Mark Gertler

Mark Gertler, the youngest of the five children of Louis Gertler, master furrier, and his wife, Kate (Golda) Berenbaum, was born at 16 Gun Street, Spitalfields on 9th December, 1891. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Przemyśl in Galicia.

According to his biographer, Sarah MacDougall: "Gertler spent his formative years in the poverty and unity of the Jewish community, attending schools in Settles Street and Deal Street (1897–1906). He showed precocious artistic talent (making his first drawing at the age of three) and, inspired by pavement artists, advertising posters, and the autobiography of the painter William Powell Frith, resolved to become a professional artist."

In 1906 Gertler became an art student at Regent Street Polytechnic, but a year later was forced through poverty to begin an apprenticeship at Clayton and Bell, glass painters. However, he continued to attend art classes in the evenings. In his early years he painted his own family repeatedly.

In 1908 Gerter met the artist, William Rothenstein. After seeing the work of the sixteen-year-old East Ender he wrote to his father: "It is never easy to prophesy regarding the future of an artist but I do sincerely believe that your son has gifts of a high order, and that if he will cultivate them with love and care, that you will one day have reason to be proud of him. I believe that a good artist is a very noble man, and it is worth while giving up many things which men consider very important, for others which we think still more so. From the little I could see of the character of your son, I have faith in him and I hope and believe he will make the best possible use of the opportunities I gather you are going to be generous enough to give him." Rothenstein managed to secure a place at the Slade School of Fine Art and arranged for his fees to be paid by the Jewish Educational Aid Society.

Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989), has argued: "At the Slade, Mark was at first something of a misfit. He had started school late in life, and had left it at the age of fourteen. His hair was short and his clothes were different. Most of all, however, the other students found him too serious and too intense. He was extremely handsome, with huge dark eyes, pale skin, and a thin body, and he was both solemn and passionate about his art. Only at the polytechnic had he finally been introduced to museums and systematic schooling in the history of art, including the old masters. When he first arrived at the Slade at seventeen, he had the fervour of a convert who has surmounted great obstacles for his religion. In contrast, his fellow students seemed privileged and rather frivolous. Yet his early opinions of them were not untouched by envy."

Eventually he made friends with a group of very talented students. This included C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, John S. Currie, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee. This group became known as the Coster Gang. According to David Boyd Haycock this was "because they mostly wore black jerseys, scarlet mufflers and black caps or hats like the costermongers who sold fruit and vegetables from carts in the street".

Nevinson commented that the Slade "was full with a crowd of men such as I have never seen before or since." He also wrote that Gertler was "the genius of the place... and the most serious, single-minded artist I have ever come across." Gertler was considered the best draughtsman to study at the Slade since Augustus John. Another student, Paul Nash, said that Gertler riding high "upon the crest of the wave".

In 1910 Dora Carrington joined the Slade School. Gertler and C.R.W. Nevinson both became closely attached to Carrington. According to Michael J. K. Walsh, the author of C. R. W. Nevinson: The Cult of Violence (2002): "What he (Nevinson) was not aware of was that Carrington was also conversing, writing and meeting with Gertler in a similar fashion, and the latter was beginning to want to rid himself of competition for her affections. For Gertler the friendship would be complicated by sexual frustration while Carrington had no particular desire to become romantically involved with either man."

Mark Gertler became a close friend of C.R.W. Nevinson. Gertler wrote to William Rothenstein: "My chief friend and pal is young Nevinson, a very, very nice chap. I am awfully fond of him. I am so happy when I am out with him. He invites me down to dinners and then we go on Hampstead Heath talking of the future." According to Michael J. K. Walsh: "Together they studied at the British Museum, met in the Café Royal, dined at the Nevinson household, went on short holidays and discussed art at length. Independently of each other too, they wrote of the value of their friendship and of the mutual respect they held for each other as artists."

C.R.W. Nevinson recorded in his autobiography, Paint and Prejudice (1937): "I am proud and glad to say that both my parents were extremely fond of him." Henry Nevinson recalled: "Gertler came to supper, very successful, with admirable naive stories of his behaviour in rich houses and at a dinner given him by a portrait club, how he asked to begin because he was hungry."

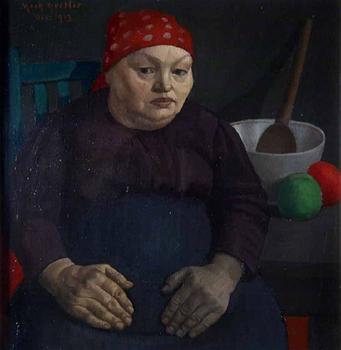

Mark Gertler continued to paint portraits of family members. His mother became the focus of these portraits. In 1911 he wrote: "I am painting a portrait of my mother. She sits bent on a chair, deep in thought. Her large hands are lying heavily and wearily in her lap. The whole suggests suffering and a life that has known hardship. It is barbaric and symbolic. Where is the prettiness! Where! Where!" The completed painting was called Portrait of the Artist's Mother.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska introduced Edward Marsh to Mark Gertler and John S. Currie. Marsh was a homosexual and as David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Marsh's keenness for painting was matched only by his passions for poetry and handsome young men." He became very attached to Gertler who he took to the theatre. He told Rupert Brooke: "Gertler is by birth an absolute little East End Jew. Directly I can get about I am going to see him in Bishopsgate and be initiated into the Ghetto. He is rather beautiful, and has a funny little shine black fringe."

