C.R.W Nevinson

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson, the son of Henry Nevinson, the radical journalist, and Margaret Nevinson, an activist in the campaign for women's rights, was born in Hampstead on 13th August 1889. Frank Rutter argued in Art in My Time (1935): "Nevinson was the child of parents who had singularly noble ideas, who were markedly progressive and humane in their habit of thought... Nevinson started life with a pre-natal tendency to revolt against injustice, cruelty and oppression." However, his parents' constant campaigning meant that he often felt ignored as a child. He later wrote: "If my mother does happen to be in for a meal she is so engrossed in other things that she hardly hears and certainly never takes in a word I say."

Nevinson was sent away to boarding school. He hated the experience and in his autobiography, Paint and Prejudice (1937) he recalled: "I went to a large school, a ghastly place from which I was rapidly removed as I had some sort of breakdown owing to being publicly flogged, at the age of seven, for giving away some stamps which I believed to be my own. I was not only described as a thief but as a fence. From this moment I developed a shyness which later on became almost a disease. During my sufferings under injustice a conflict was born in me, and my secret life began.

His parents developed a reputation for holding radical political opinions. On the outbreak of the Boer War they became unpopular with the local population. "I worked steadily and nothing much happened until the outbreak of war with the Boers, when my father was seen at pro-Boer meetings on Parliament Hill, at which all manner of cranks were present. Morris, the slum reformer, was one of them, and I think another was G. B. Shaw. Whether my father was present in his capacity as a journalist or as a pro-Boer made no difference to the young men of Hampstead. I became a pariah and several times was thrown into handy ponds by patriots."

On 9th September 1899, Henry Nevinson was sent to South Africa to cover the war. Nevinson reached the garrison town of Ladysmith on 5th October. Later that month he witnessed "Black Monday" when over 800 men were taken prisoner were taken after an engagement extending about fifteen miles from Nicholson's Nek. As the Boers launched no immediate assault, the British force reorganised and constructed defensive lines around the town. The Siege of Ladysmith lasted until 28th February 1900. Nevinson's account of the siege first appeared in The Daily Chronicle. Later that year Methuen published his Ladysmith: The Diary of a Siege.

In 1903 Nevinson was sent to Uppingham School. "I had no wish to go to any such school at all, but nevertheless Uppingham did seem to be the best. Since then I have often wondered what the worst was like. No qualms of mine gave me an inkling of the horrors I was to undergo. Bad feeding, adolescence - always a dangerous period for the male - and the brutality and bestiality in the dormitories, made life a hell on earth. An apathy settled on me. I withered. I learned nothing. I did nothing. I was kicked, hounded, canned, flogged, hairbrushed, morning, noon and night. The more I suffered the less I cared."

After leaving Uppingham he went to the St John's Wood School of Art. "From Uppingham I went straight to heaven: to St. John's Wood School of Art, where I was to train for the Royal Academy Schools." He also began to have relationships with young women. The most important was Philippa Preston, but he eventually lost her to Maurice Elvey: "My shyness went, and I spent a good deal of my time with Philippa Preston, a lovely creature who was later to marry Maurice Elvey. There were others, blondes and brunettes. There were wild dances, student rags as they were called... and various excursions with exquisite students, young girls and earnest boys; shouting too much, laughing too often."

Nevinson met Ramsay MacDonald while he was visiting his mother. He noticed some of his drawings and suggested that he should consider producing some posters for the Labour Party. MacDonald introduced Nevinson to James Keir Hardie, who he described as "a man with a head like a lion". Nevinson submitted a design for a poster: "Naturally in this phase of artistic prejudice my poster for the Labour Party was a dismal affair: too black, too overworked, and the hands of the labourer were more Dürer than Dürer. It was rejected."

In 1909 he entered the Slade School. His first impressions were unfavourable: "Immediately I was aware again of that terrible disapproving atmosphere of the public school. Once more shyness and uncertainty came back to me." However, after a few months he made friends with a group of very talented students. This included Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, John Currie, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee. This group became known as the Coster Gang. According to David Boyd Haycock this was "because they mostly wore black jerseys, scarlet mufflers and black caps or hats like the costermongers who sold fruit and vegetables from carts in the street".

Nevinson commented that the Slade "was full with a crowd of men such as I have never seen before or since." Another student, Paul Nash, said that the "Slade... was in one of its periodical triumphal flows". One of their tutors, Henry Tonks, who found them too rebellious, later pondered: "What a brood I have raised." During this period Tonks told Nevinson he lacked the talent to become an artist.

In 1910 Dora Carrington joined the Slade School. According to Michael J. K. Walsh, the author of C. R. W. Nevinson: The Cult of Violence (2002): "Nevinson's infatuation with Dora Carrington became progressively more acute. In Carrington he had met his match, not only in intellect and in personality, but also in that she could be as obtuse as he could... The friendship was always confused, faltering between brotherly affection and unfulfilled love affair, rooted in Nevinson's reluctance to trust strangers and her notorious desire to remain unattached."

They spent a great deal of time together and they were also regular correspondents. Nevinson told Carrington in April 1912: "I have risen early in the morning before the day was dawning in order to await the post which comes about eight o'clock! I do not recall ever having been in such an exotic condition." Later that month: "I am flattered, I believe you really love me. If I should happen to be in a fools' paradise don't tell me. I infinitely prefer it to a wise man's purgatory."

While Nevinson was at the Slade School he was accused of making one of the life-models pregnant. In his autobiography he joked that it could have been any one of seventeen men, including his teacher, Tonks. When the child was born Tonks collected money for the women but Nevinson could not afford to make his contribution. He told Dora Carrington: "Tonks has been saying about me that he has never in all his life heard of any man behaving worse than I have done, he little knows how I loathe not being able to pay for my own misfortune (if it is mine) but as it is by the girl's particular wish not to tell my people I do not see how I can pay Tonks the beastly £10 or whatever it is he gave the girl."

