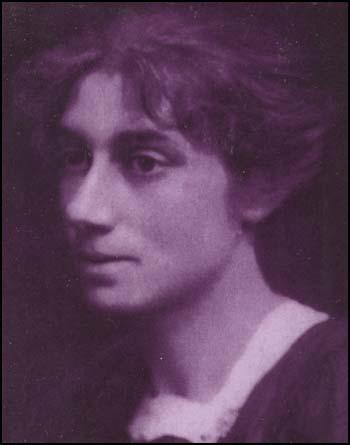

Evelyn Sharp

Evelyn Sharp, the ninth of eleven children, and the youngest of four daughters, was born on 4th August 1869. Her father, James Sharp, was a slate merchant. Her mother, Jane Boyd Sharp, was the youngest daughter of lead merchant from north Wales. (1) Evelyn's brother, Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), later gained fame as the leader of the folk-dance revival. Another brother, Lewin Sharp, became an architect who designed the Apollo Theatre. (2)

As a child Evelyn lacked self-confidence in a large family that favoured the boys. (3) When she was twelve her parents sent her to became a border at Strathallan House School. She enjoyed her time at Strathallan: "the only supremely satisfactory experience of childhood... school was the great adventure of late Victorian girlhood, where girls for the first time found their own level." (4)

Evelyn passed the Cambridge Higher Local Examination in history. Whereas her brothers went to the University of Cambridge, she was sent to a finishing school in Paris. According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "She began to resent being one of a sex that was told to be good rather than clever and was soon advocating women's higher education." (5) This was expressed in an article she wrote for the magazine, Atalanta. She pointed out that reading had "raised my woman's ideal higher and higher, as a being who is neither the rival nor the inferior of man." (6)

Writer in London

Against the wishes of her family, Evelyn Sharp moved to London where she undertook daily tutoring while writing articles for magazines aimed at young girls: "She appeared to possess empathy with the child's perception of the world, depicting ‘grown ups' as the mysterious, irrational ones. Her fairy stories and schoolgirl tales were neither patronizing nor moralistic though they reflect her own increasingly progressive views on gender, class, internationalism, and peace." (7)

Evelyn Sharp later claimed that a writer should approach children as equals and "make them feel on a level with the author". Sharp also wrote and published several novels including, The Making of a Prig (1897), All the Way to Fairyland (1898) and The Other Side of the Sun (1900). She also took a keen interest in politics and helped the Women's Industrial Council to investigate the sweated trades in which women worked for low wages in shocking conditions. (8)

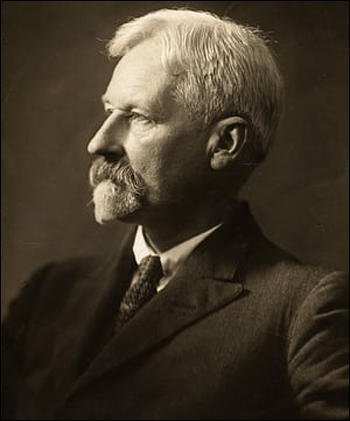

Henry Nevinson

On 30th December 1901, Evelyn Sharp met Henry Nevinson for the first time at the Prince's Ice Rink in Knightsbridge. She later recalled, "when he took my hand in his and we skated off together as if all our life before had been a preparation for that moment." (9)

Nevinson was employed by The Daily Chronicle and was well-known for his war reporting. He was also a Christian Socialist and was a campaigner for many different progressive causes, including women's suffrage. He was married to Margaret Wynne Jones, a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. The couple had one daughter, Philippa Nevinson, a talented musician, and one son, the successful painter Richard Nevinson. (10)

Although he was married they soon became lovers. Nevinson wrote in his diary that he was attracted to her intelligence and was impressed by the way she coped with his intellectual friends, "a gallant thing for a young girl". (11) Evelyn "was both pretty and wise - exquisite in every way she seemed, with eyes singularly brilliant". (12) Evelyn later told him: "The first time I saw you I knew you wanted something you have never got." (13)

The situation was further complicated by the fact that since 1892 Nevinson had having an affair with Nannie Dryhurst. a beautiful Irishwoman who was married to a man who worked for the British Museum. They soon became lovers and according to his biographer: "Nannie became the overriding passion of Henry's life. His interest in Irish nationalism, along with a wider concern about the self-determination of small nations, was fuelled by her... Both partners found out about Henry and Nannie's passionate affair but although evidence suggests that their marriage remained unsatisfactory for all concerned - something it is impossible to judge clearly in retrospect or, indeed, for anybody outside these relationships to fully understand fully - Henry and Margaret did not part." (14)

Evelyn Sharp continued to live alone but continued to have a close relationship with Nevinson, who helped her to find work writing articles for the Daily Chronicle and the Manchester Guardian, a newspaper that published her work for over thirty years. Sharp's journalism made her more aware of the problems of working-class women and she joined the Women's Industrial Council and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Sharp and Nevinson shared the same political beliefs. He told his old friend from university, Philip Webb, that Evelyn possessed "a peculiar humour, unexpected, stringent, keen without poison" but "above all she is a supreme rebel against injustice." (15)

Evelyn Sharp worked as a journalist and a part-time teacher. In November, 1903, her father died: "I went to Brook Green to live for the best part of a year with my mother... By the time I was free again I had lost my teaching connection, and, rather than attempt to work it up again, I determined to rely instead on journalism for my regular income. I was equally sorry to give up my private pupils and my school lecturing, which not only interested me but also brought me into contact with children at a period when I was writing stories about them. At the same time, I have never regretted a change which caused me seriously to adopt a great profession and led to many journeys and adventures that would not otherwise have come my way." (16)

