Ethel Rosenberg

Ethel Greenglass was born at 64 Sheriff Street on the lower East Side of New York City on 28th September, 1915. She attended the Seward Park High School with her brother, David Greenglass. After taking a short secretarial course, she held a variety of clerical jobs and became an active trade unionist. She lived with her family , turning over her entire salary to them "except for carfare and lunches". (1)

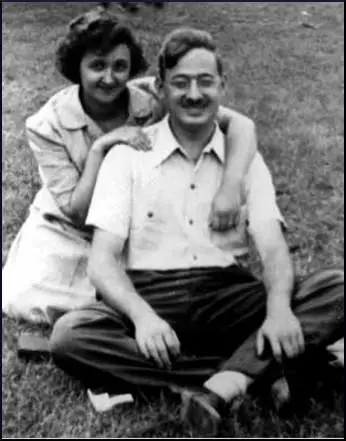

In 1939 Ethel married Julius Rosenberg. After a year of doing odd jobs, in 1940, he was employed by the Army Signal Corps as a junior engineer. In 1941 he was recruited by Jacob Golos as a Soviet spy. However, he was later transferred by Vassily Zarubin to Semyon Semyonov. As Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) has pointed out that "because Golos had virtually no scientific or technical knowledge, though he was controlling dozens of sources providing information in these fields, it is difficult for him to supervise Rosenberg's group." (2)

The couple lived in Knickerbocker Village. One visitor later recalled: "The Rosenbergs lived in lower Manhattan, near the Brooklyn Bridge, at 10 Monroe Street, in a large low-rent project called Knickerbocker Village. They lived in a modest three-room apartment on the 8th floor of Building G, a dark brick ten-story tower... There was a sort of walkway held up by a metal structure connecting the sidewalk to the entrance... The electric lock buzzed and the door opened. I was in a clean, well-swept hallway in spite of the modest appearance of the building." (3)

According to Walter Schneir and Miriam Schneir, the authors of Invitation to an Inquest (1983): "To help her raise her children she had taken courses in child psychology at the New School for Social Research... In her Knickerbocker Village apartment, she had performed al the chores of a housewife and mother, hiring help only briefly after the birth of each child and, in 1944-45, during a period of ill health." (4)

In September 1944, Julius Rosenberg suggested to Alexander Feklissov that he should consider recruiting his brother-in-law, David Greenglass and his wife, Ruth Greenglass. Feklissov met the couple and on 21st September, he reported to Moscow: "They are young, intelligent, capable, and politically developed people, strongly believing in the cause of communism and wishing to do their best to help our country as much as possible. They are undoubtedly devoted to us (the Soviet Union)." (5)

Ethel Rosenberg and the Spy Network

Ethel Rosenberg was fully aware of her husband's activities. Feklissov recorded details of a meeting he had with the group: "Julius inquired of Ruth how she felt about the Soviet Union and how deep in general her Communist convictions went, whereupon she replied without hesitation that, to her, socialism was the sole hope of the world and the Soviet Union commanded her deepest admiration... Julius then explained his connections with certain people interested in supplying the Soviet Union with urgently needed technical information it could not obtain through the regular channels and impressed upon her the tremendous importance of the project in which David is now at work.... Ethel here interposed to stress the need for the utmost care and caution in informing David of the work in which Julius was engaged and that, for his own safety, all other political discussion and activity on his part should be subdued." (6)

However, as Alexander Feklissov, explained in his book, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs (1999): "Ethel Rosenberg... obviously shared Julius's ideals and was certainly aware of the fact that he worked for Soviet intelligence. However, she had never participated in his covert activities. The best proof is that she was never given a code name in secret cables with the Cener (even Ruth Greenglass, despite her rather small contribution, had a code name: Ossa). The Venona files confirm this." (7)

According to a NKVD message dated 27th November 1944 from Leonid Kvasnikov: "Information on Liberal's (Julius Rosenberg's wife). Surname that of her husband, first name Ethel, 29 years old. Married five years. Finished secondary school. A (Communist Party member) since 1938. Sufficiently well developed politically. Knows about her husband's work and the role of Meter (Joel Barr) and Nil (unidentified Soviet spy). In view of delicate health does not work. It characterized positively and as a devoted person." (8)

The Manhattan Project

Alexander Feklissov reported that in January 1945, Julius Rosenberg and David Greenglass met to discuss their attempts to obtain information on the Manhattan Project. "(Julius Rosenberg) and (David Greenglass) met at the flat of (Greenglass's) mother... (Rosenberg's) wife and (Greenglass) are brother and sister. After a conversation in which (Greenglass) confirmed his consent to pass us data about work in Camp 2... (Rosenberg) discussed with him a list of questions to which it would be helpful to have answers... (Greenglass) has the rank of sergeant. He works in the camp as a mechanic, carrying out various instructions from his superiors. The place where (Greenglass) works is a plant where various devices for measuring and studying the explosive power of various explosives in different forms (lenses) are being produced." (9)

Greenglass later claimed that as a result of this meeting he verbally described the "atom bomb" to Rosenberg. He also prepared some sketches and provided a written description of the lens mold experiments and a list of scientists working on the project. He was also asked the names of "some possible recruits... people who seemed sympathetic with Communism." Julius Rosenberg complained about his handwriting and arranged for Ethel Rosenberg to "type it up". According to Kathryn S. Olmsted: "Greenglass's knowledge was crude compared to the disquisitions on nuclear physics that the Russians received from Fuchs." (10)

The Soviet spy network suffered a set-back when Julius Rosenberg, was sacked from the Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, when they discovered that he had been a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). (11) NKVD headquarters in Moscow sent Leonid Kvasnikov a message on 23rd February, 1945: "The latest events with (Julius Rosenberg), his having been fired, are highly serious and demand on our part, first, a correct assessment of what happened, and second, a decision about (Rosenberg's) role in future. Deciding the latter, we should proceed from the fact that, in him, we have a man devoted to us, whom we can trust completely, a man who by his practical activities for several years has shown how strong is his desire to help our country. Besides, in (Rosenberg) we have a capable agent who knows how to work with people and has solid experience in recruiting new agents." (12)

Kvasnikov's main concern was that the FBI had discovered that Rosenberg was a spy. To protect the rest of the network, Feklissov was told not to have any contact with Rosenberg. However, the NKVD continued to pay Rosenberg "maintenance" and was warned not to take any important decisions about his future work without their consent. Eventually they gave him permission to take "a job as a radar specialist with Western Electric, designing systems for the B-29 bomber." (13)

After the war Rosenberg briefly worked at Emerson Radio, making $100 weekly with overtime but was laid off at the end of 1945. A few months later he established a small surplus products business and a machine shop, in which his brother-in-law, David Greenglass, invested. (14) He lived with his wife and two children in Knickerbocker Village. He continued working as a Soviet spy. According to one decoded message he "continued fulfilling the duties of a group handler, maintaining contact with comrades, rendering them moral and material contact with comrades, rendering them moral and material help while gathering valuable scientific and technical information." (15)

Arrest of David Greenglass

On 16th June, 1950, David Greenglass was arrested. The New York Tribune quoted him as saying: "I felt it was gross negligence on the part of the United States not to give Russia the information about the atom bomb because he was an ally." (16) According to the New York Times, while waiting to be arraigned, "Greenglass appeared unconcerned, laughing and joking with an FBI agent. When he appeared before Commissioner McDonald... he paid more attention to reporters' notes than to the proceedings." (17) Greenglass's attorney said that he had considered suicide after hearing of Gold's arrest. He was also held on $1000,000 bail.

On 6th July, 1950, the New Mexico federal grand jury indicted David Greenglass on a charge of conspiring to commit espionage in wartime on behalf of the Soviet Union. Specifically, he was accused of meeting with Harry Gold in Albuquerque on 3rd June, 1945, and producing "a sketch of a high explosive lens mold" and receiving $500 from Gold. It was clear that Gold had provided the evidence to convict Greenglass.