Nevinson became a close friend of Mark Gertler. Gertler wrote to William Rothenstein: "My chief friend and pal is young Nevinson, a very, very nice chap. I am awfully fond of him. I am so happy when I am out with him. He invites me down to dinners and then we go on Hampstead Heath talking of the future." According to Michael J. K. Walsh: "Together they studied at the British Museum, met in the Café Royal, dined at the Nevinson household, went on short holidays and discussed art at length. Independently of each other too, they wrote of the value of their friendship and of the mutual respect they held for each other as artists."

Nevinson recorded in his autobiography, Paint and Prejudice (1937): "I am proud and glad to say that both my parents were extremely fond of him." Henry Nevinson recalled: "Gertler came to supper, very successful, with admirable naive stories of his behaviour in rich houses and at a dinner given him by a portrait club, how he asked to begin because he was hungry."

On 12th June 1912, Dora Carrington wrote to Nevinson. The letter has not survived, but his response to it has. It starts: "Your note came as a horrible surprise to me. I cannot guess what has happened to make you wish to do without me as a friend next term." It seems that Carrington had complained about the intimacy of his letters. He added: "I swear I will never speak a word to you as your lover... I promise you I will be a great friend of yours nothing more and nothing less and if you want to get simple again I am only too willing to do the same."

Carrington also received a letter from Mark Gertler asking her to marry him. When she rejected this proposal he wrote a further letter on 2nd July, suggesting: "Your affections are completely given to Nevinson. I must have been a fool to stand it as long as I have, without seeing through you. I have written to Nevinson telling him that we, he and I, are no longer friends." In the letter he argued, "much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends."

Nevinson continued to plead with Dora Carrington to remain his friend: "I am now without a friend in the whole world except you.... I cannot give you up, you have put a reason into my life and I am through you slowly winning back my self-respect. I did feel so useless so futile before I devoted my life to you." He also wanted a return of Gertler's friendship: "I am aching for the companionship of Gertler, our talks on Art, on my work, his work and our life in general. God how fond of him I am. I never realised it so thoroughly till now."

Mark Gertler now wrote to Nevinson: "I am writing here to tell you that our friendship must end from now, my sole reason being that I am in love with Carrington and I have reason to believe that you are so too. Therefore, much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends. You must know that ever since you brought Carrington to my studio my love for her has been steadily increasing. You might also remember that many times, when you asked me down to dinner. I refused to come. Jealously was the cause of it. Whenever you told me that you had been kissing her, you could have knocked me down with a feather, so faint was I. Whenever you saw me depressed of late, when we were all out together, it wasn't boredom as I pretended but love."

Nevinson left the Slade School in the summer of 1912 and travelled to Paris. There he met Gino Severini and Filippo Marinetti, two advocates of Futurism. Nevinson was impressed with their ideas and in June 1914 he joined forces with Marinetti to publish Vital English Art, a futurist manifesto. This created a great deal of controversy. The Times reported on 16th June, 1914: "Nevinson is a rebel in execution. He used to be a painter with a modest talent; but now he is like a singer with a small voice who has taken to shouting. Futurism, we are sure, is merely poison to him; and, if he has not lost his talent altogether, it will take him some time to recover it."

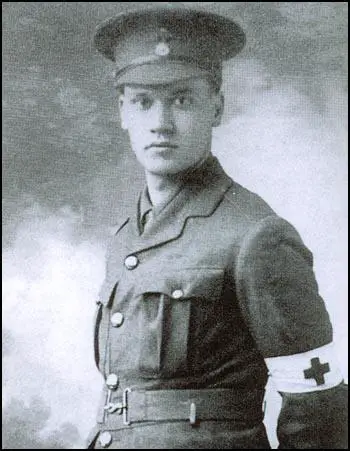

On the outbreak of the First World War, Nevinson, as a pacifist, refused to become involved in combat duties, and volunteered instead to work for the Red Cross. Sent to the Western Front in November 1914, Nevinson worked as a driver, stretcher-bearer and hospital orderly. He returned home in January 1915. The following month he wrote in The Daily Express: "All artists should go to the front to strengthen their art by a worship of physical and moral courage and a fearless desire of adventure, risk and daring and free themselves from the canker of professors, archaeologists, cicerones, antiquaries and beauty worshippers."

Nevinson argued that: "Our Futurist technique is the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe." This was reflected in his painting, Returning to the Trenches, that he had painted on the Western Front. The art critic, P. G. Konody wrote in The Sunday Observer on 14th March, 1915: "He has realised the uselessness of painting pictures that have no meaning for anybody but the artist himself, and therefore places his Futurist experiment on a lucid basis of realism. His Returning to the Trenches is really an uncommonly interesting picture, in which he has found an extremely expressive formula for the rhythmic marching of a body of French infantrymen fully armed and laden with all the paraphernalia for a prolonged stay in the trenches."

Nevinson was quoted in The Daily Graphic as saying that all artists in Britain should experience the fighting in the First World War: "I am firmly convinced that all artists should enlist and go to the front, no matter how little they owe England for her contempt of modern art, but to strengthen their art of physical and moral courage and a fearless desire of adventure, risk and daring."

Nevinson decided to join the Royal Army Medical Corps. On 1st November 1915, Nevinson married Kathleen Knowlman at Hampstead Town Hall. Margaret Nevinson recalled: "My son informed me, suddenly, one evening that, though not engaged, he meant to get married before he was killed." Instead of being sent to France he helped nurse soldiers being treated at the Third General Hospital in London. After contacting rheumatic fever in January, 1916, he was invalided out of the army. Nevinson later recalled: "I was now crippled completely. I began to think I should never walk again. Everything was tried on me while I lay helpless on my bed."