Sharp and Nevinson were both keen walkers and would spent time in the countryside. In 1905 they established the Saturday Walking Club. Other members included William Haselden, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, Clarence Rook and Charles Lewis Hind. According to Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009): "Although Evelyn and Henry were serious walkers, both the Saturday Walking Club and dining with friends afforded the opportunity to be together in public in a manner that was acceptable." (17) When the group went to Ightham Mote Henry wrote that Evelyn was "charming" and "the rest unimportant". (18)

In May 1906 she told Nevinson that she would give up all her literary fame to "belong to you openly and fairly." The following month she wrote to Nevinson: "If it isn't true that you love me it isn't true that the sun shines or that my heart beats quicker when I hear you at the door. My heart is only ill because you put a smile into it that will never die, and my heart had not learnt to smile before." (19)

In another letter she admitted: "All through I have wanted you so terribly to be sure that I should never disappoint you. It is a magnificent thing to be made a Queen by the man who made me a woman. But for you I should never have discovered the meaning of womanhood... I have never done anything to deserve that life should have given me you." (20)

Evelyn Sharp was desperate to have children, but as Nevinson remained married this was impossible. She told a friend that she knew that she was "longing for the impossible" and that "I can hardly bear to look at a baby now." (21) She was now almost thirty-eight and both were well aware that it was more than time that militated against her assuming the responsibilities of motherhood. Even so, she said she would "sooner go on the streets" than marry a man simply because she wanted a child." (22)

Women's Suffrage

In the autumn of 1906 Evelyn Sharp was sent by the Manchester Guardian to cover a speech by Elizabeth Robins. She later wrote: "Elizabeth Robins, then at the height of her fame both as a novelist and as an actress, sent a stir through the audience when she stepped on the platform. The impression she made was profound, even on an audience predisposed to be hostile; and on me it was disastrous. From that moment I was not to know again for twelve years, if indeed ever again, what it meant to cease from mental strife; and I soon came to see with a horrible clarity why I had always hitherto shunned causes." (23)

Sharp, who was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. However, as a result of hearing the speech, Sharp joined the Kensington branch of the Women's Social and Political Union where she met and became friends with Louisa Garrett Anderson and Mary Postlethwaite. The three women sold Votes for Women in Kensington High Street. Sharp later recalled the differences between the suffragists (NUWSS) and the suffragettes (WSPU). Suffragists had waited and worked for so long that they felt they could wait a little longer. Suffragettes who had become "suddenly aware of an imperative need, could not wait another minute." (24)

Evelyn Sharp also joined the Women's Writers Suffrage League. She made her first WSPU speech at Fulham Town Hall in January 1907. In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, Sharp admitted that she was terrified by public speaking and that it caused a "cold feeling at the pit of the stomach". (25) She received a letter from Hugh Brown wrote to her that she upset his preconceived notions of her aggressive, many suffragette, with her "half-girl-half-womanly voice". (26)

Emmeline Pankhurst claimed that Evelyn Sharp was one of the WSPU's best speakers and she agreed to tour the country promoting women's suffrage. Her lover, Henry Nevinson, also rated her highly as a public speaker. He pointed out she displayed "every sort of wit & eloquence & surprise & insight". He was struck by the apparent contradiction between her appearance and words: "A strange humorous pathos too, as when standing there so small and beautiful & exquisitely refined.... she was overcome & admired & believed." (27)

Evelyn Sharp often used examples from history to show the need for equality. She appealed to men to help women to gain the vote. She reminded the audiences that women had been involved in the Chartist movement in the 19th century. Evelyn also maintained that if boys were taught more history in school and knew, for example, about the Norse and Celtic women who had fought with men, they might not be so keen to oppose equal rights. (28)

In 1907 Sharp began a regular column on women's suffrage for the Daily Chronicle. However, in November the editor decided to stop the articles because they "alienated" so many readers. C. P. Scott, her editor at the Manchester Guardian, disapproved of the WSPU's tactics but told Henry Nevinson that Sharp was "the ablest and best brain in the movement". (29)

On 1st July 1908, Edith New and Mary Leigh were sentenced to two months for taking part in a Women's Social and Political Union demonstration. When they were released from Holloway Prison, Ethel Sharp was one of those who welcomed them and joined the team of women in white dresses who drew their carriage from Holloway to Clements Inn. They were greeted by a brass band and accorded a ceremonial welcome breakfast attended by the two main leaders of the WSPU, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. (30)

from Holloway to Queen's Hall on 23rd August 1908.

On 13th October 1908, Evelyn Sharp and other members of the Women's Social and Political Union attempted to enter the House of Commons by force. Twenty-four women and twelve men were arrested including Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Mabel Capper, Clara Codd, Helen Crawfurd, Ada Flatman, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Grace Roe and Ada Wright. Evelyn escaped arrest but the following day Nevinson found her "bruised & bleeding" and worn out with "excitement & rage." (31)

As a journalist Evelyn Sharp was always willing to defend the militant tactics of the WSPU. When the Manchester Guardian described an attack on the car of the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith as "unwomanly" she claimed that it was the government who had forced women to adjust their behaviour: "Denied the right, freely exercised by men, of putting questions at a political meeting, denied the power of petition which we had thought was ours by the Bill of Rights, denied the passage into law, while there was time, opportunity, and a favourable majority in the House, of the measure that would have given us our just liberties, we cannot any longer be expected to remember our manners and forget our wrongs when a Prime Minister, guarded by police walks past us in the street." (32)

Sharp also published Rebel Women (1910), a series of vignettes of suffrage life. Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009), has argued: "It brought together in fourteen revealing vignettes the mundane, yet extraordinary, lives of suffragettes. Evelyn tells tales of the unexpected. we see a working-class mother and lady writer making common cause and a little rebel who seizes the moment to join the boys in her own version of cricket. The stories warn us never to jump to conclusions or judge people by appearance." (33)

