1923)

John C. Davidson entered the House of Commons as MP for Hemel Hempstead in November 1920. Davidson, who was a close friend of Andrew Bonar Law, became his parliamentary private secretary (PPS). When Law retired on health grounds in March 1921, Davidson became parliamentary private secretary to Stanley Baldwin. "Davidson shared with Baldwin and a range of junior ministers an increasingly negative view of the Lloyd George coalition. The revolt against this was a movement at many levels within the Conservative Party involving constituency pressure, back-bench MPs, junior ministers, and restive peers." (22c)

In August 1922 Lloyd George had to defend himself from the charge of profiteering from the First World War when The Evening Standard revealed that a United States publisher had offered £90,000 for the American rights to his memoirs. (23) It was claimed that he was going to make a fortune out of a conflict in which so many men had died. The public outcry far exceeded the expressions of distaste which were provoked by the honours scandal. After two weeks of hostile newspaper articles, Lloyd George made a statement that the money would be "devoted to charities connected with the relief of suffering caused by the war." (24)

Baldwin became convinced that Lloyd George was a corrupt politician who had sold appointments. He was also concerned that he was "casually destroying working class confidence in government by abandoning social reform, fudging the question of nationalising the coal mines and bodging compromises to end industrial disputes, all decisions that could only strengthen Labour's appeal." (25)

At a meeting on 14th October, 1922, Stanley Baldwin and Leo Amery, urged the Conservative Party to remove Lloyd George from power. Andrew Bonar Law disagreed as he believed that he should remain loyal to the Prime Minister. In the next few days Bonar Law was visited by a series of influential Tories - all of whom pleaded with him to break with Lloyd George. This message was reinforced by the result of the Newport by-election where the independent Conservative won with a majority of 2,000, the coalition Conservative came in a bad third. (26)

Another meeting took place on 18th October. Austen Chamberlain and Arthur Balfour both defended the coalition. However, it was a passionate speech by Baldwin: "The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right." (27)

J. C. C. Davidson commented: "The speeches which I remember best were of course Baldwin's and Bonar's. Balfour's was most inappropriate to the feeling at the meeting and Austen Chamberlain's was a lecture. Austen made quite a good speech from his point of view, but it was really idolatry, because it was a speech indicating that the only man who could really lead the country was the man who practically the whole of our party, especially the rebelling element in it, regarded as the most evil genius in the country, and who Baldwin subsequently described brilliantly as a dynamic force." As a result of the debate the motion to withdraw from the coalition was carried by 185 votes to 88. (27a)

David Lloyd George was forced to resign and his party only won 127 seats in the 1922 General Election. The Conservative Party won 344 seats and formed the next government under Andrew Bonar Law. The Labour Party promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats, whereas the Liberal Party increased their vote and went from 36 to 62 seats. (28)

Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, replaced David Lloyd George as prime minister. Baldwin was rewarded for his role in bringing down Lloyd George by becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer. Bonar Law's first task was to persuade the French government to be more understanding of Germany's ability to pay war reparations. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), agreed to 226 billion gold marks. In 1921, the amount was reduced to 132 billion. However, they were still unable to pay the full amount and by the end of 1922, Germany was deeply in debt. Bonar Law suggested lowering the payments but the French refused and on 11th January, 1923, the French Army occupied the Ruhr. (29)

Bonar Law also had the problem of Britain's war debt to the United States. In January 1923, Baldwin, sailed to America to discuss a settlement. Initially the loans to Britain had been made at an interest rate of 5 per cent. Bonar Law urged Baldwin to get it reduced to 2.5 per cent, but the best American offer was for 3 per cent, rising to 3.5 per cent after ten years. This amounted to annual repayments of £25 million and £36 million, rising to £40 million. Baldwin, acting on his own initiative, accepted the American offer and announced to the British press that they were the best terms available. Bonar Law was furious and on 30th January announced at cabinet that he would resign rather than accept the settlement. However, the rest of the cabinet thought it was a good deal and he was forced to withdraw his threat. (30)

The American settlement meant a 4 per cent increase in public expenditure at a time when Bonar Law was committed to a policy of reducing taxes and public expenditure. This brought him into conflict with the trade union movement that was deeply concerned by growing unemployment. Robert Blake, the author of The Conservative Party from Peel to Churchill (1970) argued that Bonar Law was not sure how the working class would react to this situation. Could they gain their support "by making moderate concessions" or to make "a direct appeal to the working-class over the heads of the bourgeoisie, a new form of Tory radicalism?" (31)

In the House of Commons he argued the case for the Conservative Party to move to the left. "I am myself of that somewhat flabby nature that always prefers agreement to disagreement...When the Labour Party sit on these benches, we shall all wish them well in their effort to govern the country. But I am quite certain that whether they succeed or fail there will never in this country be a Communist Government, and for this reason, that no gospel founded on hate will ever seize the hearts of our people - the people of Great Britain... No Government in this country today, which has not faith in the people, hope in the future, love for his fellow-men, and which will not work and work and work, will ever bring this country through into better days and better times, or will ever bring Europe through or the world through." (32)

