Women's Social & Political Union (Suffragettes)

On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain (the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the Fabian Society, met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass the motion proposed by Keir Hardie to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). (1)

Emmeline Pankhurst hoped the new Labour Party would support votes for women on the same terms as men. Although the party made it clear in its programme it favoured equal rights for men and women. Hardie argued for "the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men". However, others in the party, including Isabella Ford, thought that as large number of working-class males did not have the vote, they should be demanding "full adult suffrage". Philip Snowden pointed out that if only middle-class women got the vote it would favour the Conservative Party. This was also the view of left-wing members of the Liberal Party such as David Lloyd George. (2)

In the 1902 Labour Party conference Emmeline Pankhurst created controversy when she proposed that "in order to improve the economic and social condition of women, it is necessary to take immediate steps to secure the granting of the suffrage to women on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men". This was not accepted and instead a resolution calling for "adult suffrage" became party policy.

Pankhurst's views on limited suffrage received a great deal of criticism. One of its leaders, John Bruce Glasier, had been a long-term supporter of universal suffrage, and like his wife, Katharine Glasier, was particularly opposed to Pankhurst's views. He recorded in his diary that he disapproved of her "individualist sexism". At a meeting with Emmeline and her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, he claimed that the two women "were not seeking democratic freedom, but self-importance". (3) Trade union leader, Henry Snell, agreed: "Mrs. Pankhurst was magnetic, courageous, audacious, and resolute. Mrs. Pankhurst was an autocrat masquerading as a democrat". (4)

Women's Social and Political Union

After her defeat at conference, Emmeline Pankhurst decided to leave the Labour Party and in October 1903 decided to establish the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Emmeline stated that the main aim of the organisation was to recruit working class women into the struggle for the vote. "We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from any party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. Deeds, not words, was to be our permanent motto." (5)

Some early members included Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Elizabeth Robins, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, May Billinghurst, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Mary Allen, Winifred Batho, Mary Leigh, Mary Richardson, Ethel Smyth, Teresa Billington-Greig, Helen Crawfurd, Eileen Casey, Emily Davison, Charlotte Despard, Mary Clarke, Margaret Haig Thomas, Cicely Hamilton, Florence Tunks, Hilda Burkitt, Clara Giveen, Eveline Haverfield, Edith How-Martyn, Constance Lytton, Kitty Marion, Helen Craggs, Ada Wright, Dora Marsden, Hannah Mitchell, Margaret Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp, Nellie Martel, Helen Fraser, Jennie Baines, Emma Sproson, Minnie Baldock and Octavia Wilberforce.

The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic suggested, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.” As an early member of the WSPU, Dora Montefiore, pointed out: "The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon... the NUWSS." (6)

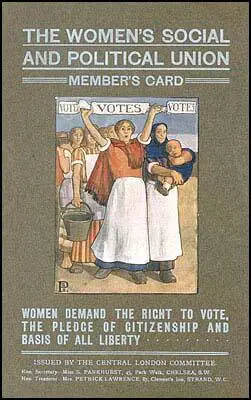

Sylvia Pankhurst studied at Manchester Art School. Although a committed artist, she began spending more and more time working for women's suffrage. When the Women Social & Political Union was formed, Sylvia employed her artistic skills for the organisation. This included designing the Membership Card for the WSPU. It portrayed "in clear, bright colours, the working women, in aprons, clogs, and shawls, whose lives she hoped the campaign would improve." (6a)

The forming of the WSPU upset both the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the Labour Party, the only party at the time that supported universal suffrage. They pointed out that in 1903 only a third of men had the vote in parliamentary elections. On the 16th December 1904, The Clarion published a letter from Ada Nield Chew, a leading figure in the Independent Labour Party, attacking WSPU policy: "The entire class of wealthy women would be enfranchised, that the great body of working women, married or single, would be voteless still, and that to give wealthy women a vote would mean that they, voting naturally in their own interests, would help to swamp the vote of the enlightened working man, who is trying to get Labour men into Parliament." (7)

The following month Christabel Pankhurst replied to the points that Ada Nield Chew made: "Some of us are not at all so confident as is Mrs Chew of the average middle class man's anxiety to confer votes upon his female relatives." A week later Ada Nield Chew retorted that she still rejected the policies in favour of "the abolition of all existing anomalies... which would enable a man or woman to vote simply because they are man or woman, not because they are more fortunate financially than their fellow men and women". (8)

As the authors of One Hand Tied Behind Us (1978) pointed out: "The fiery exchange ran on through the spring and into March. The two women both relished confrontation, and neither was prepared to concede an inch. They had no sympathy for the other's views, and shared no common experiences that might help to bridge the chasm... Christabel, daughter of a barrister... had little personal experience of working women's lives. Ada Nield Chew had known little else... her life had been a series of battles against women's low wages and appalling working conditions." (9)

The WSPU was often accused of being an organisation that existed to serve the middle and upper classes. As Annie Kenney was one of the organizations few working class members, when the WSPU decided to open a branch in the East End of London, she was asked to leave the mill and become a full-time worker for the organisation. Annie joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London and they gradually began to persuade working-class women to join the WSPU. (10)

Nellie Martel, Emmeline Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard.

Teresa Billington Greig found Emmeline Pankhurst a difficult colleague: "To work alongside of her day by day was to run the risk of losing yourself. She was ruthless in using the followers she gathered around her, as she was ruthless to herself. She took advantage of both their strengths and their weaknesses suffered with you and for you while she believed she was shaping you and used every device of suppression when the revolt against the shaping came. She was a most astute statesman, a skilled politician, a self-dedicated reshaper of the world - and a dictator without mercy". (11)

