Henry Tonks

Henry Tonks, the fifth among the eleven children of Edmund Tonks and his wife, Julia Johnson, was born in Solihull on 9th April 1862. His father owned a brass foundry in Birmingham.

Tonks attended Clifton College (1877-1880) and then studied medicine at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. In 1887 he was the house surgeon of Frederick Treves and the following year was appointed as senior medical officer at the Royal Free Hospital. In 1892 he became a teacher of anatomy at the London Hospital Medical School.

In his spare time he attended drawing lessons at the Westminster School of Art. After his teacher, Frederick Brown, became principal of Slade Art School, he convinced Tonks to give up medicine and become one of its teachers. According to his biographer, Lynda Morris: "Tonks used his anatomical knowledge to teach life drawing as a swift and intelligent activity. He referred his students to old master drawings at the British Museum and taught his pupils to draw the model at the size it was seen, measured at arm's length (sight size), which enabled them continually to correct the drawing for themselves, against a physical object."

A friend, the novelist, George Moore, later recalled: "He read everything that was written about drawing; he listened to all that his friends had to say; he thought about drawing, and he practised drawing, praying that the secret might be vouchsafed to him, for art has become Tonks's religion." One of his students described Tonks as a "towering, dominating figure, well over six feet tall, lean and ascetic looking, with large, hooded eyes, a nose dropping vertically from the bridge like an eagle's beak and a quivering, camel-like mouth. There was about him an aura of incorruptible nobility of purpose and he was... respected by all the students and feared by many."

Gilbert Spencer, the brother of Stanley Spencer, was another of his students. He later wrote how Tonks "talked of dedication, the privilege of being an artist, that to do a bad drawing was like living with a lie, and he proceeded to implant these ideals by ruthless and withering criticism. I remember once coming home and feeling like flinging myself under a train, and Stan telling me not to mind as he did it to everyone."

Tonks later admitted: "I certainly cannot draw, though I have a passion for drawing; I am uncertain about the direction of lines; I have no skill of hand, and to express myself at all I have the greatest difficulty. Perhaps it is that being so deficient myself, I have enough honesty to urge my students to strengthen themselves where I am weak."

Tonks developed a reputation for being very harsh with his students. Randolph Schwabe has argued: "Once I witnessed an odd scene. A new student had come into the Antique Room, a very tall, heavy man, in private life an amateur pugilist. He sat as others did on a low seat near the floor, doing his untutored best to render the cast in front of him. Tonks, from his great height, bent over him and said cuttingly - I suppose you think you can draw. The student collected himself, rose slowly to an even greater height than Tonks and, looking down, replied with suppressed fury (but perfect justice) - If I thought I could draw - I shouldn't come here, should I? He had the better of the encounter. Tonks had nothing to say, and left the room."

In the 1890s Tonks taught Augustus John, Gwen John, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore. However, it was the generation that he taught at the beginning of the century that really made a mark on the art world. This included C.R.W. Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, John Currie, Dora Carrington, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Dorothy Brett, Paul Nash, John Nash, David Bomberg, Isaac Rosenberg, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee. Nevinson commented that the Slade "was full with a crowd of men such as I have never seen before or since." He also wrote that Gertler was "the genius of the place... and the most serious, single-minded artist I have ever come across." Tonks recognised their talent but found them too rebellious and later commented: "What a brood I have raised."

Tonks employed Roger Fry as one of the tutors at the Slade Art School. Fry took a keen interest in all forms of art. In May 1910 he wrote an article for The Burlington Magazine on drawings by African Bushman, where he praised their sharpness of perception and intelligence of design. David Boyd Haycock argued that "Fry was opening up his awareness to a wider sphere of artistic expression, though it was not one that would win him many friends." Henry Tonks remarked to a friend: "Don't you think Fry might find something more interesting to write about than Bushmen." Tonks was also highly critical of Cubism. Tonks declared: "I cannot teach what I don't believe in. I shall resign if this talk about Cubism does not cease; it is killing me." This attitude increased the view that he had become a reactionary.

Later that year Roger Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy went to Paris and after visiting "Parisian dealers and private collectors, arranging an assortment of paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries" in Mayfair. This included a selection of paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, André Derain and Vincent Van Gogh. As the author of Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Although some of these paintings were already twenty or even thirty years old - and four of the five major artists represented were dead - they were new to most Londoners." This exhibition had a marked impression on the work of Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Spencer Gore.

Henry Tonks told his students that although he could not prevent them visiting the Grafton Galleries, he could tell them "how very much better pleased he would be if we did not risk contamination but stayed away". His views were shared by most of the art world. The critic for The Pall Mall Gazette described the paintings as the "output of a lunatic asylum". Robert Ross of The Morning Post agreed claiming the "emotions of these painters... are of no interest except to the student of pathology and the specialist in abnormality". These comments were especially hurtful to Fry as his wife had recently been committed to an institution suffering from schizophrenia. Paul Nash recalled that he saw Claude Phillips, the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, on leaving the exhibition, "threw down his catalogue upon the threshold of the Grafton Galleries and stamped on it."

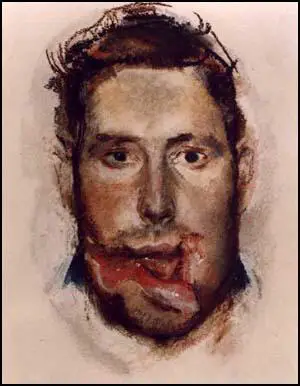

On the outbreak of the First World War, Tonks returned to medicine and joined the Royal Army Military Corps on the Western Front. In 1915 he worked as an orderly near the Marne and with a British ambulance unit, organized by the historian G. M. Trevelyan. In 1916 he was commissioned lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps and began visiting the unit being run by Harold Gillies at Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. As a doctor and artist, he was selected to join the team pioneering plastic surgery. His role was to make pastel drawings of facial war wounds. The unit proved inadequate and a new hospital devoted to facial repairs was developed at Sidcup.

