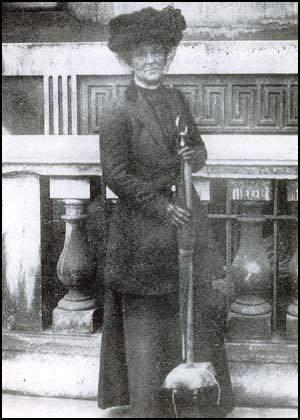

Marion Wallace-Dunlop

Marion Wallace-Dunlop, the daughter of Robert Henry Wallace-Dunlop, of the Bengal civil service, was born at Leys Castle, Inverness, on 22nd December 1864. She later claimed that she was a direct descendant of the mother of William Wallace.

Marion Wallace-Dunlop studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and in 1899 illustrated in art nouveau style two books, Fairies, Elves, and Flower Babies and The Magic Fruit Garden. She also exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1903, 1905 and 1906.

The art critic, Joseph Lennon, has argued: "Wallace-Dunlop’s art and writings, along with her prints, sketches, letters and photos, provide a more complete genealogy of the hunger strike, and show a woman challenging the aesthetic and gender boundaries of her day. Her oil portrait of her sister Constance (Miss C. W. D., 1892) portrays a woman with a shawl wrapped around her shoulders, who sits erect, alarmed, with a tinge of fear, and stares disturbingly out at the viewer. Meeting and challenging our own gaze, her haunted stare makes us feel we have stumbled into a private space, the subject’s own. Wallace-Dunlop had a talent for creating such unsettling images."

Wallace-Dunlop was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1900 she joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. She was also a socialist and was an active member of the Fabian Women's Group. By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. Emily Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), advocated a new strategy to obtain the publicity that she thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. As her biographer, Leah Leneman, points out, "militancy made an immediate appeal to her."

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. The following month Wallace-Dunlop was arrested and charged with "obstruction" and was briefly imprisoned.

Her release was reported in Votes for Women. "On Friday morning the first batch of prisoners to be released from Holloway were met at the prison gates, and escorted in triumph, banners flying and bands playing, to Queen's Hall, where some 250 friends and supporters were waiting to give then a warm welcome.... Miss Dunlop said she hardly dared to tell those present about the infirmary, where she had spent the most terrible days of her life. She could never forget two young girls, one not only young, but bright and pretty - the one condemned to be hanged, the other under trial for child murder." Dunlop was quoted as saying: "I confess I broke down. It was so terrible to feel powerless to help. It made one firmly anxious to come out and help this cause."

While in prison she came into contact with two women who had been found guilty of killing children. She wrote in her diary: "It made me feel frantic to realize how terrible is a social system where life is so hard for the girls that they have to sell themselves or starve. Then when they become mothers the child is not only a terrible added burden, but their very motherhood bids them to kill it and save it from a life of starvation, neglect. I begin to feel I must be dreaming that this prison life can’t be real. That it is impossible that it is true and I am in the midst of it. I know now the meaning of the screened galley in the Chapel, the poor condemned girl sits there with a wardress."

On her release she made a speech about the plight of the working-class: "In this country every year 120,000 babies die before they are a year old, and most of these die because of the conditions into which they are born. It is not so much the babies who die that one pities but those who survive, poor, maimed, starved, stunted little beings."

On 25th June 1909 Wallace-Dunlop was charged "with wilfully damaging the stone work of St. Stephen's Hall, House of Commons, by stamping it with an indelible rubber stamp, doing damage to the value of 10s." According to a report in The Times Wallace-Dunlop printed a notice that read: "Women's Deputation. June 29. Bill of Rights. It is the right of the subjects to petition the King, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitionings are illegal."

Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

In her book, Unshackled (1959) Christabel Pankhurst claimed: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded."

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence wrote to Wallace-Dunlop: "Nothing has moved me so much - stirred me to the depths of my being - as your heroic action. The power of the human spirit is to me the most sublime thing in life - that compared with which all ordinary things sink into insignificance." He also congratulated her for "finding a new way of insisting upon the proper status of political prisoners, and of the resourcefulness and energy in the face of difficulties that marked the true Suffragette."

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), has pointed out: "As with all the weapons employed by the WSPU, its first use sprang directly from the decision of a sole protagonist; there was never any suggestion that the hunger strike was used on this first occasion by direction from Clement's Inn."

Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike. In one eighteen month period, Emily Pankhurst, who was now in her fifties, endured ten of these hunger-strikes.

Wallace-Dunlop visited Eagle House near Batheaston in June 1910 with Margaret Haig Thomas. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Tsuga Mertensiana, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. Mary's mother, Emily Blathwayt, commented in her diary: "Miss Wallace Dunlop and Miss Haig (like so many of them) never eat meat and not much animal food at all... We liked her very much, she was so ladylike."

Wallace-Dunlop joined forces with Edith Downing to organise a series of spectacular WSPU processions. The most impressive of these was the Woman's Coronation Procession on 17th June 1911. Flora Drummond led off on horseback with Charlotte Marsh as colour-bearer on foot behind her. She was followed by Marjorie Annan Bryce in armour as Joan of Arc.