Prison and Hunger Strikes

Evelyn's mother was unhappy about her daughter being a member of the Women's Social and Political Union and made her promise not to do anything that would result in her being sent to prison. In a letter on 25th March 1911, her mother absolved her from that promise: "I am writing to exonerate you from the promise you made me - as regards being arrested - although I hope you will never go to prison, still I feel I cannot any longer be so prejudiced and must really leave it to your own better judgment. So brave, so enthusiastic as you have been for so long - I have really been very unhappy about it and feel I have no right to thwart you - much as I should regret feeling that you were undergoing those terrible hardships which so many noble and brave women have and are doing still... I feel sure what a grief it has been that you could not accompany your friends: I cannot write more but you will be happy now, won't you?" (34)

Evelyn now became active in the militant campaign. As she later explained: "My opportunity came with a militant demonstration in Parliament Square on the evening of November 11, provoked by a more than usually cynical postponement of the Women's Bill, which was implied in a Government forecast of manhood suffrage. I was one of the many selected to carry out our new policy of breaking Government office windows, which marked a departure from the attitude of passive resistance that for five years had permitted all the violence to be used against us." (35)

Evelyn Sharp was found guilty of breaking government windows and sentenced to a fine of 10s and 35s damages or fourteen days in goal. She refused to pay the fine and was sent to Holloway Prison. (36) In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, she explained what happened when she arrived in prison: "When the doctor asked me if I minded solitary confinement, I surprised him by saying truly that I objected to it because it was not solitary. You might be left alone for twenty-two out of twenty-four hours, but you could never be sure of being left for five minutes without the door being burst suddenly open to admit some official. Yet this threat of interruption, while it destroyed solitude, which I love, never took me from the horror of the locked door, just as one never lost the irritating sense of being peered at through the observation hole." (37)

On 22nd November 1911, Evelyn Sharp wrote from her prison cell: "Just by sitting here with cold feet and being given suet pudding (without treacle) for dinner, and going without a bath, and being treated like rather a dangerous child - one is doing more for the cause than all the eloquence of the last five years." (38)

On 5th March 1912, detectives arrived at the WSPU headquarters at Clement's Inn to arrest Christabel Pankhurst, Mabel Tuke, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence. It was the Pethick-Lawrences who edited and financed the WSPU's newspaper, Votes for Women. They believed that Evelyn Sharp, who had been a regular contributor, was the one person with the requisite technical experience and political acumen to take over the paper as editor. (39)

Evelyn Sharp agreed to takeover as the salaried editor with the responsibility for the newspaper's production. Volunteers helped prepare the newspaper's layout as well as pack and despatch. Contributors were not paid. Evelyn was keen to get authors and politicians to write for the newspaper. As a well-known writer, she knew many famous people and was in a good position to persuade them to contributor. Elizabeth Robins has argued that the newspaper now had an editor of "distinguished ability and rare devotion." (40)

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (41)

As a result of this expulsion, the Women's Social and Political Union lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, The Suffragette. Evelyn Sharp continued to edit the paper for the Pethick-Lawrences. She told Elizabeth Robins: "I am in a terrible position. All my sympathies are with the Lawrences, but I cannot be sure that I think him (Frederick Pethick-Lawrence) right in his view of militancy." He told Evelyn that acts of militancy "calculated to take human life" were both inexpedient and wrong. The newspaper was to remain "as militant as ever" but "would not incite to violence". (42)

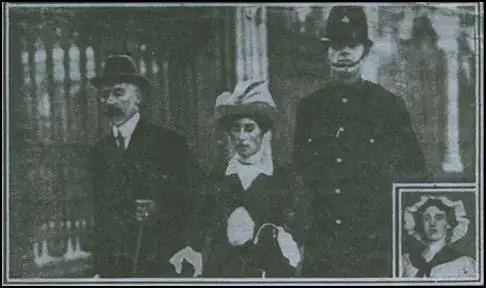

Sharp was also an active member of the Women Writers Suffrage League and on 24th July 1913 she was chosen to represent the organisation in a delegation that hoped to meet with the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, at the House of Commons to discuss the Cat and Mouse Act. McKenna was unwilling to talk to them and when the women refused to leave the building, Mary Macarthur and Margaret McMillan were physically ejected and Evelyn Sharp, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Sybil Smith were arrested. Henry Nevinson saw Evelyn being led off "deadly white with indignation". (43)

The three women were sentenced to fourteen days in prison. They all went on hunger strike. Evelyn's mother wrote: "No one will ever realize, how much I admire your courage in going through all this suffering for acting up to your strong conscience & principles which as you know I fully share." She was worried about Evelyn going on hunger strike and admitted that "every mouth full I eat seems as poison to me." (44)

The arrest of Sybil Smith, the daughter of the William Randal McDonnell, 6th Earl of Antrim, and the mother of seven children, created problems for the government and Sharp and the other suffragettes were released unconditionally after four days. Henry Nevinson arrived at the prison gates with red roses and a bottle of Muscat. He wrote in his diary that they "had perfect happiness again". (45)

Weighing less than seven stone Evelyn Sharp was taken to the home of Hertha Ayrton where she was looked after by her doctor friend, Louisa Garrett Anderson. Detectives and reporters were posted close to the house. A few days later she spent time in the Oxfordshire home of Gerald Gould and Barbara Ayrton Gould in an attempt to recover her health. (46)

On 6th February 1914 Evelyn Sharp joined a group of supporters of women's suffrage, who were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form the United Suffragists movement. Members included Henry Harben, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Neal, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Barbara Ayrton Gould, Gerald Gould, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman. (47)

Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. On 9th February with Henry Nevinson in the chair, the United Suffragists discussed a manifesto. Evelyn became in time the United Suffragists' most energetic member. However, as a result of this work and editing the Votes for Women, she was too busy to continue writing regularly for the Manchester Guardian. (48)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (49)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote an article in The Suffragette where she argued: "A man-made civilisation, hideous and cruel enough in time of peace, is to be destroyed... This great war is nature's vengeance - is God's vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection... that which has made men for generations past sacrifice women and the race to their lusts, is now making them fly at each other's throats and bring ruin upon the world... Women may well stand aghast at the ruin by which the civilisation of the white races in the Eastern Hemisphere is confronted. This then, is the climax that the male system of diplomacy and government has reached." (50)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. (51)

Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (52) In another interview she stated: "We suffragists... do not feel that Great Britain is in any sense decadent. On the contrary, we are tremendously conscious of strength and freshness." (53)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (54)

In October 1915, The WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral." (55)

Evelyn Sharp and the Votes for Women took a very different approach to the war. Some like Beatrice Harraden objected to the unpatriotic tone of some of the paper's articles. Evelyn was also asked by C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, to modify the pacifist tone of some of her stories that were published in the newspaper during the war. Evelyn was anxious to challenge the notion that women had no right to a voice in questions of war and peace because they did not actively participate in war. (56) Laurence Housman, a United Suffragist vice-president, later recalled the "devoted service of Evelyn Sharp", adding that most who remained active in the cause were pacifists "or of pacifist tendency, and were suspect to the rest". (57)

Sharp also campaigned in retaining the separation allowances. Soldiers' and sailors' wives were paid 12s 6d weekly with an extra 2s for each child, many receiving rather more money than their prewar housekeeping allowance had provided. The War Office and Home Office issued a memorandum on stopping allowances to the "Unworthy", requesting that the police check whether recipients were guilty of drunkenness or consorting with men. Sharp chaired a Caxton Hall meeting in which Sylvia Pankhurst and Henry Nevinson protested against the monitoring of separation allowances. (58)

During the First World War a group of wealthy suffragettes, including Janie Allan, decided to fund the Women's Hospital Corps. Evelyn Sharp did support this venture and she visited Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray when they were running the hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. (59)

A pacifist, Sharp was active in the Women's International League for Peace that was established soon after the war started. She was one of 156 British women invited to its conference in The Hague in April 1915. Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, refused permission for the women to go. Only Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, who had already left the country, managed to attend the conference. (60)

Sharp was also a member of the Tax Resistance League and refused to pay income tax on her earnings. She argued that to do so amounted to "taxation without representation". By 1917 she owed six years' tax and the authorities declared her bankrupt. Heating, lighting and telephone were cut off. Her possessions, including her precious typewriter, were seized and sold at public auction. Even her wash-stand had been removed and only her clothes and bed remained. Her friends came to her aid and purchased items that they later gave back to her. (61)

Qualification of Women Act

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. Lilian Lenton, who had played an important role in the militant campaign later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30." (62)

Sylvia Pankhurst was highly critical of the proposed Representation of the People Act. She published a letter in The Call newspaper explaining why: "(i) A woman is not to vote until 30 years of age, though the adult age is 21. (ii) A woman is on a property basis when enfranchised. (iii) A woman loses both her Parliamentary and local government vote if she or her husband accept Poor Law Relief; her husband retaining his Parliamentary and losing his local government vote if he accepts Poor Law Relief. (iv) A woman loses her local government vote if she ceases to live with her husband, ie. if he deserts her, she loses her vote, he retains his. (v) Conscientious Objectors to military service are to be disenfranchised." (63)

The Representation of the People Act was passed in February, 1918. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The Representation of the People Bill, which doubles the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent." (64)

The Act extended the franchise in parliamentary elections, to men aged over 21, whether or not they owned property, and to women aged over 30 who resided in the constituency or occupied land or premises with a rateable value above £5, or whose husbands did. At the same time, it extended the local government franchise to include women aged over 21 on the same terms as men. As a result of the Act, the male electorate was extended by 5.2 million to 12.9 million. The female electorate was 8.5 million. Women now accounted for about 39.64% of the electorate. (65)

Evelyn welcomed the passing of the legislation. She hosted a dinner in honour of suffrage victory. Guests included Henry Nevinson, Elizabeth Robins, J. A. Hobson, Gerald Gould and Barbara Ayrton Gould. A suffrage dinner was held at the Lyceum Club where Evelyn gave a "superb" speech where she displayed "a kind of humorous passion." (66) Evelyn later recalled it was "almost the happiest moment of my life". (67)

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the General Election in December, 1918. Seventeen women candidates that stood in the post-war election. Christabel Pankhurst represented the The Women's Party in Smethwick. The Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down so it would be a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party. Christabel accused the Labour candidate, John E. Davidson, of being a Bolshevik. Davidson replied that far from being "corrupted and led by Bolshevists' the Labour Party stood for social reform along constitutional lines "without breaking a single window, firing a single pillar-box, or burning down a single church." Davidson beat Pankhurst by 775 votes. (68)

Constance Markiewicz served fourteen months of her sentence at Aylesbury Prison before being released in the general amnesty of June 1917. She was immediately elected to the executive of Sinn Fein. Soon afterwards she was imprisoned again for her part in the campaign against the conscription of Irish men into the British Army. After the passing of the passing of the Qualification of Women Act, Constance, while in prison, stood as the Sinn Fein candidate for the St. Patrick's division of Dublin. She was the only woman who was successful in the 1918 General Election. However, like the seventy two Sinn Fein MPs, she did not attend the House of Commons in London. (69)

Henry Nevinson later argued that the persistence of the United Suffragists that had made the triumph of 1918 possible. He added that all its members would admit that our very existence through those four years from February 1914 to February 1918, were almost entirely due to the brilliant mind and dogged resolution of Evelyn Sharp, who inspired our members to maintain their enthusiasm." (70)

