Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy, the first of the four children of Thomas Hardy (1811–1892) and and his wife, Jemima (1813–1904), was born in Upper Bockhampton, near Dorchester, on 2nd June 1840. His father was a stonemason and jobbing builder.

According to his biographer, Michael Millgate: "As a sickly child, not confidently expected to survive into adulthood and kept mostly at home, Hardy gained an intimate knowledge of the surrounding countryside, the hard and sometimes violent lives of neighbouring rural families, and the songs, stories, superstitions, seasonal rituals, and day-to-day gossip of a still predominantly oral culture."

At eight Hardy went to the new national school in local school in Bockhampton. His mother was determined that he had a good education, and after a year arranged for him to study Latin, French and German at a nonconformist school in Dorchester. This involved a 3 miles walk, twice daily for several years.

At the age of 16 Hardy he was articled to John Hicks, an architect. During this period he became friends with Horace Moule, the socialist son of Horace Moule and evangelical vicar in Fordington. Moule was eight years older than Hardy. Moule has been described as "a charming and gentle man as well as a brilliant teacher". Moule also introduced him to socialism and to the radical ideas being expressed in the Saturday Review. Edited by John Douglas Cook, it attributed the majority of social evils to social inequality. Hardy became a great admirer of Percy Bysshe Shelley for his "genuineness, earnestness, and enthusiasms on behalf of the oppressed".

Once qualified, he moved to London and found work with a company that specialized in church architecture. In his spare-time he continued his education with visits to the theatre, opera and art galleries. It was at this time he began to write poetry, and although he submitted them to several magazines, they were all rejected.

In April 1862, Hardy left Dorchester for London, where he quickly found work as a draughtsman in the office of the successful architect, Arthur William Blomfield. Hardy was elected to the Architectural Association, and won in 1863 the silver medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects for an essay entitled On the Application of Coloured Bricks and Terra Cotta to Modern Architecture.

Hardy wanted to become a novelist. He received considerable support from his friend, Horace Moule, in achieving his objective. However, progress was slow. On 2nd June 1865, he wrote in his diary: "Feel as if I had lived a long time and done very little. Wondered what woman, if any, I should be thinking about in five years' time."

At about this time he became attached to his cousin, Tryphena Sparks, a student teacher from Puddletown, who was eleven years his junior. Tryphena was the daughter of Hardy's mother's sister. As Claire Tomalin, the author of Thomas Hardy: The Time Torn Man (2006) has pointed out: "Cousins could be a heaven sent answer to the need for emotional experiment and sexual adventure in Victorian England. They were accessible, flirtable with, almost sisters, part of the family, and, indeed, in many families marriages took place between cousins. So it is likely that Tom throughly enjoyed the company of all his girl cousins, flirted with them and made as much love to them as he could get away with when he had the chance... She was clever and pretty... and it seems that a warm cousinly affection developed as they got to know one another better."

In her book, Providence and Mr Hardy (1966), Lois Deacon argued that Tryphena gave birth to Hardy's illegitimate son. Robert Gittings, the author of The Young Thomas Hardy (2001) has argued that there is no real evidence for this claim: "What is certain is that Hardy became involved in some way with Tryphena... What passed between them... is difficult to say". Hardy's biographer, Michael Millgate, agrees with Gittings, and was unable to find any evidence of a child "capable of withstanding scholarly or even common-sensical scrutiny". However, he adds: "The two were often alone together, and it would not be extraordinary if they made love. But there was certainly no child, probably no formal engagement". The relationship came to an end when Hardy became engaged to Emma Gifford.

Ill-heath forced Hardy to return to his parent's home in the summer of 1867. After he recovered he decided against returning to London and resumed work with local architect, John Hicks. He also began work on his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady. The story tells of the love and marriage of a young architect and the daughter of a large local landowner. According to Hardy: "The story was, in fact, a sweeping dramatic satire of the squirearchy and nobility, London society, the vulgarity of the middle class, modern Christianity, church restoration, and political and domestic morals in general, the author's views, in fact, being obviously those of a young man before and after him, the tendency of the writing being socialistic and revolutionary."

Hardy sent the manuscript to his friend, Horace Moule, who arranged for it to be read by publisher, Alexander Macmillan. He replied that although he liked some aspects of the novel he disliked was he considered to be an excessive attack on the upper classes.

Macmillan suggested that Hardy should approach Frederick Chapman of publishers Chapman and Hall, who were the current publishers of Charles Dickens. He agreed to publish The Poor Man and the Lady, but only if he paid the publishers the sum of £20 to cover any losses which the firm might incur by publishing the book.