Tonks was appointed principal of the Slade Art School in 1917. In 1918 Tonks and John Singer Sargent were both invited to become official war artists. They both witnessed men being treated for blindness after a mustard gas attack. Whereas Sargent painted Gassed, Tonks produced An Advanced Dressing Station in France. Tonks also completed another painting with a medical theme while on the Western Front, An Underground Casualty Clearing Station (1918).

Frederick Brown retired in 1918 and Tonks was offered the Slade professorship. The next generation of students included Thomas Monnington, William Coldstream, Helen Lessore and Philip Evergood. Lessore later recalled that Tonks "was a towering, dominating figure, about 6ft. 4in. tall, lean and ascetic looking, with large ears, hooded eyes, a nose dropping vertically from the bridge like an eagle's beak and quivering camel-like mouth".

After the war Tonks returned to the Slade Art School. He continued to paint and his most well-known work, Saturday Night in the Vale, was completed just before his retirement in 1930. That year Sir Harold Gillies's book Plastic Surgery of the Face was published. Tonks realistic drawings created a great deal of controversy. The drawings were later acquired by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Tonks was offered a knighthood on his retirement in 1930, which he declined. He wrote articles for The Times, and continued to paint and was only the second living British artist to be honoured by a retrospective exhibition at the Tate Gallery, in 1936.

Henry Tonks died at his home in Chelsea, on 8th January 1937.

Primary Sources

(1) (1)Randolph Schwabe, The Burlington Magazine (January 1943)

Once I witnessed an odd scene. A new student had come into the Antique Room, a very tall, heavy man, in private life an amateur pugilist. He sat as others did on a low "donkey" near the floor, doing his untutored best to render the cast in front of him. Tonks, from his great height, bent over him and said cuttingly - "I suppose you think you can draw". The student collected himself, rose slowly to an even greater height than Tonks and, looking down, replied with suppressed fury (but perfect justice) - "If I thought I could draw - I shouldn't come here, should I?" He had the better of the encounter. Tonks had nothing to say, and left the room.

Another reminiscence which concerns Brown, Tonks and Steer, is of a woman student, who, in trepidation, took her work to Tonks for criticism. She went to the Professor's room. It was the... hour when no teaching was done in the classes. The Professor and his two associates were having tea. Tonks looked through her pictures with more than usually savage comments, which reached a point when the girl could scarcely restrain her tears. Brown could bear it no longer. He seized a picture, carried it to the light and remonstrated, - "But it isn't as bad as all that, Tonks!" Meanwhile the unfortunate victim felt a warm hand sympathetically squeezing hers. It was Steer's. Somehow she collected the pictures and got away.

(2) George Moore, Conversations in Ebury Street (1924)

He read everything that was written about drawing; he listened to all that his friends had to say; he thought about drawing, and he practised drawing, praying that the secret might be vouchsafed to him, for art has become Tonks's religion.

(3) Henry Tonks, Artwork (1929)

I certainly cannot draw, though I have a passion for drawing; I am uncertain about the direction of lines; I have no skill of hand, and to express myself at all I have the greatest difficulty. Perhaps it is that being so deficient myself, I have enough honesty to urge my students to strengthen themselves where I am weak.

(4) (4)David Boyd Haycock, A Crisis of Brilliance (2009)

Tonks's dedication and demeanour derived partly from insecurity (he was not a naturally gifted draughtsman), and partly from the roundabout route he took to becoming an artist - what he himself called "a strangely devious one". Born in Birmingham in 1862, he was the victim of an English public school: after nine years' education at Clifton, near Bristol, he left having learnt little. Though already in love with the idea of being an artist, he imagined these curious creatures somehow emerged fully formed and readily capable of producing masterpieces, "so my position seemed hopeless". Instead he decided to become a doctor. At a teaching hospital in Brighton he met a fellow student who shared his interest in art, and who encouraged him to practice. When Tonks moved on to a hospital in London he utilized his developing artistic talent by demonstrating at anatomy classes, and he drew the patients whenever he could. If patients were unavailable to model, he used cadavers instead, bribing the post-mortem porter to fix a corpse on a table for him, "which I could then draw at my ease."

Drawing gradually became Tonks's "absorbing passion": what he lacked in natural talent he made up for with dedication and practice. On ward rounds "each patient had a double interest, that of the disease which brought him there, and his possibilities as a model and how I would express them." He discovered another doctor with a similar interest and they found more curious methods of obtaining models. On free evenings they wandered the red light districts until they found a girl who interested them, and then accompanied her to her lodgings where they made their sketches as the girl posed nude. "This worked quite successfully," Tonks later recalled.

Tonks, like Gerder after him, was inspired to become an artist by reading the life of a Victorian artist, Randolph Caldecott, who progressed from a Manchester bank clerk to become an artist and illustrator in London. Thus in 1888, the same year he was appointed Senior Medical Officer at London's Royal Free Hospital, Tonks began studying part-time with Fred Brown at the Westminster Art School. Brown was so impressed by Tonks's draughtsmanship and dedication that when he was offered the Slade Professorship he invited Tonks to become his drawing master. Tonks's father "expressed his extreme displeasure" at his son taking the position and abandoning his medical career. But Tonks believed he owed to Brown "the great happiness of my life."