In April 1923, Bonar Law began to have problems talking. On the advice of his doctor, Sir Thomas Horder, he took a month's break from work, leaving Lord George Curzon to preside over the cabinet and Stanley Baldwin to lead in the House of Commons. Horder examined Bonar Law in Paris on 17th May, and diagnosed him to be suffering from cancer of the throat, and gave him six months to live. Five days later Bonar Law resigned but decided against nominating a successor. (33)

J. C. C. Davidson, the Conservative Party MP, sent a memorandum to King George V advising him on the appointment: "The resignation of the Prime Minister makes it necessary for the Crown to exercise its prerogative in the choice of Mr Bonar Law's successor. There appear to be only two possible alternatives. Mr Stanley Baldwin and Lord Curzon. The case for each is very strong. Lord Curzon has, during a long life, held high office almost continuously and is therefore possessed of wide experience of government. His industry and mental equipment are of the highest order. His grasp of the international situation is great."

Davidson pointed out that Baldwin also had certain advantages: "Stanley Baldwin has had a very rapid promotion and has by his gathering strength exceeded the expectations of his most fervent friends. He is much liked by all shades of political opinion in the House of Commons, and has the complete confidence of the City and the commercial world generally. He in fact typifies the spirit of the Government which the people of this country elected last autumn and also the same characteristics which won the people's confidence in Mr Bonar Law, i.e. honesty, simplicity and balance."

Given their relative merits, Davidson believed that the king should select Baldwin: "Lord Curzon temperamentally does not inspire complete confidence in his colleagues, either as to his judgement or as to his ultimate strength of purpose in a crisis. His methods too are inappropriate to harmony. The prospect of him receiving deputations as Prime Minister for the Miners' Federation or the Triple Alliance, for example, is capable of causing alarm for the future relations between the Government and labour, between moderate and less moderate opinion... The time, in the opinion of many members of the House of Commons, has passed when the direction of domestic policy can be placed outside the House of Commons, and it is admitted that although foreign and imperial affairs are of vital importance, stability at home must be the basic consideration. There is also the fact that Lord Curzon is regarded in the public eye as representing that section of privileged conservatism which has its value, but which in this democratic age cannot be too assiduously exploited." (34)

Arthur Balfour, the prime minister between July, 1902 and December, 1905, was also consulted and he suggested the king could chose Baldwin. (35) "Balfour... pointed out that a Cabinet already over-weighted with peers would be open to even greater criticism if one of them actually became Prime Minister; that, since the Parliament Act of 1911, the political centre of gravity had moved more definitely than ever to the Lower House; and finally that the official Opposition, the Labour party, was not represented at all in the House of Lords." (36)

Stanley Baldwin became prime minister on 22nd May, 1923. He told the House of Commons: "I never sought the office. I never planned out or schemed my life. I have but one idea, which was an idea that I inherited, and it was the idea of service - service to the people of this country. My father lived in the belief all his life… It is a tradition; it is in our bones; and we have to do it. That service seemed to lead one by way of business and the county council into Parliament, and it has led one through various strange paths to where one is; but the ideal remains the same, because all my life I believed from my heart the words of Browning, 'All service ranks the same with God'. It makes very little difference whether a man is driving a tramcar or sweeping streets or being Prime Minister, if he only brings to that service everything that is in him and performs it for the sake of mankind." (37)

Baldwin was faced with growing economic problems. This included a high-level of unemployment. Baldwin believed that protectionist tariffs would revive industry and employment. However, Bonar Law had pledged in 1922 that there would be no changes in tariffs in the present parliament. Baldwin came to the conclusion that he needed a General Election to unite his party behind this new policy. On 12th November, Baldwin asked the king to dissolve parliament. (38)

During the election campaign, Baldwin made it clear that he intended to impose tariffs on some imported goods: "What we propose to do for the assistance of employment in industry, if the nation approves, is to impose duties on imported manufactured goods, with the following objects: (i) to raise revenue by methods less unfair to our own home production which at present bears the whole burden of local and national taxation, including the cost of relieving unemployment; (ii) to give special assistance to industries which are suffering under unfair foreign competition; (iii) to utilise these duties in order to negotiate for a reduction of foreign tariffs in those directions which would most benefit our export trade; (iv) to give substantial preference to the Empire on the whole range of our duties with a view to promoting the continued extension of the principle of mutual preference which has already done so much for the expansion of our trade, and the development, in co-operation with the other Governments of the Empire, of the boundless resources of our common heritage." (39)

The Labour Party election manifesto completely rejected this argument: "The Labour Party challenges the Tariff policy and the whole conception of economic relations underlying it. Tariffs are not a remedy for Unemployment. They are an impediment to the free interchange of goods and services upon which civilised society rests. They foster a spirit of profiteering, materialism and selfishness, poison the life of nations, lead to corruption in politics, promote trusts and monopolies, and impoverish the people. They perpetuate inequalities in the distribution of the world's wealth won by the labour of hands and brain. These inequalities the Labour Party means to remove." (40)

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (41)