Hardy then sent the manuscript to George Meredith. He replied that the book would be perceived as "socialistic" or even "revolutionary" and that as a result would not be well-received by the critics. Meredith went onto argue that this might prove to be handicap to Hardy's future career. He suggested that Hardy should either rewrite the story or write another novel with a different plot.

John Hicks died in 1868. Hardy now went to work for G.R. Crickmay, an architect in Weymouth. In March 1870 Hardy was sent to St. Juliot near Boscastle, by Crickmay, in order "to take a plan and particulars of a church I am about to rebuild there". While in the village Hardy met Emma Gifford, the daughter of a wealthy solicitor. She later recalled that Hardy had a beard and was wearing "a rather shabby great coat". Hardy fell in love with Emma and he returned to the village every few months. During this period Emma was described as having "a rosy, Rubenesque complexion, striking blue eyes and auburn hair with ringlets reaching down as far as her shoulders".

Robert Gittings, the author of The Young Thomas Hardy (2001) has argued: "Emma Lavinia Gifford certainly appears... as the spoilt child of a spoilt father. There is no doubt at all that wilfulness and lack of restraint gave her a dash and charm that captivated Hardy from the moment they met. He did not consider, any more than most men would have done, that a childish impulsiveness and inconsequential manner, charming at thirty, might grate on him when carried into middle age."

Later that year he sent Desperate Memories to Alexander Macmillan. He passed it to John Morley, the editor of The Fortnightly Review. Morley said the story was "ruined by the disgusting and absurd outrage which is the key to its mystery: the violation of a young lady at an evening party, and the subsequent birth of a child". Macmillan took Morley's advice and rejected the novel.

Hardy then approached the publishers, Tinsley Brothers. After he agreed to make changes they offered to publish the book if he paid them £75. Although he only had savings of £123 he agreed to the terms of the deal. Desperate Memories was published anonymously on 25th March 1871. It received some good reviews but was severely attacked in The Spectator, which condemned the author for "idle prying into the ways of wickedness". The book was not a commercial success and most of the 500 copies were remaindered and Hardy lost £15 in the venture.

Hardy was determined to continue with his writing career and his next novel, Under the Greenwood Tree, was based on his own childhood. Throughout his career he invented his own names for the real-life places. For example, Casterbridge (Dorchester), Weatherbury (Puddletown), Budmouth Regis (Weymouth), Sandbourne (Bournemouth), Wintonchester (Winchester), Trantridge (Pentridge) and Knollsea (Swanage). When the book was rejected by Alexander Macmillan, he came close to giving up his ambition to become a full-time writer. However, Emma Gifford, who was convinced of his talent, urged him to send the manuscript to other publishers.

Under the Greenwood Tree was published by Tinsley Brothers in June 1872. After good reviews in the Pall Mall Gazette and The Athenaeum, it was agreed to serialise the novel over a period of twelve months in the Tinsley's Magazine. This gave Hardy a guaranteed income over the next year and he decided he could take the risk of becoming a full-time writer. Emma Gifford, despite the objections of her father, agreed to marry Hardy.

Hardy next novel, A Pair of Blue Eyes, was inspired by his relationship with Emma. The story tells of Stephen Smith, an architect and the son of a stonemason, who is sent to Cornwall to work on the restoration of a church. Here he meets and falls in love with Elfride Swancourt. Smith's friend, Henry Knight (based on Horace Moule), a barrister, also loves Elfride. Smith also attempts to conceal from Elfride that he had previously loved another woman (Tryphena Sparks). The first installment appeared in Tinsley's Magazine in September 1872.

On 21st December, 1873, Horace Moule was staying with his brother, Charles Moule. When he heard a strange noise in an adjoining room, Charles discovered that Horace had slashed his windpipe with a razor. He was covered in blood but conscious and was able to utter his last words "Easy to die. Love to my mother." Andrew Norman, the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011) has argued: "He (Moule) had befriended Hardy; encouraged him with gifts of books and intellectually stimulating conversations; set him on the road to socialism, and shielded and defended him when his books were denigrated by other critics. But for years Moule, a taker of opium and a heavy drinker, had battled against severe depression and suicidal tendencies, and at the end of the day, Hardy's great friend and comrade had been unable to overcome his problems. what was it that had brought the two of them so closely together? Perhaps in Hardy, Moule recognised a kindred spirit: a person, like himself, of great sensitivity, who saw enormous suffering in the world and found it hard to bear."

