Israel Zangwill

Israel Zangwill was born in Whitechapel on 21st January, 1864. He was the second of the five children of Moses Zangwill, an itinerant pedlar, glazier, and rabbinical student, and his wife, Ellen Hannah Marks, a Polish Jewish immigrant.

He attended the Jews' Free School in Spitalfields. After receiving his degree at the University of London he returned to his school as a teacher. In June 1888 he resigned from his teaching position to become a journalist on the staff of the newly founded weekly newspaper the Jewish Standard.

His first novel, The Bachelors' Club, was published in 1891. His short-stories appeared in various magazines including The Idler, a magazine edited by his friend from university, Jerome K. Jerome. He was also editor of The Puck Magazine, a comic journal which folded in February 1892. The publication of Children of the Ghetto (1892), according to one critic, "with its powerful realistic depiction of ghetto life, established Zangwill as a spokesperson for Jewry within and outside the Jewish world." This was followed by Ghetto Tragedies (1893), The King of Schnorrers: Grotesques and Fantasies (1894) and Dreamers of the Ghetto (1898).

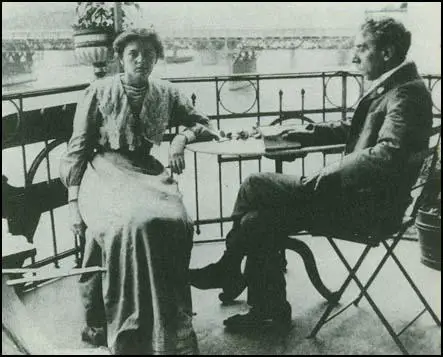

In 1903 Zangwill married Edith Ayrton, the daughter of the physicist William Edward Ayrton and stepdaughter of Ayrton's second wife, Hertha Ayrton. Edith's mother, Matilda Chaplin Ayrton (1846-1883), had been a doctor and a member of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage. Edith was brought up by Hertha, who was Jewish.

With her husband's encouragement Edith published a novel, Barbarous Babe in 1904. This was followed by The First Mrs Mollivar (1905). Edith shared her stepmother's support for women's suffrage and became a member of the NUWSS. The couple had three children: George (born 1906), who became an engineer and worked in Mexico; Margaret (1910), who suffered from a mental condition and was institutionalized and Oliver (1913), who became professor of experimental psychology at the University of Cambridge.

Frustrated by the lack of progress in achieving the vote Edith Zangwill and Hertha Ayrton accepted that a more militant approach was needed and in 1907 they joined the Women Social & Political Union. In a letter she wrote to Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Hertha admitted: "I made up my mind some time ago that as I am unable to be militant myself, from reasons of health, and as I believe most fully in the necessity for militancy, I was bound to give every penny I can afford to the militant union that is bearing the brunt of the battle, namely the WSPU."

On 9th February 1907, Zangwill shared a platform with Keir Hardie on the subject of women's suffrage. Sylvia Pankhurst recorded: "When Mr. Zangwill came to speak, he.... declared himself to be a supporter of the militant tactics and the anti-Government policy, and the same Liberal ladies (who had hissed Keir Hardie), although they had themselves asked him to speak for them, expressed their dissent and disapproval as audibly as though they had been Suffragettes and he a Cabinet Minister."

Zangwill was criticised for supporting the militant tactics of the Women Social & Political Union. To the charge that members were "unwomanly" he replied that "ladylike means are all very well if you are dealing with gentlemen; but you are dealing with politicians". He added that "for every government - Liberal or Conservative - that refuses to grant female suffrage is ipso facto the enemy."

In 1907, several left-wing intellectuals, including Israel Zangwill, Henry Nevinson, Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Hugh Franklin, Charles Mansell-Moullin, Herbert Jacobs, and 32 other men formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." Evelyn Sharp later argued: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Landsbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

In November 1912 Israel Zangwill and Edith Zangwill helped form the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage. The main objective was "to demand the Parliamentary Franchise for women, on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." One member wrote that "it was felt by a great number that a Jewish League should be formed to unite Jewish Suffragists of all shades of opinions, and that many would join a Jewish League where, otherwise, they would hesitate to join a purely political society." Other members included Henrietta Franklin, Hugh Franklin, Lily Montagu and Inez Bensusan.