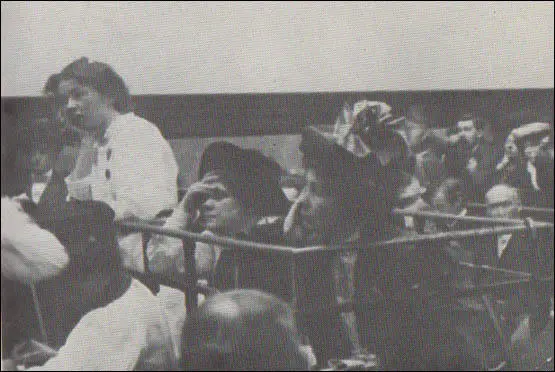

Emmeline Pankhurst was an impressive orator: "The crowd came - packing the hall to overflowing. The rowdy youths came. And one other factor I had scarcely fully reckoned upon came - Mrs. Pankhurst. She held that audience in the hollow of her hand. When a youth interrupted she turned and dealt with him, silenced him, and, without faltering in the thread of her speech, used him as an illustration of an argument. The audience was so intent to hear every word that even when one little group of youths let out that aforementioned evil-smelling gas it did no more than cause a faint stir in one small corner of the hall. As Mrs. Pankhurst continued the interruptions got fewer and fewer, and at last ceased altogether. Even when at the end came question-time, members of the audience were uncommonly chary of delivering themselves into her hands. That meeting was a revelation of the power of a great speaker." (12)

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. It seemed certain that the Liberal Party would form the next government. Therefore, the WSPU decided to target leading figures in the party. (13)

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were both arrested. (14)

Christabel Pankhurst was charged with assaulting the police and Annie Kenney with obstruction. They were both found guilty. Pankhurst was fined ten shillings or a jail sentence of one week. Kenney was fined five shillings, with an alternative of three days in prison. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. (15)

Emmeline Pankhurst was very pleased with the publicity achieved by the two women. "The comments of the press were almost unanimously bitter. Ignoring the perfectly well-established fact that men in every political meeting ask questions and demand answers of the speakers, the newspapers treated the action of the two girls as something quite unprecedented and outrageous... Newspapers which had heretofore ignored the whole subject now hinted that while they had formerly been in favour of women's suffrage, they could no longer countenance it." (16)

Claire Louise Eustace has argued: "The subsequent press attention given to this militant protest publicized the demands of women suffragists to a degree that made existing organisations interested in suffrage re-examine their own campaigns. It also led to a dramatic increase in interest in the WSPU, and the formation of new branches in other areas of Britain, especially after it was decided to relocate the WSPU headquarters to London in 1906." (16a)

1906 Liberal Government

In the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won 399 seats and gave them a large majority over the Conservative Party (156) and the Labour Party (29). Pankhurst hoped that Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the new prime minister, and his Liberal government, would give women the vote. However, several Liberal MPs were strongly against this. It was pointed out that there were a million more adult women than men in Britain. It was suggested that women would vote not as citizens but as women and would "swamp men with their votes". (17)

Campbell-Bannerman gave his personal support to Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), though he warned them that he could not persuade his colleagues to support the legislation that would make their aspiration a reality. Despite the unwillingness of the Liberal government to introduce legislation, Fawcett remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. However, Pankhurst took a very different view. (18)

On 23rd October, 1906, Emmeline Pankhurst organised a huge rally in Caxton Hall, and a deputation went to the House of Commons to demand the vote: She later wrote about this in her autobiography, My Own Story (1914): "Those women had followed me to the House of Commons. They had defied the police. They were awake at last thev were prepared to do something that women had never done before - fight for themselves. Women had always fought for men, and for their children. Now they were ready to light for their own human rights. Our militant movement was established.'' (19)

To coincide with the opening of parliament on 13th February 1907 the WSPU organized the first Women's Parliament at Caxton Hall. The women were confronted by mounted police. Fifty-eight women appeared in court as a result of the conflict. Most of those arrested received seven to fourteen days in Holloway Prison, though Sylvia Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard got three weeks. (20)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Some leading members of the Women's Social and Political Union began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). (21)

In January 1908 Edith New and Ada Nield Chew chained themselves to the railings of 10 Downing Street. According to The Daily Express: "Each suffragist wore round her waist a long, steel chain - not unlike a very heavy dog chain. Each took the loosened end of the chain, threw it round the railings, and fixed it to the rest of the chain. This was done so deftly that it was not until the police heard the click of the lock that they understood the clever move by which the suffragists had outwitted them, and prevented for a time their own removal. Votes for women! shouted the two voluntary prisoners simultaneously. Votes for Women!" (21a)

In February, 1908, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and was sentenced to six weeks in prison. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause (2003), explained how she reacted to the situation: "Emmeline knew what to expect - she had by then heard graphic descriptions of prison life from Sylvia and Adela as well as from Christabel. She was shocked, though, when the wardress asked her to undress in order to put on her prison uniform - stained underwear, rough brown and red striped stockings and a dress with arrows on it. She was given coarse but clean sheets, a towel, a mug of cold cocoa and a thick slice of brown bread, and taken to her cell. Second division prisoners were kept in solitary confinement and were let out of their cells only for an hour's exercise each day. They were not allowed to receive letters for four weeks. Even though she had prepared herself for the experience, the reality hit her harder than she had anticipated." (22)

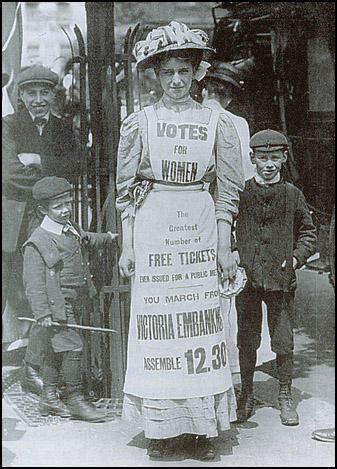

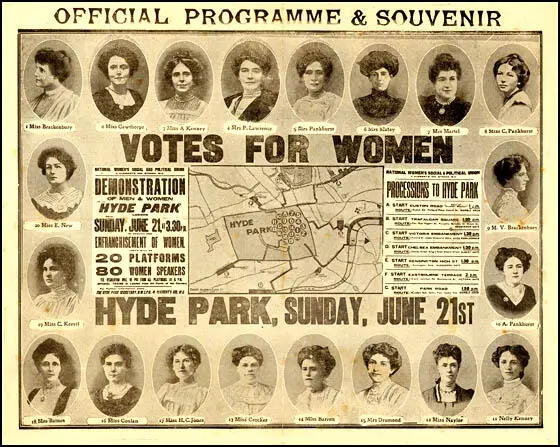

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond, Edith New and Gladice Keevil. (22x)