Leslie Stephen, the editor of The Cornhill Magazine, had been impressed by Hardy's Under the Greenwood Tree and asked him to provide a story suitable for serialisation in the magazine. Hardy accepted the offer and began work on a story that had been told to him by his former girlfriend, Tryphena Sparks. It tells of a woman who has inherited a farm, which contrary to the tradition of the times she insists on managing herself.

Far From the Madding Crowd is the story of a young woman-farmer, Bathsheba Everdene, and her three suitors: Gabriel Oak, a young man who owns a small sheep farm. Sergeant Frank Troy, a well-educated, young soldier who has a reputation as a womaniser. William Boldwood, a local farmer who develops a strong passion for Bathsheba. Leslie Stephen was shocked by the sexual content of the novel and asked for Hardy to make some changes, admitting that this was the result of "an excessive prudery of which I am ashamed."

The novel was serialised between January and December 1874. After receiving £400 by its publishers, Hardy could now afford to marry Emma Gifford. The wedding took place on 17th September 1874. Emma's uncle, Dr Edwin Hamilton Gifford, canon of Worcester Cathedral officiated. The only other people present being Emma's brother, Walter E. Gifford and Sarah Williams, the daughter of Hardy's landlady, who signed the register as a witness. Hardy's parents, may have also objected to the marriage because they were not invited to the ceremony.

After spending a few days in Brighton they travelled to Paris, where Hardy insisted on visiting the city mortuary where he looked at several dead bodies. Emma wrote in her diary that she found the experience "repulsive". According to the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011): "The visit to the Paris mortuary had led to speculation that Hardy may have had a tendency to necrophilia (a morbid, and in particular an erotic, attraction to corpses)".

The success of Far From the Madding Crowd meant that he was commissioned to write another novel for The Cornhill Magazine. He decided to write a light-hearted satirical comedy, The Hand of Ethelberta. He told Leslie Stephen that it "would concern the follies of life" and he would tell it "in something of a comedy form, all the characters having weaknesses at which the superior lookers-on smile, instead of being ideal characters". It was serialized in the journal between July 1875 and May 1876. It was poorly received and Hardy was never again invited to write a serial for the journal.

The failure of The Hand of Ethelberta meant that Hardy had difficulty finding a magazine to serialise his next novel, The Return of the Native. Eventually, Belgravia, a magazine best known as an outlet for "sensation" fiction, agreed to take the novel. The first part appeared in January 1878. It was again not well-received and Hardy decided that he would try writing for a more popular audience. This included The Trumpet-Major (1880), A Laodicean (1881) and Two on a Tower (1882).

In 1883 the Hardys moved to a rented house in Dorchester. He commissioned Hardy's father and brother to build a new house just outside the town, on a plot of open downland on the road to Wareham. Called Max Gate, the red-brick building was completed in June 1885. Hardy planted over 2,000 trees around it to give him greater privacy. However, he wrote in his diary at the end of the year that he was "sadder than many previous New Year's Eves have done." He also said that the building of his new home was not "a wise expenditure of energy".

Hardy completed his novel, The Mayor of Casterbridge, in April 1885. The story tells of Michael Henchard, a hay-trusser, arrives at Weydon Fair in search of work. While under the influence of alcohol he puts his wife Susan, together with their child Elizabeth Jane, up for auction. Mother and daughter are purchased by a sailor. The next day Henchard bitterly regrets his action and vows to abstain from drink for a period of twenty years. Henchard moves to Casterbridge where he becomes a successful corn merchant. Much respected he become the town's mayor. However, years later, Susan arrives in Casterbridge with the news that her sailor husband is now dead. Henchard remarries Susan but this is the beginning of a series of problems that results in his ignoble death.

The Mayor of Casterbridge was published on 10th May 1886. The book had mixed reviews and he wrote to Edmund Gosse complaining about how so many of the reviews were anonymous: "The crown of my bitterness has been my sense of unfairness in such impersonal means of attack". He went onto argue that these attacks mislead the public into thinking that there is "an immense weight of opinion" behind these views. The book was serialized in the weekly Graphic between 2nd January and 5th May 1886.

Hardy's next novel was The Woodlanders. He wrote in the novel's preface that the book is principally concerned with the "question of matrimonial divergence, the immortal puzzle of how a couple are to find a basis for their sexual relationship". He then adds that a problem may arise when a person "feels some second person to be better suited to his or her tastes than the one whom he has contracted to live". It has been argued that the book deals with Hardy's relationship with his wife.