John S. Currie was invited by Marsh to dinner at Gray's Inn. He brought Dolly Henry with him and Marsh described her as "an extremely pretty Irish girl with red hair". The following day Marsh wrote to Rupert Brooke: "Currie came yesterday I have conceived a passion for both him and Gertler, they are decidedly two of the most interesting of les jeunes, and I can hardly wait till you come back to make their acquaintance."

Mark Gertler and John S. Currie now became Marsh's artistic mentors. They argued that he should buy the work of their friend, Stanley Spencer. Marsh told Brooke: "They both admire Spencer more than anyone else. Gertler was to have taken me to see him (at Cookham) tomorrow, but it's had to be put off... I shall be buying some pictures soon! I think I told you I was inheriting £200 from a mad aunt aged 90, it turns out to be nearer four hundred than two! So I'm going to have my rooms done up and go a bust in Gertler, Currie and Spencer."

Edward Marsh met Spencer and eventually purchased the Apple Gatherers for 50 guineas. Marsh told Brooke that he had hung the painting in his spare bedroom. "I can't bring myself really to acquiesce in the false proportions, though in every other respect I think it magnificent." He added that Spencer "has a charming face" and that "we got on like houses on fire." However, Marsh complained about his lack of output: "Spencer... only had about two things to show, he does work slowly." Brooke responded: "I hate you lavishing all your mad aunt's money on those bloody artists."

Marsh introduced Gertler to Ottoline Morrell and Gilbert Cannan. Morrell invited Gertler to tea at her home at Bedford Square. She asked him "if he didn't find it hard reconciling his home life with the life he lived at the Slade, and with Mr Eddie Marsh". He admitted "that he could not but feel antagonistic to the smart and the worldly, while at the same time he felt depressed by the want of cultivation of his own people."

Gertler became very friendly with Dorothy Brett. In May 1912 she invited him to a social function in Mayfair. He borrowed an evening dress suit from a friend, but the trousers were too short. He told her: "No one need know. The upper part of me will be perfect! I shall be able to look Aristocracy straight in the face."

On 12th June 1912, Dora Carrington wrote to C.R.W. Nevinson. The letter has not survived, but his response to it has. It starts: "Your note came as a horrible surprise to me. I cannot guess what has happened to make you wish to do without me as a friend next term." It seems that Carrington had complained about the intimacy of his letters. He added: "I swear I will never speak a word to you as your lover... I promise you I will be a great friend of yours nothing more and nothing less and if you want to get simple again I am only too willing to do the same."

Carrington also received a letter from Gertler asking her to marry him. When she rejected this proposal he wrote a further letter on 2nd July, suggesting: "Your affections are completely given to Nevinson. I must have been a fool to stand it as long as I have, without seeing through you. I have written to Nevinson telling him that we, he and I, are no longer friends." In the letter he argued, "much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends." Gertler replaced Nevinson with John S. Currie as his main friend.

In July 1912, Mark Gertler, John S. Currie and Dora Henry went on holiday to Ostend. They had a good time but Gertler showed concern about Currie's behavior. He suggested that Currie's love of the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche had left him immoral. Stanley Spencer strongly disliked Currie and said: "I cannot bear him." Adrian Allinson pointed out that Currie was insanely jealous of Dolly: "Violent jealously continually drove Currie to threats of murder... Dolly's beauty, and pity for her lot, aroused in more than one painter the desire to replace the Irishman, so that Currie's jealousy, originally groundless, in time created the conditions for its own justification."

C.R.W. Nevinson continued to plead with Dora Carrington to remain his friend: "I am now without a friend in the whole world except you.... I cannot give you up, you have put a reason into my life and I am through you slowly winning back my self-respect. I did feel so useless so futile before I devoted my life to you." He also wanted a return of Gertler's friendship: "I am aching for the companionship of Gertler, our talks on Art, on my work, his work and our life in general. God how fond of him I am. I never realised it so thoroughly till now."

Gertler now wrote to Nevinson: "I am writing here to tell you that our friendship must end from now, my sole reason being that I am in love with Carrington and I have reason to believe that you are so too. Therefore, much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends. You must know that ever since you brought Carrington to my studio my love for her has been steadily increasing. You might also remember that many times, when you asked me down to dinner. I refused to come. Jealously was the cause of it. Whenever you told me that you had been kissing her, you could have knocked me down with a feather, so faint was I. Whenever you saw me depressed of late, when we were all out together, it wasn't boredom as I pretended but love."

However, Dora Carrington refused to begin a sexual relationship with Gerter during this period. Vanessa Curtis has argued: " Although passionate towards Gertler when discussing art, Carrington, at eighteen, had not yet had her sexuality awakened; her upbringing had taught her to repress her innermost feelings. She was looking for a platonic soul mate, but what she found was a man who was highly sexed and constantly irritated and frustrated by Carrington's lack of passion. The heartbreaking letters that passed regularly between them pay sad testimony to the anguish that this long relationship caused."