On 30th June, 1908, Edith New attended a public meeting in Parliament Square. The authorities decided to send in 5,000 foot police and 50 mounted men to break-up the meeting. Sylvia Pankhurst later reported: "Women spoke from the steps of the Government buildings and offices in Broad Sanctuary, they lifted themselves above the people by the railings round the Abbey Gardens and Palace Yard, or raised their voices standing among the crowds on road or pavement. They were torn by the harrying constables from their foothold and flung into the masses of people... Then roughs appeared, organized gangs, who treated the women with every type of indignity... I was obliged to drop my handbag with keys and purse, to have my hands free to protect myself. The roughs were constantly attempting to drag women down side streets away from the main body of the crowd... Enraged by the violence and indecency in the Square, Mary Leigh and Edith New took a cab into Downing Street, and flung two small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house." (22a) It was later revealed that these gangs had been hired by Scotland Yard. (22b)

The next day at Westminster police court twenty-seven women were sent to prison for terms varying from one to two months. Edith New and Mary Leigh, were sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In court the women wore white dresses and were relieved to hear the sentence because they feared it would be a much longer sentence. However, the Manchester Guardian protested in a leading article: "Their stringent imprisonment... violates the public conscience." (22c) However, Millicent Fawcett, leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), said later that it was this incident that resulted in her condemning the methods being used by the WSPU. (22d)

from Holloway to Queen's Hall on 23rd August 1908.

Edith New and Mary Leigh were released from prison on 23rd August. They were welcomed on release by a team of women in white dresses who drew their carriage from Holloway to Clements Inn. They were greeted by a brass band and accorded a ceremonial welcome breakfast attended by the two main leaders of the WSPU, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. 22e)

Hunger Strikes

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.” (23)

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail". (24)

On 22nd September 1909 Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh were arrested while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. Marsh, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force. (25)

Mary Leigh, described what it was like to be force-fed: "On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful - the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down - about a pint of milk... egg and milk is sometimes used." Leigh's graphic account of the horrors of forcible feeding was published while she was still in prison. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. (26)

Hunger-strikes now became the accepted strategy of the WSPU. In one eighteen month period, Emmeline Pankhurst endured ten hunger-strikes. She later recalled: "Hunger-striking reduces a prisoner's weight very quickly, but thirst-striking reduces weight so alarmingly fast that prison doctors were at first thrown into absolute panic of fright. Later they became somewhat hardened, but even now they regard the thirst-strike with terror. I am not sure that I can convey to the reader the effect of days spent without a single drop of water taken into the system. The body cannot endure loss of moisture. It cries out in protest with every nerve. The muscles waste, the skin becomes shrunken and flabby, the facial appearance alters horribly, all these outward symptoms being eloquent of the acute suffering of the entire physical being. Every natural function is, of course, suspended, and the poisons which are unable to pass out of the body are retained and absorbed." (27)

In November 1909, Theresa Garnett accosted Winston Churchill with a whip. She shouted "take that you brute", however, she later admitted she missed him. She was arrested for assault but was found guilty of disturbing the peace. Garnett was found guilty and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Horfield Prison. Her friend, Mary Blathwayt, wrote in her diary on 15th November: "Miss Garnett got one month for whipping Mr. Churchill across the face and not hurting him." The following day, her mother, Emily Blathwayt, wrote: The papers were full of Saint Theresa as we call her." Emily went onto say that the movement was "not altogether displeased" that the newspapers had headlines that were not true such as "Winston whipped" and "Churchill flogged". (28)

The Conciliation Bill

In January 1910, Herbert Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement". (29)

Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett both agreed to the idea and the WSPU declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. (30) Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated." (31)

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. Asquith made a speech where he made it clear that he intended to shelve the Conciliation Bill.

On hearing the news, Emmeline Pankhurst, led 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons on 18th November, 1910. Sylvia Pankhurst was one of the women who took part in the protest and experienced the violent way the police dealt with the women: "I saw Ada Wright knocked down a dozen times in succession. A tall man with a silk hat fought to protect her as she lay on the ground, but a group of policemen thrust him away, seized her again, hurled her into the crowd and felled her again as she turned. Later I saw her lying against the wall of the House of Lords, with a group of anxious women kneeling round her. Two girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two uniformed policemen. One of a group of officers in plain clothes ran up and kicked one of the girls, whilst the others laughed and jeered at her." (32)

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel." (32a)

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". (32b) However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct." (32c)

A new Conciliation Bill was passed by the House of Commons on 5th May 1911 with a majority of 167. The main opposition came from Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, who saw it as being "anti-democratic". He argued "Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife." (33)

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was officially in favour of woman's suffrage. However, he had told his close associates, such as Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP in West Ham North: "He (David Lloyd George) was very much disturbed about the Conciliation Bill, of which he highly disapproved although he is a universal suffragist... We had promised a week (or more) for its full discussion. Again and again he cursed that promise. He could not see how we could get out of it, yet he regarded it as fatal (if passed)." (34)

Lloyd George was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Herbert Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill." (35)

Millicent Fawcett still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose." (36)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament. (37)

On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians, H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged." (38)

The following month Millicent Fawcett wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them." (39)

Henry Brailsford went to see the Emmeline Pankhurst and asked her to control her members in order to get the legislation passed by Parliament. She replied "I wish I had never heard of that abominable Conciliation Bill!" and Christabel Pankhurst called for more militant actions. The Conciliation Bill was debated in March 1912, and was defeated by 14 votes. Asquith claimed that the reason why his government did not back the issue was because they were committed to a full franchise reform bill. However, he never kept his promise and a new bill never appeared before Parliament. (40)

Arson Campaign

Some members of the WSPU, including Adela Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence as a strategy. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU in October 1911. Sylvia Pankhurst was also critical of this new militancy. (41)

Margery Corbett was a member of the NUWSS when she met Emmeline and Sylvia in 1911. "I talked to Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Sylvia. I admired their wonderful courage, but when they started hurting other people, I had to decide whether I wanted to go on working with the constitutional movement, or whether I would join the militants. Eventually I decided to remain a constitutional." (42)

On 4th March 1912 the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU) organised a window-breaking demonstration in Whitehall. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence both disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. Records seized as evidence show the imtvitation sent out by Emmeline Pankhurst: "Men and women I invite you to come to Parliament Square on Monday, March 4th 1912 at 8 o'clock to take part in a 'Great Protest Meeting' against the government's refusal to include women in their reform Bill. Speeches will be delivered by well-known Suffragettes, who want to enlist your sympathy and help in the great battle they are fighting for human liberty." This vaguely-titled ‘Great Militant Protest' was a "skilfully planned secret attack" that would involve over 150 women armed with hammers, stones and clubs simultaneously smashing the windows of shops and offices in London's West End.

