Suffrage Atelier

Alfred Pearse, Laurence Housman and Clemence Housman formed the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage) on 8th May 1909. (1) It claimed: "The object of the society is to encourage Artiststo forward the Women's movement, and particularly the Enfranchisement of Women, by means of pictorial publications. Each member of the Society shall undertake to give the Society first refusal of any pictorial work intended for publication, dealing with the women's movement. In return the artist will receive a certain percentage of the profits arising from the sale of her or his work." (2)

As Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) has pointed out that along with the Artists' Suffrage League: "Women were able to organise collectively and contribute their professional skills to the suffrage campaign. They designed, printed and embroidered all manner of political material; they taught each other the requisite skills from hand-painting to needlework; they designed major demonstrations and took part in them in their own contingents; they lent their studios for meetings and contributed to exhibitions, bazaars and fund-raising activities." (3)

Catharine Courtauld

Catharine Courtauld was one of the Suffrage Atelier's most active members. Her brother, Samuel Courtauld, was the head of the Courtauld textile business. (4) An art collector, he later founded the Courtauld Institute. (5) Catherine established herself as an artist living at 4a Upper Baker Street, London. On two occasions Catharine Courtauld exhibited her sculpture at the London Salon that had been established by the Allied Artists Association. (6)

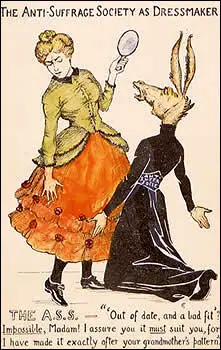

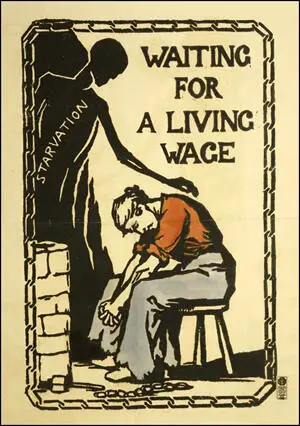

In 1908 Catharine Courtauld joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. The following year she joined the Suffrage Atelier. Several of her designs, such as The Anti-Suffrage Ostrich (c.1909), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Portrait Painter (c.1912), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Prophet (c.1912), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Dressmaker (c.1912), The Prehistoric Argument (1912) and Waiting for the Living Wage (c. 1913) were produced as postcards. (7) Her monogram was usually "c" within a larger "C". (8)

Alfred Pearse

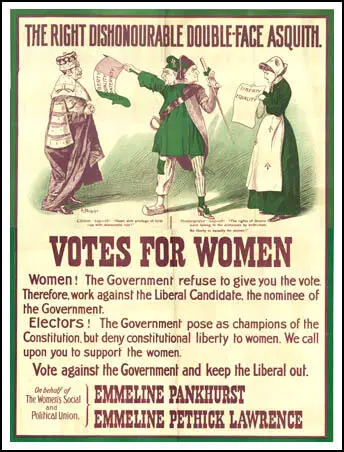

Alfred Pearse, a strong supporter of women's suffrage, was one of the founders of the Suffrage Atelier. Pearse composed a weekly cartoon for the Women Social & Political Union newspaper, Votes for Women from 18th February 1909. (9) One of his most important cartoons depicts the force-feeding of an imprisoned suffragette on a hunger strike - "a practice that the government authorized in 1909". (10)

Most of the Women Social & Political Union posters published between 1909-1914 that survive are signed by Alfred Pearse or in his style. Pearse was a highly competent illustrator, and his drawings for The Vote, Votes for Women and The Suffragette, using the name "A Patriot", helped to give the suffrage newspapers their attractive and professional tone. It seems that Pearse did not charge women's groups for his work. (11) Some of his drawings were issued as postcards. Pearse also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (12)

Laurence and Clemence Housman

The Suffrage Atelier was based at 1, Pembroke Cottages, Edwardes Square, the home of Laurence Housman and Clemence Housman. Laurence described his sister as the organistion's "chief worker" and the main "banner-maker" of the women's suffrage campaign. (13) In 1911 she made a new banner for the Actresses' Franchise League. "Stencilled in the AFL colours of pink, white, and green, it shows the twin masks of tragedy and comedy framed with wreaths and ribbons." (14)

Laurence and Clemence were two of seven children of Edward Housman (1831–1894), a solicitor, and his wife, Sarah Jane Williams (1828–1871). There brother was the poet, Alfred Edward Housman. Assisted by a legacy of £500 each, Laurence and Clemence moved to London in November 1883. They found lodgings at 36 Camberwell New Road. Clemence had been working long hours as a clerk for her father, but now gained employment as a wood-engraver, at first providing illustrations for such weekly illustrated papers as The Graphic and the Illustrated London News. (15)