St John Hutchinson described Gertler while at Slade School as "a Jew from the East End with amazing gifts of draughtsmanship, amazing vitality, … a sense of humour, and of mimicry unique to himself - a shock of hair, and the vivid eyes of genius and consumption". Several important collectors became aware of his work and those who purchased his early paintings include Edward Marsh, private secretary to Winston Churchill. Marsh was so impressed with Gertler's work that he paid him £10 a month in return for first refusal on his paintings. Morrell introduced him to Walter Sickert and other important figures in the art world.

Gertler seemed uncomfortable in this world. In December 1912 he wrote to Dora Carrington: "Yes, my isolation is extraordinary. I am alone, alone in the whole of this world! Yes, if only like my brothers I was an ordinary workman as I should have been. But no! I must desire, desire. How I pay for those desires! Oh! God! Do I deserve to be so tormented? By my own ambitions I am cut off from my own family and class and by them I have been raised to be equal to a class I hate! They do not understand me nor I them. So I am an outcast. As I look at my desk I laugh, for there are dozens of notices of me in the daily papers, a lot of them praising my talents. Oh! yes I am quite well known, and yet alone."

In December 1913 Gertler, C.R.W. Nevinson and John S. Currie exhibited at the Chenil Gallery. The art critic of The Sunday Observer commented that "when their modernity is closely investigated it seems to belong more to the fifteenth century than to the twentieth century." Eventually all three men abandoned this style. Nevinson described it as too "early Italian and custumy" and argued that "we must guard against raking up the past."

Gertler found Currie's behaviour increasing erratic and he told Dorothy Brett: "Friendships are terribly difficult to manage and I don't think they are worth the trouble. Dolly Henry is not intelligent at all - that's the trouble. Frankly I prefer to stand alone. I need no great friend at all. Ties are a terrible nuisance and hindrance to an artist. I know him far too well for that... he has friends and a woman whom he loves. Remember that I am absolutely alone and I have loved without the slightest success. If anyone will suffer it ought to be me. Perhaps no one of my age has suffered as much as I."

Mark Gertler continued to develop his own style. He told Dora Carrington: "Newness doesn't concern me. I just want to express myself and be personal... I don't want to be abstract and cater for a few hyper-intellectual maniacs. An over-intellectual man is as dangerous as an over-sexed man. The artists of today have thought so much about newness and revolution that they have forgotten art.... Besides I was born from a working man. I haven't had a grand education and I don't understand all this abstract intellectual nonsense."

Mark Gertler moved in with Edward Marsh in 1914. Gertler refused to support Britain's involvement in the First World War. "I can never set out to please - my greatest spiritual pleasure in life is to paint just as I feel impelled to do at the time... But to set out to please would ruin my process." The two men argued about the conflict and on 19th October, 1915, Gertler decided to leave Marsh: "I have come to the conclusion that we two are too fundamentally different to continue friends. Since the war, you have gone in one direction and I in another. All the time I have been stifling my feelings. Firstly because of your kindness to me and secondly I did not want to hurt you. I am I believe what you call a Passivist. I don't know exactly what that means, but I just hate this war and should really loathe to help in it."

Gertler became friendly with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell. In 1915 the Morrells purchased Garsington Manor near Oxford and it became a meeting place for left-wing intellectuals. This included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy, Dorothy Brett, Siegfried Sassoon, D.H. Lawrence, Frieda Lawrence, Ethel Smyth, Katherine Mansfield, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Herbert Asquith, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

Mark Gertler became romantically involved with Katherine Mansfield. He claimed that at one of the parties at Garsington Manor he "made violent love to Katherine Mansfield! She returned it, also being drunk. I ended the evening by weeping bitterly at having kissed another man's woman and everyone was trying to console me. Mansfield told Frieda Lawrence that she was in love with Gertler. Frieda accused Mansfield of leading the younger man on, and threatened never to speak to her again.

In February 1915 Gertler became friendly with Lytton Strachey. He wrote to Dora Carrington: "I have become great friends with Lytton Strachey. He spends a large part of his time in his cottage, which is in a place near Marlborough - all alone. We carry on a correspondence. He is a very intellectual man - I mean in the right sense. I should think he ought to do good work."

Dora Carrington continued to see Gertler, but refused to have a sexual relationship with him. On 16th April 1915 she wrote to Gertler: "I cannot love you as you want me to. You must know one could not do, what you ask, sexual intercourse, unless one does love a man's body. I have never felt any desire for that in my life: I wrote only four months ago and told you all this, you said you never wanted me to take any notice of you when you wrote again; if it was not that you just asked me to speak frankly and plainly I should not be writing. I do love you, but not in the way you want.... Can I help it? I wish to God I could. Do not think I rejoice in being sexless, and am happy over this. It gives me pain also."

In February 1915 Gertler became friendly with Lytton Strachey. He wrote to Dora Carrington: "I have become great friends with Lytton Strachey. He spends a large part of his time in his cottage, which is in a place near Marlborough - all alone. We carry on a correspondence. He is a very intellectual man - I mean in the right sense. I should think he ought to do good work."

