Men's League for Women's Suffrage

Although the majority of men opposed the idea of women voting in parliamentary elections, some leading male politicians supported universal suffrage. This included severals leading figures of the Labour Party, including James Keir Hardie, George Lansbury, Harold Laski, Gerald Gould and Philip Snowden. Another Labour politician, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, helped to fund Votes for Women newspaper and provided bail for nearly a thousand members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who were arrested for breaking the law.

Robert Cecil, one of the main figures in the Conservative Party was also a supporter but most were totally opposed to the idea of votes for women. Several members of the Liberal administration, such as David Lloyd George, also favoured women being granted the vote.

In 1907, several left-wing intellectuals, including Henry Nevinson, Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Henry Harben, Gerald Gould, Charles Mansell-Moullin, and 32 other men formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men."

At a by-election in Wimbledon in 1907 Bertrand Russell, stood as the Suffragist candidate. Evelyn Sharp later argued: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Lansbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

In 1909 the Men's League for Women's Suffrage published a list of prominent men in favour of women's suffrage. This included 83 former government ministers, 49 church leaders, 24 high-ranking army and navy officers, 86 academics and the writers E. M. Forster, Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells, John Masefield and Arthur Pinero. By 1910 it had ten branches in Britain.

The Men's League for Women's Suffrage had no political party affiliation, was non-militant in its methods, but supported both the Women Social & Political Union and Women's Freedom League. The MLWS concentrated on "propagandist work". Charles Mansell-Moullin was one of the most active of the members. In a letter that he had published in The Daily Mirror on 22nd November 1910, he complained about how the police were treating members of the WSPU during demonstrations: "The women were treated with the greatest brutality. They were pushed about in all directions and thrown down by the police. Their arms were twisted until they were almost broken. Their thumbs were forcibly bent back, and they were tortured in other nameless ways that made one feel sick at the sight... These things were done by the police. There were in addition organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputation like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police; but they contented themselves with throwing the women down and trampling upon them."

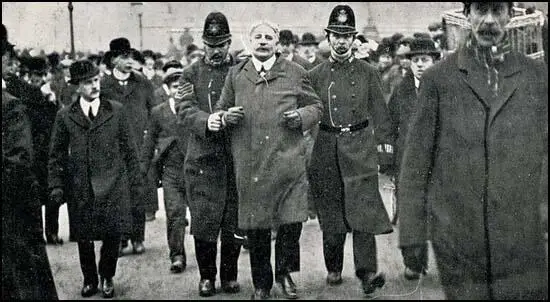

Men's League for Women's Suffrage (18th November, 1910)

In October, 1912, George Lansbury decided to draw attention to the plight of WSPU prisoners by resigning his seat in the House of Commons and fighting a by-election in favour of votes for women. Lansbury discovered that a large number of males were still opposed to equal rights for women and he was defeated by 731 votes. The following year he was imprisoned for making speeches in favour of suffragettes who were involved in illegal activities. While in Pentonville he went on hunger strike and was eventually released under the Cat and Mouse Act.

C. E. M. Joad was another member of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage: "I joined the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement, hobnobbed with emancipated feminists who smoked cigarettes on principle, drank Russian tea and talked with an assured and deliberate frankness of sex and of their own sex experiences, and won my spurs for the movement by breaking windows in Oxford Street for which I spent one night in custody."

Evelyn Sharp later commented: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Lansbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

several postcards like the one above in support of

the women's suffrage movement. The postcard refers

to the Married Women's Property Act.

Dr. Charles Mansell-Moullin joined forces with Sir Victor Horsley and Dr. Agnes Savill to write a report on the impact of the forced-feeding of suffragettes. In a speech on 13th March, 1913 he argued that Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, had been making misleading statements to the House of Commons: "Now Mr. McKenna has said time after time that forcible feeding, as carried out in His Majesty's prisons, is neither dangerous nor painful. Only the other day he said, in answer to an obviously inspired question as to the possibility of a lady suffering injury from the treatment she received in prison, "I must wait until a case arises in which any person has suffered any injury from her treatment in prison."... He relies entirely upon reports that are made to him - reports that must come from the prison officials, and go through the Home Office to him, and his statements are entirely founded upon those reports. I have no hesitation in saying that these reports, if they justify the statements that Mr. McKenna has made, are absolutely untrue. They not only deceive the public, but from the persistence with which they are got up in the same sense, they must be intended to deceive the public."