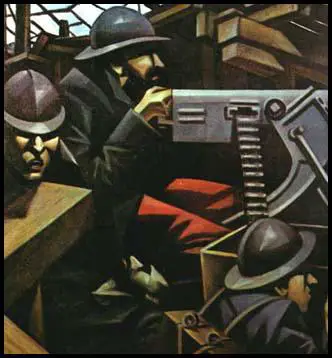

While recuperating, Nevinson painted a series of paintings based on his experiences in France. His first exhibition took place in March 1916. La Mitrailleuse, was much praised by the critics. Charles Lewis-Hind wrote: "You peer into a pit in the zone of fire; barbed wire stretches across the surface of the machinomorphic pit; above is the grey, clear sky of France. In the pit are four French soldiers. One lies dead. The three living men are conscious of one thing only - the control of their death-scattering mitrailleuse. There it lurks, rigid and venemous, ready to spit out immense destruction. And the gunners? Are they men? No! They have become machines. They are as rigid and as implacable as their terrible gun." Walter Sickert described it as "the most concentrated and authoritative utterance on war in the history of painting." Another critic wrote: "the hard lines of the machinery dictate those of the robotised soldiers who become as one with the killing machine." Another pointed out that: "the painting translates the mechanical aspect of modern warfare where man and machine combine to form a single force of nature".

Other war paintings by Nevinson include Paths of Glory, The Harvest of Battle, Marching Men, A Group of Soldiers, Troops Resting and The Road from Arras to Bapaume. Some critics dismissed his paintings as unrealistic. One soldier wrote to the Saturday Review and defended Nevinson's paintings: "Show them to any fellow who has inhabited a dug-out. Pass them round any mess in France or Flanders. Ask the man next to you in hospital in town what he thinks of them... I think you will find he has a pretty whole-hearted admiration for the art of the man who has realised it so wonderfully."

An exhibition of his work in September, 1916, brought him to the attention of Charles Masterman, head of the government's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB). In 1917 the WPB sent Nevinson to the Western Front where he painted another sixty pictures. Nevinson was unhappy with his work as a member of the WPB. He shared the feelings of Paul Nash who wrote at the time: "I am no longer an artist. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls."

Some of Nevinson's paintings such as Paths of Glory, were considered to be unacceptable and were not exhibited to after the Armistice. Nevinson wrote to Masterman: "My only instructions from you were to paint exactly what I wanted, as you knew my work would be valueless as an artist and propagandist otherwise."

Michael J. K. Walsh, the author of C. R. W. Nevinson: The Cult of Violence (2002) argued: "As the public lost their taste for the war theme, so would they lose their enthusiasm for Nevenson's art". The art critic, Frank Rutter, pointed out: "There is a danger that Mr Nevinson may have survived the war only for his art to be killed by his popularity."

Nevinson's wife gave birth to a son, Anthony Christopher Wynne on 21st May 1919. His mother, Margaret Nevinson, recorded that the child only lived for fifteen days, which had been "just enough time to get fond of him." Nevinson wrote in his autobiography: "On my arrival in London I was met by my mother, who told me my son was dead." He later added "I am glad I have not been responsible for bringing any human life into this world."

After the war he wrote regular articles for The Daily Mail, The Daily Express, The New Statesman, The Strand Magazine, and Harper's Bazaar. His biographer, Julian Freeman, pointed out: "From 1920 until 1940 they carried his strident, maverick diatribes, aimed at society at large, and at the establishment in all its forms... and the variety, salacity, and often uncompromising savagery of his egocentric articles remains enormously entertaining. However, his autobiography is marked and marred by a strong undercurrent of confrontational right-wing xenophobia, and some of his private correspondence in the Imperial War Museum in London is explicitly racist: true signs of the times to which he was such a conspicuous contributor."

Nevinson published his autobiography, Paint and Prejudice in 1937 and two years later was elected an ARA. Nevinson became a war artist in the Second World War but his career came to an end when he had a series of severe strokes in 1942 and 1943.

Christopher Nevinson died of heart disease on 7th October 1946 at his home, 1 Steeles Studios, Haverstock Hill, Hampstead.

Primary Sources

(1) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

In due time I went to a large school, a ghastly place from which I was rapidly removed as I had some sort of breakdown owing to being publicly flogged, at the age of seven, for giving away some stamps which I believed to be my own. I was not only described as a thief but as a fence. From this moment I developed a shyness which later on became almost a disease. During my sufferings under injustice a conflict was born in me, and my secret life began.

Shortly afterwards I was sent to University College, where I rapidly recovered from the immediate effects of this experience and became a normal, healthy child, quick at learning, with a passion for engineering, and a capacity for painting imaginary and historical subjects which were so far from bad that I was eventually given a prize by Professor Michael Sadler, representing the Board of Education.

(2) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

I worked steadily and nothing much happened until the outbreak of war with the Boers, when my father was seen at pro-Boer meetings on Parliament Hill, at which all manner of cranks were present. Morris, the slum reformer, was one of them, and I think another was G. B. Shaw. Whether my father was present in his capacity as a journalist or as a pro-Boer made no difference to the young men of Hampstead. I became a pariah and several times was thrown into handy ponds by patriots...

Fortunately my father soon left for South Africa as a war-correspondent and was besieged in Ladysmith. I got accustomed to seeing Nevinson in the newspapers and on the placards, and was grateful indeed that I could now walk alone without fear of further persecution of Kipling-minded Beggars.

(3) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

When Ladysmith was relieved, my father had returned on short leave before going to Pretoria, and there is no doubt he was impressed by the charm and brilliance of the Army staff, and the nobility and altruism that seemed to be founded on the public-school spirit. It was much later on in life that he became Socialist. In those days he was a polished Englishman of culture, and said he wanted me to go to Shrewsbury, his old school, and on to Balliol, if not into the Army itself.

Perceiving that I had little interest in the classics, but was enthralled by modern mechanics, and above all by the internal-combustion engine, my mother compromised and in my father's absence chose Uppingham. It was a great public school with the traditions of Tring, and it was more modern than other public schools of that time. Science was not merely regarded as "stinks", and music and painting were not looked upon as crimes. In fact, David, a German pupil of Richter, was almost head master owing to the importance in which music was held.

I had no wish to go to any such school at all, but nevertheless Uppingham did seem to be the best. Since then I have often wondered what the worst was like. No qualms of mine gave me an inkling of the horrors I was to undergo.