Carrington became very angry when Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell began to interfere with her relationship with Gertler. She told Lytton Strachey on 28th July 1916: "I spent a wretched time here since I wrote this letter to you. I was dismal enough about Mark and then suddenly without any warning Philip Morrell after dinner asked me to walk round the pond with him and started without any preface, to say, how disappointed he had been to hear I was a virgin! How wrong I was in my attitude to Mark and then proceeded to give me a lecture for a quarter of an hour! Winding up by a gloomy story of his brother who committed suicide. Ottoline then seized me on my return to the house and talked for one hour and a half in the asparagus bed, on the subject, far into the dark night. Only she was human and did see something of what I meant."

In 1916 Gilbert Cannan published the novel Mendel: A Story of Youth. It was based on the lives of his friends, Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington and John S. Currie. The novel tells the story of an impetuous but talented immigrant painter, Mendel Kuhler (Gertler) who is in love with Greta Morrison (Carrington), who refuses to sleep with him. D. H. Lawrence explained how "Gertler... has told every detail of his life to Gilbert... who has a lawyer's memory and he has put it all down, and so ridiculously when it comes to the love affair... it is a bad book - statement without creation - really journalism." Carrington was furious that Gertler had told Cannan about their relationship: "How angry I am over Gilbert's book. Everywhere this confounded gossip, and servant-like curiously. It's ugly and so damned vulgar."

Soon after the publication of this book, Carrington agreed to sleep with Gertler. According to Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989): "At long last they embarked upon a sexual relationship, with a predictable result. Carrington failed to get really interested and it proved a tremendous disappointment after the years of difficulty that preceded it.... She and Mark continued to sleep together, unsatisfactorily, for some time."

Gertler continued to complain about her need to have relationships with several different people. In December 1916 he wrote to Dora Carrington complaining about these "advanced" views: "For God's sake don't torture me by not letting me see much of you - I must see you very often. I shan't worry you for much sugar if only I can see you and talk - I must, I must. And if any other man touches any part of your beautiful body I shall kill myself - don't forget that! I could not bear such a thing. Give me time - give me at any rate a year or so of happiness. I deserve it - you have tortured me enough in the past. Perhaps later I shall be able to be advanced and reasonable about your other friends. Then you can have other ships... Don't believe those advanced fools who tell you that love is free. It is not - it is a bondage, a beautiful bondage. We are bound to one another - you must love the bondage. How I hate your advanced philosopher self! Yes I hate that part of you - you have lately added hateful parts to yourself. If you really loved me you could not be so advanced. A person really in love is not advanced. I loathe your many ships idea... Also you would not call love-making vulgar if you were in love. You would not arrange for it only to happen three times a month."

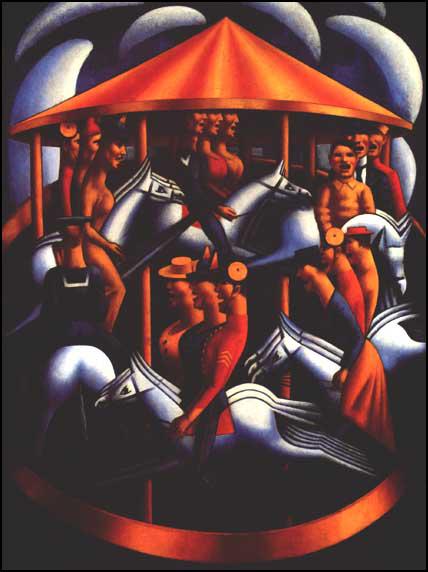

After the Battle of the Somme Gertler began work on Merry-Go-round (1916). He wrote that "I live in a constant state of over-excitement, so much do my work and conception thrill me. It is almost too much for me and I am always feeling rather ill. Sometimes after a day's work I can hardly walk." His friend, Lytton Strachey, commented: "I felt that if I were to look at it for any length of time. I should be carried away, suffering from shellshock. I admired it, of course; but as for liking it - one might as well think of liking a machine-gun."

Considered by many art critics as the most important British painting of the war, Merry-Go-round, shows a group of military and civilian figures caught on the vicious circle of the roundabout. One gallery refused to show the painting because Gertler was a conscientious objector. Eventually it appeared in the Mansard Gallery in May, 1917. D. H. Lawrence wrote to Gertler: "I have just seen your terrible and dreadful picture Merry-go-round. This is the first picture you have painted: it is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great and true. But it is horrible and terrifying. If they tell you it is obscene, they will say truly. You have made a real and ultimate revelation. I think this picture is your arrival."

In 1918 he wrote to Dorothy Brett: "It is not the fear of starving or anything as simple as that, that haunts me. It is the general principle. I long to be free and independent for my living, both from people and my work. To have to think of selling pictures, all the time and to tolerate silly people coming up here to see them, is awful. It creeps into all one's moods and spoils everything."

Gertler got to know Virginia Woolf during this period. She wrote in her diary: "His face is a little tight and pinched; but the word he would wish one to use of him is powerful. His mind certainly has a powerful spring to it. He is also evidently an immense egoist. He means by sheer willpower to conquer art. But bating this sort of aggression he was well worth talking to. Leonard noticed his amazing quickness. He would soon have told us the story of his life. I felt about him, as about some women, that unnatural repressions have forced him into unnatural assertions."