Victoria Lidiard from Bristol was one of the women who volunteered to take part in the demonstration. The severely disabled, May Billinghurst, agreed to hide some of the stones underneath the rug covering her knees. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent."

Victoria broke a window at the War Office. She later recalled: "He just looked at me. Meantime another policeman rushed up towards me and then an inspector on horseback came. So I was escorted to Bow Street, a policeman each side of me, clutching my arm. and one behind. Well, I had eight stones, but I'd only used one so on the way to the police station I dropped them one by one and to my amazement when I was taken down at Bow Street, this policeman that had followed put the seven stones on the table and said, She dropped these on the way." Victoria was one of 200 suffragettes who was arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration.

by Women's Social & Political Union members (4th March, 1912)

Victoria Lidiard got two months. Bella Hoffman has pointed out: "Her memory of Holloway was of one of her own sisters shouting encouraging messages from across the street, standing on a chair in her cell and singing out of the barred window, and the black beetle in her porridge." Under instructions from her mother, Victoria did not go on hunger-strike. As she later pointed out in a BBC interview, although she was willing to go to prison for women's suffrage, she was unable to disobey an order given by her mother.

The government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel Pankhurst escaped to France but Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU. (43)

Frederick Pethhick Lawrence was made to suffer force-feeding twice a day for ten days before his release: "The head doctor, a most sensitive man, was visibly distressed by what he had to do. It certainly was an unpleasant and painful process and a sufficient number of warders had to be called in to prevent my moving while a rubber tube was pushed up my nostril and down into my throat and liquid was poured through it into my stomach. Twice a day thereafter one of the doctors fed me in this way. I was not allowed to leave my cell in the hospital and for the most part I had to stay in bed. There was nothing to do but to read; and the days were very long and went very slowly." (44)

Emmeline Pankhurst was one of those arrested. Once again she went on hunger strike: "I generally suffer most on the second day. After that there is no very desperate craving for food. weakness and mental depression take its place. Great disturbances of digestion divert the desire for food to a longing for relief from pain. Often there is intense headache, with fits of dizziness, or slight delirium. Complete exhaustion and a feeling of isolation from earth mark the final stages of the ordeal. Recovery is often protracted, and entire recovery of normal health is sometimes discouragingly slow." After she was released from prison she was nursed by Catherine Pine. (45)

Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. (46)

Annie Kenney was put in charge of the WSPU in London. Every week Kenney travelled to France to receive Christabel's latest orders. Fran Abrams has pointed out: "It was the start of a cloak-and-dagger existence that lasted for more than two years. Each Friday, heavily disguised, Annie would take the boat-train via La Havre. Sundays were devoted to work but on Saturdays the two would walk along the Seine or visit the Bois de Boulogne. Annie took instructions from Christabel on every little point - which organiser should be placed where, circular letters, fund-raising, lobbying MPs... During the week Annie worked all day at the union's Clement's Inn headquarters, then met militants at her flat at midnight to discuss illegal actions. Christabel had ordered an escalation of militancy, including the burning of empty houses, and it fell to Annie to organise these raids. She did not enjoy this work, nor did she agree with it. She did it because Christabel asked her to, she said later." (47)

Christabel was aware that after the House of Lords had rejected the proposed 1831 Reform Act, a mob had attempted to burn down Nottingham Castle. She therefore asked Sylvia Pankhurst to carry out a similar attack. Sylvia later wrote: "The idea of doing a stealthy deed of destruction was repugnant... Though I knew she did not consider it so, I had the unhappy sense of having been asked to do something morally wrong. I replied that I should be willing to lead a torchlight procession to the castle, to fling my torch at it, and to call the others to do the same, as a symbolic act." Christabel was unimpressed and rejected the idea. (48)

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (49)

One of the first arsonists was Mary Richardson. She later recalled the first time she set fire to a building: "I took the things from her and went on to the mansion. The putty of one of the ground-floor windows was old and broke away easily, and I had soon knocked out a large pane of the glass. When I climbed inside into the blackness it was a horrible moment. The place was frighteningly strange and pitch dark, smelling of damp and decay... A ghastly fear took possession of me; and, when my face wiped against a cobweb, I was momentarily stiff with fright. But I knew how to lay a fire - I had built many a camp fire in my young days -a nd that part of the work was simple and quickly done. I poured the inflammable liquid over everything; then I made a long fuse of twisted cotton wool, soaking that too as I unwound it and slowly made my way back to the window at which I had entered." (50)

Annie Kenney was charged with "incitement to riot" in April 1913. She was found guilty at the Old Bailey and was sentenced to eighteen months in Maidstone Prison. Her deputy, Grace Roe, now became head of operations in London. She immediately went on hunger strike and became the first suffragette to be released under the provisions of the Cat and Mouse Act. Kenney went into hiding until she was caught once again and returned to prison. That summer she escaped to France during a respite and went to live with Christabel Pankhurst in Deauville. (51)

Christabel Pankhurst remained convinced that escalating violence would eventually win the parliamentary vote for women since it would create, she believed, an intolerable situation for politicians. In early January 1914, she asked Sylvia to travel to Paris where she told her that her East London Federation must be separate from the WSPU since it was allied to the socialist movement. (52)

Sylvia was also criticised for speaking on the same platform as the Labour Party MP, George Lansbury. Christabel told her: "You have your own ideas. We do not want that; we want all our women to take their instructions and walk in step like an army!" Sylvia later recalled: "Too tired, too ill to argue, I made no reply. I was oppressed by a sense of tragedy, grieved by her ruthlessness. Her glorification of autocracy seemed to me remote from the struggle we were waging." (53)

Christabel also told her sister that she must withdraw support from the Labour Party. She had now decided that the WSPU should not form any alliance with male politicians. Christabel wrote in The Suffragette: "For Suffragists to put their faith in any men's party, whatever it may call itself, is recklessly to disregard the lessons of the past forty years… The truth is that women must work out their own salvation. Men will not do it for them". (54)