Stanley Baldwin remained close to John C. Davidson and Joan Davidson. He wrote in December, 1923: "This is a time for hanging out signals to our friends. How can I tell you what you have been to me for yet another year? Life has nothing more precious than your friendship and I bless you for it every day. You will never how you help me and what have I done that I should have that amazing friendship that you and David give me, I know not. But I am grateful for it. And this is true, that the love that binds us three together makes it easier to generate that wider love that alone makes it possible to carry on in public life." (41a)

Baldwin made a speech on 3rd May, 1924, where he commented on the changes that were taking place in politics: "The government had no mandate to govern, and its members won their seats as a Socialistic vote, but were not carving out a Socialist policy. This could be only temporary. If words meant anything the Labour Party was a Socialist Party, and if they went back on socialism they were little more than a left wing of the Conservative Party. Socialism had certain obvious advantages, possessing cut and dried remedies for every evil under the sun, but Conservatives have been in the fore-front of the battle to help the people more… If we are to live as a party we must live for the people in the widest sense… Every future Government must be Socialistic." (42)

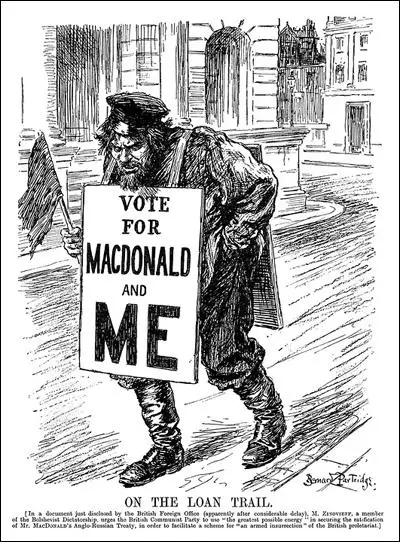

Zinoviev Letter

On 10th October 1924, MI5 received a copy of a letter, dated 15th September, sent by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, to Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were asked to take all possible action to ensure the ratification of the Anglo-Soviet Treaties. It then went on to advocate preparation for military insurrection in working-class areas of Britain and for subverting the allegiance in the army and navy. (43)

Hugh Sinclair, head of MI6, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect. (44) Vernon Kell, the head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson the head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the Zinoviev Letter was genuine. Desmond Morton, who worked for MI6, told Sir Eyre Crowe, at the Foreign Office, that an agent, Jim Finney, who worked for George Makgill, the head of the Industrial Intelligence Bureau (IIB), had penetrated Comintern and the Communist Party of Great Britain. Morton told Crowe that Finney "had reported that a recent meeting of the Party Central Committee had considered a letter from Moscow whose instructions corresponded to those in the Zinoviev letter". However, Christopher Andrew, who examined all the files concerning the matter, claims that Finney's report of the meeting does not include this information. (45)

Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret until it was discovered to be genuine. (46) Thomas Marlowe, who worked for the press baron, Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, had a good relationship with Reginald Hall, the Conservative Party MP, for Liverpool West Derby. During the First World War he was director of Naval Intelligence Division of the Royal Navy (NID) and he leaked the letter to Marlowe, in an effort to bring an end to the Labour government. (47)

The newspaper now contacted the Foreign Office and asked if it was a forgery. Without reference to MacDonald, a senior official told Marlowe it was genuine. The newspaper also received a copy of the letter of protest sent by the British government to the Russian ambassador, denouncing it as a "flagrant breach of undertakings given by the Soviet Government in the course of the negotiations for the Anglo-Soviet Treaties". It was decided not to use this information until closer to the election. (48)

David Lloyd George signed a trade agreement with Russia in 1921, but never recognised the Soviet government. On taking office the Labour government entered into talks with Russian officials and eventually recognised the Soviet Union as the de jure government of Russia, in return for the promise that Britain would get payment of money that Tsar Nicholas II had borrowed when he had been in power. (49)

A conference was held in London to discuss these matters. Most newspapers reacted with hostility to these negotiations and warned of the danger of dealing with what they considered to be an "evil regime". in August 1924 a wide-ranging series of treaties was agreed between Britain and Russia. "The most-favoured-nation status was given to the Soviet Union in exchange for concessions to British holders of Czarist bonds, and Britain agreed to recommend a loan to the Soviet government." (50)

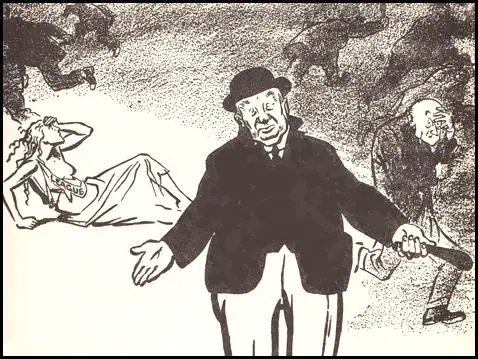

Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party, and H. H. Asquith, the leader of the Liberal Party, decided to being the Labour government down over the issue of its relationship with the Soviet Union. On 30th September, the Liberals condemned the recently agreed trade deal. They claimed, unjustly, that Britain had given the Russians what they wanted without resolving the claims of British bondholders who had suffered in the revolution. "MacDonald reacted peevishly to this, accusing them of being unscrupulous and dishonest." (51)