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

The New York Daily Mirror reported on 13th July that Greenglass had decided to join Harry Gold and testify against other Soviet spies. "The possibility that alleged atomic spy David Greenglass has decided to tell what he knows about the relay of secret information to Russia was evidenced yesterday when U. S. Commissioner McDonald granted the ex-Army sergeant an adjournment of proceedings to move him to New Mexico for trial." (18) Four days later the FBI announced the arrest of Julius Rosenberg. The New York Times reported that Rosenberg was the "fourth American held as a atom spy".(19)

The New York Daily News sent a journalist to Rosenberg's machinist shop. He claimed that the three employees were all non-union workers who had been warned by Rosenberg that there could be no vacations because the firm had made no money in the past year and a half. The employees also disclosed that at one time David Greenglass had worked at the shop as a business partner of Rosenberg. (20) Time Magazine noted that "alone of the four arrested so far, Rosenberg stoutly insisted on his innocence." (21)

Arrest of Julius Rosenberg

The Department of Justice issued a press release quoting J. Edgar Hoover as saying "that Rosenberg is another important link in the Soviet espionage apparatus which includes Dr. Klaus Fuchs, Harry Gold, David Greenglass and Alfred Dean Slack. Mr. Hoover revealed that Rosenberg recruited Greenglass... Rosenberg, in early 1945, made available to Greenglass while on furlough in New York City one half of an irregularly cut jello box top, the other half of which was given to Greenglass by Harry Gold in Albuquerque, New Mexico as a means of identifying Gold to Greenglass." The statement went onto say that Anatoli Yatskov, Vice Consul of the Soviet Consulate in New York City, paid money to the men. Hoover referred to "the gravity of Rosenberg's offense" and stated that Rosenberg had "aggressively sought ways and means to secretly conspire with the Soviet Government to the detriment of his own country." (22)

Julius Rosenberg refused to implicate anybody else in spying for the Soviet Union. Joseph McCarthy had just launched his attack on a so-called group of communists based in Washington. Hoover saw the arrest of Rosenberg as a means of getting good publicity for the FBI. However, he was desperate to get Rosenberg to confess. Alan H. Belmont reported to Hoover: "Inasmuch as it appears that Rosenberg will not be cooperative and the indications are definite that he possesses the identity of a number of other individuals who have been engaged in Soviet espionage... New York should consider every possible means to bring pressure on Rosenberg to make him talk, including... a careful study of the involvement of Ethel Rosenberg in order that charges can be placed against her, if possible." (23) Hoover sent a memorandum to the US attorney general Howard McGrath saying: "There is no question that if Julius Rosenberg would furnish details of his extensive espionage activities it would be possible to proceed against other individuals. Proceeding against his wife might serve as a lever in these matters." (24)

On 11th August, 1950, Ethel Rosenberg testified before a grand jury. She refused to answer all the questions and as she left the courthouse she was taken into custody by FBI agents. Her attorney asked the U.S. Commissioner to parole her in his custody over the weekend, so that she could make arrangements for her two young children. The request was denied. One of the prosecuting team commented that there "is ample evidence that Mrs. Rosenberg and her husband have been affiliated with Communist activities for a long period of time." (25) Rosenberg's two children, Michael Rosenberg and Robert Rosenberg, were looked after by her mother, Tessie Greenglass. Julius and Ethel were put under pressure to incriminate others involved in the spy ring. Neither offered any further information.

Curt Gentry, the author of J. Edgar Hoover, The Man and the Secrets (1991) has pointed out: "The FBI arrested Ethel Rosenberg. Despite the lack of evidence, her incarceration was an essential part of the Hoover's plan. With both Rosenbergs jailed - bail for each was set at $100,000, an unmeetable amount - the couple's two young sons were passed from relative to relative, none of whom wanted them, until they were placed in the Jewish Children's Home in the Bronx. According to matrons at the Women's House of Detention, Ethel missed the children terribly, suffered severe migraines, and cried herself to sleep at night. But Julius didn't break." (26)

Morton Sobell was the next person to be arrested. He had been the classmate of Julius Rosenberg. Sobell was an electrical engineer who had been employed on military work at Reeves Instrument Company in Manhattan. He had also worked with the General Electric Company in Schenectady and the Navy Bureau of Ordance in Washington. The New York Times reported that he was "the eighth U.S. citizen arrested on spy charges since British Physicist Klaus Fuchs began spilling what he knew of the busy Soviet espionage ring in the U.S." (27)

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg appeared in court and pleaded not guilty. One newspaper reported: "As they met inside the courtroom Rosenberg slipped his arm around the waist of his wife and the two walked before the bar. Throughout the proceeding the Rosenbergs whispered to one another, held hands and seemed oblivious to arguments concerning the charge. If convicted they could receive the death penalty." (28) At the same time it was reported that Senator Harley Kilgore was drafting a bill to "grant the FBI properly safeguarded war emergency powers to throw all Communists into concentration camps." (29) On 10th October, 1950, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, David Greenglass, Morton Sobell and Anatoli Yatskov were charged with espionage. (30)

On 7th February, 1950, Gordon Dean, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, contacted James McInerney, chief of the Justice Department's Criminal Division and asked him if Julius Rosenberg had made a confession? Dean recorded in his diary, McInerney said there is no indication of a confession at this point and he doesn't think there will be unless we get a death sentence. He talked to the judge and he is prepared to impose one if the evidence warrants." (31)

At a secret meeting the following day, twenty top government officials, including Dean met to discuss the Rosenberg case. Myles Lane told the meeting that Julius Rosenberg was the "keystone to a lot of other potential espionage agents" and that the Justice Department believed that the only thing that would break Rosenberg was "the prospect of a death penalty or getting the chair." Lane admitted that the case against Ethel Rosenberg was "not too strong" against her, it was "very important that she be convicted too, and given a stiff sentence." Dean stated: "It looks as though Rosenberg is the king pin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it." (32)

The problem of a weak case against Ethel Rosenberg was solved just ten days before the start of the trial when David and Ruth Greenglass were "reinterviewed". They were persuaded to change their original stories. David had said that he'd passed the atomic data he'd collected to Julius on a New York street corner. Now he stated that he'd given this information to Julius in the living room of the Rosenberg's New York apartment and that Ethel, at Julius's request, had taken his notes and "typed them up". In her reinterview Ruth expanded on her husband's version: "Julius then took the info into the bathroom and read it and when he came out he called Ethel and told her she had to type this info immediately... Ethel then sat down at the typewriter which she placed on a bridge table in the living room and proceeded to type the info which David had given to Julius." As a result of this new testimony, all charges against Ruth were dropped.

Trial of the Rosenbergs

The trial of Julius Rosenberg, Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell began on 6th March 1951. Irving Saypol opened the case: "The evidence will show that the loyalty and alliance of the Rosenbergs and Sobell were not to our country, but that it was to Communism, Communism in this country and Communism throughout the world... Sobell and Julius Rosenberg, classmates together in college, dedicated themselves to the cause of Communism... this love of Communism and the Soviet Union soon led them into a Soviet espionage ring... You will hear our Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Sobell reached into wartime projects and installations of the United States Government... to obtain... secret information... and speed it on its way to Russia.... We will prove that the Rosenbergs devised and put into operation, with the aid of Soviet... agents in the country, an elaborate scheme which enabled them to steal through David Greenglass this one weapon, that might well hold the key to the survival of this nation and means the peace of the world, the atomic bomb." (33)

The first witness of the prosecution was Max Elitcher. He had met Morton Sobell at Stuyvesant High School in New York City. Later they both studied electrical engineering at the College of the City of New York (CCNY). A fellow student at the CCNY was Julius Rosenberg. After graduation Elitcher and Sobell both found jobs at the Navy Bureau of Ordnance in Washington, where they shared an apartment and joined the Communist Party of the United States.