Emmeline Pankhurst was now estranged from two of her daughters. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote to Sylvia Pankhurst about her mother: "I believe she conceived her objective in the spirit of generous enthusiasm. In the end it obsessed her like a passion and she completely identified her own career with it in order to obtain it. She threw scruple, affection, honour, legality and her own principles to the winds." (55)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, had argued for many years that women's suffrage was a necessary part of a socialist programme. However, MacDonald rejected the WSPU use of violence: "I have no objection to revolution, if it is necessary but I have the very strongest objection to childishness masquerading as revolution, and all that one can say of these window-breaking expeditions is that they are simply silly and provocative. I wish the working women of the country who really care for the vote ... would come to London and tell these pettifogging middle-class damsels who are going out with little hammers in their muffs that if they do not go home they will get their heads broken." (56)

In 1912 the WSPU began a campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. The main figure in this campaign was May Billinghurst. A fellow suffragette, Lilian Lenton, argued: "She (May Billinghurst) would set out in her chair with many little packages from which, when they were turned upside down, there flowed a dark brown sticky fluid, concealed under the rug which covered her legs. She went undeviatingly from one pillar box to another, sometimes alone, sometimes with another suffragette to do the actual job, dropping a package into each one." (57)

Billinghurst was eventually arrested at Blackheath preparing for a pillar-box raid. She seemed pleased about being caught as she told the police officer: "With all the pillar boxes we've done, there has been nothing in the papers about it - perhaps now there has been an arrest there will be something." Billinghurst appeared at the Old Bailey in January 1913. During the trial Billinghurst argued: "The government authorities may further maim my body by the torture of forcible feeding as they are torturing weak women in prison at the present time. They may even kill me in the process for I am not strong, but they cannot take away my freedom of spirit or my determination to fight this good fight to the end." (58)

In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses". (59)

The women responsible for these arson attacks were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act. (60)

On 24th February 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested for procuring and inciting persons to commit offences contrary to the Malicious Injuries to Property Act 1861. The Times reported: "Mrs Pankhurst, who conducted her own defence, was found guilty, with a strong recommendation to mercy, and Mr Justice Lush sentenced her to three years' penal servitude. She had previously declared her intention to resist strenuously the prison treatment until she was released. A scene of uproar followed the passing of the sentence." (61)

After going nine days without eating, they released her for fifteen days so she could recover her health. "They sent me away, sitting bolt upright in a cab, unmindful of the fact that I was in a dangerous condition of weakness, having lost two stone in weight and suffered seriously from irregularities of heart action." On 26th May, 1913, when Emmeline Pankhurst attempted to attend a meeting, she was arrested and returned to prison. (62)

Rachel Barrett and other members of staff were arrested while printing The Suffragette newspaper. Found guilty of conspiracy she was sentenced to nine months imprisonment. She immediately began a hunger strike in Holloway Prison. After five days she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Barrett was re-arrested and this time went on a hunger and thirst strike. When she was released she escaped to Edinburgh. After a meeting with Christabel Pankhurst in Paris, it was decided to publish the newspaper in Scotland. (63)

In June, 1913, at the most important race of the year, the Derby, Emily Davison ran out on the course and attempted to grab the bridle of Anmer, a horse owned by King George V. The horse hit Emily and the impact fractured her skull and she died without regaining consciousness. Although many suffragettes endangered their lives by hunger strikes, Emily Davison was the only one who deliberately risked death. However, her actions did not have the desired impact on the general public. They appeared to be more concerned with the health of the horse and jockey and Davison was condemned as a mentally ill fanatic. (64)

During this period Kitty Marion was the leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign and she was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House at St Leonards (April 1913), the Grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse (June 1913) and various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred followed by release under the Cat & Mouse Act. It has been calculated that Marion endured 200 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike. (65)

The Great Scourge

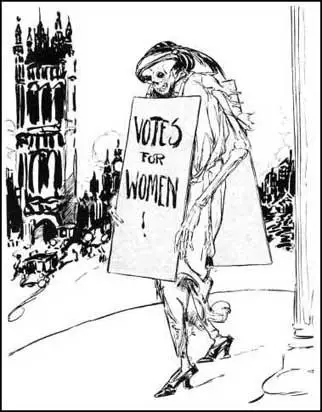

Sylvia Pankhurst became increasing disillusioned with Christabel's approach to the suffrage campaign. "Votes for women and chastity for men became her favourite slogan... She alleged that seventy-five to eighty per cent of men become infected with gonorrhea, and twenty to twenty-five per cent with syphilis, insisting that only an insignificant minority escaped infection by some form of venereal disease. Women were strongly warned against the dangers of marriage, and assured that large numbers of women were refusing it. The greater part, both of the serious and minor illnesses suffered by married women... she declared to be due to the husband having at some time contracted gonorrhea Childless marriages were attributed to the same cause. Syphilis she declared to be the prime reason of a high infantile mortality." (66)

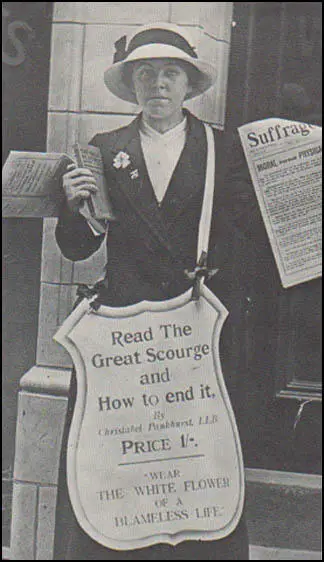

Christabel Pankhurst wrote several articles in The Suffragette on the dangers of marriage. Christabel's articles were reissued as a book entitled, The Great Scourge and How to End It (1913). She argued that most men had venereal disease and that the prime reason for opposition to women's suffrage came from men concerned that enfranchised women would stop their promiscuity. Until they had the vote, she suggested that women should be wary of any sexual contact with men. (67)

Dora Marsden criticised Christabel Pankhurst for upholding the values of chastity, marriage and monogamy. She also pointed out in The Egoist that Pankhurst's statistics on venereal disease were so exaggerated that they made nonsense of her argument. Marsden concluded the article with the claim: "If Miss Pankhurst desires to exploit human boredom and the ravages of dirt she will require to call in the aid of a more subtle intelligence than she herself appears to possess." (68) Other contributors to the journal joined in the attack on Pankhurst. Dora Foster Kerr argued that "her obvious ignorance of life is a great handicap to Miss Pankhurst". (69) Whereas Ezra Pound suggested that she "has as much intellect as a guinea pig" (70).