In November 1913, Zangwill wrote an article for The English Review where he rejected militancy for its own sake as dramatic but not politically effective, and criticised the increased lack of democracy in the Women Social & Political Union. Zangwill especially disapproved of the arson campaign of the WSPU and in February 1914 helped to establish the non-militant United Suffragists.

Zangwill was a strong supporter of Zionism. His biographer, Joseph H. Udelson, the author of Dreamer of the Ghetto: the Life and Works of Israel Zangwill (1990) has argued "From 1901 to 1905 (Zangwill) was an advocate of official Herzlian Zionism; from 1905 to 1914 he was the driving force behind insurgent Territorialism; and from 1914 to 1919 he was the leading Western advocate of a Palestine-centred Jewish nationalism". On 16th January, 1920 The Times published a letter from Zangwill: "What is now being concocted in Paris (that is, a League of Nations mandate) is a scheme without attraction save for mere refugees, a scheme under which a free-born Jew returning to Palestine would find himself under British military rule, aggravated by an Arab majority in civic affairs." Alfred Sutro observed that: "under a somewhat truculent exterior he was curiously unselfish and tender-hearted… A fiery spirit, a man who all his life followed a great idea."

Another biographer, William Baker, has argued: "Zangwill was angular, tall, gaunt, and bespectacled, and was a witty, powerful and epigrammatic speaker who attracted large audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition to his novels he translated the Hebrew liturgy into English and wrote poetry and twenty dramas - many of which were adaptations from his novels."

Suffering from poor health he retired to his home at Far End, East Preston. His biographer, Joseph Udelson, the author of Dreamer of the Ghetto (1990), has pointed out: " Zangwill's physical and mental health deteriorated seriously during the following two months as the incessant insomnia and anxiety acted upon his always fragile physical constitution. No longer capable of doing any work, he was confined to his home."

Israel Zangwill died of pneumonia on 1st August 1926 at Oakhurst, a nursing home in Midhurst, West Sussex.

Primary Sources

(1) Joseph Udelson, Dreamer of the Ghetto (1990)

With publication of Children of the Ghetto, Israel Zangwill became the most prominent English-language Jewish novelist on both sides of the Atlantic. In it he had implemented fully Amy Levy's program of portraying the Western Jewish milieu in literature. In this effort he was following consciously in the tradition of the Western "ghetto" authors.

But enlarging upon this agenda, Zangwill sought not merely to describe but through his realistic depiction of the "private" world of the immigrants also to attack the negative literary stereotype of the Jew and to evoke a more human and sympathetic image of the Jews in Western society. In 1892 this was still a most daring venture requiring great courage, for it entailed the risks of offending "polite" British opinion and image-conscious Jewish spokesmen. That he succeeded is evident from the work's immediate reception.

Children of the Ghetto won critical acclaim among both non-Jewish and Jewish reviewers. They recognized that Israel Zangwill, with this book, had entered upon a new stage in his literary career, one to be taken much more seriously than his New Humour phase.

(2) The Athenaeum (5th November, 1892)

In "Children of the Ghetto" he strikes out a new line... the present book is a serious novel of considerable merit.... The chief interest of the book lies in the wonderful description of the Whitechapel Jews.... The picture is most sympathetically drawn.... But his sympathy does not blind him to their faults.... Moreover the vividness and force with which Mr. Zangwill brings before us the strange and uncouth characters with which he had peopled his book are truly admirable.

(3) The Jewish Chronicle (14th October, 1892)

Admirable for wit and originality as Mr. Zangwill's earlier books have been, in the "Children of the Ghetto" he strikes a firmer and more ambitious note. Here he must be judged as a novelist, as a writer who seeks to portray human life, while before he was the narrator of confessedly bizarre impossibilities. And the result of a close study of Mr. Zangwill's new book is to convince the reader ... that in Mr. Zangwill a literary star of the first magnitude has at last risen above the Jewish horizon in England....