Elitcher claimed that in June 1944, he was phoned by Rosenberg: "I remembered the name, I recalled who it was, and he said he would like to see me. He came over after supper, and my wife was there and we had a casual conversation. After that he asked if my wife would leave the room, that he wanted to speak to me in private." Rosenberg then allegedly said that many people, including Sobell, were aiding Russia "by providing classified information about military equipments".

At the beginning of September 1944, Elitcher and his wife went on holiday with Sobell and his fiancee. Elitcher told his friend of Rosenberg's visit and his disclosure that "you, Sobell, were also helping in this." According to Elitcher, Sobell "became very angry and said "he should not have mentioned my name. He should not have told you that." Elitcher claimed that Rosenberg tried to recruit him again in September 1945. Rosenberg told Elitcher "that even though the war was over there was a continuing need for new military information for Russia."

Elitcher was approached by Sobell in 1947 who asked him if he "knew of any engineering students or engineering graduates who were progressive, who would be safe to approach on this question of espionage. When he decided to quit his Navy job in Washington in June 1948, Rosenberg tried to dissuade him as "he needed somebody to work at the Navy Department for this espionage purpose." When Elitcher refused to stay on, Rosenberg suggested that he get a job where military work was being done.

David Greenglass was questioned by the chief prosecutor assistant, Roy Cohn. Greenglass claimed that his sister, Ethel, influenced him to become a Communist. He remembered having conversations with Ethel at their home in 1935 when he was thirteen or fourteen. She told him that she preferred Russian socialism to capitalism. Two years later, her boyfriend, Julius, also persuasively talked about the merits of Communism. As a result of these conversations he joined the Young Communist League (YCL). (34)

Greenglass pointed out that Julius Rosenberg recruited him as a Soviet spy in September 1944. Over the next few months he provided some sketches and provided a written description of the lens mold experiments and a list of scientists working on the project. He was gave Rosenberg the names of "some possible recruits... people who seemed sympathetic with Communism." Greenglass also claimed that because of his poor handwriting his sister typed up some of the material. (35)

In June 1945 Greenglass claimed that Harry Gold visited him. "There was a man standing in the hallway who asked if I were Mr. Greenglass, and I said yes. He steeped through the door and he said, Julius sent me... and I walked to my wife's purse, took out the wallet and took out the matched part of the Jello box." Gold then produced the other part and he and David checked the pieces and saw they fitted. Greenglass did not have the information ready and asked Gold to return in the afternoon. He then prepared sketches of lens mold experiments with written descriptive material. When he returned Greenglass gave him the material in an envelope. Gold also gave Greenglass an envelope containing $500. (36)

Greenglass told the court that in February 1950, Julius Rosenberg came to see him. He gave him the news that Klaus Fuchs had been arrested and that he had made a full confession. This would mean that members of his Soviet spy network would also be arrested. According to Greenglass, Rosenberg suggested that he should leave the country. Greenglass replied: "Well, I told him that I would need money to pay my debts back... to leave with a clear head... I insisted on it, so he said he would get the money for me from the Russians." In May he gave him $1,000 and promised him $6,000 more. (He later gave him another $4,000.) Rosenberg also warned him that Harry Gold had been arrested and was also providing information about the spy ring. Rosenberg also said he had to flee as the FBI had identified Jacob Golos as a spy and he had been his main contact until his death in 1943.

Greenglass was cross-examined by Emanuel Bloch and suggested that his hostility towards Rosenberg had been caused by their failed business venture: "Now, weren't there repeated quarrels between you and Julius when Julius accused you of trying to be a boss and not working on machines?" Greenglass replied: "There were quarrels of every type and every kind... arguments over personality... arguments over money... arguments over the way the shop was run... We remained as good friends in spite of the quarrels." Bloch asked him why he had punched Rosenberg while in a "candy shop." Greenglass admitted that "it was some violent quarrel over something in the business." Greenglass complained that he had lost all of his money in investing in Rosenberg's business.

Testimony: Ruth Greenglass

The New York Times reported that Ruth Greenglass, the mother of a boy, four, and a girl, ten months, was a "buxom and self-possessed brunette" but looked older and her twenty-six years. It added that she testified "in seemingly eager, rapid fashion." (37) Ruth Greenglass recalled a conversation she had with Julius Rosenberg in November 1944: "Julius said that I might have noticed that for some time he and Ethel had not been actively pursuing any Communist Party activities, that they didn't buy the Daily Worker at the usual newsstand; that for two years he had been trying to get in touch with people who would assist him to be able to help the Russian people more directly other than just his membership in the Communist Party... He said that his friends had told him that David was working on the atomic bomb, and he went on to tell me that the atomic bomb was the most destructive weapon used so far, that it had dangerous radiation effects that the United States and Britain were working on this project jointly and that he felt that the information should be shared with Russia, who was our ally at the time, because if all nations had the information then one nation couldn't use the bomb as a threat against another. He said that he wanted me to tell my husband, David, that he should give information to Julius to be passed on to the Russians."

Ruth Greenglass admitted that in February 1945, Rosenberg paid her to go and live in Albuquerque so she was close to David Greenglass who was working in Los Alamos: "Julius said he would take care of my expenses; the money was no object; the important thing was for me to go to Albuquerque to live." Harry Gold would visit and exchange information for money. One payment in June was $500. She "deposited $400 in an Albuquerque bank, purchased a $50 defense bond (for $37.50)" and used the rest for "household expenses." (38)

Ruth Greenglass testified that she saw a "mahogany console table" in the Rosenberg's apartment in 1946. "Julius said it was from his friend and it was a special kind of table, and he turned the table on its side." A portion of the table was hollow "for a lamp to fit underneath it so that the table could be used for photograph purposes." Greenglass claimed that Rosenberg said he used the table to take "pictures on microfilm of the typewritten notes."

Testimony: Harry Gold

At the trial Harry Gold admitted that he became a Soviet spy in 1935. Time Magazine reported that "as precisely and matter-of-factly as a high-school teacher explaining a problem in geometry". (39) During the Second World War his main contact was Anatoli Yatskov. In January 1945 he met Klaus Fuchs at his sister's house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. "Fuchs was now stationed at a place called Los Alamos, New Mexico; that this was a large experimental station.... Fuchs told me that a tremendous amount of progress had been made. In addition, he had made mention of a lens, which was being worked on as a part of the atom bomb.... Yatskov told me to try to remember anything else that Fuchs had mentioned during our Cambridge meeting, about the lens." (40)

Yatskov told Gold to arrange a meeting with David Greenglass in Albuquerque. Yatskov then handed Gold a sheet of onionskin paper "and on it was typed... the name Greenglass." According to Gold the last thing on the paper was "Recognition signal. I come from Julius." Yatskov also gave Gold an odd-shaped "piece of cardboard, which appeared to have been cut from a packaged food of some sort" and said that Greenglass would have the matching piece. An envelope, which Yatskov said contained $500, was to be given to Greenglass or his wife.

Gold met Greenglass on 3rd June, 1945. "I saw a man of about 23... I said I came from Julius... I showed him the piece of cardboard... that had been given me by Yatskov... He asked me to enter. I did. Greenglass went to a women's handbag and brought out from it a piece of cardboard. We matched the two of them." The New York Times reported: "By an ironic quick of Gold's testimony, the cut-out portion of a Jello box became the first tangible bit of evidence to connect the Rosenbergs, the Greenglasses, Gold and Yatskov." (41)

On 26th December 1946, Harry Gold met Anatoli Yatskov in New York City. Gold told him he was now working for Abraham Brothman, a Soviet spy who had been named by Elizabeth Bentley as a spy. Yatskov was furious and he said: "You fool... You spoiled eleven years of work." Gold claimed in court that Yatskov "kept mumbling that I had created terrible damage and... then told me that he would not see me in the United States again." Records show that Yatskov and his family left the United States by ship on 27th December. (42)

Testimony: Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Bentley worked closely with Jacob Golos, Julius Rosenberg's main Soviet contact. She recalled that in the autumn of 1942 she accompanied Golos when he drove to Knickerbocker Village and told her "he had to stop by to pick up some material from a contact, an engineer." While she waited, Golos had met the contact and "returned to the car with an envelope of material."

