Communist Secret Police: NKVD

In 1933, the Government Political Administration (GPU) became known as the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD). However, they also sent agents to work abroad. The United States was its main target. Valentine Markin, a senior NKVD official based in New York City sent a cable to Moscow in March 1934 that stated: "In world politics, the U.S. is the determining factor. There are no problems, even those 'purely' European, in whose solution America does not take part because of its economic and financial strength. It plays a special role in the solution of the Far Eastern problem. That is why America must be well informed in European and Far Eastern matters, and its intelligence service is likely to play an active role. This situation raises the following extremely important problems for our intelligence in the U.S... It is necessary that the agents we now have or intend to recruit provide us with documents and verified materials clarifying the U.S. position in the matters mentioned above and, especially, the U.S. position on the Far Eastern problem."

Over the next few years the NKVD had several important agents based in the United States. Vsevolod Merkulov and Pavel Fitin were put in charge of the operation. Agents based in America included Gaik Ovakimyan, Semyon Semyonov, Boris Bykov, Vassili Zarubin, Alexander Feklissov, Leonid Kvasnikov, Anatoly Gorsky, Iskhak Akhmerov, Boris Bazarov, Peter Gutzeit, Gerhart Eisler, Elizabeth Zarubina and Vassili Mironov.

Agents recruited in the United States included Cedric Belfrage, Elizabeth Bentley, Marion Bachrach, Joel Barr, Abraham Brothman, Earl Browder, Karl Hermann Brunck, Louis Budenz, Whittaker Chambers, Frank Coe, Henry Hill Collins, Lauchlin Currie, Hope Hale Davis, Samuel Dickstein, Martha Dodd, Laurence Duggan, Gerhart Eisler, Noel Field, Harold Glasser, Vivian Glassman, Jacob Golos, Theodore Hall, Alger Hiss, Donald Hiss, Joseph Katz, Charles Kramer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Harvey Matusow, Hede Massing, Paul Massing, Boris Morros, William Perl, Victor Perlo, Lee Pressman, Joszef Peter, Mary Price, William Remington, Alfred Sarant, Abraham George Silverman, Helen Silvermaster, Nathan Silvermaster, Alfred Stern, William Ludwig Ullmann, Julian Wadleigh, Harold Ware, William Weisband, Nathaniel Weyl, Donald Niven Wheeler, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Witt and Mark Zborowski.

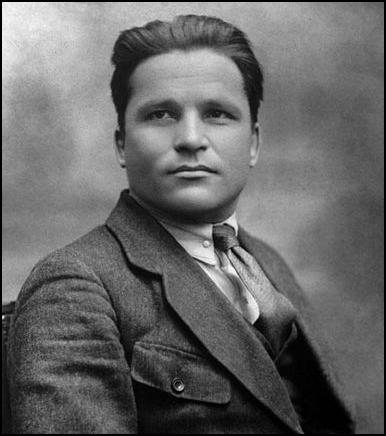

Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Yagoda, was appointed as the head of the NKVD. One of his first tasks was to remove Stalin's main rival for the leadership of the party. Sergy Kirov had been a loyal supporter of Stalin but he grew jealous of his popularity. As Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "In sharp contrast to Stalin, Kirov was a much younger man and an eloquent speaker, who was able to sway his listeners; above all, he possessed a charismatic personality. Unlike Stalin who was a Georgian, Kirov was also an ethnic Russian, which stood in his favour." According to Orlov, who had been told this by Yagoda, Stalin decided that Kirov had to die.

Yagoda assigned the task to Vania Zaporozhets, one of his trusted lieutenants in the NKVD. He selected a young man, Leonid Nikolayev, as a possible candidate. Nikolayev had recently been expelled from the Communist Party and had vowed his revenge by claiming that he intended to assassinate a leading government figure. Zaporozhets met Nikolayev and when he discovered he was of low intelligence and appeared to be a person who could be easily manipulated, he decided that he was the ideal candidate as assassin.

Zaporozhets provided him with a pistol and gave him instructions to kill Kirov in the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. However, soon after entering the building he was arrested. Zaporozhets had to use his influence to get him released. On 1st December, 1934, Nikolayev, got past the guards and was able to shoot Kirov dead. Nikolayev was immediately arrested and after being tortured by Yagoda he signed a statement saying that Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev had been the leaders of the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov.