Laurence Housman studied art at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal College of Art. A talented illustrator, his work was exhibited at the Baillie Gallery, the Fine Art Society, and the New English Art Club. His best known work includes Goblin Market (1893) and The Sensitive Plant (1898). He also published two volumes of poetry, Green Arras (1896) and Spikenard (1898). In 1900 he created great controversy when he published An Englishwoman's Love Letters. It was very successful and it is claimed he received over £2,000 in royalties. During this period he also worked as an art critic for the Manchester Guardian. (16)

Laurence and Clemence both worked tirelessly for women's suffrage. Laurence had been converted to the cause by hearing a speech given by Emmeline Pankhurst. This resulted in him developing "that most uncomfortable thing a social conscience." He added "I was forced, against my inclination, into a higher standard of moral courage than I had ever practised before" and this began his involvement in the "political problems and controversies of the present day." (17)

In 1907, Laurence Housman joined with several other left-wing intellectuals, including Henry Nevinson, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Henry Harben, Gerald Gould and Charles Mansell-Moullin to formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." (18)

In a speech made in June, 1909, Laurence Housmen outlined the importance of the Suffrage Atelier. He argued that art had longed suffered from a lack of connection with life in this country. "Pre-Raphaelitism had been an attempt to re-unite art and national life, but the growth of internationalism in technique had not been connected with any international idea or inspiration, such as the Women's Movement now supplied. The pageants of the present day, the revival of old folk-song and dance, and of something resembling a national costume in the purple, green, and white – or green, gold, and white of the Suffrage societies, were signs of the renewal of the blending of art and life." He added that when England invaded other countries "it was represented by John Bull, but when a really national crisis intervened the national spirit was symbolised by Britannia, the woman. Our representative house, in its more heroic moods, called itself the 'Mother of Parliaments'; at present it resembled rather an absconding father." (19)

Housmen's friends accused him of becoming obsessed with the subject of women's suffrage. The author, Alfred Sutro commented in his memoirs that "he was full of high spirits till he became an ardent advocate of 'Votes for Women', an admirable cause that seemed to have a somewhat depressing effect upon its more enthusiastic adherents" (20) The composer Arnold Bax recalled visiting Housman's home and seeing every room hung with suffrage slogans "like Christmas decorations" and that it "was almost the only topic of conversation". (21)

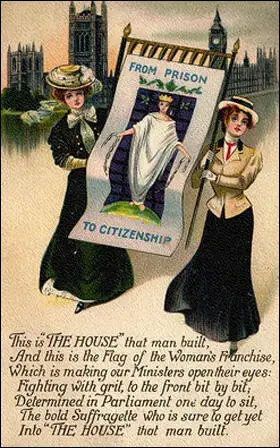

Clemence Housman was heavily involved in the making banners for the Women's Coronation Procession march through London on 17th June 1911, just before King George V's coronation. This included the banner "From Prison to Citizenship" under which "almost 1,000 ex-prisoners marched". The banner was made by Clemence from a design by Laurence Housman. The banner was described by Laurence in a letter to his friend Janet Ashbee: "My banner for the Kensington WSPU is practically finished. Everybody says it is the most beautiful that has been done." (22)

Votes for Women commented: "The Kensington Union banner designed by Mr Laurence Housman and worked by the members of the Union, showed the symbolic figure of a woman with broken fetters in her hand, and the words: 'From Prison to Citizenship'. The figure is in white on a purple ground, across which are trailing green leaves." (23) It was such an impressive design that it was featured on a postcard that was published in a series of twelve entitled, "The House that Man Built." (24)

by Clemence Housman from a design by Laurence Housman (1911)

Elizabeth Oakley, the author of Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence and Laurence Housman (2009) has argued: "The banners that Clemence and her friends worked so hard to produce must have been among the most eye-catching creations of the Atelier. By using the traditional sewing associated with women's place in the home as propaganda to free them from it, the Atelier had a subversive agenda." (25)

As Mary Lowndes pointed out in her pamphlet On Banners and Banner-Making that in the past it had been women's work to make colourful banners for men to go to war throughout the centuries but for the first time in history such banners were being used "to illumine women's own adventure". She added: "A banner is not a placard... a banner is a thing to float in the wind, to flicker in the breeze, to flirt its colours for your pleasure, to half show and half conceal a device you long to unravel: you do not want to read it, you want to worship it." (26)