Irving Saypol asked Bentley: "Subsequent to this occasion when you went to the vicinity of Knickerbocker Village with Golos.... did you have a telephone call from somebody who described himself as Julius?" She replied that on five of six occasions in 1942 and 1943 she received phone calls from a man called Julius. These messages were passed on to Golos. Judge Irving Kaufman commented that it would "be for the jury to infer... whether or not the Julius she spoke to... is the defendant Julius Rosenberg."

Testimony: Julius Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg was asked if he had ever been a member of the Communist Party on the United States. Rosenberg replied by invoking the Fifth Amendment. After further questioning he agreed that he sometimes read the party newspaper, the Daily Worker. He was also asked about his wartime views regarding the Soviet Union. He replied that he "felt that the Russians contributed the major share in destroying the Nazi army" and "should get as much help as possible." His opinion was "that if we had a common enemy we should get together commonly." He also admitted that he had been a member of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee.

Rosenberg was asked about the "mahogany console table" claimed by Ruth Greenglass to be in the Rosenberg's apartment in 1946. Rosenberg claimed he had purchased it from Macy's for $21. Irving Saypol replied: "Don't you know, Mr. Rosenberg, that you couldn't buy a console table in Macy's... in 1944 and 1945, for less than $85?" This was later found to be incorrect but at the time the impression was given that Rosenberg was lying.

The "mahogany console table" was not presented in the courtroom as evidence. It was claimed that it had been lost. Therefore it was not possible to examine it to see if Greenglass was right when she said that a portion of the table was hollow "for a lamp to fit underneath it so that the table could be used for photograph purposes." After the case had finished it the table was found and it did not have the section claimed by Greenglass. A brochure was also produced to suggest that Rosenberg might have purchased it for $21 at Macy's. (43)

Testimony: Ethel Rosenberg

Ethel Rosenberg was the final defence witness. The New York Times described her in court as a "little woman with soft and pleasant features". (44) During cross-examination she denied all allegations regarding espionage activity. She admitted that she owned a typewriter - she had purchased it when she was eighteen - and during her courtship had typed Julius's college engineering reports and prior to the birth of her first child, she did "a lot of typing" as secretary for the East Side Defense Council and the neighborhood branch of the Civil Defense Volunteer Organization. However, she insisted that she never had typed anything relating to government secrets. (45)

Irving Saypol pointed out that she had testified twice before the grand jury and both times she had invoked her constitutional privilege against self-incrimination. Much of her grand jury testimony was read in court, disclosing that many of the same questions she had refused to answer before the grand jury she later answered at her trial. The New York Times reported that she "had claimed constitutional privilege... even on questions that seemed harmless." (46) Ethel gave no specific explanation for her extensive use of the Fifth Amendment before the grand jury, but noted that both her husband and brother were under arrest at the time.

Several journalists covering the trial noticed that no FBI agents were called to testify. The reason for this was that if they appeared the lawyers could have asked questions and the answers would have been very unfavourable to the prosecution. "For instance, what was the evidence of espionage activity against Ethel Rosenberg? Just one question of this kind could make the entire structure disintegrate." (47)

Summations & Verdict

Emanuel Bloch argued: "Is there anything here which in any way connects Rosenberg with this conspiracy? The FBI "stopped at nothing in their investigation... to try to find some piece of evidence that you could feel, that you could see, that would tie the Rosenbergs up with this case... and yet this is the... complete documentary evidence adduced by the Government... this case, therefore, against the Rosenbergs depends upon oral testimony."

Bloch attacked David Greenglass, the main witness against the Rosenbergs. Greenglass was "a self-confessed espionage agent," was "repulsive... he smirked and he smiled... I wonder whether... you have ever come across a man, who comes around to bury his own sister and smiles." Bloch argued that Greenglass's "grudge against Rosenberg" over money was not enough to explain his testimony. The explanation was that Greenglass "loved his wife" and was "willing to bury his sister and his brother-in-law" to save her. The "Greenglass Plot" was to lessen his punishment by pointing his finger at someone else. Julius Rosenberg was a "clay pigeon" because he had been fired from his government job for being a member of the Communist Party of the United States in 1945. (48)

In his reply, Irving Saypol, pointed out that "Mr Bloch had a lot of things to say about Greenglass... but the story of the Albuquerque meeting... does not come to you from Greenglass alone. Every word that David and Ruth Greenglass spoke on this stand about that incident was corroborated by Harry Gold... a man concerning whom there cannot even be a suggestion of motive... He had been sentenced to thirty years... He can gain nothing from testifying as he did in this courtroom and tried to make amends. Harry Gold, who furnished the absolute corroboration of the testimony of the Greenglasses, forged the necessary link in the chain that points indisputably to the guilt of the Rosenbergs."

In his summing up Judge Irving Kaufman was considered by many to have been highly subjective: "Judge Kaufman tied the crimes the Rosenbergs were being accused of to their ideas and the fact that they were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. He stated that they had given the atomic bomb to the Russians, which had triggered Communist aggression in Korea resulting in over 50,000 American casualties. He added that, because of their treason, the Soviet Union was threatening America with an atomic attack and this made it necessary for the United States to spend enormous amounts of money to build underground bomb shelters." (49)

The jury found all three defendants guilty. Thanking the jurors, Judge Kaufman, told them: "My own opinion is that your verdict is a correct verdict... The thought that citizens of our country would lend themselves to the destruction of their own country by the most destructive weapons known to man is so shocking that I can't find words to describe this loathsome offense." (50) Judge Kaufman sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the death penalty and Morton Sobell to thirty years in prison.

A large number of people were shocked by the severity of the sentence as they had not been found guilty of treason. In fact, they had been tried under the terms of the Espionage Act that had been passed in 1917 to deal with the American anti-war movement. Under the terms of this act, it was a crime to pass secrets to the enemy whereas these secrets had gone to an ally, the Soviet Union. During the Second World War several American citizens were convicted of passing information to Nazi Germany. Yet none of these people were executed.

Response to the Conviction

It soon became clear that the main objective of imposing the death penalty was to persuade Julius Rosenberg and others to confess. Howard Rushmore, writing in the New York Journal-American, he argued: "A few months in the death house might loosen the tongues of one or more of the three traitors and lead to the arrest of... other Americans who were part of the espionage apparatus." (51) Eugene Lyons commented in the New York Post: "The Rosenbergs still have a chance to save their necks by making full disclosure about their spy ring - for Judge Kaufman, who conducted the trial so ably, has the right to alter his death sentence." (52)

J. Edgar Hoover was one of those who opposed the sentence. As Curt Gentry, the author of J. Edgar Hoover, The Man and the Secrets (1991) has pointed out: "While he thought the arguments against executing a woman were nothing more than sentimentalism, it was the 'psychological reaction' of the public to executing a wife and mother and leaving two small children orphaned that he most feared. The backlash, he predicted, would be an avalanche of adverse criticism, reflecting badly on the FBI, the Justice Department, and the entire government." (53)

However, the vast majority of newspapers in the United States supported the death-sentence of the Rosenbergs. Only the Daily Worker, the journal of the Communist Party of the United States, and the Jewish Daily Forward took a strong stance against the decision. (54) Julius Rosenberg wrote to Ethel that he was "amazed" by the "newspaper campaign organized against us". However, he insisted that "we will never lend ourselves to the tools to implicate innocent people, to confess crimes we never did and to help fan the flames of hysteria and help the growing witch hunt." (55) In another letter five days later he pointed out that it was "indeed a tragedy how the lords of the press can mold public opinion by printing... blatant falsehoods." (56)

Dorothy Thompson was one of the only columnists who complained that the sentence was too harsh. Writing in The Washington Star she argued: "The death sentence... depresses me... in 1944, we were not at war with the Soviet Union... Indeed, it is unlikely that had they been tried in 1944 they would have received any such sentence." (57) Thompson's views were unpopular in the United States, it did reflect the views being expressed in other countries. The case created a great deal of controversy in Europe where it was argued that the Rosenbergs were victims of anti-semitism and McCarthyism.