Andrew Norman, the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011) has pointed out: "In The Woodlanders, many of Hardy's favourite themes resurface. They include the problems encountered when two persons of different social status fall in love, and when two men compete with one another for the hand of one woman, together with the problems men and women may have of understanding one another. Hardy also stresses that qualities such as loyalty, devotion and steadfastness in a male suitor, ought always to triumph over wealth, property and title." The Woodlanders was serialized in Macmillan's Magazine from May 1886 to April 1887.

On 4th May 1888, a book of short-stories, Wessex Tales, was published by Alexander Macmillan. The volume contained five stories, The Three Strangers, The Withered Arm, Fellow-Townsmen, Interlopers at the Knap and The Distracted Preacher. In a later edition Hardy added a sixth story, An Imaginative Woman.

Hardy's cousin, Tryphena Sparks, married Charles Frederick Gale, the proprietor of a public house in Topsham, Devon. She suffered from ill-health and died three days before her 39th birthday, on 17th March, 1890. On hearing of her death Thomas Hardy wrote Thoughts of Phena. The poem begins with the words: "That no line of her writing have I. Nor a thread of her hair." Hardy goes on to recall her as "my lost prize".

Hardy next novel was Tess of the D'Urbervilles. The story starts with Parson Tringham, telling Jack Durbeyfield, an impoverished farm labourer, that he is descended from the "ancient and knightly family of the D'Urbervilles". Durbeyfield discovers that there is a rich family with the name of D'Urbervilles, is living in a large house in nearby Trantridge. He sends his daughter Tess, to pay the family a visit, with the purpose of claiming kinship to them.

Tess is given a job managing the family poultry farm. One night, while she is sleeping, Alec D'Urberville, the son of the owner of the house, rapes her and she falls pregnant. He also tells her that the family are not genuine D'Urbervilles but have purchased the name and title.

Tess returns to her village to have the baby but it dies soon afterwards. Tess then finds employment with a local farmer. While at work she meets Angel Clare. They fall in love and they eventually marry. He later confesses that he has had a previous relationship with another woman. She also confesses to her relationship with Alec D'Urberville. Angel is so shocked by the news he decides to emigrate to Brazil.

Alec discovers what has happened and offers to marry Tess. She declines because she does not love him. However, she does agree to live with him. Angel eventually returns from Brazil and asks her forgiveness. Tess says it is too late as she is now living with Alec. A distraught Angel catches the train home, only to have Tess jump into the carriage with the news that she hopes she has won his forgiveness by murdering the man who ruined both their lives. They live with each other for five days before Tess is arrested by the police. The novel closes with Tess being executed at Wintonchester Prison.

Tess of the D'Urbervilles was published in November 1891. Several libraries refused to stock the book but the controversy about the content helped it to become a best-seller. It was also translated into several different languages. Hardy was upset with the reviews that the book received that he said to a friend that "if this sort of thing continues" there would be "no more novel writing for me."

During this period Hardy was very depressed. He told his friend, Edmund Gosse: "You would be quite shocked if I were to tell you how many weeks and months in byegone years I have gone to bed never wishing to see daylight again." When another friend, Rider Haggard, lost one of his children to illness, he wrote: "Please give my kind regards to Mrs Haggard, and tell her how deeply our sympathy was with you both on your bereavement. Though, to be candid, I think the death of a child is never really to be regretted, when one reflects on what he has escaped."

Despite these comments, Hardy now began work on what was to be his most controversial book, Jude the Obscure. Following the death of his parents, Jude Fawley, is brought up by a great aunt, who, along with his schoolmaster, Phillotson, encouraged him to get a university education at Christminster (Oxford). However, before he can do this he is tricked into marrying Arabella Donn, the daughter of a pig breeder.

Arabella eventually deserts Jude and goes to live in Australia. Jude moves to Christminster where he obtains employment as a stonemason, while continuing to study part-time. Unfortunately, his application to study at the university is rejected.

While in Christminster he becomes friendly with his cousin, Sue Bridehead. He introduces her to Phillotson, whom she subsequently marries. However, the marriage is not a success and as she is so unhappy, Phillotson agrees to give Sue a divorce. For this act of compassion, Phillotson is dismissed from his post as schoolmaster.

Sue goes to live with Jude and they consider getting married. Jude is dissatisfied with Sue because she is "such a phantasmal, bodiless creature, one who - if you'll allow me to say it - has so little animal passion in you, that you can act upon reason in the matter when we poor unfortunate wretches of grosser substance can't." Jude tells Sue: "People go on marrying because they can't resist natural forces, although many of them may know perfectly well that they are possibly buying a month's pleasure with a life's discomfort."