As well as being a key member of the Suffrage Atelier, Clemence Housman was active in the Women Social & Political Union and on the committee of the Women's Tax Resistance League. On 30th September 1911 she was the first woman to be arrested for refusing to pay inhabited house duty. When she refused to pay the fine she was sent to prison. The case received a great deal of publicity in the newspapers. "She was released after a week, no reason being given, and did not pay her debt until she received the right to vote." (27)

Louise Rica Jacobs

Louise Rica Jacobs was educated at home by a live-in governess, before studying at the Hull School of Art and in 1903 she was awarded a Government free studentship at the Royal College of Art. A winner of a National silver medal and book prize for figure design in tempera and in 1905 a prize for "the best set of sketches in black and white" awarded in a competition held by the RCA Sketching Club. (28)

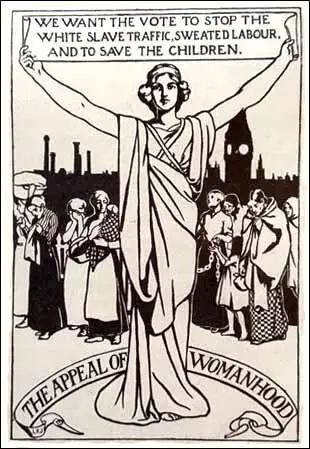

Jacobs became a member of the Suffrage Atelier and designed the "Appeal of Womanhood" for the Coronation Procession which cited the impelling reasons why women wanted the vote - "To stop the White Slave Traffic, Sweated Labour and to Save the Children". According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018): "The Appeal of Womanhood was issued both as a black and white postcard, which is sometimes found partially coloured, and, in at least two colourways, as a poster. The image was also emblazoned on a banner carried by the 'Brown Women' on their Edinburgh to London march in the autumn of 1912." (29)

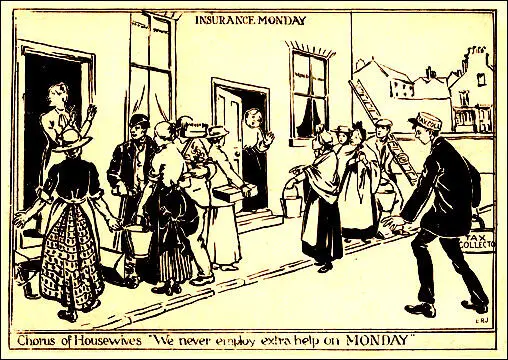

Louise Rica Jacobs was a member of Women's Freedom League (WFL) and provided drawings for The Vote. This included "Chorus of Housewives" that appeared on the front-page of the newspaper in December 1912 and signed "LRJ". (30) This drawing refers to the insurance provisions introduced by David Lloyd George under the 1911 Insurance Act by which domestic employers had to pay for insurance stamps for their servants. (31)

Jacob's cartoon was supporting the Women's Tax Resistance League whose members refused to pay several different taxes including national insurance, Imperial taxes dog licences, duties on carriages and carts and inhabited house duty. In other branches, members tended to make their resisting colleagues' cases the focus of particular campaigns, as in Brighton where the entire branch rallied to support the actions of their secretary and treasurer who had their goods seized and in lieu of their uncollected inhabited house duty in Edinburgh the members resisted paying taxes on the branch's bank interest, and amiably dismissed the Sheriff Officer when "he called to expostulate with us." (32)

In 1913, Louise Rica Jacobs completed a mural, 8ft by 14ft, entitled "The granting of the Commune to the citizens of London by Prince John in 1191" for the first-floor hall of the Commercial Street School, a London Board school. Louise Rica Jacobs was described at the time as a "a Hull artist associated with the Suffrage Atelier, a women’s suffrage group, won the commission in competition." (33) Jacobs also had an exhibition at the Walker Gallery. One newspaper stated she had "craftsmanship of a quite distinguished order, and real charm of style." (34)

Suffrage Propaganda

Ethel Willis, the Honorary Secretary of the Suffrage Atelier urged members to supply the organisation "with hand-printed publications - made from wood blocks, etchings, stencil plates etc.... and by organising Local Meetings for the encouragement of Stencilling, Wood Engraving etc., in order that members may learn or improve themselves in the art of printing by hand." (35)

The Common Cause reported on the work of the Suffrage Atelier: "Weekly cartoon-meetings are held for illustrations, with practical demonstrations of the methods of drawing required for the various processes of pictorial reproduction, so that members may be property qualified to turn out work adapted to reproduction as cartoons, posters, etc. Hand-printing is also practised, so that the society can produce some of its own publications. By this latter process fresh cartoons could be got out at very short notice and very little expense. This could be particularly valuable at election times, when some-thing topical is often needed at once." (36)