Judge Irving Kaufman suggested that the campaign against the death sentences was part of a communist conspiracy. "I have been frankly hounded, pounded by vilification and by pressurists... I think that it is not a mere accident that some people have been aroused in these countries. I think it has been by design." (58) Time Magazine took a similar view and argued "Communists the world over... had an issue they rode hard... the American couple who sit in the death house at Sing Sing, scheduled to be electrocuted." (59) However, the The New York Tribune pointed out that it was not only communists who were complaining about the death sentences: "The vast majority of non-Communist newspapers in France continued to urge today that the death sentences of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg... be commuted to life imprisonment." (60)

Imprisonment

Miriam Moskowitz got to know Ethel Rosenberg while she was in prison: "The day the jury brought in a guilty verdict, Ethel was moved to my floor and assigned a cell at the end of the corridor nearest the guards, which permitted them to keep her within sight at all times. Presumably someone in the Department of Justice wanted to be sure Ethel Rosenberg would not do away with herself. (She commented to me later that it was ironic that they could never understand that this would be the least likely thing she could ever do.) Her corridor was now diagonally opposite mine. I watched her settling in from behind the bars of my corridor and when the gates were opened at recreation time I walked over to say hello. She greeted me warmly and she, who faced such a monumentally more severe punishment than I did, she was concerned for me. Was I bearing up well?"

Moskowitz claims in her book, Phantom Spies, Phantom Justice (2010) that Ethel was popular with the other prisoners: "She was never judgmental about whatever brought them to this hellhole; she would share anecdotes with them about her children and listen sympathetically to their sorry stories. Hers was a gentle presence - there was a dignity about her and as she became known to those women, their routine cursing and descriptively angry language became muted when she was near. Many of the women were young and barely out of their teens. When melancholy seized them she became a surrogate big sister and comforted them. The outside world usually thinks of a jail population as the most outcast, most immoral and most destructive part of society; nevertheless, the women saw themselves as loyal and patriotic Americans, and they separated their legal misdeeds from their love of country. One accused of treason or espionage, as Ethel was, would have been regarded with contempt and overt hostility by those women, yet they did not believe the government's accusations about her. They liked her, they accepted her, and they gave her their endorsement."

The two women became close friends. "We had, tacitly, set limits on our conversation so we never discussed our legal cases; but sometimes Ethel would remark bitterly about her brother's scabby behavior towards her. She remembered David as a child, cute and cuddly and as the one who was their mother's special joy, who much indulged him. Trying to comprehend the freakish turn of his behavior, Ethel recalled that he was always overconfident and reckless, and life had tripped him up many times. Now, she reasoned, he had walked into the FBI's arena underestimating how they could forge steel traps out of airy spiderwebs; at the same time he was sublimely, foolishly cocksure about his ability to combat their efforts. Ethel knew first-hand the awesome pressure they could exert and she visualized that when they threatened to arrest his wife and to anchor him to the death penalty, he quickly collapsed and followed where they led him. She was sure that ultimately he would be unable to live with what he had done to her." (61)

Pleas for Clemency

In December 1952 the Rosenbergs appealed their sentence. Myles Lane, for the prosecution argued: "In my opinion, your Honor, this and this alone accounts for the stand which the Russians took in Korea, which... caused death and injury to thousands of American boys and untold suffering to countless others, and I submit that these deaths and this suffering, and the rest of the state of the world must be attributed to the fact that the Soviets do have the atomic bomb, and because they do... the Rosenbergs made a tremendous contribution to this despicable cause. If they (the Rosenbergs) wanted to cooperate... it would lead to the detection of any number of people who, in my opinion, are today doing everything that they can to obtain additional information for the Soviet Union... this is no time for a court to be soft with hard-boiled spies.... They have showed no repentance; they have stood steadfast in their insistence on their innocence." (62)

Judge Irving Kaufman agreed and responded with the judgment: "I am again compelled to conclude that the defendants' guilt... was established beyond doubt... Their traitorous acts were of the highest degree... It is apparent that Russia was conscious of the fact that the United States had the one weapon which gave it military superiority and that, at any price, it had to wrest that superiority from the United States by stealing the secret information concerning that weapon... Neither defendant has seen fit to follow the course of David Greenglass and Harry Gold. Their lips have remained sealed and they prefer the glory which they believe will be theirs by the martyrdom which will be bestowed upon them by those who enlisted them in this diabolical conspiracy (and who, indeed, desire them to remain silent)... I still feel that their crime was worse than murder... The application is denied." (63)

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg now appealed their sentence to President Harry S. Truman. However, Truman vacated the Presidency on 20th January, 1953, without acting on the Rosenbergs's clemency appeals. He had passed the problem to his successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower. It was reported that he received nearly fifteen thousand clemency letters in the first week of his administration. He received a great deal of advice from columnists in the press. George E. Sokolsky, wrote in the New York Journal-American: "Everything has been tried by the Rosenbergs except the only step that can justify their existence as human beings: they have never confessed; they have shown no contrition; they have not been penitent. They have been arrogant and tight-lipped... It is impossible to forgive these spies; it would be possible to commute their sentences, if they told the story fully, more than we now know even after these trials... Klaus Fuchs confessed. David Greenglass confessed. Harry Cold confessed. The Rosenbergs remain adamant... let them go to the devil." (64)

President Eisenhower made his decision on 11th February, 1953: "I have given earnest consideration to the records in the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and to the appeals for clemency made on their behalf.... The nature of the crime for which they have been found guilty and sentenced far exceeds that of the taking of the life of another citizen: it involves the deliberate betrayal of the entire nation and could very well result in the death of many, many thousands of innocent citizens. By their act these two individuals have in fact betrayed the cause of freedom for which free men are fighting and dying at this very hour.... There has been neither new evidence nor have there been mitigating circumstances which would justify altering this decision, and I have determined that it is my duty, in the interest of the people of the United States, not to set aside the verdict of their representatives." (65)

In a letter to his son, Eisenhower went into more detail about his decision: "It goes against the grain to avoid interfering in the case where a woman is to receive capital punishment. Over against this, however, must be placed one or two facts that have greater significance. The first of these is that in this instance it is the woman who is the strong and recalcitrant character, the man is the weak one. She has obviously been the leader in everything they did in the spy ring. The second thing is that if there would be any commuting of the woman's sentence without the man's then from here on the Soviets would simply recruit their spies from among women." (66)

Execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg remained on death row for twenty-six months. Two weeks before the date scheduled for their deaths, the Rosenbergs were visited by James V. Bennett, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. After the meeting they issued a statement: "Yesterday, we were offered a deal by the Attorney General of the United States. We were told that if we cooperated with the Government, our lives would be spared. By asking us to repudiate the truth of our innocence, the Government admits its own doubts concerning our guilt. We will not help to purify the foul record of a fraudulent conviction and a barbaric sentence. We solemnly declare, now and forever more, that we will not be coerced, even under pain of death, to bear false witness and to yield up to tyranny our rights as free Americans. Our respect for truth, conscience and human dignity is not for sale. Justice is not some bauble to be sold to the highest bidder. If we are executed it will be the murder of innocent people and the shame will be upon the Government of the United States."(67)

The case went before the Supreme Court. Three of the Justices, William Douglas, Hugo Black and Felix Frankfurter, voted for a stay of execution because they agreed with legal representation that the Rosenbergs had been tried under the wrong law. It was claimed that the 1917 Espionage Act, under which the couple had been indicted and sentenced, had been superseded by the penalty provisions of the 1946 Atomic Energy Act. Under the latter act, the death sentence may be imposed only when a jury recommends it and the offense was committed with intent to injure the United States. However, the other six voted for the execution to take place.