The first symptoms of tuberculosis appeared in April 1920. While in Banchory Sanatorium near Aberdeen, he painted Trees at Sanatorium. Although in poor health, Gertler continued to have yearly exhibitions at the Goupil Gallery. Gertler's post-war work was profoundly influenced by post-impressionism. The early 1920s were Gertler's most successful period commercially.

In 1925 he was admitted to Mundesley Sanatorium in Norfolk. He was forced to return in 1929 and became depressed by the loss of two close friends, Katherine Mansfield and D.H. Lawrence, from the disease.

Gertler married Marjorie Greatorex Hodgkinson, a former Slade School student, on 3rd April 1930. He received a wedding gift from Dora Carrington. He replied that he had recently re-read her letters: "It certainly made most moving reading. It must have been a most extraordinary and painful time for both of us. But we were both very young and probably unsuited. And it is over now and nobody's fault." Two years later Marjorie gave birth to a son, Luke.

Gertler had difficulty selling his work in the 1930s and although he had a few loyal supporters such as J. B. Priestley and Aldous Huxley, he was forced to teach part-time at Westminster Technical College. His old patron, Edward Marsh, had forgiven Gertler for his pacifism, continued to buy his paintings even though he admitted he no longer liked or understood his work.

Dora Carrington committed suicide on 11th March 1932. Frances Marshall was with Ralph Partridge, her husband, when he received a phone-call on 11th March 1932. "The telephone rang, waking us. It was Tom Francis, the gardener who came daily from Ham; he was suffering terribly from shock, but had the presence of mind to tell us exactly what had happened: Carrington had shot herself but was still alive. Ralph rang up the Hungerford doctor asking him to go out to Ham Spray immediately; then, stopping only to collect a trained nurse, and taking Bunny with us for support, we drove at breakneck speed down the Great West Road.... We found her propped on rugs on her bedroom floor; the doctor had not dared to move her, but she had touched him greatly by asking him to fortify himself with a glass of sherry. Very characteristically, she first told Ralph she longed to die, and then (seeing his agony of mind) that she would do her best to get well. She died that same afternoon." According to Beatrice Campbell, when Gertler heard the news, "He was so shattered that he felt that nothing but a revolver could end his pain. He went out to buy one, but found it was Saturday afternoon and all the shops were shut." According to Beatrice Campbell, when Gertler heard the news, "He was so shattered that he felt that nothing but a revolver could end his pain. He went out to buy one, but found it was Saturday afternoon and all the shops were shut."

In January 1939 Mark Gertler separated from his wife. According to Gretchen Gerzina: "his marriage to Marjorie Hodgkinson was initially a happy one, although marred by ill health. He had tuberculosis, she a miscarriage; when their son Luke was born, he too had medical problems for some time. Mark found that family life was a disruption to his work, which was not going well. He loved his wife and son, but they agreed to separate for a while."

In May Gertler had his last exhibition. It was not a great success. Gertler wrote to Edward Marsh: "I'm afraid I am depressed about my show - I've sold only one so far... it's very disheartening." Marsh replied that he no longer liked Gertler's paintings. Gertler tried to explain his situation: "Obviously a number of other people feel as you do about my recent work... I can never set out to please - my greatest spiritual pleasure in life is to paint just as I feel impelled to do at the time... But to set out to please would ruin my process. The following month Gertler committed suicide in his studio.

Depressed by his ill-health and the the failure to sell more paintings, Gertler gassed himself in his studio at 5 Grove Terrace, Highgate Road, London, on 23rd June 1939 and was buried four days later in Willesden Jewish Cemetery.

Primary Sources

(1) (1)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

At the Slade, Mark was at first something of a misfit. He had started school late in life, and had left it at the age of fourteen. His hair was short and his clothes were different. Most of all, however, the other students found him too serious and too intense. He was extremely handsome, with huge dark eyes, pale skin, and a thin body, and he was both solemn and passionate about his art. Only at the polytechnic had he finally been introduced to museums and systematic schooling in the history of art, including the old masters. When he first arrived at the Slade at seventeen, he had the fervour of a convert who has surmounted great obstacles for his religion. In contrast, his fellow students seemed privileged and rather frivolous. Yet his early opinions of them were not untouched by envy.

(2) Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (7th July 1912)

In order to make you understand let me tell you for once always. You are no doubt extremely ignorant that way. Nature, forcibly takes hold of a man, places him on a road where she knows his ideal will pass. She passes: He loves her: madly, horribly, and uncontrollably. Not content with this, Nature implants him with a desire (no doubt for the sake of the preservation of the next generations) to wholly and absolutely honour that woman. This causes him to be jealous of everything she does with other people. He can't stand seeing her own mother kiss her, let alone another man. Of course as I said, it is not for me to tell you who to kiss or who not to kiss, nor will you take any notion of me if I did. The only thing is you mustn't tell me about these things as I can't bear it. I shall try and suffer quietly & alone in future though. Of course it is absurd to ask me to try and be friends with Nevinson, do you think I am made of stone? That I should be friends with the man who kisses my girl.