The following day, Conservatives put down a censure motion on the decision to drop the case against John Ross Campbell. The debate took place on 8th October. MacDonald lost the vote by 364 votes to 198. "Labour was brought down, on the Campbell case, by the combined ranks of Conservatives and Liberals... The Labour government had lasted 259 days. On six occasions the Conservatives had saved MacDonald from defeat in the 1923 parliament, but it was the Liberals who pulled the political rung from under him." (52)

1924 General Election

The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev Letter on 25th October 1924, just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind." (53)

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats. (54)

Stanley Baldwin, became prime minister again and set up a Cabinet committee to look into the Zinoviev Letter. On 19th November, 1924, the Foreign Secretary, Austin Chamberlain, reported that members of the committee were "unanimously of opinion that there was no doubt as to the authenticity of the Letter". This judgement was based on a report written by Desmond Morton. Morton came up with "five very good reasons" why he thought the letter was genuine. These were: its source, an agent in Moscow "of proved reliability"; "direct independent confirmation" from CPGB and ARCOS sources in London; "subsidiary confirmation" in the form of supposed "frantic activity" in Moscow; because the possibility of SIS being taken in by White Russians was "entirely excluded"; and because the subject matter of the Letter was "entirely consistent with all that the Communists have been enunciating and putting into effect". Gill Bennett, who has studied the subject in great depth claims: "All five of these reasons can be shown to be misleading, if not downright false." (55) Eight days later, Morton admitted in a letter to MI5 that "we are firmly convinced this actual thing (the Zinoviev letter) is a forgery." (56)

Baldwin wanted to appoint Neville Chamberlain as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Chamberlain, however, believed that whereas he might make a great Minister of Health he would only ever be a second-rate Chancellor and requested a move to the Department of Health. Baldwin accepted his arguments and appointed Winston Churchill as Chancellor. Chamberlain immediately embarked upon an ambitious programme of social reform in the areas of housing, health, local government, the extension of national insurance and widows' pensions. Over the next five years he proposed 25 pieces of progressive legislation, 21 of which became law. Graham Stewart argued that "under his guidance, the confused and complicated patchwork of local government was entirely rationalised by 1929 with a commanding sweep which - put to a different goal - would have been the envy of any totalitarian planner." (57)

Baldwin often came into conflict with Churchill over economic issues. Despite the problem of low Government revenues Churchill was determined not to increase personal taxes. In 1925 the majority of people did not pay income tax - only 2½ million people were liable and just 90,000 paid super-tax. The standard rate of income tax was reduced from four shillings and sixpence to four shillings in the pound. The super-tax was reduced by £10 million, which was substantial in relation to the total yield of the tax at £60 million: "This was of substantial benefit to the rich, not only as individual taxpayers but also in the capacity of many of them as shareholders, for income tax was then the principal form of company taxation." (58)

In a letter to James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury, the leader of the House of Lords, he argued that "the rich, whether idle or not, are already taxed in this country to the very highest point compatible with the accumulation of capital for further production." (59) In a second letter he stated that cutting taxes was a "class measure" that was designed "to help the comfortably off and the rich." (60)

Churchill's social conservatism was also apparent during discussions within the Government over changes to unemployment insurance. The scheme that the Liberal government had introduced in 1911 had collapsed after the war because of large-scale structural unemployment, particularly among trades that were not covered by the scheme. A benefit (the dole) was first introduced for unemployed ex-servicemen, later extended to others and then made subject to a means test in 1922. Churchill thought that far too many people were drawing the "dole". (61)

Winston Churchill spoke in the House of Commons of the "growing up of a habit of qualifying for unemployment relief" and the need for an enquiry. (62) Three weeks later he told Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary of the Cabinet, that "there should be an immediate stiffening of the administration, and the position should be made much more difficult for young unmarried men living with relatives, wives with husbands at work, aliens, etc." (63)

Churchill wrote to Arthur Steel-Maitland, the Minister of Labour, to explain his ideas. He suggested that when the legislation to pay for the dole expired in 1926, rather than reduce the benefit, as most of his colleagues wanted to do, they should abolish it altogether. Churchill said: "It is profoundly injurious to the state that this system should continue; it is demoralising to the whole working class population... it is charitable relief; and charitable relief should never be enjoyed as a right." Churchill told Steel-Maitland that the huge number of unemployed families would have to depend on private charity once their insurance benefits were exhausted. The Government might make some donations to charities but money would only be given to "deserving cases" and that "by proceeding on the present lines we are rotting the youth of the country and rupturing the mainsprings of its energies". (64)

Churchill attempted to get his ideas supported by Stanley Baldwin: "I am thinking less about saving the exchequer than about saving the moral fibre of our working classes." (65) Churchill did not get his way. The other members of the Government, including Neville Chamberlain, regardless of any possible moral consequences, could not face the political impact of ending the ‘dole' at a time when over a million people were out of work. (66)