The FBI agent, Robert J. Lamphere, who was an important figure in the investigation of the Rosenbergs, admitted in his autobiography, The FBI-KGB War (1986) that the main reason Ethel Rosenberg was arrested is that they thought it would make Julius confess: "Al Belmont had gone up to Sing Sing to be available if either or both of the Rosenbergs should decide to save themselves by confessing, and to be on hand as the expert if the question should arise whether or not a last-minute confession was actually furnishing substantial information on espionage. I was sitting in Mickey Ladd's office, with several other people; we had an open telephone line to Belmont in Sing Sing, and as the final minutes came closer, the tension mounted. I wanted very much for the Rosenbergs to confess - we all did - but I was fairly well convinced by this time that they wished to become martyrs, and that the KGB knew damned well that the U.S.S.R. would be better off if their lips were sealed tight. Belmont telephoned us to say that the Rosenbergs had refused for the last time to save themselves by confession." (68)

The Rosenbergs were executed on 19th June, 1953. "Julius Rosenberg, thirty-five, wordlessly went to his death at 8:06 P.M. Ethel Rosenberg, thirty-seven, entered the execution chamber a few minutes after her husband's body had been removed. Just before being seated in the chair, she held out her hand to a matron accompanying her, drew the other woman close, and kissed her lightly on the cheek. She was pronounced dead at 8:16 P.M." According to the New York Times the Rosenbergs went to their deaths "with a composure that astonished the witnesses." (69)

The execution resulted in large protests all over Europe. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in Libération: "Now that we have been made your allies, the fate of the Rosenbergs could be a preview of our own future. You, who claim to be masters of the world, had the opportunity to prove that you were first of all masters of yourselves. But if you gave in to your criminal folly, this very folly might tomorrow throw us headlong into a war of extermination... By killing the Rosenbergs you have quite simply tried to halt the progress of science by human sacrifice. Magic, witch hunts, auto-da-fe's, sacrifices - we are here getting to the point: your country is sick with fear... you are afraid of the shadow of your own bomb." (70)

This was in direct contrast to the way the American media dealt with the issue. The New York Times reported the day after the execution: "In the record of espionage against the United States there had been no case of its magnitude and its stern drama. The Rosenbergs were engaged in funneling the secrets of the most destructive weapon of all time to the most dangerous antagonist the United States ever confronted - at a time when a deadly atomic arms race was on. Their crime was staggering in its potential for destruction. It stirred the fears and the emotions of the American people... The prevailing opinion in the United States... is that the Rosenbergs for two years had access to every court in the land and every organ of public opinion, that no court found grounds for doubting their guilt, that they were the only atom spies who refused to confess and that they got what they deserved." (71)

The execution of Ethel Rosenberg caused particular concern. Jacques Monod argued in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: "We could not understand that Ethel Rosenberg should have been sentenced to death when the specific acts of which she was accused were only two conversations; and we were unable to accept the death sentence as being justified by the 'moral support' she was supposed to have given her husband. In fact the severity of the sentence, even if one provisionally accepted the validity of the Greenglass testimony, appeared out of all measure and reason to such an extent as to cast doubt on the whole affair, and to suggest that nationalistic passions and pressure from an inflamed public opinion, had been strong enough to distort the proper administration of justice." (72)

The Struggle for Justice

Joanna Moorhead later reported: "From the time of their parents' arrests, and even after the execution, they (Rosenberg's two sons) were passed from one home to another - first one grandmother looked after them, then another, then friends. For a brief spell, they were even sent to a shelter. It seems hard for us to understand, but the paranoia of the McCarthy era was such that many people - even family members - were terrified of being connected with the Rosenberg children, and many people who might have cared for them were too afraid to do so." (73) Abe Meeropol and his wife eventually agreed to adopt Michael Rosenberg and Robert Rosenberg. According to Robert: "Abel didn't get any work as a writer throughout most of the 1950s... I can't say he was blacklisted, but it definitely looks as though he was at least greylisted."

In 1997, a senior Soviet agent, Alexander Feklissov, gave an interview to the The Washington Post where he claimed that Julius Rosenberg passed valuable secrets about U.S. military electronics but played only a peripheral role in Soviet atomic espionage. And he said Ethel Rosenberg did not actively spy but probably was aware that her husband was involved. Feklissov said neither he nor any other Soviet intelligence agent met Ethel Rosenberg. "She had nothing to do with this. She was completely innocent." (74)

Feklissov published The Man Behind the Rosenbergs in 1999. He admitted that both Rosenberg and Morton Sobell were spies. "This is the untold story that I have attempted to reconstruct as truthfully and in as much detail as I could... The pages that follow will distress those few persons still alive, the two Rosenberg sons and Morton Sobell, who have already been sufficiently traumatized by this event. However, I am convinced that to hear the truth is better than uncertainty and dark suspicion." (75)

In December 2001, Sam Roberts, a New York Times reporter, traced David Greenglass, who was living under an assumed name with Ruth Greenglass. Interviewed on television under a heavy disguise, he acknowledged that his and his wife's court statements had been untrue. "Julius asked me to write up some stuff, which I did, and then he had it typed. I don't know who typed it, frankly. And to this day I can't even remember that the typing took place. But somebody typed it. Now I'm not sure who it was and I don't even think it was done while we were there."

David Greenglass said he had no regrets about his testimony that resulted in the execution of Ethel Rosenberg. "As a spy who turned his family in, I don't care. I sleep very well. I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister... You know, I seldom use the word sister anymore; I've just wiped it out of my mind. My wife put her in it. So what am I going to do, call my wife a liar? My wife is my wife... My wife says, 'Look, we're still alive'." (76)

Jon Wiener has argued that both Klaus Fuchs and Theodore Hall were atomic spies: "Two scientists at Los Alamos, Klaus Fuchs and Theodore Hall, did convey valuable atomic information to the Soviets; but neither had any connection to the Communist Party... The decoded Soviet cables show that Ethel Rosenberg was not a Soviet spy and that, while Julius had passed non-atomic information to the Soviets, the trial case against them was largely fabricated... Why didn't the FBI go after Hall? Did the government execute the Rosenbergs and let Hall go because it didn't want to admit it had prosecuted the wrong people as atom spies?" (77)

In 2010 Walter Schneir, the author of Invitation to an Inquest (1983), published a new book on the case, Final Verdict. Schneir admitted that after reading the Venona transcripts, he now realised that Julius Rosenberg had been guilty of spying for the Soviet Union. "The charge in the Rosenberg trial was conspiracy to commit espionage; the defendants were all alleged to have been participants in a scheme aimed at obtaining national defence information for the benefit of the Soviet Union. That was certainly true of Julius." However, he remained convinced that Ethel was not guilty of the charges and that her arrest was an attempt "to convict both Rosenbergs, by any means necessary, and obtain severe sentences in the hope that the threat to Ethel would cause Julius to break." (78)

Primary Sources

(1) Judge Irving Kaufman, sentencing Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg to death (5th April, 1951)

The evidence indicated quite clearly that Julius Rosenberg was the prime mover in this conspiracy. However, let no mistake be made about the role which his wife, Ethel Rosenberg, played in this conspiracy. Instead of deterring him from pursuing his ignoble cause, she encouraged and assisted the cause. She was a mature woman - almost three years older than her husband and almost seven years older than her younger brother. She was a full-fledged partner in this crime.