(3) Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (December, 1912)

Yes, my isolation is extraordinary. I am alone, alone in the whole of this world! Yes, if only like my brothers I was an ordinary workman as I should have been. But no! I must desire, desire. How I pay for those desires! Oh! God! Do I deserve to be so tormented? By my own ambitions I am cut off from my own family and class and by them I have been raised to be equal to a class I hate! They do not understand me nor I them. So I am an outcast. As I look at my desk I laugh, for there are dozens of notices of me in the daily papers, a lot of them praising my talents. Oh! yes I am quite well known, and yet alone.

(4) (4)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

During their absence from one another at this time the issue of their sexual relations - or more precisely, the lack of them - again was raised. Gertler felt that he had been more than patient and understanding during the last three years; it was time for her to put aside her girlish fears and have an adult relationship with him. She was, after all, nearly twenty-one-years old. In her turn, Carrington felt that he ought to accept her friendship on her terms. She raised no moral objections to sex, but felt herself absolutely incapable of such acts, and without any desire for them. They made her feel unclean and ashamed. Gertler tried to argue her down; since passion would not sway her, perhaps reason would.

(5) (5)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (2nd January 1914)

There can be no real friendship between us, as long as you allow that Barrier - Sex - to stand between us. If you care so much for my friendship, why not sacrifice, for a few moments, your distaste for Physical contact & satisfy me? Then we could be friends. Then I could love no one more than my friend - then I could share all with you.

I am doing work now, which is real work. Far better than anything I have done before & I would like you to share it with, but as long as that obsession for you sexually is there, I cannot. Remember I tried to fight it for three years, without success. Now it cannot go on any longer.... I am not ashamed of my sexual passion for you. Passion of that sort, in the case of love, is not lustful, but Beautiful!

(6) (6)Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (16th April 1915)

You wrote these last lines only a week ago, and now you tell me you were "hysterical and insincere".

Only I cannot love you as you want me to. You must know one could not do, what you ask, sexual intercourse, unless one does love a man's body. I have never felt any desire for that in my life: I wrote only four months ago and told you all this, you said you never wanted me to take any notice of you when you wrote again; if it was not that you just asked me to speak frankly and plainly I should not be writing. I do love you, but not in the way you want. Once, you made love to me in your studio, you remember, many years ago now. One thing I can never forget, it made me inside feel ashamed, unclean. Can I help it? I wish to God I could. Do not think I rejoice in being sexless, and am happy over this. It gives me pain also.

(7) Mark Gertler, letter to Edward Marsh (17th August, 1915)

I have come to the conclusion that we two are too fundamentally different to continue friends. Since the war, you have gone in one direction and I in another. All the time I have been stifling my feelings. Firstly because of your kindness to me and secondly I did not want to hurt you. I am I believe what you call a "Passivist". I don't know exactly what that means, but I just hate this war and should really loathe to help in it...

As long as I am not forced into this horrible atmosphere I shall work away. Of course from this you will understand that we had not better meet any more and that I cannot any longer accept your help. Forgive me for having been dishonest with you and for having under such conditions accepted your money. I have been punished enough for it and have suffered terribly. I stuck it so long, because it seemed hard to give up this studio which I love. But now rather than be dishonest I shall give it up and go to my cottage in the country. I have still a little money of my own from the Sadler portrait. On this I shall live. In the country I can live on £1 a week. I shall live there until there is conscription or until my money is used up.

Your kindness has been an extraordinary help to me. Since your help I have done work far, far better than before. I shall therefore never cease to be thankful to you. Also if I earn any money by painting I shall return you what I owe you. I shall send you the latchkey and please would you get Mrs Elgy to send me my pyjamas and slippers.

(8) (8)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

While Carrington was hard at work, Gertler was becoming even closer to Cannan. "He is a true man," he wrote in April. "There are not many like him. I like him truly. In the evenings we sit in the dimly lit mill, where he plays Beethoven to me and then we talk and talk." It was inevitable that Cannan, hearing so much about Gertler's life, would want to meet Carrington, and during 1914 she began to join Gertler on his weekend visits to Cholesbury.

Gertler also told Cannan about his artist friend John Currie, who was the cause of a major tragedy in October of that year. His lover, Dolly Henry (whose real name was O'Henry), had moved away from him and found rooms of her own in Paulton Square, Chelsea. Currie went there one evening and they had a terrible argument, in which he shot her and then turned the gun on himself. She died immediately, and he died later in the Chelsea Infirmary, under police guard. Gertler visited him in the Infirmary shortly before he died, and the whole sordid affair deeply affected him. Currie, seven years older than Gertler, had been a mentor to him. He had had little respect for private property, and used to help himself to whatever he desired, even though it might be in a friend's home. He had read Nietzsche earnestly, and had had great self-confidence. He had lived openly with Dolly, and the two of them had taken Gertler to Paris with them, initiating him into great art, petty lovers' quarrels, and foreign culture, all at first hand. As he had done with everything Gertler had told him, Cannan had made careful note of these events and had romanticised them in his fiction.