In 1925 Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, urged the government to introduce legislation to reduce the powers of the trade union movement. It was a time of high employment and Churchill believed this was the time to hurt them when they were economically weak. As the government refused to act, a Conservative Party backbench MP, Frederick A. Macquisten, introduced a private members bill that would force trade union members to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party. Macquisten argued that "what I am proposing now is to relieve the working man of this liability to be taxed." (67)

Stanley Baldwin made a speech in the House of Commons on why he could not support this bill. "Those two forces with which we have to reckon are enormously strong, and they are the two forces in this country to which now, to a great extent, and it will be a greater extent in the future, we are committed. We have to see what wise statesmanship can do to steer the country through this time of evolution, until we can get to the next stage of our industrial civilisation. It is obvious from what I have said that the organisations of both masters and men - or, if you like the more modern phrase invented by economists, who always invent beastly words, employers and employees, these organisations throw an immense responsibility on the representatives themselves and on those who elect them... In this great problem which is facing the country in years to come, it may be from one side or the other that disaster may come, but surely it shows that the only progress that can be obtained in this country is by those two bodies of men - so similar in their strength and so similar in their weaknesses - learning to understand each other, and not to fight each other." (68)

The General Strike

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (69)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (70) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (71)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (72)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (73)

Red Friday was a great success for Herbert Smith and Arthur J. Cook. However, Margaret Morris has argued that they had a difficult relationship: "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics." (74)

The Royal Commission was established under the chairmanship of Sir Herbert Samuel, to look into the problems of the Mining Industry. The commissioners took evidence from nearly eighty witnesses from both sides of the industry. They also received a great mass of written evidence, and visited twenty-five mines in various parts of Great Britain. The Samuel Commission published its report on 10th March 1926. Interest in it was so great that it sold over 100,000 copies. (75)

The Samuel Report was critical of the mine owners: "We cannot agree with the view presented to us by the mine owners that little can be done to improve the organization of the industry, and that the only practical course is to lengthen hours and to lower wages. In our view huge changes are necessary in other directions, and the large progress is possible". The report recognised that the industry needed to be reorganised but rejected the suggestion of nationalization. However, the report also recommended that the Government subsidy should be withdrawn and the miners' wages should be reduced. (76)

Herbert Smith rejected the Samuel Report and told a meeting with representatives of the colliery owners: "We are willing to do all we can to help this industry, but it is with this proviso, that when we have worked and given our best, we are going to demand a respectable day's wage for a respectable day's work; and that is not your intention." He added: "Not a penny off the pay, not a second on the day." (77)

The National Union of Mineworkers was put in a difficult position when Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), welcomed the Samuel Report as a "wonderful document". A. J. Cook, at the MFGB conference advised delegates not to reject the report outright, so as not to jeopardise the support of the TUC. He was aware of the need to appear reasonable, but he also reaffirmed his opposition to wage reductions: "I am of the opinion we have got the biggest fight of our lives in front of us, but we cannot fight alone." (78)

Stanley Baldwin and his ministers had several meetings with both sides in order to avoid the strike. Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet, pointed out: "It is possible not to feel the contrast between the reception which Ministers give to a body of owners and a body of miners. Ministers are at ease at once with the former, they are friends jointly exploring a situation. There was hardly any indication of opposition or censure. It was rather a joint discussion of whether it was better to precipitate a strike or the unemployment which would result from continuing the present terms. The majority clearly wanted a strike." (79)

Considering themselves in a position of strength, the Mining Association now issued new terms of employment. These new procedures included an extension of the seven-hour working day, district wage-agreements, and a reduction in the wages of all miners. Depending on a variety of factors, the wages would be cut by between 10% and 25%. The mine-owners announced that if the miners did not accept their new terms of employment then from the first day of May they would be locked out of the pits. (80)

At the end of April 1926, the miners were locked out of the pits. A Conference of Trade Union Congress met on 1st May 1926, and afterwards announced that a General Strike "in defence of miners' wages and hours" was to begin two days later. The leaders of the Trade Union Council were unhappy about the proposed General Strike, and during the next two days frantic efforts were made to reach an agreement with the Conservative Government and the mine-owners. (81)

The Trade Union Congress called the General Strike on the understanding that they would then take over the negotiations from the Miners' Federation. The main figure involved in an attempt to get an agreement was Jimmy Thomas. Talks went on until late on Sunday night, and according to Thomas, they were close to a successful deal when Stanley Baldwin broke off negotiations as a result of a dispute at the Daily Mail. (82)

What had happened was that Thomas Marlowe, the editor the newspaper, had produced a provocative leading article, headed "For King and Country", which denounced the trade union movement as disloyal and unpatriotic.The workers in the machine room, had asked for the article to be changed, when he refused they stopped working. Although, George Isaacs, the union shop steward, tried to persuade the men to return to work, Marlowe took the opportunity to phone Baldwin about the situation. (83)

The strike was unofficial and the TUC negotiators apologized for the printers' behaviour, but Baldwin refused to continue with the talks. "It is a direct challenge, and we cannot go on. I am grateful to you for all you have done, but these negotiations cannot continue. This is the end... The hotheads had succeeded in making it impossible for the more moderate people to proceed to try to reach an agreement." A letter was handed to the TUC negotiators that stated that the "gross interference with the freedom of the press" involved a "challenge to the constitutional rights and freedom of the nation". (84)