It has been argued that the women's suffrage movement were slow to realise the importance of art in the struggle for equal rights. The Vote newspaper later argued: "The value of pictorial art in Suffrage propaganda has not hitherto been sufficiently recognised, until the Suffrage Atelier began its valuable work of educating the public by its pictorial displays, political pictures had scarcely been thought of in the suffrage world." (37)

The Suffrage Atelier listed seventeen ways of forwarding the cause. "These included sending in designs for propaganda, or fine art and craft work for exhibition; helping with secretarial work; selling posters and postcards or getting them placed in the press; contributing to pageants and decorative schemes; collecting funds and obtaining more members; forming local branches (there is no evidence that these existed); contributing cuttings, including photographs, illustrations and cartoons for general reference; providing hospitality in studios or drawing rooms for meetings, exhibitions and social occasions." (38)

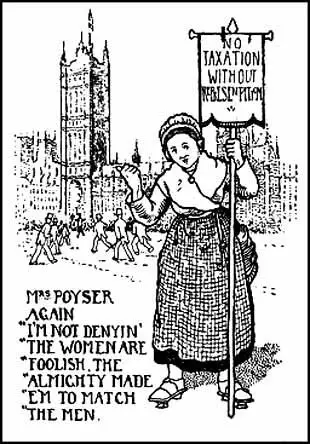

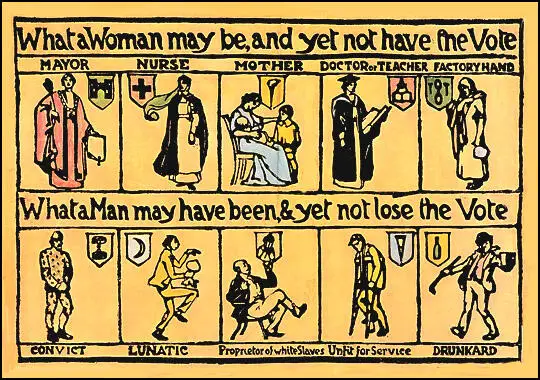

Muriel Matters of the Women's Freedom League was a strong supporter of the Suffrage Atelier organisation. She argued at a meeting in London about the usefulness of pictures as propaganda. "She had found people who were impervious to argument and reason convinced by the postcard representing the lunatic and the lady, or an illustration of Mrs. Poyser's classic remark on men and women." This was a reference to the character Rachel Bede in George Eliot's novel, Adam Bede, published in 1859. (39)

The Suffrage Atelier purchased its own hand-printing press. It formed a "Cartoon Club" that specifically included instructions in hand colour printing and in process-block reproduction. (40) Unlike the Suffrage Atelier it printed its own designs. This included postcards, posters and calenders. (41) Most of the posters and postcards are block prints such as wood or lino-cuts in black and white or hand-coloured. (42) A good example of this is the one below that compares male convicts, lunatics and drunks with the vote with women with responsible jobs who did not have this right. (43)

To encourage new ideas the Suffrage Atelier regularly held competitions. In April 1910 Votes for Women reported that the "Suffrage Atelier has arranged a competition of designs for posters, large and small, and of designs for banners in embroidery and applique. Various prizes are offered." (44)

Educational and Social Centre

The Suffrage Atelier functioned as an educational and social centre with a regular programme of activities that mixed instruction, criticism, designing, printing, banner-making and life drawing with exhibitions and guest speakers. It solicited contributions and offered prizes for successful designs. (45) In doing so it tried to reconcile two aims at the same time: to be of use to suffrage societies in the campaign, but also to afford women artists "opportunities to experiment and... to become acquainted with the processes of reproduction." (46)

The Suffrage Atelier provided art lessons. The organisation arranged for members to draw and paint live models. Votes for Women pointed out: "At these meetings there will be sketching from life (some well-known Suffragists will sit, whenever possible), and all kinds of technical information connected with the society's work will be given." (47) The Suffrage Atelier also provided sessions on public speaking. (48)

Leading members would take it in turns holding "At Home" sessions on the last Thursday in every month. Ethel Willis invited people to her home at 6 Stanlake Villas, Shepherds Bush on several occasions. One journalist was very impressed with one session she attended where Louise Rica Jacobs was showing her work: "The Atelier is run entirely by women artists, who make their own designs, cut blocks and do the printing of posters, postcards, Christmas cards and pictorial leaflets, the uniform of the women being a bright blue workmanlike coat, a black skirt, and a big black bow like that beloved of the artists who dwell near the Luxemburg." (49)