Bad feeding, adolescence - always a dangerous period for the male - and the brutality and bestiality in the dormitories, made life a hell on earth. An apathy settled on me. I withered. I learned nothing. I did nothing. I was kicked, hounded, canned, flogged, hairbrushed, morning, noon and night. The more I suffered the less I cared...

As a result of my sojourn in this establishment for the training of sportsmen I possessed at the age of fifteen a more extensive knowledge of "sexual manifestations" than many a "gentleman of the centre". It is possible that the masters did not know what was going on. Such a state of affairs could not and does not exist to-day. It is now the fashion to exclude "the hearties" from accusations of sexual interest or sadism, or masochism; but in my day it was they, the athletes, and above all the cricketers, who were allowed these traditional privileges. Boys were bullied, coerced and tortured for their diversion, and many a lad was started on strange things through no fault nor inclination of his own.

(4) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

During this period my father was abroad, chiefly in India, in Central Africa, or in Spain, reporting the Spanish-American war. My mother was then a very religious woman, and she was in perpetual indecision as to whether or not she should become a convert to Rome, a grave step at all times, but particularly for her, as she was the daughter of the Rector of St. Margaret's at Leicester. She was not the kind to hold her peace during spiritual conflict, and this no doubt accounts for my wide knowledge of the Bible and of the various dogmas. But religion has always left me untouched, my public-school training having killed the mystic that lurks within me, though my intimate friends always say I will yet become an intensely religious man!

(5) C.R.W Nevinson, letter to Dora Carrington (19th June, 1912)

I am now without a friend in the whole world except you.... I cannot give you up, you have put a reason into my life and I am through you slowly winning back my self-respect. I did feel so useless so futile before I devoted my life to you... I am aching for the companionship of Gertler, our talks on Art, on my work, his work and our life in general. God how fond of him I am. I never realised it so thoroughly till now....

If you still find it absolutely necessary to chuck me, remember should you ever need any help or companionship do please come back to me as I know I shall always like and respect you for the rest of my life. I most admire your self-control and grit to throw away a great deal of your happiness for your work even though I consider you are horribly wrong in doing so.

(6) Mark Gertler, letter to C.R.W Nevinson (December 1912)

I am writing here to tell you that our friendship must end from now, my sole reason being that I am in love with Carrington and I have reason to believe that you are so too. Therefore, much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends.

You must know that ever since you brought Carrington to my studio my love for her has been steadily increasing. You might also remember that many times, when you asked me down to dinner. I refused to come. Jealously was the cause of it. Whenever you told me that you had been kissing her, you could have knocked me down with a feather, so faint was I. Whenever you saw me depressed of late, when we were all out together, it wasn't boredom as I pretended but love.

(7) The Times (16th June, 1914)

Nevinson is a rebel in execution. He used to be a painter with a modest talent; but now he is like a singer with a small voice who has taken to shouting. Futurism, we are sure, is merely poison to him; and, if he has not lost his talent altogether, it will take him some time to recover it.

(8) Christopher Nevinson, The Daily Express (25th February 1915)

All artists should go to the front to strengthen their art by a worship of physical and moral courage and a fearless desire of adventure, risk and daring and free themselves from the canker of professors, archaeologists, cicerones, antiquaries and beauty worshippers...

Our Futurist technique is the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe.

(9) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

There were Claus and Wee, a retired major or two in white shirt-sleeves and cuffs, and Stanley Spencer with uncombed hair and a cockatoo, looking like a boy of thirteen. Mark Gertler was there, looking, with his curly hair, like a Jewish Botticelli. There were several very old gentlemen ; a completely civilized-looking Gilbert Solomon - now secretary of the R.B.A.; a long, thin fellow named Helps; Benson, already yellow with cigarette smoking; and I think Paul Nash and Ben Nicholson, very correct and formal. The atmosphere was as solemn as it was uncouth: self-consciousness ruled. In order to attract attention Fothergill developed a fit of temperament and tore up his drawing, then struck several matches which he threw in the air, and departed, I learned later, for his studio in Fitzroy Street. Presently he returned in changed clothes - a black coat, chef trousers and sandals, with a whippet at his heels - and prepared to make a fresh start upon the long road that leads to artistic achievement.

Then Tonks came in to criticize and stopped to have a long social talk with the retired majors first, discussing the vintages at some dinner-party they had attended the night before. He then came on to me and was not unpleasant. He asked me to define drawing, a thing I was fortunately able to do to his satisfaction, as I neither mentioned tone nor colour in my stammering definition but kept on using the word outline. But he nevertheless managed to shatter my self-confidence, and I was wringing wet by the time he left me to go on to Stanley Spencer....

Gradually I came to feel more at home at the new school, largely because of Wadsworth and Allinson. I formed a real friendship, too, with Gentler, who was the genius of the place and besides that the most serious, single-minded artist I have ever come across. His combination of high spirits, shrewd Jewish sense and brilliant conversation are unmatched anywhere. He is now famous enough to need little description, but in those days he had come on from the Polytechnic through the Jewish Education Society, and even as a young man he was an outstanding figure. His father had been an innkeeper in Austria and was then a furrier in Spitalfields. Through my early association with Toynbee Hall and the current Oxford movement, Whitechapel had no terrors for me; and being what Augustus John called a man cursed with an educational tendency, I was delighted to be able to help Gertler, I hope without patronage, to the wider culture that had been possible for me through my birth and environment. At any rate, I loved it, and his sense of humour prevented me from becoming a prig. Often, indeed, the pupil was able to teach the master a great deal, and it is impossible to convey the pleasures and enthusiasms we shared in the print room of the British Museum, in South Kensington, and in the National Gallery. We also shared the joys of eating, and I am proud and glad to say that both my parents were extremely fond of him. Never shall I forget his description of his visit to the Darwins at Cambridge, where he was painting a portrait. At dinner he was offered asparagus for the first time. Being accustomed to spring onions, he started at the white end first, and the beautifully mannered don followed suit in order not to embarrass him. He was a boxer, besides, au fait with every turn at the Shoreditch Empire, fond of the girls and adored by them.