Journalism and Relief Work

After the Armistice, Evelyn Sharp, now a member of the Labour Party, worked as a journalist for a variety of newspapers, including the Daily Herald and the Manchester Guardian. She welcomed the Russian Revolution and in November, 1917, she had written in her diary that she was "thrilled at the news of the Russian Revolution". (71)

Evelyn Sharp visited Russia several times. In an article published in The Nation in 1919, Sharp argued that the Bolsheviks were creating a society "in which no one shall starve, and no able-bodied person shall be idle". She added that communism was "the most magnificent ideal of life ever conceived." She equated communism with the basic teachings of Christianity and that it was "bound to come" to Britain. (72)

In July 1919, Joan Mary Fry and Violet Tillard and two other members of the Society of Friends Nursing Unit, went to defeated Germany to see how they could possibly mitigate the disastrous impact of the continued Allied Blockade. Fry wrote: "It is unspeakable what the tiny mites look like; the pain goes down so deep that every now and then it gives a horrid shock to one's faith in love as the key note of the world." (73)

In May 1920 Evelyn Sharp joined Fry and her Quaker volunteers to feed students in starving Germany. She also sent back reports on the situation that was published in The Daily Herald. "She was most struck by the contrast between the children's clean clothes and their shocking thinness." (74) On her return to England she gave talks on German distress to a variety of organisations. By the end of the year the British Quakers were feeding twelve thousand children there. (75)

In January 1921 she went to collect facts, sift evidence and be an eye witness to what was then happening in Ireland. She was appalled by the way the British Army acted during this period: "Worst of all kinds of shame is the shame one feels on being unable honestly to defend one's own country; and I think that, spiritually, the credit of England can scarcely ever have sunk lower than... when the Auxiliaries and Black-and-Tans were let loose upon the population of Ireland." (76)

Sharp was in Russia in January 1922, She met Anatoli Lunacharsky, the People's Commissar for Education. He tried to completely reform Russian education system. He also introduced a system for subsidizing the arts. Another innovation was Workers' Faculties that provided intensive and accelerated courses to train technicians and administrators from the working classes and the peasantry. Lunacharsky was also responsible for the Soviet Government's campaign against adult illiteracy. In 1917 over 65 per cent of the adult population were illiterate. Sharp was very impressed with Lunacharsky and praised his "passion and culture" and commented that the children in Russia looked more "healthy-looking" than "those I left behind at Wapping". (77)

Sharp never joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and after Joseph Stalin took power she become totally disillusioned by the repressive measures of the Soviet government. Sharp had been influenced by the socialist utopian writing of William Morris and loved his book, News from Nowhere (1890). Her friend, Edward Carpenter, also helped shape her political thinking. "He held, and put into practice in his own life, progressive ideas about the transformation of social and gender relations, underpinned by a commitment to spiritual freedom and belief in people enjoying closer harmony with their inner nature and nature itself." (78)

In May 1922 the Manchester Guardian started a daily Women's Page. Edited by Madeline Linford, it dealt with "subjects which are special to women" and aimed at the "intelligent woman". (79) Evelyn Sharp was its first regular columnist. Other contributors included Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby. As Angela V. John has pointed out: "It became renowned, provoking debates about the necessity for space dedicated to women." (80)

Marriage

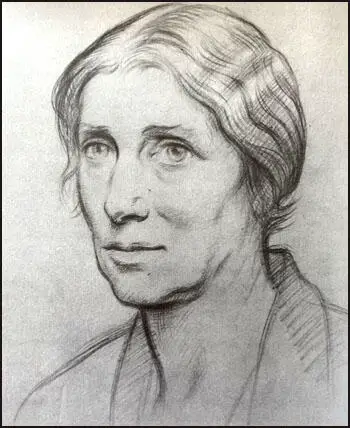

Evelyn Sharp spent a lot of time with Henry Nevinson but he still lived with his wife Margaret Nevinson. They used to eat separately except for Sundays. Their son, Richard Nevinson, described their home "a cheerless uninhabited house". Henry also had a difficult relationship with his daughter, Philippa Nevinson. He wrote "to think what trouble we spent on her and how well she promised". He added "Children are a quiverful of arrows that pierce the parents' hearts." (81)

In 1928 Margaret told friends that she wanted to go into a nursing home "and have done with it". In 1929 she had a non-malignant growth on her colon removed. Margaret became depressed and tried to drown herself in the bath. Suffering from delusions, she believed there was a plot to assassinate her. Richard Nevinson wanted her to be put in a asylum but Henry thought this cruel and so preferred to pay for care at home. (82)

Henry Nevinson wrote to Elizabeth Robins about her health: "At present I am in great tribulation, for Mrs. Nevinson's mind is rapidly failing, and I am perplexed what is best for her. To send her to a mental home among strangers seems to me cruel, but all are urging it, partly in hopes of reducing the great expense. I am so much opposed to it that I should far rather go on spending my small savings in the hope that she may end quietly here." (83)

Margaret Nevinson died of kidney failure at her Hampstead home, 4 Downside Crescent, on 8th June 1932. After her death Henry wrote that he had given her "an unhappy life, but for Richard, adding "and with her I was unhappy too. But it was impossible to part." (84)

Evelyn and Henry became engaged in December, 1932. The Western Mail reported that the engagement "created the liveliest interest in literary circles. (85) In an interview with The Daily Telegraph Henry explained that they had been "comrades and colleagues in a great many causes". Evelyn added that Henry had always been on the side of militant women in the struggle for women's suffrage. (86)

Evelyn was 63 and Henry was in his seventy-seventh year. Evelyn wrote that "I intend to start out on the greatest, because it is the commonest, of all adventures. It is also the most uncertain: that is why it seems unreasonable to leave it, as it is generally left, to the young adventurer. If age and experience have any value at all, they should help and not hinder the explorer who sets out to sail the uncharted seas of married life." (87)

stands behind him and Richard Nevinson is on the right of the photograph.

The prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, wrote to them offering to be best man but they refused as he had lost his commitment to socialism and they had not approved of him becoming the leader of the National Government. The couple married on 18th January 1933 at Hampstead Registry Office. Evelyn shocked the guests by wearing a black dress for the ceremony. (88)

Evelyn Sharp became very concerned when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party took power in 1933. The following year the French feminist Gabrielle Duchêne became chairman of the World Committee of Women against War and Fascism. Sharp joined the organization. Other members included Charlotte Despard, Sylvia Pankhurst, Ellen Wilkinson, Vera Brittain, Margaret Storm Jameson and Melita Norwood. (89)

Second World War

Living in London during the Second World War was very dangerous after the start of the Blitz. In a twenty-four-hour period three large bombs fell very near their home at 4 Downside Crescent. On 13th October, 1940, a 250-pound bomb struck their roof. Nearly all the windows at the back of the house were blown out. Ten minutes later another bomb brought down three houses close-by. Henry wrote: "I have seldom touched such depths of misery and age quenches hope." (90)

The couple moved to the beautiful village of Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire. The historian George Macaulay Trevelyan, described its High Street as "The most beautiful street now left in the island". (91) The Nevinsons had several friends living in the village and they also attended "Cotswold Winter Evenings" and the debating society at the Town Hall. (92)

Henry Nevinson suffered from diabetes and his mobility declined. He lost weight and fell several times. Evelyn told a friend he was "profoundly homesick and miserable". He died aged 85 on 9th November, 1941. Sharp wrote in her diary that he stopped breathing but "his face did not change, or become less beautiful". She added: "There was a flaming red sunset right across the sky and the reflection of it was across the room." (93)

Margaret Storm Jameson commented: "Are there left men such as Henry Nevinson was? Passionate quixote's who feel injustice anywhere in the world as a nail driven into their own flesh." (94) Jameson told Evelyn that "you were woven into his life by memories, going back years and years" and that he had depended on her "as an anchor and centre". Maude Royden claimed that Evelyn and Henry's "happiness had lit up a room like a lamp". George Peabody Gooch added that the "greatest thing in his life was their love for each other". (95)

Evelyn Sharp moved back to London and lived in a flat, 23 Young Street, Kensington. Over the next few months she occupied herself by sorting out his affairs and seeing through the publication of his anthology, Words and Deeds (1942). At times she was overwhelmed with loneliness that she confessed to being "nearly beaten". (96) However, in a letter to the Society of Authors she remarked: "When the world is behaving so horribly what does it matter if one person has stopped being happy." (97)

Evelyn was strongly against the bombing of civilians. She wrote: "I cannot bear to think of what we have done to Berlin, not because I love Berlin but because I love England more." (98) Evelyn added that German atrocities could not be criticised considering what the Allies were doing. (99)

Last Years

Henry Nevinson's house, 4 Downside Crescent, was left to Evelyn, Philippa and Richard. It had cost £1,225 when it was bought in 1901, but because of bomb damage it was sold for £650. However, Evelyn did not struggle financially and had a reasonable income. She wrote in her diary, "I have dreaded being a widow who is left comfortably off." (100)

Evelyn remained in contact with several of her old friends involved in the struggle for women's suffrage. In the summer of 1947 she visited Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. However, in October she was not well enough to attend Emmeline's eightieth birthday party. By January 1948 she was in a nursing-home at 32, Woodville Gardens, Ealing. The following year she moved to the nearby Methuen Nursing Home, 13 Gunnersbury Avenue. (101)

Evelyn Sharp died aged eighty-five in the Methuen Nursing Home on 17th June 1955. The Manchester Guardian noted in her obituary that her death "breaks one of the few remaining links between those who fought for women's emancipation and those who now possess it." It added that her recent life had been "clouded and circumscribed by the failure of her sight." (102)

During her life she had published over thirty books including fifteen novels, twelve collections of short stories, four non-fiction works, seven pamphlets, the libretto for an opera by Ralph Vaughan Williams, a history of folk dancing and a life of the physicist Hertha Ayrton. (103)

Primary Sources

(1) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

At first, all I saw in the enfranchisement of women was a possible solution of much that subconsciously worried me from the time when, as a London child, I had seen ragged and barefoot children begging in the streets, while I with brothers and nurses went by on the way to play in Kensington Gardens. Later, there were agricultural labourers with their families, ill-fed, ill-housed, ill-educated, in the villages round my country home, and after that, the sweated workers.

I made spasmodic excursions into philanthropy, worked in girls' clubs and at children's play hours, joined the Anti-Sweating League, helped the Women's Industrial Council in one of its investigations. When the early sensational tactics of the militants focussed my attention upon the political futility of the voteless reformer, I joined the nearest suffrage society, which happened ironically to be the non-militant London Society.

(2) Angela V. John, Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009)

Henry Nevinson was judged by men and women to be exceedingly good-looking. He offered an unusual combination of military bearing and adventurous international lifestyle with a knack for sensitively appreciating women's perspectives. A sensual man, he was especially popular with progressive women and was easily flattered. He spent much of his life travelling and acted as though he was not married. Apart from a sustained flirtation with Jane Brailsford (married to his colleague Noel Brailsford), and one or two other intense female "friendships", it was Nannie and Evelyn who monopolised his emotions.

