Punch Magazine

One evening at the beginning of June, 1841, Mark Lemon and Henry Mayhew, met at the Edinburgh Castle public house in the Strand, London, to discuss the possibility of starting a new journal. Lemon and Mayhew were both reforming liberals and the plan was to combine humour and political comment. Others invited to the original meeting included Douglas Jerrold, a journalist with the reputation for campaigning against poverty, and John Leech, a medical student whose drawings had impressed Lemon. During the meeting at the Edinburgh Castle, someone remarked that a humourous magazine, like good punch, needed lemon. Mayhew, remarked "A capital idea! Let's call the paper Punch."

Mark Lemon and Henry Mayhew found three other men to help finance the magazine, the printer, Joseph Last, the engraver, Ebenezer Landells and the businessman, Stirling Coyne. Lemon and Mayhew recruited a team of young journalists and artists. Douglas Jerrold was probably the most important journalist on the magazine, but other writers who contributed included Shirley Brooks, William Wills and William Makepeace Thackeray. As well as John Leech, who was with the magazine from the start, Richard Doyle and Archibald Henning produced the drawings.

1849. The cover was designed by Richard Doyle

The first edition of Punch Magazine was printed by Joseph Last of Fleet Street and published on Saturday, 17th July 1841. In an article entitled The Moral of Punch, Mark Lemon wrote that he hoped the journal would help, "destroy the principle of evil by increasing the means of cultivating the good". For the first few years of its existence, the magazine developed a reputation as "a defender of the oppressed and a radical scourge of all authority". Early targets included the monarchy and leading politicians. The magazine campaigned against the high cost of the monarchy. It pointed out that Prince Albert had a yearly allowance of £30,000, whereas the total amount spent on educating the poor in England was only £10,000.

The prime minister, Sir Robert Peel, also came under attack for the unfair taxes he had introduced and was often referred to as "Sir Rhubarb Pill, M.P., M.D., the new state physician." Other politicians who suffered from the caustic wit of Punch Magazine included Henry Brougham, Benjamin Disraeli and Daniel O'Connell. Politicians were seen as corrupt and self-seeking and only Radicals such as Joseph Hume were treated with respect.

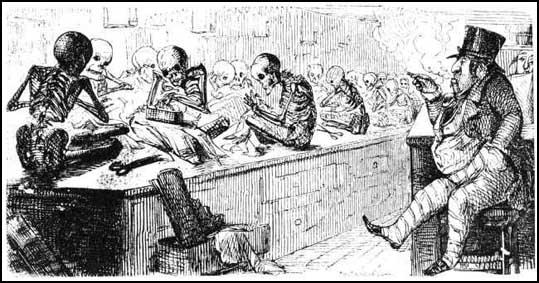

Employers who treated their workers badly were also condemned. In 1843 Punch Magazine published Thomas Hood's poem, The Song of the Shirt. This powerful indictment of capitalism was supported by cartoons such as Capital and Labour and Cheap Clothing, by John Leech, that illustrated the growth of inequality that was taking place in Britain during the 1840s. The magazine also campaigned against the Corn Laws, the 1834 Poor Law and reform of parliament. Although the magazine supported Moral Force Chartists it was totally opposed to those such as Feargus O'Connor who advocated the use of force to obtain the vote.

In the early years Punch Magazine sold about 6,000 copies a week. However, sales of 10,000 were needed to cover the costs of the venture. In December 1842 it was decided to sell the magazine to Bradbury & Evans. Mark Lemon was reappointed as editor and Henry Mayhew was given the role of "suggester-in-chief". Mayhew wrote his last article for the magazine in February, 1845 and over the next few months worked on his railway magazine, Iron Times.

The loss of Mayhew reduced the radical content of the magazine. Douglas Jerrold, complained to Lemon about the influence of conservative writers such as William Makepeace Thackeray. Jerrold continued to work for the magazine, but in 1850, Richard Doyle left in protest at what he saw as an anti-Catholic campaign.

The publishers believed that the radicalism of Punch Magazine was not popular with the majority of its readers. It was also argued that magazine's original readers had changed. As one writer pointed out: "Adolescents had become mature men who no longer trailed radical clouds of glory from their youth: they were by then established in their careers and involved in their domestic life and their growing number of children."Although there were some campaigns that Mark Lemon did support, such as a reduction in the hours of shopworkers, after 1850, the magazine reflected the conservative views of the growing middle class in Britain.

John Tenniel had some cartoons accepted by Punch Magazine and one showing Lord John Russell as David with his sword of truth attacking Cardinal Wiseman, as the Roman Catholic Goliath, upset Richard Doyle so much that he left the magazine. Mark Lemon, the editor, decided to replace Doyle with Tenniel and in December, 1850, he became a staff cartoonist with Punch. At first Tenniel was reluctant to take the post arguing that he was more concerned with "High Art". He also doubted his ability to produce humourous cartoons. He asked one friend: "Do they suppose that there is anything funny about me?"