By now Wadsworth, Allinson, Claus, Wee, Lightfoot, Curry, Spencer, and myself had become a gang, sometimes known in correct Kensington circles as the Slade coster gang because we mostly wore black jerseys, scarlet mufflers, and black caps or hats. Sometimes we were joined by the one-armed Badger Moody, who was the toughest of the lot. We were the terror of Soho and violent participants, for the mere love of a row, at such places as the anti-vivisectionist demonstrations at the " Little Brown Dog " at Battersea. We also fought with the medical students of other hospitals for the possession of Phineas, the bekilted dummy which stood outside a tobacconist's shop in Tottenham Court Road and was rightly or wrongly considered the mascot of the University College of London.

(10) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

As usual women found a way in the end; and before I left the Slade, affairs of the heart already existed between the gang and the girl students, ultimately breaking up the gang. I coquetted with a girl with whom Gertler was violently in love. Poor girl, she killed herself on the death of Lytton Strachey, years later. Brett, who eventually joined D. H. Lawrence, was another, while Ann somebody was pursued by both Allinson and Wadsworth, although she adored Wadsworth. They were grand girls, junior in years, but really much too old for us. In some things we were so very young and stupid, and we never hesitated to indulge in every form of dalliance which roused the jealousy of our best friends.

A model caused a good deal of trouble by producing a child which was put down not only to me but to seventeen other men, including Professor Tonks! Ian Strang always swore it was my child because he said it resembled me. I offered to marry the girl and got a very rude refusal.

(11) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

I had lost touch with most of the Slade students, but now and then I would see somebody and hear the news. Lightfoot had committed suicide because of unrequited love for a model. He had been one of the most talented men at the Slade and was an undoubted loss. I was shocked when I was told; and blase as I was, I felt bewildered when I witnessed the natural pride of the woman because a man had died for her. Gertler and Curry were good friends until Curry murdered a beautiful girl named Henry and tried to kill himself. For a while he lingered on, then in spite of all medical efforts to get him fit enough for the gallows he cheated them, poor fellow, and died. He was an Irishman from the Potteries, with a Napoleonic complex, and non-moral because of an over-reading of Nietzsche, a philosopher who profoundly influenced many of us.

(12) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

In the meanwhile P. Wyndham Lewis and I had become friendly, partly because he had asked me to join his party against Fry and the Omega workshop. To quote his letter, he felt Fry was "a shark in aesthetic waters and in any case only a survival of the greenery-yallery nineties".

I found Lewis the most brilliant theorist I had ever met. He was charming, and I shall always look back with gratitude to the enchanted time I spent with him. I little knew that he was to become my enemy. It is said that he suffers from thinking he is unpopular, but this is not so. He is essentially histrionic and enjoys playing a role ; while being misunderstood is one of his pleasures. A good talker, to be understood would mean, in his estimation, to be obvious. He likes to keep himself to himself. If only he would. However, I am anticipating. We were friendly then.

(13) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

It was dark when we arrived. There was a strong smell of gangrene, urine and French cigarettes, although a spark on the straw would have turned the place into a crematorium. Our doctors took charge, and in five minutes I was nurse, water-carrier, stretcher-bearer, driver, and interpreter. Gradually the shed was cleansed, disinfected and made habitable, and by working all night we managed to dress most of the patients' wounds.

The gratitude of the men was pathetic. They were certainly not so sure of the priests, who drifted about with a strange sense of being able to tell when a man was about to die. They would rush to him with the last sacrament and often be heartily cursed for their pains, for most of the soldiers disliked and distrusted them. As soon as a man died, the priests would try to collect all the walking wounded and then harangue their little audience, using the corpse as a sure sign that God was angry with France because she had disestablished the Church. When I came to talk with those priests I discovered most of them to be ignorant men, peasants by birth and Breton in origin. In their outlook they were pro-Vatican and anti-French, and that is saying the best of them, for some were actually pro-Germany because she was punishing France.

(14) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

The War was now settling down for the winter into some sort of trenches, and at our end of the line at any rate things began to sort themselves out. Gradually we received more help from the French authorities, and I must say they were grateful for what the Red Cross had done. A hospital had been started by the Red Cross and the Quakers at Malo-les-Bains, and I was given the job of driving the worst cases from the Shambles at Dunkirk to this point. Mostly we travelled by night ; but as the French and British armies had the same idea, the journey was often difficult.

From Dunkirk I was sent on to Woosten to work in a convent which had been converted into a field dressing-station. The nuns were working there as nurses, and they seemed to me to be literally without fear and prepared without a murmur to lay down their lives in the service of mankind. I should not like to think they had to share Heaven with those fat little priests I had met at Dunkirk. In the end the Army had to insist that they move to a place of greater safety, and they consented to go as far back as Poperinghe. We had another dressing-station at Ypres itself, which was shelled a good deal during the first battle of Ypres. On one occasion, as on others which have been recounted throughout the War, a tremendous attack was expected, and we were all turned out, Red Cross men as we were, to resist it, even to the cook with a long knife. Could we have claimed immunity because we were Red Cross men ? No, we should probably have rightly been shot as non-combatants and I should have been saved a lot of trouble.

It was at Woosten that I had a shell go clean through the back of my ambulance. To say I was impressed does not meet the case. I was amazed, and a trifle indignant. Certainly I was not as frightened as I ought to have been, for a shell is a shell, and if my van had not been a flimsy affair it would have exploded. Instead I had a nervous indigestion, but I slept like a log. Of this I am inordinately proud. I was nothing of a soldier, and considered my work as being something that applied to both sides. Looking back, I now know very well I was too vain to show much fear. It was only after a succession of events that men's nerves cracked, and I am thankful indeed that I escaped the strain unimpaired. Later, I became a driver from Dunkirk to Furnes and from Furnes to Ypres. When, at a still later period in the War, I saw that road during the Passchendaele battle, there was no sign of our convent at Woosten. It had been entirely demolished.

