Hilda Dallas

Hilda Mary Dallas was born in Japan on 6th February 1878. Her father Charles Dallas was teaching English to Japanese students.

In 1901 she became a student at the Slade School of Art. Hilda who was described as ‘a handsome fair-haired girl' became the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) organizer for South St Pancras.

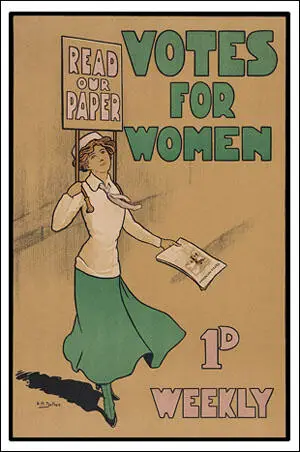

In 1909 she joined forces with Alfred Pearse and Laurence Housman to form the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage). The WSPU established its own newspaper, Votes for Women in October 1907. Its first editors were the husband and wife team of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. The newspaper was printed by the St. Clement's Press. It was originally a monthly but after April 1908 it was published every week. At this time sales reached 5,000 copies a month.

In 1907 some leading members of the WSPU began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. In a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference.

As a result of this speech, Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Margaret Nevinson and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Dallas remained close to people in the WFL but remained a member of the WSPU.

Hilda Dallas produced two posters to promote the Votes for Women. Permanent pitches were established in major cities to sell the newspaper. The Suffragette Bus, that toured the streets of London, also advertised the paper. By 1910 the circulation of the newspaper had increased to 30,000 a week. The newspaper was funded by the Pethick-Lawrences and all attempts to make a profit from the venture was abandoned in May, 1908 when it was decided to reduce the price from 3d to 1d.

At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

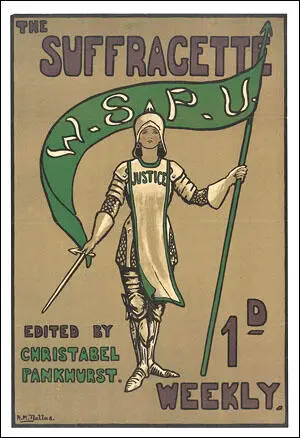

As a result of this expulsion, the WSPU lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, The Suffragette. Dallas produced a poster for the newspaper. Initially, the circulation of the newspaper was about 17,000. The Home Office tried to suppress the newspaper. On 2nd May 1913 Sidney Granville Drew, the managing director of Victoria House Printing Company which printed the newspaper, was arrested.

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

Dallas did not agree with this approach to the First World War and as a result she left the WSPU. She became a pacifist and produced and designed set & costumes for the 1929 Court Theatre production of the anti-war satirical play The Rumour that had been written by C. K. Munro.

Hilda Dallas died in 1958.

Primary Sources

(1) Angela V. John, Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009)

The WSPU's official newspaper had first appeared in October 1907 as a monthly newspaper. It soon expanded and became a popular penny weekly. At its height between forty and fifty thousand copies were sold weekly though it was read by many more. Evelyn Sharp had contributed to the paper since its early days. Pethick-Lawrence commented how her articles "had a pungency all her own without a trace of malice."

Now she was the salaried editor with responsibility for the paper's production. Volunteers helped prepare the newspaper's layout as well as pack and despatch. Contributors were not paid. Evelyn was keen to get people who did not usually write for the paper, including authors, politicians and ordinary supporters, to offer something.

(2) Edith Craig, The Vote (12th March, 1910)

It was seeing Votes for Women sold in the street in an apologetic manner that made me feel that I wanted to do it quite differently, and I began joining societies right away. That was some time ago, you know, and our sellers don't apologise for their existence now...

I love it. But I'm always getting moved on. You see, I generally sell the paper outside the Eustace Miles Restaurant, and I offer it verbally to every soul that passes. If they refuse, I say something to them. Most of them reply, others come up, and we collect a little crowd until I'm told to let the people into the restaurant, and move on. Then I begin all over again.