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (85)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (86)

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks". (87)

Stanley Baldwin made several broadcasts on the BBC. Baldwin "had recognized the importance of the new medium from its inception... now, with an expert blend of friendliness and firmness, he repeated that the strike had first to be called off before negotiations could resume, but repudiated the suggestion that the Government was fighting to lower the standard of living of the miners or of any other section of the workers". (88)

In one broadcast Baldwin argued: "A solution is within the grasp of the nation the instant that the trade union leaders are willing to abandon the General Strike. I am a man of peace. I am longing and working for peace, but I will not surrender the safety and security of the British Constitution. You placed me in power eighteen months ago by the largest majority accorded to any party for many years. Have I done anything to forfeit that confidence? Cannot you trust me to ensure a square deal, to secure even justice between man and man?" (89)

By 12th May, 1926, most of the daily newspapers had resumed publication. The Daily Express reported that the "strike had a broken back" and it would be all over by the end of the week. (90) Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, was extremely hostile to the strike and all his newspapers reflected this view. The Daily Mirror stated that the "workers have been led to take part in this attempt to stab the nation in the back by a subtle appeal to the motives of idealism in them." (91) The Daily Mail claimed that the strike was one of "the worst forms of human tyranny". (92)

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (93)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (94)

Herbert Smith was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him." (95)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers. Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (96)

Stanley Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries." (97)

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. Cook appealed to the public to support them in the struggle against the Mine Owners Association: "We still continue, believing that the whole rank and file will help us all they can. We appeal for financial help wherever possible, and that comrades will still refuse to handle coal so that we may yet secure victory for the miners' wives and children who will live to thank the rank and file of the unions of Great Britain." (98)

On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government". (99)

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work." (100)

In October 1926 hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of November most miners had reported back to work. Will Paynter remained loyal to the strike although he knew they had no chance of winning. "The miners' lock-out dragged on through the months of 1926 and really was petering-out when the decision came to end it. We had fought on alone but in the end we had to accept defeat spelt out in further wage-cuts." (101)

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a pit again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty." (102)

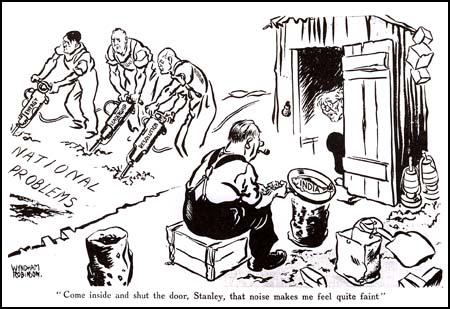

Neville Chamberlain wrote "Stanley Baldwin has suffered most from the strike; he too is worn out and has no spirit left." (103) It was claimed that Baldwin was on the edge of nervous collapse and felt he had to go on holiday to France. The national cost of nearly £100 million and a total loss of nearly £250 million had been incurred."Whole communities were alienated and impoverished; a large part of the nation was left with a feeling halfway between guilt and unease; and Baldwin's reputation as a statesman of sagacious moderation was badly dented." (104)

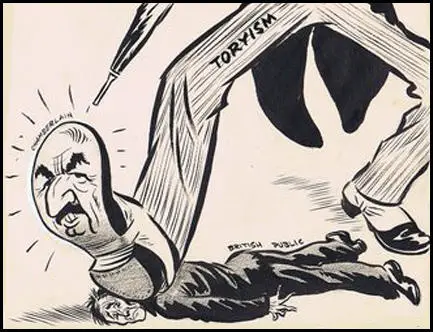

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men." (105)

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists." (106)

One of the results of this legislation was that trade union membership fell below the 5,000,000 mark for the first time since 1926. However, despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against the Conservative Party. Over the next three years the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. Stanley Baldwin considered offering government help to relieving distress in high unemployment areas but Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, insisted that "we must harden our hearts". (107)

In November 1926 Baldwin appointed John C. Davidson as chairman of the Conservative Party organization. "Davidson's period as party chairman was the most important and visible phase of his career. Although there were difficulties, his tenure is considered to have been one of the most significant in the development of the Conservative electoral machine in the twentieth century - a period in which it had been an important factor in the party's success.... He made a significant contribution in three main areas: rationalizing the basic structure, developing new areas, and expanding the scale of operations." (107a)

Stanley Baldwin and Davidson wanted to change the image of the Conservative Party to make it appear a less right-wing organisation. In March 1927 He suggested to his Cabinet that the government should propose legislation for the enfranchisement of nearly five million women between the ages of twenty-one and thirty. This measure meant that women would constitute almost 53% of the British electorate. The Daily Mail complained that these impressionable young females would be easily manipulated by the Labour Party. (108)

Churchill was totally opposed to the move and argued that the affairs of the country ought not be put into the hands of a female majority. In order to avoid giving the vote to all adults he proposed that the vote be taken away from all men between twenty-one and thirty. He lost the argument and in Cabinet and asked for a formal note of dissent to be entered in the minutes. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. (109)