According to Alexander Orlov, a senior figure in the NKVD: "Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov". Victor Kravchenko has pointed out: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks."

Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001), claims that Orlov later admitted: "In the months preceding the trial, the two men were subjected to every conceivable form of interrogation: subtle pressure, then periods of enormous pressure, starvation, open and veiled threats, promises, as well as physical and mental torture. Neither man would succumb to the ordeal they faced." Stalin was frustrated by Stalin's lack of success and brought in Nikolai Yezhov to carry out the interrogations.

Orlov claims that. "Towards the end of their ordeal, Zinoviev became sick and exhausted. Yezhov took advantage of the situation in a desperate attempt to get a confession. Yezhov warned that Zinoviev must affirm at a public trial that he had plotted the assassination of Stalin and other members of the Politburo. Zinoviev declined the demand. Yezhov then relayed Stalin's offer; that if he co-operated at an open trial, his life would be spared; if he did not, he would be tried in a closed military court and executed, along with all of the opposition. Zinoviev vehemently rejected Stalin's offer. Yezhov then tried the same tactics on Kamenev and again was rebuffed."

In July 1936 Yezhov told Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev that their children would be charged with being part of the conspiracy and would face execution if found guilty. The two men now agreed to co-operate at the trial if Stalin promised to spare their lives. At a meeting with Stalin, Kamenev told him that they would agree to co-operate on the condition that none of the old-line Bolsheviks who were considered the opposition and charged at the new trial would be executed, that their families would not be persecuted, and that in the future none of the former members of the opposition would be subjected to the death penalty. Stalin replied: "That goes without saying!"

Trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev

The trial opened on 19th August 1936. Five of the sixteen defendants were actually NKVD plants, whose confessional testimony was expected to solidify the state's case by exposing Zinoviev, Kamenev and the other defendants as their fellow conspirators. The presiding judge was Vasily Ulrikh, a member of the secret police. The prosecutor was Andrei Vyshinsky, who was to become well-known during the Show Trials over the next few years.

Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Kamenev's final words in the trial concerned the plight of his children: "I should like to say a few words to my children. I have two children, one is an army pilot, the other a Young Pioneer. Whatever my sentence may be, I consider it just... Together with the people, follow where Stalin leads." This was a reference to the promise that Stalin made about his sons.

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh entered the courtroom and began reading the long and dull summation leading up to the verdict. Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "Those in attendance fully expected the customary addendum which was used in political trials that stipulated that the sentence was commuted by reason of a defendant's contribution to the Revolution. These words never came, and it was apparent that the death sentence was final when Ulrikh placed the summation on his desk and left the court-room."

The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death. This included the NKVD agents who had provided false confessions. Joseph Stalin could not afford for any witnesses to the conspiracy to remain alive. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out that Stalin did not even keep his promise to Kamenev's sons and later both men were shot.

Nikolai Yezhov

Joseph Stalin became angry with Genrikh Yagoda when he failed to obtain enough evidence to convict Nickolai Bukharin. In September, 1936, Nikolai Yezhov replaced Yagoda as head of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD). Yezhov quickly arranged the arrest of all the leading political figures in the Soviet Union who were critical of Stalin. Boris Nicolaevsky was one of Stalin's opponents who managed to escape from the Soviet Union. He later recalled: "In the whole of my long life, I have never met a more repellent personality than Yezhov's. When I look at him I am reminded irresistibly of the wicked urchins of the courts in Rasterayeva Street, whose favorite occupation was to tie a piece of paper dipped in kerosene to a cat's tail, set fire to it, and then watch with delight how the terrified animal would tear down the street, trying desperately but in vain to escape the approaching flames. I do not doubt that in his childhood Yezhov amused himself in just such a manner and that he is now continuing to do so in different forms."

According to Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996): "Yezhov was typical of those who rose from nowhere to high positions in this period: semiliterate, obedient, and hardworking. His dubious past made him particularly eager to shine. Most important of all - he had made his career after the overthrow of the October leaders. Yagoda now served Stalin, but until recently had been the servant of the Party. Yezhov had served no-one but Stalin. He was the man to implement the second half of Stalin's scheme. For him there were no taboos. At the height of the Terror Yezhov would be portrayed on thousands of posters as a giant in whose hands enemies of the people writhed and breathed their last... Yezhov was merely a pseudonym for Stalin himself, a pathetic puppet, there simply to carry out orders. All the thinking was done, all the decisions were made, by the Boss himself."