Jude and Sue eventually agree to get married, but when they arrive at the registrar's office, Sue changes her mind and says to Jude: "Let us go home, without killing our dream". However, they do live together and Sue gives birth to two children. Jude is informed by Arabella that after leaving him she gave birth to his son. She asks him to look after the son, Juey. Jude and Sue agree to this suggestion.

Jude is employed by the local church to inscribe stone tablets. When it is discovered that Jude and Sue are unmarried, he is sacked from his job. Soon afterwards, Juey, hangs Jude's two children by Sue and then hangs himself. Sue regards this as a judgement from God and returns to Phillotson.

In the preface of Jude the Obscure Hardy point out that the novel is about the "tragedy of unfulfilled aims". He then goes onto argue that it was an attempt to confront the issue of "the fret and fever, derision and disaster, that may press in the wake of the strongest passion known to humanity; to tell, without a mincing of words, of a deadly war waged between flesh and spirit." Hardy admitted that the novel was an attack on the marriage laws. He wrote that "a marriage should be dissolvable as soon as it becomes a cruelty to either of the parties - being then essentially and morally no marriage."

Michael Millgate, the author of Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisted (2006) has argued: "Its haunted characters, trapped within an intricately disastrous plot, move restlessly from one unfriendly town to another, loving without fulfillment, striving without achievement. By representing Jude Fawley as encountering persistent persecution in his attempts to gain admission to a Christminster (that is, Oxford) college and share with Sue Bridehead a life outside wedlock, Hardy was deliberately attacking the existing educational system and marriage laws."

Reviewers were shocked by the sexual content of the book and it was described as "Jude the Obscene" and "Hardy the Degenerate". William How, the Bishop of Wakefield announced that he was so appalled by Jude the Obscure that he had thrown the novel into the fire. Hardy responded that there was a long religious tradition of "theology and burning" and suggested "they will continue to be allies to the end". Although the novel sold over 20,000 copies in three months, Hardy was upset by the reviews the book received. He commented that he had reached "the end of prose" and now concentrated on writing poetry.

Hardy admitted to a close friend that the characters, Jude and Sue, were based on himself and his wife Emma. As Andrew Norman has pointed out: "Emma felt the same way as Hardy's fictitious character Sue Bridehead, who confessed that the idea of falling in love held a greater attraction for her than the experience of love itself; that Emma, like Sue, derived a perverse pleasure from seeing her admirers break their hearts over her; that Emma felt the same physical revulsion for Hardy that Sue had felt for Phillotson."

Hardy's biographers have speculated that the marriage was never consummated. Emma Hardy complained that her husband never understood her needs. "I can scarcely think that love proper, and enduring, is in the nature of men. There is ever a desire to give but little in return for our devotion and affection." In a letter she wrote in November, 1894, Emma complained that Hardy "understands only the women he invents - the others not at all."

Claire Tomalin has argued that Hardy was partly responsible for the bad relationship with his wife: "Thomas Hardy was not a good husband, self-centred to the point of cruelty, self-concealing, touchy and mean... It is a hard truth that men of genius may have bad characters, as Robert Gittings (Hardy's biographer) shows Hardy had." As Emma pointed out he provided "neither gratitude nor attention, love, or justice, nor anything you may set your heart on."

Emma was particularly upset with his platonic relationship with Florence Henniker. Nor did she like his closeness to his sister, Mary. In a letter written to Mary in February 1896 she claimed: "Your brother has been outrageously unkind to me - which is entirely your fault: ever since I have been his wife you have done all you can to make division between us; also, you have set your family against me, though neither you nor they can truly say that I have ever been anything but just, considerate, and kind towards you all, notwithstanding frequent low insults... You have ever been my causeless enemy - causeless, except that I stand in the way of your evil ambition to be on the same level with your brother by trampling, upon me... doubtless you are elated that you have spoiled my life as you love power of - any kind, but you have spoiled your brother's and your own punishment must inevitably follow - for God's promises are true for ever."

Another source of conflict was Emma devout religious views. Hardy on the other hand gradually lost his religious faith. He wrote to a friend that he had been searching for God for fifty years "and I think that if he had existed I should have discovered him". Emma donated money to various Christian charitable institutions, including the Salvation Army and the Evangelical Alliance. She also paid for religious pamphlets to be printed, which she left in local shops or at the homes of people she visited. She wrote that her objective was to "help to make the clear atmosphere of pure Protestantism in the land to revive us again - in the truth - as I believe it to be".