There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. Many of the women who had fought for this right were now dead including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pankhurst. Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS during the campaign for the vote, was still alive and had the pleasure of attending Parliament to see the vote take place. That night she wrote in her diary that it was almost exactly 61 years ago since she heard John Stuart Mill introduce his suffrage amendment to the Reform Bill on May 20th, 1867." (110)

Davidson was determined to concentrate his future political campaigns to gain the support of women voters. He employed Marjorie Maxse, as Deputy Chief Agent, to make it quite clear to the Party that the women were to play a "very important part in the development of Conservatism in the country". (72) It has been pointed out by Neal R. McCrillis, the author of The British Conservative Party in the Age of Universal Suffrage (1998), that she told party agents "to teach women to be voters and Conservative voters, not to create a feminist movement within the Conservative party". (110a)

According to her biographer, Mark Pottle Marjorie Maxse believed that "women Conservatives were important for fund-raising and canvassing, and... she believed that men mostly did not wish to give them organizational responsibility and so she favoured developing separate women's branches at the constituency level... By retaining a separate organization women stood a greater chance to gain recognition of their role, as well as retain a degree of autonomy. She appreciated that this could also lead to their being marginalized, but on balance she felt that the policy brought about real advances." (110b)

Another important woman in Davidson's campaign was Caroline Bridgeman (the first woman to be Chairman of the Annual Conference). Davidson wrote to Sir Charles Hall-Cain about the good work that Bridgeman was doing: "When I think of the sacrifice that some of our women have made and the incalculable services they have given to the Party - women like Lady Bridgeman - it is not surprising that I am moved to cheer them on to further efforts... Whether we like it or not, the future of the country is largely in the hands of the women, equally with us men, and no greater service can be rendered to the Party than to provide as powerful a centre as possible in London for the attraction and education of Conservative women." (110c)

Baldwin firmly believed that he would win the 1929 General Election. He realised that he did not have a good manifesto, "but thought that his reputation as a moderate statesman, calmly if slowly steering the country in the right direction, would overcome that". (111) In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (112)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (113)

In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. The Conservatives lost 150 seats and became for the first time a smaller parliamentary party than Labour. David Lloyd George, the leader of the Liberals, admitted that his campaign had been unsuccessful but claimed he held the balance of power: "It would be silly to pretend that we have realised our expectations. It looks for the moment as if we still hold the balance." However, both Baldwin and MacDonald refused to form a coalition government with Lloyd George. Baldwin resigned and once again MacDonald agreed to form a minority government. (114)

Winston Churchill was furious with both David Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin that they had allowed this to happen. Lloyd George argued that he had no choice but to do this as his manifesto promises were much closer to the policies of the Labour Party. Churchill replied: "Never mind, you have done your best, and if Britain alone among modern States chooses to cast away her rights, her interests and her strength, she must learn by bitter experience." (115)

John C. Davidson was attacked by some members for his role in the general election campaign. "I have often been heavily criticized for concentrating the attack of the campaign on the Liberals rather than on the Socialists. There is a certain amount of justification in this criticism, but the reason we attacked the Liberals heavily was because they had a far greater nuisance value than they really deserved. They had no policy, they had - so far as one could tell - no political principles differing from ours, and yet they were determined to split the vote in order to get Labour in." (115a)

Davidson told Samuel Hoare that being chairman of the Conservative Party was a "thankless task" and "a blind alley" (115b) Neville Chamberlain led the attacks on Davidson and criticised the uninspiring campaign themes of "Safety first" and "Trust Baldwin". Davidson had alienated a range of figures, including the two main press barons, Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook. Rothermere that Baldwin did badly in the election because he was too left-wing and probably a "crypto-socialist". Chamberlain told Davidson bluntly in April that he had to go; after further delay, Chamberlain pressed again and Davidson resigned on 29th May, 1930. (115c)

United Empire Party

Lord Rothermere believed that Stanley Baldwin did badly in the election because he was too left-wing and probably a "crypto-socialist". Rothermere was especially concerned about the government's attitude towards the British Empire. Rothermere agreed with Brendan Bracken when he wrote: "This wretched Government, with the aid of the Liberals and some eminent Tories, is about to commit us to one of the most fatal decisions in all our history, and there is practically no opposition to their policy". Bracken believed that with the support of the Rothermere and the Beaverbrook newspaper empires it would be possible "to preserve the essentials of British rule in India". (116)

Lord Beaverbrook agreed and as he explained to Robert Borden, the former Canadian prime minister: "The Government is trying to unite Mohammedan and Hindu. It will never succeed. There will be no amalgamation between these two. There is only one way to govern India. And that is the way laid down by the ancient Romans - was it the Gracchi, or was it Romulus, or was it one of the Emperors? - that is Divide and Rule". (117)