(15) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

My worst case was that of a dignified, bearded Frenchman of culture, who had twenty-seven wounds. He lingered between life and death for weeks, and I gave him nearly all my attention. Eventually he began to show signs of life under saline injections, and after a struggle the doctors saved him. He was a schoolmaster in Tunis, and years afterwards he wrote to me. His letters are treasures of mine, as the love of fellow men should be, and I felt humbled, embarrassed, and grateful. Of him and of those others I shall always cherish a memory. What citizens of the world they were ! I still possess some extraordinary mementoes of many of them, some of whom died - letters, trinkets, photographs. One devil-worshipper gave me his charms.

The whole atmosphere was unlike that of any English hospitals I was to see later. Religious discussion was of the frankest nature, especially after the visit of a foxy-faced cardinal who arrived with gifts for the wounded. Many of the men handed them back, saying he had got them out of old women by terrifying them with threats of hell. It was as well that the majority of the English staff did not understand much of the French conversation that went on, for it was impregnated with French realism, for all the idealism and camaraderie that peeped through because of the national trait which enables the French to be democratic without familiarity.

Dunkirk was one of the first towns to suffer aerial bombardment, and I was one of the first men to see a child who had been killed by it. There the small body lay before me, a symbol of all that was to come. Another time a Zeppelin loomed over us, guided by the treachery of a station-master, who lit a fire in the Dock. He was shot. It was said that a telephone wire had been laid before the War to Ostend. As I was working a great deal about the railway sheds which were being used as dressing-stations, I heard all kinds of stories about this man, but what impressed me most was the sense of outrage felt by the railwaymen when they realized they had for years been touching their caps to an ' espion '. At this time spy fever was sweeping Europe, and many a peasant was executed for lighting his pipe at the wrong moment ; but even if a Dunkirk chef-de gare were innocent - a thing I doubt-it was not the moment to start lighting a fire.

It was during this Zeppelin raid that I had a narrow shave. Fires broke out in the docks and were spreading to the Shambles. We had orders to evacuate all the helpless cases immediately. I dashed along with my ambulance. There were no lights anywhere and I had nothing but the fires to guide me, and as a result I had no sooner filled the ambulance and started than I jammed a wheel in the railway points that ran beside the shed. About a dozen men came to my rescue, and we pulled and lifted and hammered and levered. Nobody noticed an enormous engine of a troop train slide out of the darkness towards us, but by a miracle the driver spotted us in time and pulled up three feet from the bonnet. Another few seconds would have seen the end of all of us, to say nothing of the wounded, who were shrieking piteously every time we banged at the wheels of the ambulance. With French adaptability the engine-driver climbed down, tied an old rope to the ambulance, and backed the entire troop train to get us out, with nothing worse than my front wheels out of alignment. Congratulations on all sides became so voluble that it was difficult to hear what was being said and impossible to believe that the Battle of the Dunes was at its height only a few miles off.

(16) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

After a time we got a rush of wounded, and because I was an artist the sergeant-major put me in charge of the "balmy ones" in the observation ward and the detention cases. This is the worst job I have ever tackled in my life. Lots of the balmy ones were indeed balmy and needed every attention, while the detention cases were made up of malingerers and ne'er-do-wells whose patriotism had outrun their caution and who now wished to be quit of the Army by pretending to have every disease under the sun. I had a good deal of power with the mental cases, who themselves were a mixed lot. Some were mad, some were shell-shocked, and some were nit-wits. The change of environment and breaking of routine, or a dreadful experience in "the line", or for some the proximity day and night of other men in the same plight, sent them completely into a world of hallucination and persecution, especially the latter. There would be strange grievances against the man in the next bed, or the sergeant-major, or the nurses, and particularly against their wives. I began to have an uneasy feeling that I was catching their complaint, and had it not been for the observation of one of the doctors I believe I should have become one of the balmy ones myself. Scientific or not, I am convinced that mental instability is infectious. I was moved into the blind-and-deaf ward, the deaf being terribly morose and the blind extremely gay. For some months this went on; then we were informed that we were to be part of a draft for Mesopotamia.

In the meanwhile I had formed a great friendship with Ward Muir, a writer, journalist, and photographer. He suffered from T.B. and he was continually volunteering for dangerous service and being turned down. His lungs had collapsed, his heart had moved from his left side to his right, yet he was a man of indomitable courage. He became the editor of the hospital magazine and in this my war drawings were reproduced.

The London Group was still in existence, and my people arranged for me to exhibit La Patrie, The Road to Ypres, and The First Bombardment of Ypres, three pictures which created a tremendous stir at the time. The intellectuals made violent attacks on them, and I remember Harold Monro saying, "What on earth are you doing journalistic clippings for?" Of course, the Clive Bell Group dismissed them as being "merely melodramatic". The Times was horrified and said the pictures were not a bit like cricket, an interesting comment on England in 1915, when war was still considered a sport which received the support of the clerics because it brought out the finest forms of self-sacrifice, Christian virtues, and all the other nonsense. I had painted what I had seen, without a thought for exhibition. To me the soldier was going to be dominated by the machine. Nobody thinks otherwise today, but because I was the first man to express this feeling on canvas I was treated as though I had committed a crime. The public, however, as usual, showed more intelligence than the intelligentsia, and I was also well treated by the general press.

(17) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

When I saw the orderly officer I felt like death, so he put me on light duty. This meant that I had to spend the next few hours in carrying sacks of coal from the lorries to the furnaces, and of course I had to try. Doctors had no idea what light duty meant: the sergeants saw to that. I collapsed, was taken to the Receiving Ward and ordered to take a cold bath. Eventually, by the grace of God, I was examined by the famous Dr. Humphreys. He took one look at me, checked my temperature, and ordered me to be put to bed immediately. This I was just able to do myself. My temperature went up and up, and for weeks I was on the danger list with acute rheumatic fever.