Rebecca West, a leading feminist and suffrage campaigner, was also appalled by Christabel's views on sex. "I say that her remarks on the subject are utterly valueless and are likely to discredit the Cause in which we believe... The strange uses to which we put our new-found liberty! There was a long and desperate struggle before it became possible for women to write candidly on subjects such as these. That this power should be used to express views that would be old-fashioned and uncharitable in the pastor of a Little Bethel is a matter for scalding tears." (71)

Decline of the WSPU

Several friends became worried about Christabel's mental state. A number of significant figures in the WSPU left the organisation over the arson campaign. This included Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford, Laura Ainsworth, Eveline Haverfield and Louisa Garrett Anderson. Leaders of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage such as Henry N. Brailsford, Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman, argued "that militancy had been taken to foolish extremes and was now damaging the cause". (72)

Hertha Ayrton, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Janie Allan and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson stopped providing much needed money for the organization. Colonel Linley Blathwayt and Emily Blathwayt also cut off funds to the WSPU. In June 1913 a house had been burned down close to Eagle House. Under pressure from her parents, Mary Blathwayt resigned from the WSPU. (73)

In February 1914, Christabel expelled Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst from the WSPU for refusing to follow orders. Beatrice Harraden, a member of the WSPU since 1905, wrote a letter to Christabel calling on her to bring an end to the arson campaign and accusing her of alienating too many old colleagues by her dictatorial behaviour: "It must be that... your exile (in Paris) prevents you from being in real touch with facts as they are over here." (74)

Henry Harben complained that her autocratic behaviour had destroyed the WSPU: "People are saying that from the leader of a great movement you are developing into the ringleader of a little rebel Rump." (75) According to Martin Pugh "she had fallen into the error of all autocratic leaders; her power to manipulate personnel was so complete that it left her increasingly surrounded by sycophants who lacked real ability." (76)

On 10 March 1914 Mary Richardson attacked a painting, Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery. She later described what happened: "I dashed up to the painting. My first blow with the axe merely broke the protective glass. But, Of course, it did more than that, for the detective rose with his newspaper still in his hand and walked round the red plush seat, staring up at the skylight which was being repaired. The sound of the glass breaking also attracted the attention of the attendant at the door who, in his frantic efforts to reach me, slipped on the highly polished floor and fell face downward. And so I was given time to get in a further four blows with my axe before I was, in turn, attacked." (77)

The Manchester Guardian reported the following day: "At the National Gallery, yesterday morning, the famous Rokeby Venus, the Velasquez picture which eight years ago was bought for the nation by public subscription for £45,000, was seriously damaged by a militant suffragist connected with the Women's Social and Political Union... The woman, producing a meat chopper from her muff or cloak, smashed the glass of the picture, and rained blows upon the back of the Venus. A police officer was at the door of the room, and a gallery attendant also heard the smashing of the glass. They rushed towards the woman, but before they could seize her she had made seven cuts in the canvas. (78)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (79)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (80)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (81)

In October 1915, The WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral." (82)

Anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans". Another article on the Union of Democratic Control carried the headline: "Norman Angell: Is He Working for Germany?" Mary Macarthur and Margaret Bondfield were described as "Bolshevik women trade union leaders" and Arthur Henderson, who was in favour of a negotiated peace with Germany, was accused of being in the pay of the Central Powers. Her daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, who was now a member of the Labour Party, accused her mother of abandoning the pacifist views of Richard Pankhurst. (83)

Adela Pankhurst also disagreed with her mother and in Australia she joined the campaign against the First World War. Adela believed that her actions were true to her father's belief in international socialism. She wrote to Sylvia that like her she was "carrying out her father's work". Emmeline Pankhurst completely rejected this approach and told Sylvia that she was "ashamed to know where you and Adela stand." (84) Sylvia commented: "Families which remain on unruffled terms, though their members are in opposing political parties, take their politics less keenly to heart than we Pankhursts." (85)

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. Lilian Lenton, who had played an important role in the militant campaign later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30." (86)

Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst now dissolved the Women's Social & Political Union and formed The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (i) A fight to the finish with Germany. (ii) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (iii) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." (87)

Primary Sources

(1) Emmeline Pankhurst described the formation of the Women's Social and Political Union in her book My Own Story (1914).

It was on October 10, 1903 that I invited a number of women to my house in Nelson Street, Manchester, for purposes of organisation. We voted to call our new society the Women's Social and Political Union, partly to emphasize its democracy, and partly to define its object as political rather than propagandist. We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. "Deeds, not Words" was to be our permanent motto.

(2) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

I was determined to join the Pankhursts' organisation, the Women's Social and Political Union, but was held up in this resolve for three months by the fact that my father, who had considerable foresight and realised pretty well what joining that body was likely to mean, was inclined to be opposed to the idea. However, I finally decided that he could be no judge of a matter which concerned one primarily as a woman. Prid meanwhile had, travelling by a slightly different road, arrived at the same conclusion. She and I met one autumn day in London, and, full of excitement, went off together to Clement's Inn and joined.

(3) Emmeline Pankhurst, My Own Story (1914)

The Women's Social and Political Union had been in existence two years before any opportunity was presented to work on a national scale. The autumn of 1905 brought a political situation, which seemed to us to promise bright hopes for women's enfranchisement. The life of the old Parliament was coming to an end, and the country was on the eve of a general election in which the liberals hoped to be returned to power… The only object worth trying for was pledges from responsible leaders that the new Government would make women's suffrage a part of the official programme.

(4) William Stead, The Review of Reviews (November, 1906)

A deputation from the Woman's Social and Political Union waited upon the Prime Minister to urge upon him the importance of conceding the vote to women. As Sir Henry refused to do anything, a few of the more determined leaders of the movement made a demonstration in the outer Lobby. It was a very harmless affair. A few sentences of indignant protest, promptly cut short by the police, fell from the lips of the first speaker. Mrs. Despard, sister of General French, a grey-haired matron who has devoted herself to charitable works in South West London, promptly took the place of the silenced speaker, only to be as promptly silenced. The police then removed the protesting ladies, and there the incident ought to have ended. But no sooner were the women removed from the precincts of Parliament than several of them were arrested, including at least one bystander, Miss Annie Kenney, who had never been in the Lobby at all, and who had refrained from taking any part in the demonstration. Mrs. Despard, who was one of the chief offenders, protested against Miss Kenney's arrest, declaring that if any one deserved arrest it was herself. The police, however, refrained from arresting General French's sister, saying that they had their instructions. So Miss Kenney, the factory girl was marched off to prison, while Mrs. Despard was left at liberty, in order apparently to demonstrate that even in dealing with women there is one law for the rich and another for the poor.