That the "Children of the Ghetto" is very largely true is clear to the superficial reader, and clearer still to the careful reader. Mr. Zangwill has a mastery over Jewish custom, over Jewish life in all its crannies and ramifications, he has insight into the ideal and an eye for the mean and tawdry, a sigh for its pathos and a smile for its joy like Franzos.

(4) Evelyn Sharp believed that the role played by the Men's League for Women's Suffrage was very important in the struggle for the vote.

It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Landsbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war.

(5) In his diary, Arnold Bennett described the first meeting of the War Propaganda Bureau at Wellington House on 2nd September, 1914.

Masterman in the chair. Zangwill talked a great deal too much. The sense was talked by Wells and Chesterton. Rather disappointed in Gilbert Murray, but I like the look of little R. H. Benson. Masterman directed pretty well, and Claude Schuster and the Foreign Office representative were not bad. Thomas Hardy was all right.

(6) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

I was determined to join the Pankhursts' organisation, the Women's Social and Political Union, but was held up in this resolve for three months by the fact that my father, who had considerable foresight and realised pretty well what joining that body was likely to mean, was inclined to be opposed to the idea. However, I finally decided that he could be no judge of a matter which concerned one primarily as a woman. Prid meanwhile had, travelling by a slightly different road, arrived at the same conclusion. She and I met one autumn day in London, and, full of excitement, went off together to Clement's Inn and joined.

One of the first effects that joining the militant movement had on me, as perhaps on the majority of those of my generation who went into it, was that it forced me to educate myself. I read to begin with, of course, the whole literature of feminism: leaflets, pamphlets, books in favour and books against. Of books that mattered dealing directly with feminism there were curiously few. Only three now stay in my mind: John Stuart Mill's " Subjection of Women," Olive Schreiner's " Woman and Labour," Cicely Hamilton's "Marriage as a Trade"; and perhaps one should add a fourth, Shaw's " Quintessence of Ibsenism." Of course, there were stray passages in others; one or two of Israel Zangwill's Essays, for example, I find unforgettable to this day.

Of the quantities of books on politics, economics, finance, the working of the Exchanges, sociology, anthropology and psychology which I read during the first few happy years of that new revelation, some few still remain fresh in my mind. I can still, for example, vividly remember reading Havelock Ellis's " Psychology of Sex." It was the first thing of its kind I had found. Though I was far from accepting it all, it opened up a whole new world of thought to me. I discussed it at some length with my father, and he, much interested, went off to buy the set of volumes for himself; but in those days one could not walk into a shop and buy "The Psychology of Sex "; one had to produce some kind of signed certificate from a doctor or lawyer to the effect that one was a suitable person to read it. To his surprise he could not at first obtain it. I still remember his amused indignation that he was refused a book which his own daughter had already read. But the fact was that the Cavendish Bentinck Library, to which I, in common with many others, owe a deep debt of gratitude, was at that time supplying all the young women in the suffrage movement with the books they could not procure in the ordinary way.

(7) Joseph Udelson, Dreamer of the Ghetto (1990)

Zangwill's physical and mental health deteriorated seriously during the following two months as the incessant insomnia and anxiety acted upon his always fragile physical constitution. No longer capable of doing any work, he was confined to his home. And at the beginning of July, Edith Zangwill admitted to a friend who was intending to come down to Far End for a visit, "My husband has had a serious nervous breakdown, and is in a nursing home."

On 1 August 1926 Israel Zangwill unexpectedly died at the nursing home in Midhurst, Sussex; he was sixty-two years old. The funeral, at which the rabbi of London's Liberal Jewish Synagogue, St. John's Wood, officiated, was held on 5 August at the Golders Green Crematorium; Stephen S. Wise, visiting from the United States, delivered the eulogy.