(18) P. G. Konody, The Sunday Observer (14th March, 1915)

Mr. Nevinson's steadfastness of purpose must surely remove any doubt as to his sincerity. Hem believer in the theories of Futurism as expounded by Boccioni and his Italian followers: the displacement and interpretation of objects, the search for "force lines" dynamism, and the cutting of the very atmosphere into geometric planes - a meeting point of Cubism and Futurism....

He has realised the uselessness of painting pictures that have no meaning for anybody but the artist himself, and therefore places his Futurist experiment on a lucid basis of realism. His Returning to the Trenches is really an uncommonly interesting picture, in which he has found an extremely expressive formula for the rhythmic marching of a body of French infantrymen fully armed and laden with all the paraphernalia for a prolonged stay in the trenches.

(19) Charles Lewis-Hind, The Evening News (16th March, 1916)

You peer into a pit in the zone of fire; barbed wire stretches across the surface of the machinomorphic pit; above is the grey, clear sky of France. In the pit are four French soldiers. One lies dead. The three living men are conscious of one thing only - the control of their death-scattering mitrailleuse. There it lurks, rigid and venemous, ready to spit out immense destruction. And the gunners? Are they men? No! They have become machines. They are as rigid and as implacable as their terrible gun.

(20) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

On our return to London I still had two days' leave, and I painted La Mitrailleuse and The Deserted Trench on the Yser. It was a queer honeymoon and typical of my wife that she put up with it. Again I was feeling ill and when I returned to the hospital I reported sick.

When I saw the orderly officer I felt like death, so he put me on light duty. This meant that I had to spend the next few hours in carrying sacks of coal from the lorries to the furnaces, and of course I had to try. Doctors had no idea what light duty meant: the sergeants saw to that. I collapsed, was taken to the Receiving Ward and ordered to take a cold bath. Eventually, by the grace of God, I was examined by the famous Dr. Humphreys. He took one look at me, checked my temperature, and ordered me to be put to bed immediately. This I was just able to do myself. My temperature went up and up, and for weeks I was on the danger list with acute rheumatic fever.

After a time I began to recover, but my hands were in an appalling state, scarcely human, and my wife and my Mother were terribly worried. My Mother saw Sir Bruce Porter about me, and through his kind offices I was examined by a medical board, whose president, Sir Alfred Gould, recommended my total discharge. The thought that I was to "get my ticket" went to my head. I was the envy of the ward.

(21) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

Yet when I found a measure of success, the Bloomsburies accused me of every form of pushfulness and publicity. I suppose it was extremely artful of me to lie in my Mother's home and wonder if I ever should be free from pain again, but I have always failed to see why such conduct should be termed pushful. There are still those, of course, who think the Great War was a "stunt" of mine!

My success I owe to Frank Rutter, Lewis Hind, P. G. Konody, and the Allied Artists. Art critics were not only powerful in those days, but constructive and helpful. I was unable to do anything for myself, and Lewis Hind, who himself was recovering from a grave illness, asked for some reproductions of my work. He took these without my knowledge to Brown and Phillips, of the Leicester Galleries, and I was astounded and delighted when I was offered a one-man show on a date which had been reserved by Munnings and cancelled by him. As usual, the Galleries did not hold out much hope of success. Brown was quite charming and assured me they would do their best, but he warned me I must not expect to benefit financially.

My blood had begun to course in normal fashion, my joints were loosening and my hands were gradually beginning to look human. I was fired with the opportunity which had come my way, and I painted and painted and painted. Those pictures which had been sold I borrowed, and we did everything to help the show. Every one we knew was asked to the private view, but the times were abnormal, many of our friends fell by the wayside, and it was sparsely attended. The Press had little to say about it and things were beginning to look black when, somehow or other, the clientele of the Leicester Galleries began to come along. I had a letter from Professor Sir Michael Sadler to say he would be at the Galleries at eleven o'clock one Tuesday morning. Knowing his punctilious habits, I was there to the minute, and so was he. He bought my Marching Men and three other war pictures. This was grand. Then Arnold Bennett bought La Patrie , and slowly but surely the exhibition sold right out. According to the advertisements of Brown and Phillips, I became the talk of London.

(22) General Ian Hamilton, on the paintings of Christopher Nevinson (1918)

The appeal made to a soldier by these works lies in their quality of truth. They bring him closer to the heart of his experiences than his own eyes could have carried him.

In France, that flesh and blood column marching into the grey dawn seemed simply-a column of march. Seen on this canvas it becomes the symbol of a world tragedy - a glimpse given to us of Destiny crossing the bloodiest page in History.

Look at that star shell! To the soldier crouching in a mine crater, or crawling from cover to cover to cut barbed wire, the sudden ball of fire that fills his dark hiding-place with ghostly light is a murderous eye betraying him to enemies in ambush. Here, truer to the truth, it takes on a mystic semblance of the Holy Grail, poised over the trenches, bearing its mystic message to the souls of our happy warriors.

Then those aeroplanes ! We take some linen and wood and make what, when all is said and done, seems a very poor imitation of an insect. Into its body we thrust a small steel hear ; feed it with a drop of petrol ; turn a handle, and lo ! rapturously, it scales the rainbow skies and rides the stars. And yet we know it is a machine-a poor imitation of a grasshopper trying to look at a distance like a gilded butterfly. But war spiritualizes, magnifies, intensifies. The artist lets us glance a moment through his magic lens; we see what he sees.

(23) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

Owing to the interest shown, the exhibition was extended for a further week, and when it was closed I received a flood of publicity. The newspapers had heard about my success, a little late perhaps, and they proceeded to make up for lost time. I became "news" in Fleet Street. Clutton Brock's leading article in The Times Literary Supplement a few days before the exhibition closed was of enormous help to me, although the general trend of the article was entirely antagonistic. My obvious belief was that war was now dominated by machines and that men were mere cogs in the mechanism. Brock voiced the opinion of a great many people, particularly of the old Army type, that the human element, bravery, the Union Jack, and justice, were all that mattered.