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Fate Has Been Kind (1943)

That autumn (1906) saw, the beginning of the Monday afternoon 'At Homes', which went on continuously year in year out during the militant campaign. They were intended principally for women, but men were not excluded. Strategy was explained, militant demonstrations were announced, a collection was taken and members were enrolled. I generally came and sold literature - books, pamphlets and, later, the Votes for Women newspaper. When the attendance grew too big to be accounted in the office in Clement's Inn the venue was changed to the Portman Rooms in Baker Street, and later to the Queen's Hall.

At the end of October 1906 events occured which brought me into far closer association with the movement. My wife was arrested. She had gone, with other members of the Women's Social and Political Union to the House of Commons on the day that Parliament opened; and in accordance with a preconcerted plan she had jumped up on to one of the seats in the Central Lobby and started to address the M.P.s and others who were present. Pulled down and bundled out into the street, along with a number of other women who had made a similar protest, she had tried to re-enter the House and had been taken into custody.

I went with her to the Court next morning, and she surrendered to her bail, together with nine other women, including Mrs. Cobden Sanderson, daughter of Richard Cobden. The magistrate bound them all over to enter into their own recognizances to keep the peace for six months. This they unanimously refused to do. In default, they were committed to prison for two months. They were accordingly packed off the Holloway.

I determined at once that during my wife's absence her side of the work should not suffer. I agreed to look after the finances, and at a public meeting that very afternoon I made an appeal for funds. By way of setting the ball rolling I promised to contribute £10 for every day of her imprisonment.

(2) C. E. M. Joad, Under the Fifth Rib (1932)

Looking back, I can date the change from a meal which I had with Mr. H. D. Harben in the autumn of 1914 and the homily which it provoked. H. D. Harben was a Socialist; he was rich, he was a gentleman, and he had a large place in the country. He was also an ardent suffragist. Suffragettes, let out of prison under the "Cat and Mouse Act", used to go to Newlands to recuperate, before returning to prison for a fresh bout of torture. When the county called, as the county still did, it was embarrassed to find haggard-looking young women in dressing-gowns and djibbahs reclining on sofas in the Newlands drawing-room talking unashamedly about their prison experiences. This social clash of county and criminals at Newlands was an early example of the mixing of different social strata which the war was soon to make a familiar event in national life. At that time it was considered startling enough, and it required all the tact of Harben and his socially very competent wife to oil the wheels of tea-table intercourse, and to fill the embarrassed pauses which punctuated any attempt at conversation.

(3) Charles Mansell-Moullin, The Daily Mirror (22nd November, 1910)

I notice in your account of the reception given to the deputation from the W.S.P.U. to the Prime Minister on Friday last it is stated that the police behaved with great good temper, tact, and restraint.

This may have been the case on previous occasions on which deputations have been sent; on the present one it is absolutely untrue.

The women were treated with the greatest brutality. They were pushed about in all directions and thrown down by the police. Their arms were twisted until they were almost broken. Their thumbs were forcibly bent back, and they were tortured in other nameless ways that made one feel sick at the sight.

I was there myself and saw many of these things done. The photographs that were published in your issue of November 19 prove it. And I have since seen the fearful bruises, showing the marks of the fingers, caused by the violence with which these women were treated.

These things were done by the police. There were in addition organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputation like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police; but they contented themselves with throwing the women down and trampling upon them.

As this behaviour on the part of the police is an entirely new departure, it would be interesting to know who issued the instructions that they were to act with such brutality, and who organised the bands of roughs who suddenly sprang up on all sides from nowhere.

The Home Secretary, who does not want women arrested, is credited with the statement that he had devised a new method of putting a stop to deputations. Is this the method?

The women were discharged without a trial by the Secretary of State on the grounds of public policy. Is it public policy that there should be no trial and that the evidence which might otherwise have some out should be suppressed in this way?

(4) Evelyn Sharp believed that the role played by the Men's League for Women's Suffrage was very important in the struggle for the vote.

It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Lansbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war.

(5) Rev. Rupert Strong, speech at Hammerwood Park (27th January, 1913)

The movement for women's suffrage was one of vital importance to the morality and welfare of the nation. I believe women should have some share in the government in order to promote clean living.