The artist, Dora Meeson Coates, also held "At Home" meetings at her Chelsea Studios. "A large number of Suffragists of all shades gathered to press forward the poster and pictorial campaign which the organisation has so successfully carried on for a considerable time, greatly to the advantage of all other societies, who benefit by this form of advertisement and illustration. Mrs. Fagan, addressing the gathering, made an appeal for money to pay a secretary and a traveller. She felt that the worst sweated labour she knew of was involved in the production of these posters. A traveller was wanted, a woman with charming manners and a determined effort to visit branches of all Suffrage societies, her idea being that every branch of every society should have at least one poster on hoarding near their shop, or even their private address, of meetings, at a cost of £2 per year." (50)

The Suffrage Atelier also organized lectures on a wide-variety of subjects. For example, on 16th March 1910, Dr. Kate Haslam, gave a lecture on "Women in the Medical Profession". (51) The following month she was talking about "English Poor-Law in the 19th Century" at the home of Clemence Housman. (52) In October 1912, the arist, Dora Meeson Coates, a founder member of the Artists' Suffrage League (ASL), arranged "an exhibition of posters and other pictorial work" at her studio. (53)

In December 1911, the Suffrage Atelier held a Christmas party and exhibition of their work at an artist studio in Shepherds Bush that was hosted by Katherine Vulliamy of the Women's Freedom League. "In spite of the wet weather many friends arrived, each bearing a Christmas present, presents which ranged from a mangle to a file – all of great value to the Atelier…. After tea the guests inspected the work shown in the various departments, including original drawings and designs, posters, postcards, and Christmas cards, designed and printed at the Atelier. Mrs Vulliamy of the Women's Freedom League, spoke on the work of the Atelier dwelling chiefly on its value to the Suffrage Societies and to women artists as affording them opportunities to experiment and also to become acquainted with processes of reproduction." (54)

The Suffrage Atelier produced broadsheets which reproduced available designs in miniature so that prospective customers could make their selection. In 1912 their broadsheet offered twenty-nine available designs (almost three times as many as the Artists' Suffrage League produced in the same period. Lisa Tickner argues that "despite their ephemeral nature over forty different posters and about fifty postcards still survive." (55)

Women's Freedom League

Initially most members of the Suffrage Atelier were members of the Women Social & Political Union. However, several members became critical of its arson campaign and left the organisation. Laurence Housman, one of the co-founders of the Suffrage Atelier was especially critical of the WSPU. He was especially upset when Mary Richardson attacked the painting, Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez at the National Gallery. Housman described the "stab in the back given to the Rokeby Venus" as hurting his artistic feelings. "After that came the burning of churches, and I felt myself obliged to cease subscribing to WSPU funds." (56)

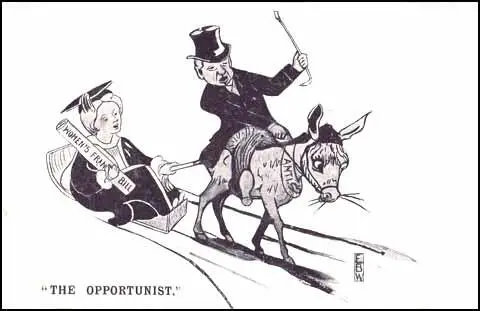

The Suffrage Atelier now became closely associated with the militant but non-violent, Women's Freedom League (WFL) with which it embarked on the joint venture of a "pictorial supplement" with its newspaper, The Vote. (57) In 1912 the WFL worked with the Atelier on a new poster campaign. Charlotte Despard, the leader of the WFL, wrote that their joint campaign would bring the Atelier's work "into more intimate relation" with the movement and the public as a whole, while at the same time illustrating "the advance of the Cause and the fluctuations of the political barometer". (58)

In October 1912, Ethel Willis held a "At Home" at her home at 6 Stanlake Villas, Shepherds Bush where the lithographs of Louise Rica Jacobs, the cartoons of Alfred Pearse, that had appeared in The Vote, and posters produced for the Women's Freedom League were exhibited. Also on display were "Mrs. Ambrose Gosling's beautiful lace and wonderful needlecraft." (59)

Primary Sources

(1) The Common Cause (1st July, 1909)

Weekly cartoon-meetings are held for illustrations, with practical demonstrations of the methods of drawing required for the various processes of pictorial reproduction, so that members may be property qualified to turn out work adapted to reproduction as cartoons, posters etc. Hand-printing is also practised, so that the society can produce some of its own publications. By this latter process fresh cartoons could be got out at very short notice and very little expense. This could be particularly valuable at election times, when some-thing topical is often needed at once. The Society would be glad to send trained workers to take the pictorial and decorative work off the hands of organisers and speakers during elections, when their time and energy are otherwise fully occupied.