Nadezhda Khazina and her husband, Osip Mandelstam, met him after his appointment: "In the period of the Yezhov terror - the mass arrests came in waves of varying intensity - there must sometimes have been no more room in the jails, and to those of us still free it looked as though the highest wave had passed and the terror was abating... We first met Yezhov in the 1930s when Mandelstam and I were staying in a Government villa in Sukhumi. It is hard to credit that we sat at the same table, eating, drinking and exchanging small talk with this man who was to be one of the great killers of our time, and who totally exposed - not in theory but in practice - all the assumptions on which our humanism rested.... Yezhov was a modest and rather agreeable person. He was not yet used to being driven about in an automobile and did not therefore regard it as an exclusive privilege to which no ordinary mortal could lay claim. We sometimes asked him to get him to get a lift into town, and he never refused."

Eugene Lyons worked as a journalist in Moscow. He wrote about his experiences in his autobiography, Assignment in Utopia (1937): "One need not be guilty of an overt act to have his house searched, himself stuck away in a foul cell, his family terrorized. An anonymous denunciation by someone who coveted his room or his job might do it, or the fact that he had been seen playing chess with someone else who was denounced. Perhaps his name was listed in the address book of a suspected person, or a second cousin by marriage, in the course of interrogation, had mentioned the relationship... I knew dozens of men and women who lived in a state of chronic terror, their little suitcases always packed, though they worked diligently and avoided even facial expressions which might cast doubt on their loyalty. To awaken in their own beds in the morning was a daily miracle for such people. The sound of a doorbell at an unusual hour left them limp and trembling."

In August 1936 Alexander Orlov was appointed by the Soviet Politburo as adviser to the Popular Front government in Spain. Orlov was given considerable authority by the Republican administration during the Spanish Civil War. Orlov supervised a large-scale guerrilla operation behind Nationalist lines. He later claimed that around 14,000 people had been trained for this work by 1938. Orlov also used NKVD agents to deal with left-wing opponents of the Communist Party (PCE) in Republican held areas. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of the Worker's Party (POUM), National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI).

Administration of Special Tasks

In December 1936, Nikolai Yezhov established a new section of the NKVD named the Administration of Special Tasks (AST). It contained about 300 of his own trusted men from the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Yezhov's intention was complete control of the NKVD by using men who could be expected to carry out sensitive assignments without any reservations. The new AST operatives would have no allegiance to any members of the old NKVD and would therefore have no reason not to carry out an assignment against any of one of them. The AST was used to remove all those who had knowledge of the conspiracy to destroy Stalin's rivals. One of the first to be arrested was Genrikh Yagoda, the former head of the NKVD.

Within the administration of the ADT, a clandestine unit called the Mobile Groups had been created to deal with the ever increasing problem of possible NKVD defectors, as officers serving abroad were beginning to see that the arrest of people like Yagoda, their former chief, would mean that they might be next in line. By the summer of 1937, an alarming number of intelligence agents serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union. Most of those, including Theodore Mally, were executed.

Ignaz Reiss was an NKVD agent serving in Belgium when he was summoned back to the Soviet Union. Reiss had the advantage of having his wife and daughter with him when he decided to defect to France. In July 1937 he sent a letter to the Soviet Embassy in Paris explaining his decision to break with the Soviet Union because he no longer supported the views of Stalin's counter-revolution and wanted to return to the freedom and teachings of Lenin. Orlov learnt of this letter from a close contact in France.

According to Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001): "On learning that Reiss had disobeyed the order to return and intended to defect, an enraged Stalin ordered that an example be made of his case so as to warn other KGB officers against taking steps in the same direction. Stalin reasoned that any betrayal by KGB officers would not only expose the entire operation, but would succeed in placing the most dangerous secrets of the KGB's spy networks in the hands of the enemy's intelligence services. Stalin ordered Yezhov to dispatch a Mobile Group to find and assassinate Reiss and his family in a manner that would be sure to send an unmistakable message to any KGB officer considering Reiss's route."