Indeed the defendants Julius and Ethel Rosenberg placed their devotion to their cause above their own personal safety and were conscious that they were sacrificing their own children, should their misdeeds be detected - all of which did not deter them from pursuing their course. Love for their cause dominated their lives - it was even greater than their love for their children.

The sentence of the Court upon Julius and Ethel Rosenberg is, for the crime for which you have been convicted, you are hereby sentenced to the punishment to death, and it is ordered upon some day within the week beginning with Monday, May 21st, you shall be executed according to law.

(2) Ethel Rosenberg, letter to Julius Rosenberg, on hearing that their conviction had been upheld by the U.S. Circuit Court (26th February, 1952)

Last night at 10.00 o'clock, I heard the shocking news. At the present moment, with little or no detail to hand, it is difficult for me to make any comment, beyond the expression of horror at the shameless haste with which the government appears to be pressing for our liquidation.

(3) Julius Rosenberg, letter to Ethel Rosenberg (13th April, 1952)

Keep your chin up Ethel if we must suffer through this nightmare then in the manner we conduct ourselves we will contribute to the general welfare of the people by serving notice on the tyrants that they cannot get away with political frame-ups such as ours. It takes a lot of time and hard work to get them to overcome their inertia but now that grass root sentiments are aroused public opinion will have its effect. We've left a big chunk of suffering behind us these last two years and we are coming closer to our emancipation from all this torture.

(4) Julius Rosenberg, letter to Ethel Rosenberg (31st May, 1953)

What does one write to his beloved when faced with the very grim reality that in eighteen days, on their 14th wedding anniversary, it is ordered that they be put to death?

Over and over again, I have tried to analyze in the most objective manner possible the answers to the position of our government in our case. Everything indicates only one answer - that the wishes of certain madmen are being followed in order to use this case as a coercive bludgeon against all dissenters.

I know that our children and our family are suffering a great deal right now and it is natural that we be concerned for their welfare. However, I think we will have to concentrate our strength on ourselves. First, we want to make sure that we stand up under the terrific pressure, and then we ought to try to contribute some share to the fight.

(5) Ethel Rosenberg, clemency petition to President Harry S. Truman (9th January, 1953)

My husband and I testified in our own defense. We denied, generally, and in detail, every part of the evidence introduced by the Government to connect us with a conspiracy to commit espionage. We showed that, during the years in question, we lived a steady normal existence. Even as late as May 1950, during the period when the Government claimed we were preparing for flight, my husband depleted our meager cash reserves and obligated himself, on a long term basis, to buy out the holder of the preferred stock of the business in which he was engaged, to gain absolute ownership and control.

Upon the birth of our two sons, I ceased my outside employment, and discharged the responsibility of mother and housewife. My husband, a graduate engineer, held a regular succession of low-salaried positions until his entrance into the machine shop enterprise with David Greenglass. The modesty of our standard of living, bordering often on poverty, discredits David's depiction of my husband as the pivot and pay-off man of a widespread criminal combination, fed by a seemingly limitless supply of 'Moscow gold'...

Our knowledge of the existence of an atom-bomb came with its explosion at Hiroshima, and David's connection with it at Los Alamos, from his revelations to us on his discharge from the Army in 1946.

We knew neither Gold nor Yakovlev, our alleged co-conspirators, nor Bentley-facts which the Government did not controvert.

Our relations with Sobell, our co-defendant, were confined to sporadic social visits. Following a complete six-year break, after graduation from college, our ties with Elitcher assumed similar, but even more tenuous, character.

Our relationship with the Greenglasses, both during and after the war, was on a purely familial and social level, the cordiality becoming strained to the breaking, however, with the advent of bitter quarrels which arose in the course of our post-war business ties...

Petitioner respectfully prays that she be granted a pardon or commutation of sentence for the following reasons:

First: The primary reason I assert, and my husband with me, is that we are innocent.

We stand convicted of the conspiracy with which we were charged. We are conscious that were we to accept this verdict, express guilt, penitence and remorse, we might more readily obtain a mitigation of our sentences.

But this course is not open to us.

We are innocent, as we have proclaimed and maintained from the time of our arrest. This is the whole truth. To forsake this truth is to pay too high a price even for the priceless gift of life-for life thus purchased we could not live out in dignity and self-respect.

It should not be difficult for Americans to understand this simple concept to be the force that gives us strength-even in the face of imminent death, knowing well that the abandonment of principle might, alone, save our lives - to adhere to the continued assertion and profession of our innocence...

Yet we have been told again and again, until we have become sick at heart, that our proud defense of our innocence is arrogant, not proud, and motivated not by a desire to maintain our integrity, but to achieve the questionable "glory" of some undefined "martyrdom."

This is not so. We are not martyrs or heroes, nor do we wish to be. We do not want to die. We are young, too young, for death. We long to see our two young sons, Michael and Robert, grown to full manhood. We desire with every fibre to be restored sometime to our children and to resume the harmonious family life we enjoyed before the nightmare of our arrests and convictions....

Second: We understand, however, that the President, like the courts, considers himself bound by the verdict of guilt, although, on the evidence, a contrary conclusion may be admissible.

But many times before there has been too unhesitating reliance on the verdict of the moment and regret for the death that closed the door to remedy when the truth, as it will, has risen...

We say to you, Mr. President, that the character of evidence on which we were convicted, and the force of the impact of certain circumstances in our case upon the mind of the jury, cannot assure the reasonable mind that this verdict was not corrupt.

In the summer of 1950... the general public fear engendered by the announced mastery of the atom bomb by the Soviet Union, was aggravated by the increased international tensions occasioned by the Korean War...

When we were arrested as spies for the Soviet Union, labeled as "Communists," charged, in the main, with theft of atomic-bomb information from the Los Alamos Project, the mere accusation was enough to arouse deep passions, violent antipathies, and fears as profound as the instinct of self-preservation...

It was hammered home, and kept alive by a virtual avalanche of publicity which saturated the communal mind with a consciousness that our country was imminently in danger of atomic attack and devastation by the Soviet Union, which had acquired the bomb by reason of its having obtained the "secret," from an espionage apparatus, ideologically motivated, of which we were "aggressive" members....

From this community the jurors who tried us were chosen. Should this not temper reliance-to death-on this verdict of a jury, in which the unconscious influence of the enveloping atmosphere may have overridden the overt desire to be fair and seduced it into a more ready acceptance for the prosecution's evidence as against our defense?...

Third: The Government's case against us stands or falls on the testimony of David Greenglass and Ruth, his wife.... How firm is a verdict predicated upon the testimony of "accomplices"? Even the rigorous canons of the law recognize that the overriding motive for falsehood requires that the accusations of a trapped criminal, testifying to mitigate or avoid his own punishment, be taken with care and caution, and brand a prosecution founded on such evidence as "weak" and suspect.

We have never been able to comprehend that civilized and compassionate consciences could accept a smiling "Cain" like David Greenglass - or the "serpent," Ruth, his wife - who would slay not only his sister, but his sister's husband, and orphan two small children of his own blood.

We have always said that David, our brother, knowing well the consequences of his acts, bargained our lives away for his life and his wife's. Ruth goes free, as all the world now knows; David's freedom, too, is not so far off that he will not have many years to live a life-if we should die-that, perhaps, only a David Greenglass could suffer to live...

Fourth: Only one tribunal, the sentencing court, has asserted the correctness of our sentences to death, and only one court has affirmed it: the sentencing court. In other words, only one human being in a position of power has said we ought to die.

Although our case was appealed to the higher courts, the appellate tribunals, denying their power to review the discretion of the sentencing judge, have not, on the assumption of our guilt, ruled on the propriety of the magnitude of the sentences of death.

You, Mr. President, are the first one who is empowered to review these sentences-and the last one...

We are told that the "confessions" and "cooperation" of Greenglass and Gold and others earned them more lenient sentences. While this is recognized practice, the coercive power of sentence beyond that justified by the nature of the criminal act cannot legitimately be made to substitute for the proscribed "thumbscrew and rack" to secure confessions which cannot in truth and good conscience be forthcoming...