(6) The East Grinstead Observer (8th March, 1913)

An East Grinstead branch of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage was formed last Thursday. Rev. G. B. Riddell, presided and the Rev. Rupert Strong was elected chairman. Mr. R. J. Callaway as treasurer and Mr. E. T. Godwin as secretary. Letters were read expressing sympathy for the movement from Lord Robert Cecil and Mr. Charles Corbett.

(7) The East Grinstead Observer (15th March, 1913)

A meeting of the Central Sussex Suffrage Society was held at the Congregational Hall, Horsted Keynes. Rev. J. L. Brack, rector of Ardingly, expressed dislike of militant methods and added that this was an additional reason for supporting the work of those suffragists who had carefully avoided the use of physical force. He based his sympathy with the women's suffrage movement partly upon his experience as a chaplain to a workhouse, where the only visitor who understood how things went on was a lady Guardian. Mrs. Marie Corbett and Miss A. S. Verrall thanked the speakers.

(8) The East Grinstead Observer (8th March, 1913)

At a meeting of the East Grinstead branch of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage on Tuesday evening, the Rev. G. B. Riddell condemned the tactics of the militant suffragettes and said he did not blame men for their brutality and the lynch law of the crowd.

(9) C. E. M. Joad, Under the Fifth Rib (1932)

As my views in general were derived from books rather than from life, so in particular and inevitably were my views of women. I conceived myself to have learnt from my reading that women were the equals of men, denied their proper place in society by the same selfishness embodied in vested interests as impeded the realization of Socialism. Those were the days of the agitation for women's suffrage, which was culminating in attacks upon property and the harassing of eminent persons.

I joined the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement, hobnobbed with emancipated feminists who smoked cigarettes on principle, drank Russian tea and talked with an assured and deliberate frankness of sex and of their own sex experiences, and won my spurs for the movement by breaking windows in Oxford Street for which I spent one night in custody. But perhaps the most vivid memory of these feminist experiences is that of courting surreptitiously the daughter of an Oxford landlady, prevailing upon her, after immense difficulty, to come with me to Brighton for the week-end, planning the necessary arrangements with the most elaborate secrecy, concocting an ingenious alibi to enable her to explain her

absence to her mother, and then finding the mother at the railway station to see me off, where I duly received her blessing for my enterprise in assisting to emancipate women from the shackles of convention.

I only mention this simple-minded advocacy of feminism as an extreme example of the academic rationalism which in these days characterized my opinions. I had had, it should be noted, practically no experience of women; I did not in the least know what women were like. But my reason, countenanced and encouraged by Shaw, told me that their difference from men was limited to a difference in function touching the procreation of children, a difference which, I was assured, was not relevant to the performance of functions appertaining to the other departments of life. Politically, socially and intellectually women were the equals of men; this equality should, I thought, inform personal relations and receive explicit recognition from society. My reason, supported by Shaw, further assured me that there was no reason why I should abstain from sexual intercourse with a woman merely because we had not been through a preliminary ceremony in the shrine of an obsolete religion where an incantation had been pronounced over us by a priest.

(10) Charles Mansell-Moullin, speech at Kingway Hall (18th March, 1913)

Last summer there were 102 Suffragettes in prison; 90 of those were being forcibly fed. All sorts of reports were being spread about what was being done to them. We got up a petition to the Home Secretary, we wrote him letters, we interviewed him so far as we could. We got absolutely no information of any kind that was satisfactory; nothing but evasion. So three of us formed ourselves into a committee - Sir Victor Horsley, Dr. Agnes Savill, and myself, and we determined that we would investigate these cases as thoroughly as we could. I don't want to be conceited, but we had the idea that we had sufficient experience in public and hospital practice and in private practice to be able to examine those persons, to take their evidence, to weigh it fully, and to consider it. And we drew up a report, and that report was published in The Lancet and in the British Medical, at the end of August last year.

We stand by that report. There is not a single thing in that report that we wish to withdraw. There are some few things that we might put more strongly now than we did then. Everything that has happened since has merely strengthened what we said, and has confirmed what we predicted would happen.