John Tenniel gradually took over from John Leech as the producer of the main political cartoon in the magazine. Tenniel was a Tory and some of his cartoons upset radicals on the staff such as Douglas Jerrold. Tenniel denied being political prejudice and claimed that "if I have my own little politics, I keep them to myself, and profess only those of the paper".

Lewis Perry Curtis has pointed out: "Despite their dignified quality some of Tenniel's cartoons partook of the dominant prejudices of the day. His depiction of Jews included such standard antisemitic features as the hooked nose and the dark, oily locks of the Shylock–Fagin variety... Tenniel also endowed some African chieftains or warriors with such racialized traits as thick lips and big bellies. But when it came to the Irish - especially Fenians or republican separatists wedded to physical force - he delighted in simianizing rebel Paddy. Indeed, his Fenian apemen rank among the fiercest images of political violence ever to appear in the serio-comic format. By means of low foreheads, pointed ears, snub noses, high upper lips, receding chins, prognathous jaws, and sharp fangs, he turned these agitators into Calibans or gorilla–guerrillas."

M. H. Spielmann has argued: "Sir John Tenniel had dignified the political cartoon into a classic composition, and has raised the art of politico-humourous draughtsmanship into the relative position of the lampoon to that of polished satire - swaying parties and peoples, too, and challenging comparison with the higher (at times it might almost be said the highest) efforts of literature in that direction." Other cartoonists who worked for Punch during this period included George du Maurier, Charles Keene, Harry Furniss, Linley Sambourne, Francis Carruthers Gould and Phil May

After Mark Lemon died in 1870 he was replaced by Shirley Brooks as editor. He was followed by Tom Taylor (1874-1880), F. C. Burnand (1880-1906), Owen Seamen (1906-1932), E. V. Knox (1932-1949), Cyril Bird (1949-1952) and Malcolm Muggeridge (1953-1957).

In the 20th century Punch Magazine employed Britain's top cartoonists including F. H. Townsend, Frank Reynolds, Bernard Partridge, Alexander Boyd, Sidney Sime, Henry M. Brock, Cyril Bird, H. M. Bateman, Jack B. Yeats, Leonard Raven-Hill, George Stampa, Frederick Pegram, Lewis Baumer, George Belcher, George Morrow, Edmund Sullivan, Bert Thomas, James Dowd, F. G. Lewin, A. Wallis Mills, David Low and Leslie Illingworth.

During the 1980s the circulation of Punch dropped dramatically. The owners, United Newspapers, closed the magazine in 1992. In 1996 Mohamed Al Fayed re-launched the magazine. The venture was unsuccessful and Punch ceased publication in June 2002.

Primary Sources

(1) Douglas Jerrold, letter to Charles Dickens in 1846.

Punch, I believe, holds its course. Nevertheless, I do not very cordially I am convinced that the world will get tired (at least I hope so) of this eternal guffaw at all things. After all, life has something serious in it. It cannot be all a comic history of humanity. Unless Punch gets a little back to his original gravities, he'll be sure to suffer.

(2) George Julian Harney, letter to Friedrich Engels about Punch Magazine.

Punch contains a good deal of Free Trade and glorification of the Anti-Corn League. It dismisses as a mischievous delusion the doctrine of perfect equality. Instead it is for various "social improvements", "shorter hours", "sanitary reforms", "small farms", "perpetual leases", etc.

(3) Henry Hamilton Fyfe, My Seven Selves (1935)

I was a close student of the bound volumes of Punch that were in my school library. They went back to the beginning, and I got from them what was of great use to me - an idea of the history of the Victorian Age. Schoolbook histories left off far earlier. But for Punch's cartoons I should have known nothing about the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the fight for Free Trade, the No Popery campaign; nothing about the conspicuous personalities. Not only did Gladstone and Disraeli become real to me; I was familiar with funny little Lord John Russell, Palmerston sucking his straw, John Bright in his broad-brimmed Quaker hat.

As a social historian, he is unrivalled. His volumes show with unquestioned accuracy the changing costumes, customs, fads, fears, follies, of more than a hundred years. They provide a week by week record of everyday life, casting a wide net and gathering into it all sorts and conditions. Whenever Punch has during my lifetime shown strong bias, he has been usually on the side I consider wrong, but a chronicler I discovered, at the age of thirteen, his unique value, and have been grateful for it ever since.

(4) David Low, Autobiography (1956)

A pile of old copies of copies of Punch I found in the back room of a fatherly second-hand bookseller introduced me to the treasure of Charles Keene, Linley Sambourne, Randolph Caldecott and Dana Gibson. The more I poured over the intricate technical quality of these artists the more difficult did drawing appear. How impossible that one could ever become an artist! But then I came on Phil May, who combined quality with apparent facility. Once having discovered Phil May I never let him go.