(2) Women's Franchise (1st July, 1909)

A somewhat novel suffrage meeting was held by the Suffrage Atelier at the Caxton Hall on Saturday June 26 th , of which the subject was Art and National Movements. Mr Laurence Housman, who presided, showed, in an inspiring address, that art had longed suffered from a lack of connection with life in this country. Pre-Raphaelitism had been an attempt to re-unite art and national life, but the growth of internationalism in technique had not been connected with any international idea or inspiration, such as the Women's Movement now supplied. The pageants of the present day, the revival of old folk-song and dance, and of something resembling a national costume in the purple, green, and white – or green, gold, and white of the Suffrage societies, were signs of the renewal of the blending of art and life.

In the course of some remarks on the importance of symbolism, Mr. Housman noted that when a small war was the subject of cartoons in Punch, England was represented by John Bull, but when a really national crisis intervened the national spirit was symbolised by Britannia, the woman. Our representative house, in its more heroic moods, called itself the "Mother of Parliaments"; at present it resembled rather an absconding father.

Miss Muriel Matters spoke much to the point on the usefulness of pictures as propaganda. She had found people who were impervious to argument and reason convinced by the postcard representing the lunatic and the lady, or an illustration of Mrs. Poyser's classic remark on men and women.

(3) Votes for Women (11th March 1910)

There will be a general meeting of the Suffrage Atelier on March 12th at 3 p.m. at Hampstead. At 4 p.m. Mr Laurence Housman will give an address on "The Aims of the Society". The general meeting is for members only, but any friends or artists interested in the subject are invited to hear the address. Free tickets can be obtained from the Atelier.

Dr. Haslem will give her address on "Women in the Medical Profession" at the Designers' meeting on Wednesday, March 16, at 2.45 p.m.

(4) Votes for Women (1st April 1910)

The Suffrage Atelier has arranged a competition of designs for posters, large and small, and of designs for banners in embroidery and applique. Various prizes are offered. The Design Club will meet in future on Tuesday evenings, from 7 to 9.30, at Edwardes Square. At these meetings there will be sketching from life (some well-known Suffragists will sit, whenever possible), and all kinds of technical information connected with the society's work will be given.

(5) Votes for Women (8th April 1910)

Dr. Kate Haslam will give an address at Edwardes Square, on Wednesday, April 13, at 2.45 p.m.; and also on Wednesday, 20, at the same time. The subject of the first address will be, "The Poor down to the 19th Century"; that of the second, "English Poor-Law in the 19th Century". All interested are invited to attend. Cards of admission may be obtained from the Suffrage Atelier studio, I Pembroke Cottages, Edwardes Square, Kensington.

(6) The Vote (23rd December 1911)

The members of the Suffrage Atelier held a Christmas party and exhibition of their work at the studio, 4, Stanlake Villas, Shepherds Bush, last Wednesday. In spite of the wet weather many friends arrived, each bearing a Christmas present, presents which ranged from a mangle to a file – all of great value to the Atelier…. After tea the guests inspected the work shown in the various departments, including original drawings and designs, posters, postcards, and Christmas cards, designed and printed at the Atelier. Mrs Vulliamy ( Katherine Vulliamy), of the Women's Freedom League, spoke on the work of the Atelier dwelling chiefly on its value to the Suffrage Societies and to women artists as affording them opportunities to experiment and also to become acquainted with processes of reproduction.

(7) The Vote (5th October 1912)

One of the most interesting products of the Women's Suffrage Movement has been the formation of the Suffrage Atelier which has its headquarters at 6 Stanlake Villas, Shepherds Bush. On Thursday, September 26, the Atelier was transformed into an exhibition of pictorial postcards, educational posters, and art needlework of every variety, including a varied show of Suffrage banners…

The Atelier is run entirely by women artists, who make their own designs, cut blocks and do the printing of posters, postcards, Christmas cards and pictorial leaflets, the uniform of the women being a bright blue workmanlike coat, a black skirt, and a big black bow like that beloved of the artists who dwell near the Luxemburg. Miss Willis was a charming hostess, and was admirably supported by Mrs. Tritton, Miss Jacobs, Miss Joseph, Mrs Waller, and other friends….