(3) Evelyn Sharp, letter to Henry Nevinson (5th June, 1906)

If it isn't true that you love me it isn't true that the sun shines or that my heart beats quicker when I hear you at the door. My heart is only ill because you put a smile into it that will never die, and my heart had not learnt to smile before.

(4) Evelyn Sharp, letter to Henry Nevinson (8th March, 1907)

All through I have wanted you so terribly to be sure that I should never disappoint you. It is magnificent thing to be made Queen by the man who made me a woman. But for you I should never have discovered the meaning of womanhood... I have never done anything to deserve that life should have given me you.

(5) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

There was very little leisure in which to analyse one's motives in that astonishing rush of years: it is only in retrospect that I see how inevitable was the choice I made in the autumn of 1906, when I first came in contact with the fiery spirits of the Women's Social and Political Union and had to decide whether to throw in my lot with them or to turn my back on the whole disturbing question. There were, I think, two lines of approach to that question. Either you saw the vote as a political influence, or you saw it as a symbol of freedom. The desire to reform the world would not alone have been sufficient to turn law-abiding and intelligent women of all ages and all classes into ardent rebels. Reforms can always wait a little longer, but freedom, directly you discover you haven't got it, will not wait another minute; and the crude difference, as I see it now, between the women who belonged to the non-militant societies, or to none at all, and the women whose militancy sent repeated shocks through the world between 1905 and 1914, was the difference between those who, having waited and worked so long (and without their magnificent preparatory work militancy would have been an anomaly), could wait a little longer, and those who, suddenly aware of an imperative need, could not wait another minute.

(6) Jane Sharp, letter to Evelyn Sharp (25th March, 1911)

I am writing to exonerate you from the promise you made me - as regards being arrested - although I hope you will never go to prison, still I feel I cannot any longer be so prejudiced and must really leave it to your own better judgment. So brave, so enthusiastic as you have been for so long - I have really been very unhappy about it and feel I have no right to thwart you - much as I should regret feeling that you were undergoing those terrible hardships which so many noble and brave women have and are doing still... I feel sure what a grief it has been that you could not accompany your friends: I cannot write more but you will be happy now, won't you?

(7) Evelyn Sharp was converted to the need for militant action by a speech made by Elizabeth Robins at Tunbridge Wells in the autumn of 1906.

Elizabeth Robins, then at the height of her fame both as a novelist and as an actress, sent a stir through the audience when she stepped on the platform. The impression she made was profound, even on an audience predisposed to be hostile; and on me it was disastrous. From that moment I was not to know again for twelve years, if indeed ever again, what it meant to cease from mental strife; and I soon came to see with a horrible clarity why I had always hitherto shunned causes.

(8) Evelyn Sharp believed that the role played by the Men's League for Women's Suffrage was very important in the struggle for the vote.

It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Landsbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war.

(9) Jane Sharp, letter to her daughter, Evelyn Sharp (November, 1911)

Although I hope you will never go to prison, still, I feel I cannot any longer be so prejudiced, and must leave it to your better judgment. I have really been very unhappy about it and feel I have no right to thwart you, much as I should regret feeling that you were undergoing those terrible hardships. It has caused you as much pain as it has me, and I feel I can no longer think of my own feelings. I cannot write more, but you will be happy now, won't you.

(10) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

My opportunity came with a militant demonstration in Parliament Square on the evening of November 11, provoked by a more than usually cynical postponement of the Women's Bill, which was implied in a Government forecast of manhood suffrage. I was one of the many selected to carry out our new policy of breaking Government office windows, which marked a departure from the attitude of passive resistance that for five years had permitted all the violence to be used against us.

(11) In November 1911 Evelyn Sharp was sentenced to fourteen days in Holloway Prison.

When the doctor asked me if I minded solitary confinement, I surprised him by saying truly that I objected to it because it was not solitary. You might be left alone for twenty-two out of twenty-four hours, but you could never be sure of being left for five minutes without the door being burst suddenly open to admit some official. Yet this threat of interruption, while it destroyed solitude, which I love, never took me from the horror of the locked door, just as one never lost the irritating sense of being peered at through the observation hole.

(12) Angela V. John, Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009)

Evelyn Sharp became in time the United Suffragists' most energetic member... There was something of a rift with Louisa Garrett Anderson who had been very supportive and helpful when Evelyn was imprisoned... Louisa had written passionate letters to Evelyn... Henry Nevinson's diary suggests that it was Louisa's close friendship with Dr. Flora Murray (with whom she had founded the Woman's Hospital for Children) that Evelyn could not tolerate. He even refers to Dr. Murray's "bullying absorption" of Louisa.

(13) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

When militants and non-militants alike hastened to offer war service to the Government, no doubt many of them felt, if they thought about it at all, that this was the best way of helping their own cause. Certainly, by their four years' war work, they did prove the fallacy of the anti-suffragist' favourite argument, that women had no right to a voice in questions of peace and war because they took no part in it.

Personally, holding as I do the enfranchisement of women involved greater issues than could be involved in any war, even supposing that the objects of the Great War were those alleged, I cannot help regretting that any justification was given for the popular error which still sometimes ascribes the victory of the suffrage cause, in 1918, to women's war service. This assumption is true only in so far as gratitude to women offered an excuse to the anti-suffragists in the Cabinet and elsewhere to climb down with some dignity from a position that had become untenable before the war. I sometimes think that the art of politics consists in the provision of ladders to enable politicians to climb down from untenable positions.

(14) C. P. Scott, letter to Evelyn Sharp (28th July, 1915)

The war is making every domestic question wear a new face and is going to revolutionise our politics. We shall have a hard fight to see that the change takes effect in the right direction. It certainly ought to, as regards the recognition of women's capacity and work and their whole position in the State. One's hope is in the possibility of a changed point of view. Whatever the result of the war, we can be safe only by being strong, and where is there a greater reservoir of strength than in the ranks of the women ? You can't develop that except by a frank recognition of equality, of which the vote is, with us, the symbol. I'm glad you've stuck to franchise work-I wish others had followed your example.