Through Gilbert Cannan and Eddie Marsh, Gertler was broadening his social horizons. Both moved in very different circles from his and while he did not always appreciate their friends, his growing reputation as an artist and entertaining guest made Gertler something of a social find. His and Carrington's introduction to the Bloomsbury group involved Marsh. In May 1914, Lady Ottoline Morrell, who with her husband Philip Morrell was becoming an important pacifist and patron of the arts at this time, wrote to invite Gertler and Carrington to a production of The Magic Flute. Gertler found that he had to break an appointment with Marsh in order to accept, "But I feel it is so difficult to refuse Lady Ottoline - then there is Carrington too." Having made the invitation, Lady Ottoline changed her plans, putting it off for a few days and "was not yet certain whether she can have us to dinner or not on that date". Behind the scenes Carrington and Gertler were reshuffling all of their plans in order to accommodate hers.

Lady Ottoline, a friend of Gilbert Cannan and half-sister to the Duke of Portland, had introduced herself to Gertler by visiting his studio home in Whitechapel. There she had been saddened by the low ceilings and his obvious poverty, but highly impressed by his work. She soon became his patron and champion, welcoming him (and later Carrington) to her houses in Bedford Square and at Garsington near Oxford. She remained his friend and ally, taking his side whenever Carrington frustrated him, but caring about both of them. They in turn defended her; she was easily caricatured because of her long nose, prominent chin and reddish hair, her sometimes heavy make-up, and flamboyant clothes, and many writers (including D. H. Lawrence in Women in Love) portrayed her cruelly in their works. Even her other friends and recipients of her generosity in Bloomsbury frequently made fun of her, which upset Carrington greatly.

(9) Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (27th February 1916)

The reason is that we both have different ways of reaching it. And the two ways are so different that they clash and fight and they always will clash and fight so that we shall therefore never be able to succeed together. Your way of reaching that state of spirituality is by leaving out sex. My way is through sex. Apparently we neither of us can change our ways, because they are ingrained in our natures. Therefore there will always be strife between us and I shall always suffer.

(10) D. H. Lawrence, wrote to Mark Gertler about seeing Merry-go-round (9th October, 1916)

I have just seen your terrible and dreadful picture Merry-go-round. This is the first picture you have painted: it is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great and true. But it is horrible and terrifying. If they tell you it is obscene, they will say truly. You have made a real and ultimate revelation.

I think this picture is your arrival - it marks a great arrival. Also I could sit down and howl beneath it like Kot's dog, in soul-lacerating despair. I realise how superficial your human relationships must be, what a violent maelstrom of destruction and horror your inner soul must be... You are all absorbed in the violent and lurid thing that makes leaves go scarlet and copper-green at this time of year. It is a terrifying coloured flame of decomposition... But dear God, it is a real flame enough, undeniable in heaven and earth. It would take a Jew to paint this picture. It would need your national history to get you here, without disintegrating you first. You are of an older race than I, and in these ultimate processes, you are beyond me, older than I am. But I think I am sufficiently the same, to be able to understand.

(11) Mark Gertler wrote about painting Merry-go-round on October, 1916.

I live in a constant state of over-excitement, so much do my work and conception thrill me. It is almost too much for me and I am always feeling rather ill. Sometimes after a day's work I can hardly walk.

(12) Roger Fry, letter to Vanessa Bell on the work of Mark Gertler (6th October, 1917)

What he has to express is not, it must be confessed, of the highest quality, because his reactions are limited and rather undistinguished. He has only two or three notes, and they are neither rich nor rare. For an artist he is unimaginative, and often in their blank simplicity his conceptions are all but commonplace. Though a first-rate craftsman who paints admirably, he lacks sensibility.

(13) Mark Gertler, letter to Dora Carrington (20th February, 1918)

I am a complex being; there are many bad sides to my nature; but my real flame always burns brightly, and no wind or hurricane, ever can extinguish it.

(14) Virginia Woolf, diary entry describing Mark Gertler (10th September, 1918)

His face is a little tight and pinched; but the word he would wish one to use of him is powerful. His mind certainly has a powerful spring to it. He is also evidendy an immense egoist. He means by sheer willpower to conquer art. But bating this sort of aggression he was well worth talking to. Leonard noticed his amazing quickness. He would soon have told us the story of his life. I felt about him, as about some women, that unnatural repressions have forced him into unnatural assertions.

(15) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

Carrington's family situation eased slightly in 1914 when the Carringtons moved to a Georgian farmhouse in Hurstbourne Tarrant, Hampshire. There were enough outbuildings for Carrington to have her own studio, and here she began her love affair with the landscapes and scenery of the countryside, first capturing the view from her top-floor bedroom in an evocative watercolour entitled Hill in Snow at Hurstbourne Tarrant (1916).

The other love affair that began at this time was with a fellow student, Mark Gertler, whom Carrington had met at the Slade just before graduating. Their twelve-year long friendship, which started so optimistically with shared trips to galleries and exhibitions, became troubled very quickly and caused both of them much unhappiness. Although passionate towards Gertler when discussing art, Carrington, at eighteen, had not yet had her sexuality awakened; her upbringing had taught her to repress her innermost feelings. She was looking for a platonic soul mate, but what she found was a man who was highly sexed and constantly irritated and frustrated by Carrington's lack of passion. The heartbreaking letters that passed regularly between them pay sad testimony to the anguish that this long relationship caused. On graduating from the Slade, Carrington had fallen into an unhappy, confused state. She was unsure of her own identity, haplessly seeking somebody who would restore it to her. That somebody, a fellow guest at Virginia Woolf's country home, Asheham, was to be Lytton Strachey.