"At Homes" are being held at the Atelier on the last Thursday in every month, and anyone who wishes to spend a pleasant hour or two could not do better than avail themselves of the invitation to attend.

(8) Votes for Women (11th October 1912)

Suffrage Atelier: Mrs Meeson Coates will be At Home at Glebe Studios, 55 Glebe Place, King's Road, Chelsea, on Tuesday, October 15, from 3.30 p.m. There will be an exhibition of posters and other pictorial work. Mrs Louise Fagan has kindly consented to speak.

(9) The Vote (26th October 1912)

A very pleasant and well-attended function was the "At Home" of the Suffrage Atelier held at the Chelsea Studios by kind invitation of Mrs. Messon Coates. A large number of Suffragists of all shades gathered to press forward the poster and pictorial campaign which the organisation has so successfully carried on for a considerable time, greatly to the advantage of all other societies, who benefit by this form of advertisement and illustration.

Mrs. Fagan, addressing the gathering, made an appeal for money to pay a secretary and a traveller. She felt that the worst sweated labour she knew of was involved in the production of these posters. A traveller was wanted, a woman with charming manners and a determined effort to visit branches of all Suffrage societies, her idea being that every branch of every society should have at least one poster on hoarding near their shop, or even their private address, of meetings, at a cost of £2 per year.

(10) The Vote (9th November 1912)

The monthly "At Home" of the Atelier was held as usual on the last Thursday of the month at its own workshops, 6, Stanlake Villas. On this occasion the members and friends of the Atelier from all the Suffrage societies – were entertained by humourous and other recitations by Miss Elian Hughes, who is about to start a speakers' class in the Atelier on Thursdays on 5.30 p.m. Mrs. Ambrose Gosling's beautiful lace and wonderful needlecraft were displayed upstairs. A one-woman show of clever water-colours and fine lithographs by Miss Louise Jacobs filled another room. Downstairs, Suffrage posters and postcards of the Atelier's own publication were on sale and on view, many of these being cartoons for the Vote and posters for the Caxton Hall meetings and the International Suffrage Fair at Chelsea Town Hall. The Atelier decorated the Caxton Hall at the Women's Freedom League Reception to the International Delegates on October 28, and exhibited posters which proved very attractive.

(11) Philip V. Allingham, Alfred Pearse: Cartoonist, Illustrator and Advocate of Women's Rights (7th July, 2015)

English cartoonist, illustrator, and vigorous campaigner for women's equality, Alfred Pearse (1855–1933), who also signed himself as "A Patriot," was a fourth generation artist and son of celebrated decorative artist J. S. Pearse. Formally trained, he attended the West London School of Art, winning many prizes for his drawing. At the turn of the century, Alfred Pearse, now an established artist, was also regularly published in The Illustrated London News, the Boy's Own Paper, and the illustrated magazine of London humour Punch. Besides designing campaign posters advocating women's suffrage, Pearse composed a weekly cartoon for Votes for Women from 1909, and, with Laurence Housman, set up the Suffrage Atelier. In the next decade, Pearse produced various artworks, cartoons, and propaganda supporting British and her allies in World War One. He was not merely a competent wood engraver and solid book illustrator; he also acted as art critic for the Manchester Guardian.

(12) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987)

Women were able to organise collectively and contribute their professional skills to the suffrage campaign. They designed, printed and embroidered all manner of political material; they taught each other the requisite skills from hand-painting to needlework; they designed major demonstrations and took part in them in their own contingents; they lent their studios for meetings and contributed to exhibitions, bazaars and fund-raising activities...

They saw themselves as aiding the women's movement by a whole variety of means. An early note from Miss E. B. Willis, the Honorary Secretary, lists seventeen ways of forwarding the cause. These included sending in designs for propaganda, or fine art and craft work for exhibition; helping with secretarial work; selling posters and postcards or getting them placed in the press; contributing to pageants and decorative schemes; collecting funds and obtaining more members; forming local branches (there is no evidence that these existed); contributing cuttings, including photographs, illustrations and cartoons for general reference; providing hospitality in studios or drawing rooms for meetings, exhibitions and social occasions.

(13) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000)

Catherine Courtauld (later Mrs Dowman), sister of Samuel and Renee Courtauld, was a member of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage in 1906 and later became a member of the Suffrage Atelier. Several of her designs, such as The Anti-Suffrage Ostrich (c. 1909), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Portrait Painter (c. 1912), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Prophet (c. 1912), The Anti-Suffrage Society as Dressmaker (c.1912), The Prehistoric Argument (1912), and Waiting for the Living Wage (c. 1913) were produced as postcards.