(15) Angela V. John, The Life and Times of Henry Nevinson (2006)

Returning home from Cambridge on 4th June 1932, he (Henry Nevinson) found Margaret unconscious. She died four days later from kidney failure."' After her death Henry wrote that he had given her "an unhappy life, but for Richard", adding "and with her I was unhappy too. But it was impossible to part." He conceded his early "wrong to Margaret under my passionate love for my dear lady (Nannie)". Less than a fortnight after Margaret's death Henry discussed the future with Evelyn. When Evelyn had gone to Switzerland on holiday in 1926, Henry had written that "It was like parting with life, so close are we."

On 18 January 1933 at Hampstead Register Office, Evelyn aged sixty-three married Henry, now in his seveny-seventh year. It was almost half a century since his first marriage. MacDonald, fond of both of them, offered to be best man. They were flattered but declined. It would have caused difficulties with some guests (he headed a national government and had been expelled from the Labour Party) and would have turned a private occasion into a public event. They invited just a handful of friends. They had booked the previous day but then Henry was asked to speak at a protest meeting against the imprisonment of the union leader Tom Mann. So the veteran radicals postponed events by one day. This was not a conventional wedding and they were nor a conventional couple: the bride wore black.

(16) The New York Times (22nd June, 1955)

Miss Evelyn Sharp, veteran British suffragist and novelist is dead, it was announced here today. Her age was 85. She was put in prison twice for her militant efforts to win the vote for women.

Miss Sharp, a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, had contributed many articles to The Manchester Guardian, The Christian Science Monitor, The New Statesman and other newspapers and periodicals.

Her active work as a speaker and demonstrator for the women's suffrage movement covered the period from 1905 to 1918 after which she devoted herself to international humanitarian causes. She did relief work with the Quakers in Germany in 1920 and the Soviet Union in 1923.

Her novels included, The Making of a Schoolgirl, The Hill That Fell Down, and The Victories of Olivia.

(17) June Purvis, Times Higher Education Supplement (21st May, 2009)

She was a journalist and children's writer who published more than 30 books, many volumes of short stories, a life of the physicist Hertha Ayrton, the libretto for a comic opera by Ralph Vaughan Williams, as well as her own autobiography, but Evelyn Sharp has largely been hidden in history. Her name pops up occasionally, especially in publications on the British suffrage movement, but then it disappears again. Yet, as Angela V. John reveals in this fascinating biography - the first written about this remarkable feminist - there is a story of public achievement to be told as well as the anguished happiness of her long, secret love affair with Henry Nevinson, the radical war correspondent whom she eventually married.

Born in 1869 to privileged parents, Sharp lacked self-confidence in a large family of 11 children that favoured the boys. Her refuge came in reading, storytelling, studying and then writing; the first of her short stories were published in 1893 in a popular magazine. This early success profoundly influenced Sharp's future direction, and she became determined to be a writer. The following year, greatly against her family's wishes, she left home to live on her own in London. Her first novel appeared in 1895, and she also contributed to the infamous literary quarterly The Yellow Book, as well as to respected newspapers. With the help of a small family annuity, supplemented by income from her writing, the self-effacing Sharp gained success as a journalist and as the author of schoolgirl fiction and fairytales.

It was on 30 December 1901, while ice skating in Knightsbridge, that she collided with the handsome and confident Nevinson. Many years later, she recollected how he "took my hand in his and we skated off together as if all our life before had been a preparation for that moment". She was well aware that the charming Nevinson was married to Margaret, a devout Anglo-Catholic, and that they had two children. But Sharp was smitten. However, she did not know that Nevinson, who deeply resented his marriage and lived the life of a bachelor, already had a lover, Nannie Dryhurst, a politicised Irishwoman living close to his home in Hampstead. When Margaret found out about her husband's affair with Nannie, she and Nevinson decided not to part but to lead a semi-detached existence, remaining nominally married for 48 years.

Although Nevinson's affair with Nannie ended in 1912, Sharp's relationship with him spanned more than 30 years before she was able to marry him. Friends came to "appreciate" the situation, but Sharp hated the secrecy of it, especially as, given the circumstances, it would have been inappropriate for her to have a child. The situation was especially hard to bear because she was regarded as an authority on children. Nevinson, for his part, juggled his various relationships, even writing to all three women in his life when he was abroad on various assignments.

The suffragist movement, in which both Sharp and Nevinson became involved, brought them closer together. Sharp joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, and became a leading figure in the local branch in Kensington. An accomplished speaker, she was a founding member and vice-president of the Women Writers' Suffrage League. She went to prison twice but, unlike other suffragettes, was never force-fed. When the WSPU's leaders were arrested in 1912 and Emmeline's daughter Christabel fled to Paris, Sharp took over the editorship of Votes for Women, the WSPU newspaper. Nevinson worked behind the scenes - and greeted his lover with red roses and a bottle of muscat when she was released from Holloway.

Both became disillusioned with the more violent tactics of the WSPU and were instrumental in forming, in early 1914, the United Suffragists, a mixed-sex society that shied away from extremism but vowed not to criticise those who supported it. Nevinson, hardly an impartial observer, overstated the case when he claimed that it was the work of the United Suffragists during the First World War, and "the brilliant mind and dogged resolution of Evelyn Sharp", that made possible in 1918 the enfranchisement of some categories of women over the age of 30. Similarly contentious is John's claim that Sharp was a key figure "holding the suffragettes together once Christabel went abroad". Many key figures in the suffragette movement considered Sharp an intellectual whose close relationship with Nevinson made her suspect.

Student Activities