Next day the ladies were brought before the Westminster police magistrate. They were not represented by counsel, and they one and all declared that they ignored the jurisdiction of the Court. They regarded themselves as outlaws, shut out from the pale of the Constitution. Several persons who had witnessed the proceedings tendered themselves as voluntary witnesses, but they were not allowed to give their evidence. The police, therefore, had everything their own way, and the magistrate convicted the whole batch, ordering them to enter into recognizances and bind themselves over to keep the peace for six months. As they refused to do anything of the kind they were ordered to be imprisoned as ordinary criminal convicts for two months. One of the Misses Pankhurst, who was accused of attempting to make a disturbance outside the Court, was sentenced to a fortnight's imprisonment on the evidence of the police, which was flatly contradicted by three independent respectable witnesses. The prisoners were then removed from Court and conveyed in Black Maria to Holloway Gaol. The most disreputable feature of the proceedings was the deliberate and malignant misrepresentation of the conduct of the accused by the hooligans of some of the daily papers. The cowardly brutality of some of the scoundrels who lend their pens to this campaign of calumny is a melancholy illustration of the extent to which some newspapers are staffed by Yahoos.

The ladies, on arriving at Holloway Gaol, were treated exactly as if they had been the drabs of the street convicted for drunkenness. They were stripped, deprived of their own raiment, made to wear the clothes, none too clean, of previous prisoners, and shut up in verminous cells in solitary confinement. Two of their number, Mrs. Pethwick-Lawrence, the wife of the last proprietor of the Echo, and Mrs. Montefiore, broke down in health. To avert fatal consequences their medical advisers insisted that they should enter into recognizances for good behaviour and regain their liberty. One of the others who was ill was sent into the hospital. The others, among them Mrs. Cobden-Saunderson, a daughter Richard Cobden, stood firm and took their gruel without complaint. They were prepared to "stick it through" to the end. Neither they nor any of their representatives made any appeal to the Government for any amelioration of their condition. They protested vigorously to the Governor against the filthy state of their cells. Tardy measures were taken to extirpate the bugs from which less distinguished prisoners have long suffered, but they were less successful in their protests against the rats and mice. When I was at Holloway as a first-class misdemeanant twenty years ago, one of my liveliest recollections is that of mice running over my head as I lay in bed. Things do not appear to have improved much since then.

(5) William Stead, The Review of Reviews (June, 1910)

Saturday, June 18th, promises to be a memorable day in the history of Woman's Suffrage. Since the General Election the militants have postponed the threatened resumption of warlike tactics in order to give a fair opportunity to the tactics of ordinary peaceful, law-abiding demonstration. They are as keen as ever for admission within the pale of the Constitution, but they have been told that after 480 of their number have proved the sincerity of their enthusiasm by going to gaol there is no need now for anything more sensational than a great procession through the streets of London and a united demonstration in Albert Hall. Although the older, not to say the ancient, Union which bore the burden and heat of the day before the advent of the Suffragettes is not to be officially represented in the procession - much to our regret - most of their members will probably be in the ranks. This is emphatically an occasion on which all advocates for woman's emancipation should sink their differences and present a united front to the enemy. I sincerely hope that all my Helpers and Associates who may be in town will not fail to fall into line and spare no effort to make the procession of June 18th one of those memorable demonstrations of political earnestness which leave an indelible impression on the public mind. That the Women will obtain enfranchisement in this Parliament I do not venture to hope. But the days of the present Parliament are numbered, and the prospects of success in the next will largely depend on the impression of orderly, well-disciplined enthusiasm which London will receive from this midsummer procession.

(6) Christabel Pankhurst, Unshackled (1959)

Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded. Mr. Gladstone did not reply, but after she had fasted ninety-one hours, Miss Wallace Dunlop was set free. She was in an exhausted state, having refused every threat and appeal to induce her to break her fast.

(7) Teresa Billington Greig, The Non-Violent Militant (1987)

The first militant protest was decided upon by Miss Christabel Pankhurst, and announced by mother or daughter to a small number of the more active members of the Union. The body of members knew nothing of the plans until they heard with the public that it had been carried out… It was at this point that the sense of difference of outlook, of which I had always been conscious in my association with Mrs. Pankhurst and her daughter, became acute. I did not approve the line of protest determined upon. It seemed to me to provide a very inadequate outlet for the expression of our rebellion.

(8) Christabel Pankhurst, Unshackled (1959)

Eighty-one women were still in prison (March, 1912), some for terms of six months… Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed.

(9) Dora Montefiore, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927)

The next episode in this eventful year of unavoidable publicity in the women’s cause was the occasion in October, 1906, of our meeting as militant suffragists in the Lobby of the Houses of Parliament with the object of asking the Prime Minister to receive a deputation. It was agreed that if this request was refused several of us should get up on seats and make speeches for “Votes for Women.” Our request was refused, and we began to carry out our subsequent programme. Naturally after the first horror-struck moments of surprise at women daring to voice their wrongs in the very sanctuary of male exclusiveness, the uniformed guardians of the shrine rushed forward to cleanse the sacred spot from such pollution. The women speakers were dragged from their extemporised rostrums and were pushed down the galleries leading from the Lobby towards the Abbey entrance, and with little consideration were spurned down the steps on to the pavement. I was one of those thus ejected. My arm was twisted up against my back by a very strong-muscled policeman, and when I was released at the bottom of the steps of Westminster Hall, and had recovered from the pain of the operation, I turned round and watched the unwilling exit of crowds of other women. At a certain moment in the proceedings I saw Mrs. Despard standing at the top of the steps with a policeman just behind her, and fearing that a woman of her age might be injured by the rough-and-tumble methods which the police, under orders, were executing, I called out to some of the Members and onlookers who were mixed with us women at the foot of the stairs: “Can you men stand by and see a venerable woman handled in the way in which we have just been handled?” I was not allowed to say more, for Inspector Jarvis (who, however. I cannot fail to recall was on many occasions an excellent friend of mine, and who I know was in many respects in sympathy with much of our militant action), remarked to two constables standing near: “Take Mrs. Montefiore in; she is one of the ringleaders.” This “taking me in” meant marching me between two stalwart policemen to Cannon Row police station, where I was placed in a fairly large room and was soon joined by groups of excited and dishevelled militants. This was the beginning, in London, of a form of militancy which I always deprecated, the resistance to the police when being arrested, and struggles with police in the streets. I held that our demonstrations were necessary, and of great use in educating an apathetic public, but for women who are physically weaker than men to pit their strength against police who are trained in the use of physical violence, was derogatory to our sex and useless, if not a hindrance; to the cause for which we stood. When, therefore, some of my younger friends and fellow-workers were pushed into the waiting-room at Cannon Row, with their hair down and often with their clothing torn, I did my best to make them once more presentable, so that we should not appear in the streets as a dishevelled and very excited group of women. I held then, and have never ceased to hold the opinion, that even when demonstrating in the streets or when committing unconventional actions such as speaking in the Lobby of the House, we should always be able to control our voices and our actions and behave as ladies, and that we should gain much more support from the general public by carrying out this line of action. I should like to state here that I personally, except during the Lobby incident, never had to complain of the attitude of the police towards myself. In fact, I often found them helpful and sympathetic, as I shall have occasion later to relate.