(14) Claire Voon, British Suffrage Movement Posters Goes on Display (26th February, 2018)

The visual language, too, was diverse. Some posters were satirical, drawing from familiar 19th-century political caricatures, while others featured more evocative, emotional images. One poster by cartoonist Alfred Pearse (signed "A. Patriot") depicts the force-feeding of an imprisoned suffragette on a hunger strike - a practice that the government authorized in 1909.

The colorful pictures represented the voices of professional artists as well as everyday citizens - both women and men. Many of them are signed. The most famous among these creatives, arguably, is the painter Duncan Grant, who was a member of the modernist Bloomsbury Group. Others include Mary Sargant Florence, a mural painter, and Emily Jane Harding Andrews, a book illustrator. Harding Andrews created posters for the Artists' Suffrage League, one of two chief organizations in Britain that were responsible for producing poster and postcard designs. The League was established in 1907 by stained-glass artist Mary Lowndes, two years prior to the founding of the collective known as Suffrage Atelier. Formed specifically to gear up for a demonstration by the Women's Social and Political Union - the society set up by suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst - Suffrage Atelier favored using woodblocks to more quickly produce and distribute their posters.

For Britons, the century-old notices vividly capture the voices of overlooked individuals who fought for greater gender equality in their nation. For the rest of us, they're poignant reminders of the significant role grassroots movements play in enacting systemic change.

Student Activities

References

(1) Diane Atkinson, Funny Girls: Cartooning for Equality (1997) page 44

(2) Constitution of the Suffrage Atelier (8th May 1909)

(3) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 16

(4) Diane Atkinson, Funny Girls: Cartooning for Equality (1997) page 74

(5) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 63

(6) David Simkin, Family History Research (30th December, 2022)

(7) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 143

(8) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 244

(9) Philip V. Allingham, Alfred Pearse: Cartoonist, Illustrator and Advocate of Women's Rights (7th July, 2015)

(10) Claire Voon, British Suffrage Movement Posters Goes on Display (26th February, 2018)

(11) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 27

(12) Philip V. Allingham, Alfred Pearse: Cartoonist, Illustrator and Advocate of Women's Rights (7th July, 2015)

(13) Laurence Housman, The Unexpected Years (1937) page 274

(14) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 125

(15) Elizabeth Crawford, Clemence Housman: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September, 2004)

(16) Katharine Cockin, Laurence Housman : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(17) Laurence Housman, The Unexpected Years (1937) pages 263, 274, 277

(18) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 406

(19) Women's Franchise (1st July, 1909)

(20) Alfred Sutro, Celebrities and Simple Souls (1933) page 131

(21) Arnold Bax, Farewell My Youth and Other Writings (1992) page 35

(22) Laurence Housman, letter to Janet Ashbee (14th June, 1908)

(23) Votes for Women (25th June, 1908)

(24) Ian McDonald, Vindication: A Postcard History of the Women's Movement (1989) page 55

(25) Elizabeth Oakley, Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence and Laurence Housman (2009) page 76

(26) Mary Lowndes, On Banners and Banner-Making (1909)

(27) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 126

(28) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 130

(29) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 131

(30) Louise Rica Jacobs, The Vote (28th December 1912)

(31) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 131

(32) Women's Freedom League Annual Report (1911) pages 19-22

(33) The Shoreditch Observer (13th December, 1913)

(34) The Westminster Gazette (10th March 1914)

(35) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 21

(36) The Common Cause (1st July, 1909)

(37) The Vote (15th June, 1912)

(38) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) pages 20-21

(39) Women's Franchise (1st July, 1909)

(40) Women's Franchise (8th July 1909)

(41) The Common Cause (27th October 1910)

(42) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 21

(43) Diane Atkinson, Funny Girls: Cartooning for Equality (1997) page 17

(44) Votes for Women (1st April 1910)

(45) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 21

(46) The Vote (23rd December 1911)

(47) Votes for Women (1st April 1910)

(48) The Vote (9th November 1912)

(49) The Vote (5th October 1912)

(50) The Vote (26th October 1912)

(51) Votes for Women (11th March 1910)

(52) Votes for Women (8th April 1910)

(53) Votes for Women (11th October 1912)

(54) The Vote (23rd December 1911)

(55) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 21

(56) Laurence Housman, The Unexpected Years (1937) page 141

(57) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987) page 25

(58) The Vote (23rd December 1911)

(59) The Vote (9th November 1912)