Now Mr. McKenna has said time after time that forcible feeding, as carried out in His Majesty's prisons, is neither dangerous nor painful. Only the other day he said, in answer to an obviously inspired question as to the possibility of a lady suffering injury from the treatment she received in prison, "I must wait until a case arises in which any person has suffered any injury from her treatment in prison." I got those words from The Times - of course, they may not be correctly reported. Well, of course, Mr. McKenna has no personal knowledge. Mr. McKenna has never, as far as I know, made any enquiry for himself, nor do I think if he did it would have had any effect one way or the other. He relies entirely upon reports that are made to him - reports that must come from the prison officials, and go through the Home Office to him, and his statements are entirely founded upon those reports. I have no hesitation in saying that these reports, if they justify the statements that Mr. McKenna has made, are absolutely untrue. They not only deceive the public, but from the persistence with which they are got up in the same sense, they must be intended to deceive the public.

I don't wish to exonerate Mr. McKenna in the least. He has had abundant opportunity - in fact, it has been forced upon his notice - of ascertaining the falsehood of these statements, and if he goes on repeating them after having been told time after time by all sorts of people that they are not correct, he makes himself responsible for them whether they are true or not. And in his own statements in the House of Commons he has given sufficient evidence of his frame of mind with regard to this subject. Time after time has he told the Members of the House that there was no pain or injury, and almost in the same breath - certainly in the same evening - he has told how one of these prisoners has had to be turned out at a moment's notice, carried away in some vehicle or other, and attended by a prison doctor, to save her life. One or other of these statements must be absolutely untrue.

Now I come to the question of pain. Mr. McKenna says that there is none. Let me read you an account of how they manage. Of course, the prison cells are ranged down either side of a corridor. All the doors are opened when this business is going to begin, so that nothing may be lost. "From 4:30 until 8:30 I heard the most dreadful screams and yells coming from the cells." This is the statement of a prisoner whom I know and who I know does not exaggerate: "I had never heard human beings being tortured before... I sat on my chair with my fingers in my ears for the greater part of that endless four hours. My heart was thumping against my ribs, as I sat listening to the procession of the doctors and wardresses as they came to and fro, and passed from cell to cell, and the groans and cries of those who were being fed, until at last the procession paused at my door. My turn had come."

That is a statement. I hope none of you has ever been so unfortunate as to be compelled to listen to the screams of a person when you are yourself in perfect health - the screams of a person in agony, screams gradually getting worse and worse, and then, at last, when the person's strength is becoming exhausted, dying down and ending in a groan. That is bad enough when you are strong and well, but if you come to think that these prisoners hear those screams in prison, that they are the screams of their friends, that they are helpless, that they know those screams are being caused by pain inflicted without the slightest necessity - I am not exaggerating in the least, I am giving you a plain statement of what goes on in His Majesty's prisons at the present time - then it becomes a matter upon which it is exceedingly difficult to speak temperately.

Then they say there is no danger. In one instance - that of an unresisting prisoner in Winson Gaol, Birmingham - there is no question but that the food was driven down into the lungs. The operation was

stopped by severe choking and persistent coughing. All night the prisoner could not sleep or lie down on account of great pain in her chest. She was hastily released next day, so ill that the authorities when discharging her obliged her to sign a statement that she left the prison at her own risk. On reaching home she was found to be suffering from pneumonia and pleurisy, caused from fluid being poured into her lungs. The same thing happened only the other day in the case of Miss Lenton. Fortunately, she is steadily recovering, and the Home Secretary may congratulate himself that these two cases - there have been others - are recovering, and that there will not have to be an inquest.

Then with regard to Miss Lenton. The Home Secretary wrote that she was reported by the medical officer of Holloway Prison to be in a state of collapse, and in imminent danger of death consequent upon her refusal to take food. This statement is not true. "Three courses were open - to leave her to die; to attempt to feed her forcibly, which the medical officer advised would probably entail death; and to release her on her undertaking to surrender herself at the further hearing of her case." That implied that she was not forcibly fed. She had been, but that fact was suppressed - suppressed by the Home Secretary in the statement he published in the newspapers, suppressed because the cause of her illness was forcible feeding. That has been proved absolutely.

As regards the moral and mental deterioration that has been already alluded to by Mr. Forbes Robertson and Mr. Bernard Shaw, I will only say this one thing. It shows itself everywhere where forcible feeding is practised. It shows itself in the prisons, where the medical officers, I am sorry to say, have on more than one occasion laughed and made stupid jokes about "stuffing turkeys at Christmas." It shows itself in the prison officials, in the reports they have drawn up. It shows itself in the Home Secretary in the untrue statements that he has published and the evasions that he has made; and it shows itself, too, in the ribald laughter and obscene jokes with which the so-called gentlemen of the House of Commons received the accounts of these tortures.