Reiss was found hiding in a village near Lausanne, Switzerland. It was claimed by Alexander Orlov that a trusted Reiss family friend, Gertrude Schildback, lured Reiss to a rendezvous, where the Mobile Group killed Reiss with machine-gun fire on the evening of 4th September 1937. Schildback was arrested by the local police and at the hotel was a box of chocolates containing strychnine. It is believed these were intended for Reiss's wife and daughter.

By the beginning of 1938, most of the intelligence officers serving abroad had been targeted for elimination had already returned to Moscow. Joseph Stalin now decided to remove another witness to his crimes, Abram Slutsky. On 17th February 1938, Slutsky was summoned to the office of Mikhail Frinovsky, one of those who worked closely with Nikolai Yezhov, the head of ADT. According to Mikhail Shpiegelglass he was called to Frinovsky's office and found him dead from a heart attack.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, the author of Stalin: The Count of the Red Tsar (2004): "Yezhov was called upon to kill his own NKVD appointees whom he had protected. In early 1938, Stalin and Yezhov decided to liquidate the veteran Chekist, Abram Slutsky, but since he headed the Foreign Department, they devised a plan so as not to scare their foreign agents. On 17 February, Frinovsky invited Slutsky to his office where another of Yezhov's deputies came up behind him and drew a mask of chloroform over his face. He was then injected with poison and died right there in the office. It was officially announced that he had died of a heart attack." Two months later Slutsky was posthumously stripped of his CPSU membership and declared an enemy of the people.

Under Nikolai Yezhov, the Great Purge increased in intensity. In 1937 Yezhov arranged the arrest of Genrikh Yagoda, the former head of the NKVD. He was charged with Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky of being involved with Leon Trotsky in a plot against Joseph Stalin. They were all found guilty and were eventually executed. It is estimated that over the next year it is estimated that 1.3 million were arrested and 681,692 were shot for "crimes against the state". According to the historian, Emil Draitser, "during 1937 and 1938, 681,692 prisoners (353,074 and 328,618, respectively) received death sentences (nearly 1,000 per day)."

Purge of Red Army

Stalin became convinced that the leaders of the Red Army were involved in a plot to overthrow him. In June, 1937, Mikhail Tukhachevsky and seven other top commanders were charged with conspiracy with Germany. William Stephenson, head of the British Security Coordination (BSC), who was aware of what was going on later pointed out: "Late in 1936, Heydrich had thirty-two documents forged to play on Stalin's sick suspicions and make him decapitate his own armed forces. The Nazi forgeries were incredibly successful. More than half the Russian officer corps, some 35,000 experienced men, were executed or banished. The Soviet chief of Staff, Marshal Tukhachevsky, was depicted as having been in regular correspondence with German military commanders. All the letters were Nazi forgeries. But Stalin took them as proof that even Tukhachevsky was spying for Germany. It was a most devastating and clever end to the Russo-German military agreement, and it left the Soviet Union in absolutely no condition to fight a major war with Hitler." Tukhachevsky was found guilty and executed on 11th June, 1937. It is estimated that 30,000 members of the armed forces were killed. This included fifty per cent of all army officers.

Lavrenty Beria

Joseph Stalin told Yezhov that he needed some help in running the NKVD and asked him to choose someone. Yezhov requested Georgy Malenkov but Stalin wanted to keep him in the Central Committee and sent him Lavrenty Beria instead. Simon Sebag Montefiore commented: "Stalin may have wanted a Caucasian, perhaps convinced that the cut-throat traditions of the mountains - blood feuds, vendettas and secret murders - suited the position. Beria was a natural, the only First Secretary who personally tortured his victims. The blackjack - the zhgtrti - and the truncheon - the dubenka - were his favourite toys. He was hated by many of the Old Bolsheviks and family members around the leader. With the whispering, plotting and vengeful Beria at his side, Stalin felt able to destroy his own polluted, intimate world."

Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004) has argued: "Yezhov understood the danger he was in and his daily routine became hectic; he knew that the slightest mistake could prove fatal. Somehow, though, he had to show himself to Stalin as indispensable. Meanwhile he also had to cope with the appointment of a new NKVD Deputy Commissar, the ambitious Lavrenti Beria, from July 1938. Beria had until then been First Secretary of the Communist Party of Georgia; he was widely feared in the south Caucasus as a devious plotter against any rival - and almost certainly he had poisoned one of them, the Abkhazian communist leader Nestor Lakoba, in December 1936. If Yezhov tripped, Beria was ready to take his place; indeed Beria would be more than happy to trip Yezhov up. Daily collaboration with Beria was like being tied in a sack with a wild beast. The strain on Yezhov became intolerable. He took to drinking heavily and turned for solace to one-night stands with women he came across; and when this failed to satiate his needs, he pushed himself upon men he encountered in the office or at home. In so far as he was able to secure his future position, he started to gather compromising material on Stalin himself.... On 17 November the Politburo decided that enemies of the people had infiltrated the NKVD. Such measures spelled doom for Yezhov. He drank more heavily. He turned to more boyfriends for sexual gratification."

On 23rd November 1938, Lavrenty Beria replaced Yezhov as head of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD). Yezhov was arrested on 10th April, 1939. It is claimed by the authors of Stalin's Loyal Executioner (2002) that Yezhov quickly confessed under torture to being an "enemy of the people". This included a confession that he was an homosexual.

Of the 1,966 delegates that attended the Communist Party Congress in 1934, 1,108 were arrested over the next five years. Only seventy people were tried in public. The rest were tried in secret before being executed. Official figures suggest that between January 1935 and June 1941, 19.8 million people were arrested by the NKVD. An estimated seven million of these prisoners were executed.

With the murder of Leon Trotsky in 20th August, 1940, all the leading figures involved in the Russian Revolution were dead except for Joseph Stalin. Of the fifteen members of the original Bolshevik government, ten had been executed and four had died (sometimes in mysterious circumstances). The armed forces suffered at the hands of Beria and the NKVD. It has been estimated that a third of all officers were arrested. Three out of five marshals and fourteen out of sixteen army commanders were executed.

After the Second World War the Communist Secret Police was renamed the Committee for State Security (KGB).

Primary Sources

(1) In 1933 Victor Serge was taken to the headquarters of the Communist Secret Police.

It was a prison of noiseless, cell-divided secrecy, built barely into a block that had once been occupied by insurance company offices. Each floor formed a prison on its own, sealed off from the others, with its individual entrance and reception-kiosk; coloured electric light-signals operated on all landings and corridors to mark the various comings and goings, so that prisoners could never meet one another. A mysterious hotel-corridor, whose red carpet silenced the slight sound of footsteps; and then a cell, bare, with an inlaid floor, a passable bed, a table and a chair, all spick and span.

Here, in absolute secrecy, with no communication with any person whatsoever, with no reading-matter whatsoever, with no paper, not even one sheet, with no occupation of any kind, with no open-air exercise in the yard, I spent about eighty days. It was a severe test for the nerves, in which I acquitted myself pretty well. I was weary with my years of nervous tension, and felt an immense physical need for rest. I slept as much as I could, at least twelve hours a day. The rest of the time, I set myself to work assiduously. I gave myself courses in history, political economy - and even in natural science! I mentally wrote a play, short stories, poems.

(2) Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (1937)

One need not be guilty of an overt act to have his house searched, himself stuck away in a foul cell, his family terrorized. An anonymous denunciation by someone who coveted his room or his job might do it, or the fact that he had been seen playing chess with someone else who was denounced. Perhaps his name was listed in the address book of a suspected person, or a second cousin by marriage, in the course of interrogation, had mentioned the relationship. Worst of all, the German machines he had helped buy or install, after being manhandled by peasants accustomed only to managing wooden plows, had broken down mysteriously.

Those who remember the war-time atmosphere, in which everyone detected spies in his neighbors and the intelligence divisions in all countries were deluged with denunciations, can appreciate the ordeal of the technical and managerial forces in the Russia of the Piatiletka. The engineer or administrator was the obvious scapegoat for promises that could not be kept, for plans that went askew. He was punished for "underestimating (or overestimating) the possibilities" of his particular enterprise, for risking (or shirking) a crucial technical decision.

The G.P.U. agent, reckoning his usefulness by the number of "confessions" he extracted, was hardly fitted to trace the tenuous borderline where inefficiency or sheer carelessness ended and sabotage began. The arrested intellectual himself was no longer able to locate that border-line after being held incommunicado for months, aware that his relatives were in danger, confronted with "confessions" by colleagues implicating him, and conscious also of his deeper inner disapproval of the Bolshevik ideology. One can understand how men signed "confessions" filled with impossible detail. The hysteria sucked accusers and accused alike into the maelstrom of its lunacy.