Emma Hardy especially disliked the anti-religious views expressed in Jude the Obscure. Hardy's biographer, Michael Millgate, has pointed out: "Emma Hardy took personal offence not only at Jude's attack on marriage but also at what she saw as its dark pessimism and irreligiousness... As a professional novelist writing to deadlines, peremptory as to his priorities and impatient of interruptions, he was not easy to live with, and he had failed - had perhaps not sufficiently tried - to resolve the antagonism between his wife and the family he now regularly visited. Emma Hardy, temperamentally restless and impulsive, lacking satisfying occupations and sympathetic friends, grew ever more deeply resentful - and publicly critical - of her husband's self-sufficiency and fame."

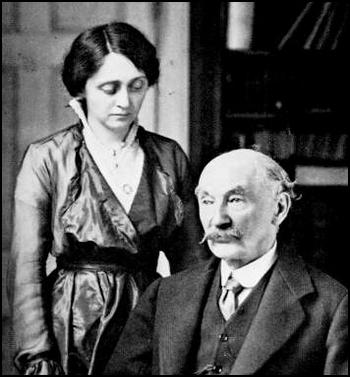

In 1904 Hardy was introduced to a 25-year-old female schoolteacher, Florence Emily Dugdale. Hardy was attracted to Florence and invited her to help him with the research for his latest project, The Dynasts: A Drama of the Napoleonic Wars. As the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011) has pointed out: "The Dynasts is the longest dramatic composition in English literature. It is an historical narrative, written mainly in blank verse, but also in other metres and in prose, featuring France's Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte".

Hardy was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1907 he and Emma Hardy joined George Bernard Shaw and his wife, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, in a march led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett and the National Union of Suffrage Societies in London. He also corresponded with feminists such as Marie Stopes and Evelyn Sharp.

Several visitors to Max Gate commented on the strange behaviour of Emma Hardy. Florence Emily Dugdale wrote to her friend Edward Clodd in November 1910: "Mrs Hardy seems to be queerer than ever. She has just asked me whether I have noticed how extremely like Crippen, Thomas Hardy is in personal appearance. She added darkly, that she would not be surprised to find herself in the cellar one morning. All this in deadly seriousness."

The writer, Arthur C. Benson met her for the first time in September, 1912. He wrote in his diary: "Mrs Hardy is a small, pretty, rather mincing elderly lady with hair curiously puffed and padded and rather fantastically dressed. It was hard to talk to Mrs Hardy who rambled along in a very inconsequentional way, with a bird-like sort of wit, looking sideways and treating my remarks as amiable interruptions... It gave me a sense of something intolerable the thought of his having to live day and night with the absurd, inconsequent, huffy, rambling old lady. They don't get on together at all. The marriage was thought a misalliance for her, when he was poor and undistinguished, and she continues to resent it... He (Hardy) is not agreeable to her either, but his patience must be incredibly tried. She is so queer, and yet has to be treated as rational, while she is full, I imagine, of suspicions and jealousies and affronts which must be half insane."

Evelyn Evans, a member of the Dorchester Debating Literary and Dramatic Society, was a regular visitor to Hardy's home. She later recalled: "She (Emma Hardy) was considered very odd by the townspeople of Dorchester... Her delusions of grandeur grew more marked. Never forgetting that she was an archdeacon's niece who had married beneath her.. She persuaded embarrassed editors to publish her worthless poems, and intimated that she was the guiding spirit of all Hardy's work."

In one letter Emma Hardy described Hardy as "utterly worthless". Thomas Hardy's assistant, Florence Emily Dugdale, remarked that he "spent long evenings alone in his study, insult and abuse his only enlivenment. It sounds cruel to write like that, and in atrocious taste, but truth is truth, after all."

Christine Wood Homer was another regular visitor to Max Gate. She claims that Emma Hardy "had the fixed idea that she was the superior of her husband in birth, education, talents, and manners. She could not, and never did, recognise his greatness". As she got older he behaviour became stranger: "Whereas at first she had only been childish, with advancing age she became very queer and talked curiously." Emma's cousin, Kate Gifford, wrote to Hardy saying "it must have been very sad for you that her mind became so unbalanced latterly".

Even in his seventies Hardy spent hours riding his bicycle. He argued that the advantage of possessing a bicycle was that you could travel a long distance "without coming in contact with another mind - not even a horse, and in this way there was no danger of dissipating one's mental energy."

On Hardy's 72nd birthday, he was visited by the poets Henry Newbolt and W. B. Yeats. Newbolt later recalled: "Hardy, an exquisitely remote figures, with the air of a nervous stranger, asked me a hundred questions about my impressions of the architecture of Rome and Venice, from which cities I had just returned. Through this conversation I could hear and see Mrs. Hardy giving Yeats much curious information about two very fine cats... In this situation Yeats looked like an Eastern Magician overpowered by a Northern Witch - and I too felt myself spellbound by the famous pair of Blue Eyes, which surpassed all that I have ever seen."

