Leslie Illingworth

Leslie Illingworth was born in Barry, South Wales, on 2nd September, 1902. His father, Frederick Illingworth (1899-1956), worked as a clerk in the engineers' department of the Barry Railway & Docks Company. His mother, Helen MacGregor Illingworth (1874-1952) was a former teacher.

Illingworth was educated at Palmerston Road Infants School, in the village of Cadoxton. In 1912 the family moved to Gileston and Illingworth continued his education at St Athan School. It was during this period he became interested in drawing. A family friend, George Jenkins, allowed him to copy cartoons from his collection of bound volumes of Punch Magazine. He was especially impressed with the drawings of Bert Thomas.

In 1917 Illingworth won a scholarship to study at the Cardiff Art School. A successful student, he won a gold medal for drawing and had four topical cartoons published in the college's magazine, Pen and Pencil. Illingworth studied in the morning and worked in the lithographic departments of the Western Mail. This involved producing police court drawings. He was also responsible for the regular football cartoon that appeared in the Football Express, the newspaper's Saturday night supplement.

In 1921 Illingworth won a three-year scholarship to the Slade Art School. Fellow students included Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden, Raymond Coxon, John Gilroy and Charles Tunnicliffe. He studied under Henry Tonks, who had been an official war artist in the First World War.

Illingworth continued to work for the Football Express and on 11th October 1921, his first political cartoon appeared in the Western Mail. After the death of J. M. Staniforth, Illingworth became the newspaper's main political cartoonist. Illingworth also worked as a free-lance cartoonists producing drawings for Strand Magazine, London Life, Answers to Correspondents and Tit-Bits.

Although his parents were supporters of the Conservative Party, Illingworth was a socialist who had read the works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. During the 1926 General Strike he produced his own plates when the print department of the the art department of the Western Mail refused to make them. Later he developed political views that were similar to those of the newspaper. He admitted: "I knew very well what the politics of the paper were, and I knew which side of my bread was buttered. The cartoonist must have a pragmatic approach."

Illingworth left the Western Mail in 1927. He moved to Paris for a year before moving to New Jersey. He now provided drawings for American magazines such as Life and Good Housekeeping. His first cartoon for Punch Magazine was published on 27th May 1931. He shared responsibility for producing the main political cartoon for the magazine with E. H. Shepard and Bernard Partridge.

On the outbreak of the Second World War he was offered £650 a year to become an official war artist. He refused the offer and instead accepted a job with the Daily Mail, that paid £2,000 a year. Illingworth later commented: "Being a cartoonist is the only job for me... It's like being on the admiral's bridge: you know what's going on and you're in the middle of it." He said his job during the war was easy: "We were against Hitler, against Mussolini, against Stalin to start with and then for him immediately as soon as he came in."

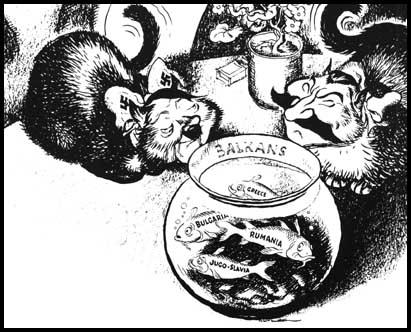

goldfish!" Daily Mail (17th November, 1940)

Illingworth drew four cartoons a week for the Daily Mail (normally published on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday). Illingworth's drawings continued to appear throughout the war, despite the fact that by the end of 1940 paper rationing had reduced the newspaper to six pages. As Mark Bryant has pointed out: "The resulting premium on space meant that other pictorial features - such as children's cartoons, continuity strips and sports cartoons - were later dropped. However, Illingworth's cartoon remained, a testament to its importance." During the Second World War Illingworth produced a total of 1018 cartoons for the newspaper.

Illingworth also produced the main political cartoon for Punch Magazine. Whereas his Daily Mail cartoons took four hours to complete, Illingworth usually liked to spend a whole day on the drawing that appeared in the weekly magazine. He later remarked: "I've never been told what to do. Never, never, never. The best editor is a man that will look at your roughs and say Oh, wonderful! Good! That's the one I want."

During the war Illingworth produced several propaganda posters for Alfred Duff Cooper and Harold Nicolson at the Ministry of Information. This included a series to encourage the public to speed up the loading and unloading of goods. He also produced cartoons for the De Vliehende Hollander newspaper that was dropped by the Royal Air Force over occupied Holland.

On the death of Bernard Partridge in 1945 Illingworth became the main political cartoonist on Punch Magazine. According to its editor, Malcolm Muggeridge (1953-57), Illingworth was "an incomparable black-and-white artist". The magazine's art editor, William Hewison described him as having a "faultless pen-and-ink technique, a technique which is essentially naturalistic yet masterly in its variety of textures, arrangement of tones, and subtle atmospheric perspective." Michael Cummings, the political cartoonist of The Daily Express, claimed that Illingworth's work was even better than that of John Tenniel.

Illingworth remained at the Daily Mail for twenty-nine years where he developed an impressive team of cartoonists that included Ralph Steadman and Wally Fawkes. In the 1960s he also illustrated his own international travel articles that appeared in the newspaper. In 1962 he was voted "Political and Social Cartoonist of the Year by the Cartoonists' Club of Great Britain.