I knew dozens of men and women who lived in a state of chronic terror, their little suitcases always packed, though they worked diligently and avoided even facial expressions which might cast doubt on their loyalty. To awaken in their own beds in the morning was a daily miracle for such people. The sound of a doorbell at an unusual hour left them limp and trembling.

The roster of scientists, historians, Academicians, famous engineers, technical administrators, statisticians arrested at this time reads like an encyclopedia of contemporary Russian culture. Many of them were held for months, for years, without so much as discovering the mysterious crimes charged against them. In addition to almost unlimited raw labor, the G.P.U. now had an unlimited supply of technical brains at its disposal.

The revolt against intelligence, signalized in the new personnel of the Politburo, held true in the whole life of the USSR. Distrust of the educated man or woman was magnified endlessly by the disappointments, the despairs, the bitterness of a hundred and sixty million individuals.

(3) Rutkovsky was one of the members of the Communist Secret Police (GPU) who interviewed Victor Serge in 1933. He attempted to get Serge to sign a confession agreeing that he had worked with Anita Russakova against the Soviet government. Serge knew that once he signed a confession he would be executed.

I can see that you are an unwavering enemy. You are bent on destroying yourself. Years of jail are in store for you. You are the ringleader of the Trotskyite conspiracy. We know everything. I want to try and save you in spite of yourself. This is the last time that we try. So, I'm making one last attempt to save you.

I don't expect very much from you - I know you too well. I am going to acquaint you with the complete confessions that have been made by your sister-in-law and secretary, Anita Russakova. All you have to do it say, "I admit that it is true", and sign it. I won't ask you any more questions, the investigation will be closed, your whole position will be improved, and I shall make every effort to get the Collegium to be lenient to you.

(4) Alexander Orlov was a NKVD officer who escaped to the United States.

Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov, "the beloved son of the party", a member of the Politburo, he then would be justified in demanding blood for blood.

(5) The New Republic (9th January, 1935)

Up to last Sunday 117 persons had been executed in Soviet Russia as the direct result of the Kirov assassination. To what extent are Zinoviev and Kamenev implicated in the plot. The hysteria of Karl Radek's and Nikolai Bukharin's charges against them in Pravda and Izvestia fails to carry conviction.

Russia's right to crush Nazi-White Guard conspiracies or other plots of murder and arson no one questions; few have anything but approval for it. What is in question is the guilt of particular persons who have not been tried in an open court of law.

(6) Victor Kravchenko, I Choose Freedom (1947)

Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks. Almost hourly the circle of those supposedly implicated, directly or "morally", was widened until it embraced anyone and everyone who had ever raised a doubt about any Stalinist policy.

(7) Gregory Zinoviev, speech at his trial (August, 1936)

I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky.

(8) Lev Kamenev, speech at his trial (August, 1936)

I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organized and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power.

(9) The New Republic (2nd September, 1936)

Some commentators, writing at a long distance from the scene, profess doubt that the executed men (Zinoviev and Kamenev) were guilty. It is suggested that they may have participated in a piece of stage play for the sake of friends or members of their families, held by the Soviet government as hostages and to be set free in exchange for this sacrifice. We see no reason to accept any of these laboured hypotheses, or to take the trial in other than its face value. Foreign correspondents present at the trial pointed out that the stories of these sixteen defendants, covering a series of complicated happenings over nearly five years, corroborated each other to an extent that would be quite impossible if they were not substantially true. The defendants gave no evidence of having been coached, parroting confessions painfully memorized in advance, or of being under any sort of duress.

(10) The New Statesman (5th September, 1936)

Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation.

(11) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

And on 14 August, like a thunderbolt, came the announcement of the Trial of the Sixteen, concluded on the 25th - eleven days later - by the execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev, Ivan Smirnov, and all their fellow-defendants. I understood, and wrote at once, that this marked the beginning of the extermination of all the old revolutionary generation. It was impossible to murder only some, and allow the others to live, their brothers, impotent witnesses maybe, but witnesses who understood what was going on.