Scientific judgment undermines the validity of the trial judge's claim that our alleged conduct, did or could have, put "into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb."

The judge, obdurately holding to his irrational consideration... reaffirmed our death sentences... The facts of our case have touched the conscience of civilization. The compassion of men sees us as victims caught in the terrible interplay of clashing ideologies and feverish international enmities. Adjudged war criminals, guilty of mass murders and the most ghastly crimes, are daily being delivered to freedom, while we are being delivered to death...

We appeal to your mind and conscience, Mr. President, to take counsel with the reason of others and with the deepest human feelings that treasure life and shun its taking. To let us live will serve all and the common good. If we are innocent, as we proclaim, we shall have the opportunity to vindicate ourselves. If we have erred, as others say, then it is in the interest of the United States not to depart from its heritage of open-heartedness and its ideals of equality before the law by stooping to a vengeful and savage deed.

(6) George E. Sokolsky, New York Journal-American (9th January, 1953)

Everything has been tried by the Rosenbergs except the only step that can justify their existence as human beings: they have never confessed; they have shown no contrition; they have not been penitent. They have been arrogant and tight-lipped... It is impossible to forgive these spies; it would be possible to commute their sentences, if they told the story fully, more than we now know even after these trials... Klaus Fuchs confessed. David Greenglass confessed. Harry Cold confessed. The Rosenbergs remain adamant... let them go to the devil.

(7) Dwight D. Eisenhower, statement (11th February, 1953)

I have given earnest consideration to the records in the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and to the appeals for clemency made on their behalf....

The nature of the crime for which they have been found guilty and sentenced far exceeds that of the taking of the life of another citizen: it involves the deliberate betrayal of the entire nation and could very well result in the death of many, many thousands of innocent citizens. By their act these two individuals have in fact betrayed the cause of freedom for which free men are fighting and dying at this very hour.

We are a nation under law.... All rights of appeal were exercised and the conviction of the trial court was upheld after four judicial reviews, including that of the highest court in the land.

I have made a careful examination into this case and am satisfied that the two individuals have been accorded their full measure of justice.

There has been neither new evidence nor have there been mitigating circumstances which would justify altering this decision, and I have determined that it is my duty, in the interest of the people of the United States, not to set aside the verdict of their representatives.

(8) Time Magazine (23rd February, 1953)

Dwight Eisenhower's answer all but closed the door of doom on the Rosenbergs. There are still a few desperate delaying actions to be made - and Lawyer Emanuel Bloch might succeed in winning more borrowed time - but the only real opportunity of escape lay with the Rosenbergs themselves. If they broke their long silence - if they confessed the secrets of their spy ring-then the President might consider a new appeal for clemency. But up to now the Rosenbergs have clung to their dark secrets, have shown no flicker of regret.

(9) Statement issued by the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg after the visit of James V. Bennett, Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (May, 1953)

Yesterday, we were offered a deal by the Attorney General of the United States. We were told that if we cooperated with the Government, our lives would be spared.

By asking us to repudiate the truth of our innocence, the Government admits its own doubts concerning our guilt. We will not help to purify the foul record of a fraudulent conviction and a barbaric sentence.

We solemnly declare, now and forever more, that we will not be coerced, even under pain of death, to bear false witness and to yield up to tyranny our rights as free Americans.

Our respect for truth, conscience and human dignity is not for sale. Justice is not some bauble to be sold to the highest bidder.

If we are executed it will be the murder of innocent people and the shame will be upon the Government of the United States.

History will record, whether we live or not, that we were victims of the most monstrous frame-up in the history of our country.

(10) Jacques Monod, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (October, 1953)

As you may know, the execution of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg has aroused profound emotions in Europe, especially in France. It has also been the cause, or sometimes the occasion, of strong hostility and severe criticism being expressed in the press or by the public (I am referring here to the non-Communist press and public). In taking the liberty of writing to you on this subject I am urged, not by the desire to express criticism or reprobation but by my love and admiration for your country where I have many close friends.

As a scientist, I naturally address myself to scientists. Moreover, I know that American scientists respect their profession, and are aware that it involves a permanent pact with objectivity and truth - and that indeed wherever objectivity, truth, and justice are at stake, a scientist has the duty to form an opinion, and defend it. This, I hope, will be accepted as a valid explanation and excuse for my writing this letter. In any case, whether one agrees or not with what I think must be said, I beg that this letter be taken for what it is: a manifestation of deep sympathy and concern for America.

First of all, Americans should be fully aware of the extraordinary amplitude and unanimity of the movement which developed in France. Everybody here, in every walk of life, and independent of all political affiliations, followed the last stages of the Rosenberg case with anxiety, and the tragic outcome evoked anguish and consternation everywhere. Have Americans realized, were they informed, that pleas for mercy were sent to President Eisenhower not only by thousands of private individuals and groups, including many of the most respected writers and scientists, not only by all the highest religious leaders, not only by entire official bodies such as the (conservative) Municipal Council of Paris, but by the President of the Republic himself, who was thus obeying and expressing the unanimous wish of the French people. As your New York Times remarked with some irony and complete truth, France achieved a unanimity in the Rosenberg case that she could never hope to achieve on a domestic issue.

To a certain extent these widespread reactions were due to the simple human appeal of the case: this young couple, united in death by a frightful sentence which made orphans of their innocent children, the extraordinary courage shown by Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, their letters to each other, simple and moving. All this naturally evoked compassion, but it would be wrong to think that the French succumbed to a purely sentimental appeal to pity. Public opinion, and first of all the intellectual circles, were primarily sensitive to the legal and ethical aspects of the case, which were widely publicized, analyzed, and discussed.

If I may be allowed, I should like to review briefly the points which appeared most significant to us in forming an opinion on the whole affair.

The first was that the entire accusation, hence the whole case of the American government, rested upon the testimony of avowed spies, the Greenglass couple, of whom David received a light sentence after turning state's evidence (fifteen years reducible to five on good behavior), while his wife Ruth was not even indicted. The dubious value of testimony from such sources was apparent to everyone.

Moreover, leaving the ethical and legal doubts aside, is it probable or even possible that a simple mechanic such as David Greenglass, with no scientific training, could have chosen, assimilated, and memorized secrets of decisive atomic importance, under the directions of the similarly untrained Julius Rosenberg? Scientists here always found this difficult to believe, and their doubts were confirmed when Urey himself clearly stated in a letter to President Eisenhower that he considered it impossible...

Greenglass is supposed to have revealed to the Russians the secrets of the atomic bomb. Though the information supposed to have been transmitted could have been important, a man of Greenglass' capacity is wholly incapable of transmitting the physics, chemistry, and mathematics of the atomic bomb to anyone. After that it was difficult for us to accept, as justification of an unprecedented sentence, the following statement of Judge Kaufman: "I believe your conduct in putting into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb, has already caused the Communist aggression in Korea with the resulting casualties." The mere fact that such statements should have found their place in the text of the sentence, raised the gravest doubts in our minds as to its soundness and motivation.

Indeed the gravest, the most decisive point was the nature of the sentence itself. Even if the Rosenbergs actually performed the acts with which they were charged, we were shocked at a death sentence pronounced in time of peace, for actions committed, it is true, in time of war, but a war in which Russia was an ally, not an enemy, of the United States...

We could not understand that Ethel Rosenberg should have been sentenced to death when the specific acts of which she was accused were only two conversations; and we were unable to accept the death sentence as being justified by the "moral support" she was supposed to have given her husband. In fact the severity of the sentence, even if one provisionally accepted the validity of the Greenglass testimony, appeared out of all measure and reason to such an extent as to cast doubt on the whole affair, and to suggest that nationalistic passions and pressure from an inflamed public opinion, had been strong enough to distort the proper administration of justice.