The art historian, Lisa Tickner, described the event in her book The Spectacle of Women (1987): "The whole procession gathered itself up and swung along Northumberland Avenue to the strains of Ethel Smyth's March of the Women... The mobilisation of 700 prisoners (or their proxies) dressed in white, with pennons fluttering from their glittering lances, was, as the Daily Mail observed, "a stroke of genius". As The Daily News reported: "Those who dominate the movement have a sense of the dramatic. They know that whereas the sight of one woman struggling with policemen is either comic or miserably pathetic, the imprisonment of dozens is a splendid advertisement."

Wallace-Dunlop ceased to be active in the WSPU after 1911. During the First World War she was visited by Mary Sheepshanks at her home at Peaslake, Surrey. Sheepshanks later commented: "We found her in a delicious cottage with a little chicken and goat farm, an adopted baby of 18 months, and a perfectly lovely young girl who did some bare foot dancing for us in the barn; we finished up with home made honey."

In 1928 Wallace-Dunlop was a pallbearer at the funeral of Emmeline Pankhurst. Over the next few years she took care of Mrs Pankhurst's adopted daughter, Mary. Joseph Lennon has pointed out: "Wallace-Dunlop never married, but there is no evidence of any sexual relationships with either men or women, despite her many close friendships with the latter."

Marion Wallace-Dunlop died on 12th September 1942 at the Mount Alvernia Nursing Home, Guildford.

Primary Sources

(1) Marion Wallace-Dunlop, diary entry (July, 1908)

Miss Clarkson has been more or less ill all the time, and her nerves have been tortured by hearing that a young girl who used to clean her cell for her has been condemned to be hung for child murder. She also pointed out to me another girl who was exercising, a pretty delicate - looking creature who is on remand and about to be tried for the same offence. It made me feel frantic to realize how terrible is a social system where life is so hard for the girls that they have to sell themselves or starve. Then when they become mothers the child is not only a terrible added burden, but their very motherhood bids them to kill it and save it from a life of starvation, neglect. I begin to feel I must be dreaming that this prison life can’t be real. That it is impossible that it is true and I am in the midst of it. I know now the meaning of the screened galley in the Chapel, the poor condemned girl sits there with a wardress.

(2) Votes for Women (6th August 1908)

On Friday morning the first batch of prisoners to be released from Holloway were met at the prison gates, and escorted in triumph, banners flying and bands playing, to Queen's Hall, where some 250 friends and supporters were waiting to give then a warm welcome….

Miss Dunlop said she hardly dared to tell those present about the infirmary, where she had spent the most terrible days of her life. She could never forget two young girls, one not only young, but bright and pretty - the one condemned to be hanged, the other under trial for child murder. "I confess," said Miss Dunlop, "I broke down. It was so terrible to feel powerless to help. It made one firmly anxious to come out and help this cause."

(3) Marion Wallace-Dunlop, speech (August 1908)

In this country every year 120,000 babies die before they are a year old, and most of these die because of the conditions into which they are born. It is not so much the babies who die that one pities but those who survive, poor, maimed, starved, stunted little beings.

(4) Marion Wallace-Dunlop, petition to the Governor of Holloway Prison (5th July, 1909)

I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.

(5) Christabel Pankhurst, Unshackled (1959)

Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded. Mr. Gladstone did not reply, but after she had fasted ninety-one hours, Miss Wallace Dunlop was set free. She was in an exhausted state, having refused every threat and appeal to induce her to break her fast.

(6) Annie Kenney, Memories of a Militant (1924)

In 1909 Wallace Dunlop went to prison and defied the long sentences that were being given by adopting the hunger-strike. "Release or Death" was her motto. From that day, July 5th, 1909, the hunger-strike was the greatest weapon we possessed against the Government… before long all Suffragette prisoners were on hunger-strike, so the threat to pass long sentences on us had failed. Sentences grew shorter.

(7) Joseph Lennon, Times Literary Supplement (22nd July, 2009)

The doctor, finding her ill on arrival, put her in the infirmary. On the morning of July 5, she amended a petition to the Governor of Holloway to announce her hunger strike. “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.” In referring to those “who may come after me”, she drew attention to the 108 suffragettes arrested on June 29 (at the demonstration she had advertised). Fourteen women arrested for window-smashing were sent to Holloway later that week...

When the doctors realized she would not come off her strike and her health worsened, the Prison Commission instructed the Governor to “release her at once”. The news of her hunger strike and release spread fast around London and the world. The fourteen window-smashers first heard as they were being led from court into a Black Maria. En route they resolved to try the hunger strike themselves, this time in successive waves in order to prolong its newsworthiness. Within a few weeks, and after dozens of newspaper stories, they too were all released, and the suffrage campaign had discovered that, in the words of Annie Kenney, “the hunger-strike was the greatest weapon we possessed against the Government”.

(8) Governor James Scott, letter to Dr Donkin of the Prison Commission (July, 1909)

As you say, she holds very exaggerated views as to the results of the militant tactics in influencing public opinion. She told me, with great glee, on the evening of her reception here, that the sale of their paper had gone up many thousands since the last scene at Westminster. Her idea that if she were to die in Prison, it would help their cause greatly, is probably genuine.

(9) Marion Wallace-Dunlop, speech (1909)

Women have grown to realize their responsibility not only as individuals but also as members of a great community... they have in fact at last recognized that they are part and parcel of what we may call the public conscience.