Rothermere agreed to join forces with Beaverbrook, in order to remove Baldwin from the leadership of the Tory Party. According to one source: "Rothermere's feelings amounted to hatred. He had backed Baldwin strongly in 1924, and his subsequent disenchantment was thought to be connected with Baldwin's unaccountable failure to reward him with an earldom and his son Esmond, an MP, with a post in the government. By 1929 Rothermere, a man of pessimistic temperament, had come to believe that with the socialists in power the world was nearing its end; and Baldwin was doing nothing to save it. He was especially disturbed by the independence movement in India, to which he thought both the government and Baldwin were almost criminally indulgent." (118)

Rothermere and Beaverbrook believed the best way to undermine Baldwin was to campaign on the policy of giving countries within the British Empire preferential trade terms. Beaverbrook began the campaign on 5th December, 1929, when he announced the establishment of the Empire Free Trade movement. On the 10th December, the Daily Express front page had the banner headlines: "JOIN THE EMPIRE CRUSADE TODAY" and called on its readers to register as supporters. It also proclaimed that "the great body of feeling in the country which is behind the new movement must be crystallised in effective form". The appeal for "recruits" was repeated in Beaverbrook's other newspapers such as the Evening Standard and the Sunday Express. All his newspapers told those who had already registered their support to "enroll your friends... we are an army with a great task before us." (119)

In January, 1930, Rothermere's newspapers came out in support of Empire Free Trade. George Ward Price, a faithful Rothermere mouthpiece, wrote in the Sunday Dispatch, that "no man living in this country today with more likelihood of succeeding to the Premiership of Great Britain than Lord Beaverbrook". (120) The Daily Mail also called on Baldwin to resign and be replaced the press baron. Beaverbrook responded by describing Rothermere as "the greatest trustee of public opinion we have seen in the history of journalism." (121)

Beaverbrook wrote to Sir Rennell Rodd explaining why he had joined forces with Rothermere to remove Baldwin: "I hope you will not be prejudiced about Rothermere. He is a very fine man. I wish I had his good points. It (working with Rothermere) would make the Crusade more popular among the aristocracy - the real enemies in the Conservative Party... It is time these people were being swept out of their preferred positions in public life and their sons and grandsons being sent to work like those of other people." (122)

Rothermere now joined the campaign of Empire Free Trade: "British manufacturers and British work people are turning out the best goods to be bought in the world. They are far ahead of their competitors in two of the most important factors - quality and durability. The achievement of our industrialists and workers in the more impressive because they are handicapped in so many ways. Whereas in foreign countries politicians are considerate of industry and do all that is in their power to aid it, here the politicians will not even condescend to tell those few trades which have some slight vestige of tariff protection whether that protection is going to be continued or abolished." (123)

Beaverbrook had a meeting with Baldwin about the Conservative Party adopting his policy of Empire Free Trade. Baldwin rejected the idea as it would mean taxes on non-Empire imports. Robert Bruce Lockhart, who worked for Lord Beaverbrook, wrote in his diary: "In evening saw Lord Beaverbrook who will announced his New Party on Monday, provided Rothermere comes out in favour of food taxes. It is a big venture." Beaverbrook's plan was to run candidates at by-elections and general elections. This "would wreck the prospects of many Tory candidates, thus destroying Baldwin's hopes of a majority in the next Parliament". (124)

On 18th February, 1930, Beaverbrook announced the formation of the United Empire Party. The following day Lord Rothermere gave his full support to the party. A small group of businessmen, including Beaverbrook and Rothermere, donated a total of £40,000 to help fund the party. The Daily Express also asked its readers to send in money and in return promised to publish their names in the newspaper. Beaverbrook presented Conservative MPs with an implied ultimatum: "No MP espousing the cause of Empire Free Trade will be opposed by a United Empire candidate. Instead, he shall have, if he desires it, our full support. If the Conservatives split, they will do so because at last the true spirit of Conservatism has a chance to find expression." (125)

In the Daily Mail Rothermere ran stories about the new party on the front page for ten days in succession. According to the authors of Beaverbrook: A Life (1992): "With their combined total of eight national papers, and Rothermere's chain of provincial papers, the press barons were laying down a joint barrage scarcely paralleled in newspaper history." Rothermere told Beaverbrook that "this movement is like a prairie fire". Leo Amery described Beaverbrook "bubbling over with excitement and triumph". (126)

Beaverbrook later admitted that as a press baron he had the right to bully the politician into pursuing courses he would not otherwise adopt. (127) Baldwin was badly shaken by these events and in March 1930 he agreed to a referendum on food taxes, and a detailed discussion of the issue at an imperial conference after the next election. This was not good enough for Rothermere and Beaverbrook and they decided to back candidates in by-elections who challenged the official Conservative line. (128)

Ernest Spero, the Labour MP, for West Fulham, was declared bankrupt and was forced to resign. Cyril Cobb, the Conservative Party candidate in the by-election, declared that he supported Empire Free Trade and this gave him the support of the newspapers owned by Rothermere and Beaverbrook. On 6th May, 1930, Cobb beat the Labour candidate, John Banfield, with a 3.5% swing. The Daily Express presented it as a win for Beaverbrook, with the headline: "CRUSADER CAPTURES SOCIALIST SEAT". (129)