On 22nd November, 1912, Emma Hardy felt unwell. She was visited by her doctor who pronounced that the illness was not of a serious nature. However, on the morning of 27th November, the maid found her dead in bed. Soon after the funeral, Hardy discovered two "book-length" manuscripts, The Pleasures of Heaven and the Pains of Hell and What I Think of My Husband. After reading them Hardy burnt them in the fire.

After the death of his wife, Hardy saw a great deal more of Florence Emily Dugdale. Hardy married the 35-year-old Florence, on 10th February 1914, at St. Andrew's Church in Enfield. The couple did not have a honeymoon, but returned to Max Gate. Hardy, who was approaching his 74th birthday. Hardy described Florence as a "tender companion". However, the parlour-maid Ellen Titterington, commented that the couple "occupied separate bedrooms with a common dressing-room between."

Andrew Norman, the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011) has argued: "Florence Emily Hardy was, in many ways, the complete antithesis of Emma, and in consequence, the changes which she brought about to Hardy's life were truly remarkable... Florence did all in her power to make Hardy's life bearable." She wrote to a friend: "I think he really needs affection and tenderness more than anyone I know - life has dealt him some cruel blows."

Florence wrote to Edward Clodd about life with Thomas Hardy: "His life here is lonely beyond words, and he spends his evenings in reading and re-reading voluminous diaries that Mrs H. has kept from the time of their marriage. Nothing could be worse for him. He reads the comments upon himself - bitter denunciations, beginning about 1891 and continuing until within a day or two of her death - and I think he will end by believing them." Florence told another friend that she felt towards him "as a mother towards a child with whom things have somehow gone wrong - a child who needs comforting - to be treated gently and with all the love possible."

Although he gave up writing novels after Jude the Obscure Hardy continued to write poems. He would sit at his writing-table every morning at 10 a.m. If the spirit moved him, he would write; if it did not, he would find something else to do. He published several volumes of poetry during his last years, including Moments of Vision (1917), Late Lyrics (1922), Human Shows (1925) and Winter Words (1928). He also corresponded with many of the outstanding writers of the period including Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, E. M. Forster, J. B. Priestley, H.G. Wells and John Galsworthy.

On 25th December, 1927, Hardy wrote to his friend, Edmund Gosse: "I am in bed on my back, living on butter-broth and beef tea, the servants being much concerned at my not being able to eat any Christmas pudding."

Thomas Hardy never recovered from this last illness and died aged 87 on 11th January 1928. Hardy's ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey in Poets' Corner on 16th January. The last novelist to be buried there prior to this was Charles Dickens in 1870.

Primary Sources

(1) Andrew Norman, Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011)

In The Woodlanders, many of Hardy's favourite themes resurface. They include the problems encountered when two persons of different social status fall in love, and when two men compete with one another for the hand of one woman, together with the problems men and women may have of understanding one another. Hardy also stresses that qualities such as loyalty, devotion and steadfastness in a male suitor, ought always to triumph over wealth, property and title.

(2) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

The chief impression left on my mind is of the interesting house party at Mr. Clodd's. Besides M. Huchon and Clement Shorter and his wife (Dora Sigerson the poet), Henry Nevinson and Thomas Hardy were both there. I had already met Hardy in town, one afternoon at tea, and remember his saying, in answer to a question, that he did not find people on the whole much more brilliant in London than in Dorset. " At first," he said, " you think, when someone says something that is new to you, "How clever!" Then, wherever you go, you find everybody else saying the same thing, and you discover that people are not more original in London than they are anywhere else."

The chief thing I noticed about Thomas Hardy, during the Aldeburgh visit, was his modesty. In spite

of Clement Shorter's typical attempts to draw him out and make him play to the gallery, he remained unobtrusively himself, speaking in his gentle refined voice when he had something to say, but never for politeness' sake or for any other conventional reason. It was a delight to watch his face, especially in repose, so wise and so sensitive, already the face of an old man, in which, for all that, shone eyes that could not grow old because they were always on the watch. I have only occasionally seen eyes like his - in Edward Carpenter, for instance and in each case they betokened, I think, that eternal vigilance which allows no cruelty or injustice to pass unchallenged.

Hardy's tendency to relate gruesome and horrible incidents he had experienced or heard of, particularly in connection with the Boer War, then fresh in people's minds, struck me as slightly morbid: it seemed as though we could not avoid the macabre in any conversation to which he contributed. He was particularly concerned over the sufferings of horses in war-time, and declared emphatically that they should never be sent to the Front. That was before the Great War had by comparison reduced the atrocities of the South African campaign almost to unimportance.