After we had all been charged, and while stared at by special police, who were called in to identify us in case of future trouble, we were released on the understanding that we were to appear at the Westminster Court on the following morning. There we found that the charge against us was that of using “violent and abusive language.” Of course, every prisoner must be charged for some definite offence, and as the authorities could not discover that we had committed any of the definite offences in the criminal code, but had only begun to make speeches asking for votes for women, they put down the charge at random as that of “using violent and abusive language.” Each of us was asked in turn what we had to say in answer to the charge, and as I had with me the banner that had hung in front of my house during the “income tax siege,” I held it up first to the Magistrate and then for the Court to see. On it was inscribed: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” A constable snatched the banner from me and the proceedings continued. When the police, being asked for evidence of the breach of the laws which we had committed, were questioned definitely as to what they had heard, they each repeated that we had “asked for votes for women.” Their intellectual equipment was not equal to the task of repeating any of the arguments we had begun to unfold in the Lobby, but “Votes for Women” having by this time become a slogan, they were able to repeat that one sentence, though none of them looked particularly smart or happy as they did so. The proceedings were entirely farcical. The Magistrate consulted with others around him and tried to look very solemn and we were told that we were each to be bound over in the sum of £10 to keep the peace in future. This we all of us refused to do, as we did not consider we had broken the peace, or committed any offence for which we should be bound over. It was then explained to us that the alternative was two months’ imprisonment, and this alternative we accepted. We were once more taken from the Court and shut into a fair-sized room, where we were to be allowed to see friends and relatives, before being taken off to Holloway. As I, with the others, was leaving the Court, I said to the constable who was shepherding us, “I’m sorry to have lost that banner; it hung outside my house during the whole of the Hammersmith siege.” He grinned, but did not appear to be unfriendly, and as we filed into the room within the precincts of the Court, where we had to await “Black Maria,” he pushed the banner into my hands, and said: “It’s all right; here’s your banner.” As my daughter was married and not at the moment in very good health, I did not wish to add to her sufferings on my behalf by sending a summons asking her to come and see me at the Court. My son was working in an engineering business at Rochester and I also wished to save him from more trouble than I realised he was bound to have on my behalf. My brothers and sisters were mostly apathetic about, or hostile to my militant work, so I determined to send for no one of my own relatives, but I was surrounded by many good friends and fellow-workers who had come to give us a word of cheer. Towards evening “Black Maria” arrived at the Court and we were driven off to Holloway. “Black Maria” is a somewhat springless vehicle divided into compartments, so each prisoner is separated, though it is possible to speak to the prisoners immediately around one. It is used for conveying night after night the sweepings of the streets in the shape of drunkards and prostitutes from the Courts where they have been convicted, to Holloway Gaol. It can therefore be understood that it is neither a desirable nor a wholesome vehicle in which to travel. On arrival at Holloway we were each placed in some sort of sentry boxes with seats, and the woman who acted as receiving wardress opened one door after another and took down the details connected with the charge, and the status of the prisoner. She was of decided Irish extraction and the questions she put to us each in succession were to this effect: “Now then, gurrl, stand up! What’s your name, what’s your age, how do you get your livin’?” etc. etc. When all these questions had been answered to the satisfaction of this lady, we were told to leave our compartments and stand in a passage, where we were ordered to strip to our chemises or combinations and then to await further orders. The next scene was taking down our hair and searching rather perfunctorily our heads for possible undesirable inhabitants, after which a prison chemise, made of a sort of sacking, and generously stamped with the broad arrow, was handed to each of us, and I found myself exchanging my warm wool and silk combinations for this decidedly chilly and ungainly garment. The bath ordeal was not serious; we had only to stand in a few inches of doubtful-looking warm water and then put on the various articles of prison clothing provided for us. Each of us had a flannel petticoat made with enormous pleats round the waist, a dress of green serge made on the same ample lines and an apron, a check duster, which we were told was the handkerchief supplied, and a small green cape made with a hood, for out-door exercise, and a white linen cap tied under the chin. Thus arrayed our little party consisting of Mrs. How Martyn, Miss Irene Miller, Miss Billington, Miss Gauthorp, Mrs. Baldock, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence, Miss Annie Kenney, Miss Adela Pankhurst, Mrs. Cobden Saunderson and myself, met in one of the passages where our yellow badges bearing the numbers under which we were each to be known while in prison were handed out to us. We then underwent another and more detailed interrogatory, in which came the question: “What religion?” When I replied “Freethinker,” the wardress remarked “Free-what?” “That is no religion, you will be Protestant as long as you remain here”; and part of my description card fastened outside my cell contained the word “Prot.” We were then shut up in our respective cells with a cup of cocoa and a piece of bread and left for the night.

Much was written at the time about Holloway and the conditions under which prisoners lived during the time they were working out their sentences, and as I believe that something has been done to improve conditions since we militants made our protest by allowing ourselves to be imprisoned there, I want to put on record quite dispassionately and as of historical interest the sort of cells and the sort of surroundings accorded to women prisoners in October, 1906.