(16) Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey (1994)

He (Mark Gertler) did not know where he was, and in his bafflement began discussing his troubles with D.H. Lawrence, Gilbert Cannan, Aldous Huxley, Ottoline Morrell and others. So he and Carrington were to find their way into the literature of the times. In Aldous Huxley's Crome Yellow (1921) Gertler becomes the painter Gombauld, "a black-haired young corsair of thirty, with flashing teeth and luminous large dark eyes"; while Carrington may be seen in the "pink and childish" Mary Bracegirdle, with her clipped hair "hung in a bell of elastic gold about her cheeks", her "large china blue eyes' and an expression of "puzzled earnestness". In D.H. Lawrence's Women in Love (1921), some of Gertler's traits are used to create Loerke, the corrupt sculptor to whom Gudrun is attracted (as Katherine Mansfield was to Gertler), while Carrington is caricatured as the frivolous model Minette Darrington - and Lytton too may be glimpsed as the effete Julius Halliday. Lawrence became fascinated by what he heard of Carrington. Resenting the desire she had provoked and refused to satisfy in his friend Gertler, he took vicarious revenge by portraying her as Ethel Cane, the gang-raped aesthete incapable of real love, in his story None of That. "She was always hating men, hating all active maleness in a man. She wanted passive maleness." What she really desired, Lawrence concluded, was not love but power. "She could send out of her body a repelling energy," he wrote, "to compel people to submit to her will." He pictured her searching for some epoch-making man to act as a fitting instrument for her will. By herself she could achieve nothing. But when she had a group or a few real individuals, or just one man, she could "start something", and make them dance, like marionettes, in a tragi-comedy round her. "It was only in intimacy that she was unscrupulous and dauntless as a devil incarnate," Lawrence wrote, giving her the paranoiac qualities possessed by so many of his characters. "In public, and in strange places, she was very uneasy, like one who has a bad conscience towards society, and is afraid of it. And for that reason she could never go without a man to stand between her and all the others."

(17) Mark Gertler, letter to Dorothy Brett (November, 1918)

It is not the fear of starving or anything as simple as that, that haunts me. It is the general principle. I long to be free and independent for my living, both from people and my work. To have to think of selling pictures, all the time and to tolerate silly people coming up here to see them, is awful. It creeps into all one's moods and spoils everything.

(18) Mark Gertler, letter to Ottoline Morrell (7th May, 1924)

I believe my age to be a critical one -I feel from now to forty to be, as it were, my last chance - the last chance to justify my existence - to really learn how to live and to achieve something. If I don't do it by the next 10 years I am done for.

(19) Mark Gertler, letter to Edward Marsh (May, 1939)

Obviously a number of other people feel as you do about my recent work... I can never set out to please - my greatest spiritual pleasure in life is to paint just as I feel impelled to do at the time... But to set out to please would ruin my process - and you know me well enough to realize that I am sincere - and to paint to the best of my capacity is and has always been my primary aim in life - I have sacrificed much by doing so... You must remember that many works by artists of the past were considered unattractive during their life time - there is just a chance that some of my works may be more appreciated in the future.

(20) Richard Shone, review of Mark Gertler (6th July, 2002)

This book (Mark Gertler by Sarah MacDougall) tells a tragic story in which youthful success counts as one of the chief instruments of destruction. Mark Gertler achieved renown as a painter in the years before the first world war. He was a star turn at the Slade School of Art in London, where his contemporaries included Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, CRW Nevinson and David Bomberg. He was petted and feted, attracted discriminating patrons and became the toast of Upper Bohemia.

Twenty-five years later, just before the start of the second world war, he pushed a mattress against the door of his London studio and gassed himself. He was 47 years old. "With his intellect and interest," Virginia Woolf asked in her diary, "why did the personal life become too painful?"

From a reading of this book, several explanations emerge - a failed marriage, burdensome debts, the continuing struggle against tuberculosis and clinical depression, and a faltering reputation as a painter. It also becomes clear that Gertler was his own worst enemy, and his suicide was the culmination of a pattern of self-destructive acts.

To a wider public now, Gertler is known for his passionate attachment to the painter Dora Carrington. For 10 years, from when he met her as a fellow student at the Slade School of Art, he loved the wrong woman, a relationship recorded in letters that are terrible to read, that smouldered on even after Carrington had set up home with Lytton Strachey.

He is also known for his part in the lives of writers such as DH Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield and Aldous Huxley (he is the model for the painter, Gomauld, in the latter's Crome Yellow); as Lady Ottoline Morrell's artist-in-residence at Garsington Manor; and for a single, much-reproduced work of 1916: The Merry-Go-Round (currently hanging in Tate Britain).

With its acidic comment on the herd mentality of the first-world-war period, this prescient image of robotic uniformity retains its power, but it is in fact Gertler's least typical painting. In his maturity, his more usual subjects were the stuff of Parisian modernism - pneumatic nudes, views through windows, still lifes with guitars, fruit and flowers. But none quite matches in intensity either The Merry-Go-Round or the early figures and portraits taken from the life he knew in the Jewish quarter of London's East End, where he had been born.