Nowadays, of course, everybody takes the mechanized Army for granted, but in those early days I got into hot water simply because I was the first to paint it. I, who had seen more of human anguish than the majority of artists, was accused of being dehumanized. It was said I believed man no longer counted. They were wrong. Man did count. Man will always count. But the man in the tank will, in war, count for more than the man outside. It was the essential difference between the civilian and the soldier, and not unnaturally the public agreed with the civilian. What was a joy to me was that my work was taken seriously and my point of view debated.

All manner of people had attended the exhibition. Bernard Shaw and Galsworthy were there. Conrad came, and told me incidentally that I had written some of the finest prose he had read in the younger generation: Heaven knows why, for he vowed he was not confusing me with my father. William Archer cried: an exquisite compliment. Officers of high rank came, and terrified me so much that I nearly stood at attention. Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Balfour, Mrs. Asquith, Winston Churchill, Lady Diana Manners, and Garvin were to be seen arguing before my pictures. It happened that I was the first artist to paint war pictures without pageantry, without glory, and without the over-coloured heroic that had made up the tradition of all war paintings up to this time. I had done this unconsciously. No man saw pageantry in the trenches. My attempt at creating beauty was merely by the statement of reality, emotionally expressed, as one who had seen something of warfare and was caught up in a force over which he had no control.

Indignation amongst the older men was therefore intense, and the clerical opposition was voluble. It is strange to say it to-day, but I am proud to think that three canons actually preached against me and my pictures. Now, of course, the entire English-speaking world, including America, and most people in France and Russia, would never dream of saying my outlook was wrong. It is, indeed, opposed only by the extremists of Italy, the paranoiacs of Germany, and the Fascists of Spain. In the whole world, Japan is the only nation which still whole-heartedly regards war as man's finest achievement.

(24) C.R.W Nevinson, Exhibition Catalogue (1918)

This collection of pictures represents the work of the last seven months. Most of them were completed at home after my return from the Western Front where in my capacity as one of the Official Artists I was attached to various divisions and given every facility for sketching and recording the ordinary every,day life and work of the Imperial Forces.

This exhibition differs entirely from my last in which I dealt largely with the horrors of war as a motive. I have now attempted to synthesize all the human activity and to record the prodigious organization of our Army, which was all the more overwhelming to me when I contrasted it with what I remembered on the Belgian front 1914-15.

All of my work had to be done from rapid shorthand sketches made often under trying conditions in the front line, behind the lines, above the lines in observation balloons, over the lines in aeroplanes and beyond them even to the country at present held by the enemy.

I relied chiefly on memory, a method I learnt as a student in Paris and for which I am ever grateful: nature is far too confusing and anarchic to be merely copied on the spot. Although the followers of the "plein air" school always laid great stress on working directly from nature, their work is none the less pure invention marred by all manner of nature's accessories. An artist's business is to create, not to copy or abstract, and to my mind creation can only be achieved when, after a close and continuous observation and study of nature, this visual knowledge of realities is used emotionally and mentally.

Every form of art must be and has always been a creation worked out within definite unrealistic conventions or formulas which should never be judged by what they represent. It may even be that they represent nothing at all. Most of the finest works of art of the world express some visual realities, but many absolutely none.

(25) C.R.W Nevinson, quoted in The Leader (13th November, 1920)

Today New York is, for the artist, the most fascinating city in the world. She is like a young woman, splendid in her unconscious strength and beauty, cold and hard perhaps, but only as youth always is. She doesn't soothe the nerves; she stimulates action.

(26) C.R.W Nevinson, Paint and Prejudice (1937)

Another sitter of mine was Sinclair Lewis, the strangest literary man I have known. He was restless, clownish, and intense as only Americans can be, and he prowled round my studio incapable of sitting still, while all the time he poured out the most remarkable monologue of love and hate, shrewdness and sentimentality, that it can have been the lot of any portrait painter to hear. He used to leave me with a sense of exhaustion and elation that I have never known any other human capable of producing.

He was obsessed by a dread of the future and of his own in particular, fearing that his creative faculties would dry up ; and all this before he wrote, Babbitt, The Man Who knew Coolidge, and It Can't Happen Here. His irony was devastating, and I wish I dared write some of the thrusts he made at contemporary writers, French, English and American, but I have been warned that it is possible in this country to write the truth only of the dead. All the time I am struggling with the awful fear that anything I have said will be held in evidence against me.

I have sometimes wondered if Sinclair Lewis looks back on that particular visit to England with dissatisfaction. Never have I met a man so sensitive and yet with such a gift of putting his foot in it. He would break all the snob rules laid down by the mumbo jumbos of English literature, and infuriate everyone with a taint of preciosity. Sometimes it would seem that a devil possessed him, although I recall two occasions when he was worsted.

Once we were at dinner with Somerset Maugham, and among those present were Mrs. Maugham, Knoblock, McEvoy, Osbert Sitwell, and Eddie Marsh. There was nobody in the party to whom Sinclair Lewis could take exception; and as for our host, I have always noticed like many others that he is the one man admired by all authors. After dinner, Sinclair Lewis took Eddie Marsh's monocle, stuck it in his own eye, and began parading up and down with Eddie Marsh following like a dog on a string. Then, to amuse himself, he parodied high-brow conversation in the best Oxford manner, at times imitating McEvoy's cracked voice, which was sometimes bass and sometimes treble. All of us were embarrassed, as the parody was grotesquely realistic, and I saw McEvoy pull his hair over his forehead and begin to look like a village idiot, a danger signal in him.

I knew it would come, and sure enough McEvoy suddenly interrupted the parody and inquired if Sinclair Lewis was an American. Sinclair Lewis looked taken aback at the question, but fell right into trouble.

"Yes," he said. "That is what makes me so sick with you condescending Englishmen."

"I don't care if you are sick," replied McEvoy calmly. "In fact I should be rather pleased. But you are just the man to tell me why old Americans are so much nicer than young ones."

Poor Lewis. The eye-glass fell from his eye and he was silent until we left.