On 22nd December, 1969, Illingworth published his last cartoon for the Daily Mail and retired to his smallholding in Robertsbridge, East Sussex. However, he continued to work as a guest political cartoonist on the News of the World. In 1975 he was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Kent, home of the British Cartoon Archive.

Leslie Illingworth died in Hastings Hospital on 20th December 1979, after suffering a stroke while having an operation for gallstones.

Primary Sources

(1) Mark Bryant, Illingworth's War in Cartoons (2009)

In 1921 Illingworth won a three-year scholarship (worth £90 a year) to study in London under Sir William Rothenstein at the Royal College of Art, then based in Exhibition Road, South Kensington... Though by this time living in London at 3 Battersea Bridge Road West, Illingworth continued to draw his weekly cartoons for the Football Express. Then when the 58-year-old Staniforth became ill, Illingworth's father - who played golf with the Western Mail's managing director Robert J. Webber (Dick Illingworth was a founder member and later secretary of the club) - suggested that his son should be Staniforth's understudy. His first political cartoon appeared in the paper on Tuesday 11 October 1921, signed "L.C.Illingworth".

J.M. Staniforth died on 17 December 1921, earning personal tributes from the Welsh-born Prime Minister Lloyd George (prime minister from 1916 to 1922) amongst other celebrities. As a result, Illingworth took over his job and began to work on the paper (three months after his 19th birthday), then edited by Sir William Davies, for £6 a week.

For a while Illingworth continued to study and live in London but by the time he was 20 he was earning the then high sum of £1000 a year from the Western Mail and other work (his father, who had a senior and responsible job in charge of 300 clerks, had only been earning c. 1360 p.a. in 1920). As a result he decided to give up his studies at the RCA and returned to Wales to live with his parents and sister in Gileston, cycling into Cardiff each day.

(2) Henry Fairlie, Daily Mail (1957)

He delights in observing people and it is this observation which accounts for the fact that, unlike almost every other cartoonist, lie does not rely on exaggeration in order to give his caricatures of public figures their point and their impact. He has had the insight to see that everyone is such a caricature of himself in himself that there is no need, if he is acutely observed, to exaggerate.

(3) Malcolm Muggeridge, Vicky's World (1959)

A satirist, by the nature of the case, cannot but give offence. Truth is his medium, and truth hurts. If he muffles or evades it, he ceases to be a satirist - which is why he is a dangerous instrument of propaganda, and a poor servant of conformity An untruthful satirist is as inconceivable as a colour-blind artist or a tone-deaf musician. This is particularly true of the graphic satirist, of the caricaturist or cartoonist. He has to crystallize a moment of bitter awareness of man's inhumanity, greed, hypocrisy, futility... On the other hand, the graphic satirist has his reward. It is in his power to capture, in a way which is possible in no other medium, the fleeting, dancing particles of history. Words which belong to the moment for the most part perish with the moment.

(4) Keith Mackenzie, The Artist (1969)

Leslie Gilbert Illingworth could be described as the last of the great penmen in the line of English social satirists starting with Hogarth and traceable through the biting and rambunctious broadsides of Rowlandson, Gillray and Cruikshank to the more moderate social comments of Leech, 'Tenniel, Keene and Phil May...it is fairly safe to assume that when the history of cartoon and caricature comes to be written the name of Illingworth will have a valued place in the tradition of great political satire of this century, along with Will Dyson, Low. Giles. Vic ky and Osbert Lancaster... He is not a cruel or violent man, nor does he do violence to his subjects. His caricatures (are) done with the minimum of distortion, penetrating, delving into the heart and soul - the skull beneath the skin which sets the satirist apart from the cartoonist....

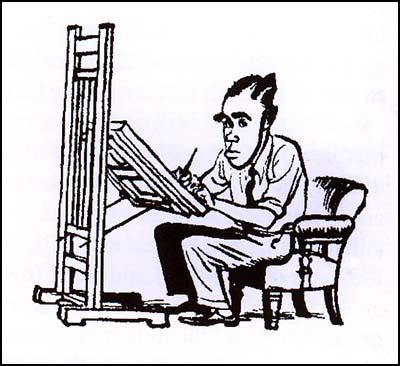

Illingworth's day starts when he listens to the early morning's news and studies all the morning's papers. By the time he arrives at Northcliffe House several possibilities are taking shape in his head. Before lunch a number of linear roughs are presented to the editor and the chosen idea and appropriate shape decided upon. With a roughly pencilled design on a virgin sheet of board, the real work starts after lunch when the situation, likeness and background will be rapidly drawn in with a fine pen, strengthened by brush, chalk, mechanical tint or wash. He doesn't use photographic reference much; like all good draughtsmen he draws things well because he "knows" them.

(5) Malcolm Muggeridge, The Guardian (22nd December 1979)

I think myself that a collection of his best cartoons will, in the long run, wear better than one of David Low's: the reason being that Low's cartoons usually relate to some immediate situation which soon gets forgotten, whereas Illingworth's go deeper, becoming, at their best, satire in the grand style rather than mischievous quips: strategic rather than practical.