I understood better the meaning of Thomas Hardy's obsession by the darker side of life when I met him again, in the summer of 1907, almost literally on his native heath. I was spending the holidays with my sister and her husband, Malcolm McCall, and their little daughter May (afterwards Mrs. Maurice Caillard), at Lulworth Cove; and I cycled over to Dorchester, one day, to lunch with the John Lanes, who were staying at the Antelope. I met Thomas Hardy in the town and spent a memorable hour or so in his company while he took me round his old haunts and told me stories of his boyhood. Among other places, we visited the china shop behind which he had discovered an Elizabethan playhouse; at least, he said it was an Elizabethan play-house, and I was quite ready to take his word for it as we clambered over packing-cases and a litter of straw to explore the raised platform at the back of the shop, which, he explained, was formerly the stage. The scepticism in the matter displayed by the proprietor of the shop was perhaps only local inability to appreciate a theory advanced by a genius who had once played as a boy in the streets of Dorchester. " Oh, aye," he observed indulgently, when I made polite remarks about the distinction of possessing a Shakespearean relic in his backyard, " Mr. Hardy does say something of the kind."

The psychology of that schoolboy who had once haunted the streets of Dorchester was revealed in flashes during our stroll about the town. Thomas Hardy told me he could just remember the public executions there, and added the tale of one revolting atrocity in connection with a woman which made one feel that, in spite of lingering barbarities in our penal system, we have moved slightly forward in our time. The hangings took place, he said, outside the King's Arms, always at ten minutes past twelve in order to allow for the arrival of a possible reprieve by the London coach, which came in at midday.

He also took me down by the river to point out the thatched cottage still known as the hangman's house, where, with other boys, he used to go after dark, to climb on the window-sill and peep through a chink in the blind at the dreaded executioner.

(3) Emma Hardy, letter to Mary Hardy (February 1896)

I dare you, or anyone to spread evil reports of me - such as that I have been unkind to your brother, (which you actually said to my face) or that I have "errors" in my mind (which you have also said to me), and I hear that you repeat to others.

Your brother has been outrageously unkind to me - which is entirely your fault: ever since I have been his wife you have done all you can to make division between us; also, you have set your family against me, though neither you nor they can truly say that I have ever been anything but just, considerate, and kind towards you all, notwithstanding frequent low insults.

As you are in the habit of saying of people whom you dislike that they are "mad" you should, and may well, fear, lest the same be said of you... it is wicked, spiteful and most malicious habit of yours.

You have ever been my causeless enemy - causeless, except that I stand in the way of your evil ambition to be on the same level with your brother by trampling, upon me... doubtless you are elated that you have spoiled my life as you love power of - any kind, but you have spoiled your brother's and your own punishment must inevitably follow - for God's promises are true for ever.

You are a witch-like creature and quite equal to any amount of evil-wishing & speaking - I can imagine you, and your mother and sister on your native heath raising a storm on a Walpurgis (the eve of 1st May when witches convene and hold revels with the devil).

(4) Arthur C. Benson, diary entry (September, 1912)

Mrs Hardy is a small, pretty, rather mincing elderly lady with hair curiously puffed and padded and rather fantastically dressed. It was hard to talk to Mrs Hardy who rambled along in a very inconsequentional way, with a bird-like sort of wit, looking sideways and treating my remarks as amiable interruptions... It gave me a sense of something intolerable the thought of his having to live day and night with the absurd, inconsequent, huffy, rambling old lady. They don't get on together at all. The marriage was thought a misalliance for her, when he was poor and undistinguished, and she continues to resent it.... He is not agreeable to her either, but his patience must be incredibly tried. She is so queer, and yet has to be treated as rational, while she is full, I imagine, of suspicions and jealousies and affronts which must be half insane.

(5) Andrew Norman, Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011)

Why, in view of the trauma that he had suffered, did Hardy not simply walk away from Emma and petition for a divorce? There were several possible reasons: one was pride - in that he wished to avoid a scandal, which may have led to him being ostracised by society and shunned by his publisher; also, lie still felt responsible for Emma's welfare, and he could not bear the thought of the upheaval which this would entail, including the disruption to his writing. The over-riding reason, however, may have been that, as will be seen, the vision of Emma as he had once perceived her - the beautiful woman who had transfixed him, perhaps at first sight - had not left him, and it never would. And he would spend the remainder of his days in bewilderment, searching for his lost Emma, and hoping against hope that the vision would return.