(12) Nikolay Krestinsky, speech at his trial (12th March, 1938)

I do not recognize that I am guilty. I am not a Trotskyite. I was never a member of the "right-winger and Trotskyite bloc", which I did not know to exist. Nor have I committed a single one of the crimes imputed to me, personally; and in particular I am not guilty of having maintained relations with the German Secret Service.

(13) Nikolay Krestinsky, speech at his trial (13th March, 1938)

Yesterday, a passing but sharp impulse of false shame, created by these surroundings and by the fact that I am on trial, and also by the harsh impression made by the list of charges and by my state of health, prevented me from telling the truth, from saying that I was guilty. And instead of saying "Yes, I am guilty", I replied, almost by reflex, "No I am not guilty."

(14) Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (1937)

The basic mechanism and chief reliance of the extortion artists were physical torture. In every city the Valuta Department might develop its own sadistic specialties, but apparently several basic techniques were common to them all.

The parilka, or sweat room, has been described to me so often that I feel as though I had seen it with my own eyes. I can see it now with my mind's eye. Several hundred men and women, standing close-packed in a small room where all ventilation has been shut off, in heat that chokes and suffocates, in stink that asphyxiates, one small bulb shedding a dim light on the purgatory. Many of them have stood thus for a day, for two days. Most of them have ripped their clothes off in fighting the heat and the sweat and the swarming lice that feed upon them. Their feet are swollen, their bodies numbed and aching. They are not allowed to sit down or to squat. They lean against one another for support, sway with one rhythm and groan with one voice. Every now and then the door is opened and a newcomer is squeezed in. Every now and then those who have fainted are dragged out into the corridor, revived and thrown back into the sweat room ... sometimes they cannot be revived.

The so-called "conveyor" has been graphically described by Professor Tchernavin in his book, I Speak for the Silent. His description coincides substantially with the accounts I have heard myself from victims who had been through the torture. Examiners sit at desks in a long series of rooms, strung out along corridors, up and down stairways, back to the starting point: a sort of circle of G.P.U. agents. The victims run at a trot from one desk to the next, cursed, threatened, insulted, bullied, questioned by each agent in turn, round and round, hour after hour. They weep and plead and deny and keep running... If they fall they are kicked and beaten on their shins, stagger to their feet and resume the hellish relay. The agents, relieved at frequent intervals, are always fresh and keen, while the victims grow weaker, more terrorized, more degraded.

From the parilka to the conveyor, from the conveyor to the parilka, then periods in ugly cells when uncertainty and fear for one's loved ones outside demoralize the prisoner ...weeks of this while the "hidden valuta resources" are being "mobilized" by the G.P.U. in a thousand cities of the socialist fatherland. I am aware of my impotence to translate more than a hint of the Gehenna into words. One must hear it from the mouth of a haggard, feverish victim fresh from the ordeal to grasp the hellishness of it.

If physical torture failed to break down someone... members of his family were brought in and tortured under his eyes. I heard the detailed story of a former merchant who insisted for weeks that he had nothing, absolutely nothing left. Only when one of his children, a little boy, was thrown into the Parilka with him and kept there for three days did he remind himself that he did have a box of jewels buried in his back yard. Then another child was brought for torture, and he admitted to more valuta in another hiding place. His whole family was on the rack before he was stripped clean of his surreptitious wealth.

A Russian-American businessman came as a tourist to visit his aged parents in Kiev. For years he had been sending them a monthly remittance, which was their only support. Completely distressed by the squalid poverty in which his father and mother lived, he tried in vain to arrange for them to leave the country; this was before the valuta ransom racket was inaugurated. He did the next best thing and found them a better room to live in by paying American dollars to the trust which controlled the tenement house. He outfitted them at Torgsin and paid for large stocks of food. And before departing he left them four or five hundred dollars in cash.

That gift was tantamount to a sentence of torture for the father. No sooner had his son left than the old man was dragged away to the torture chambers. He immediately relinquished the few hundred dollars. The very alacrity with which he did it convinced the a(rents that it could not be all, that he must have more than he admitted. (Seasoned victims knew the danger of yielding too soon and thereby exciting the doubts and cupidity of their tormentors; one victim warned another to take the medicine of torture before capitulatina if he wanted to be believed.) So he was taken in custody at regular intervals for another installment of "persuasion."

A routine practice was to force Soviet citizens to write to relatives abroad begging for large sums of money. The letters, dictated by the G.P.U., usually made frantic appeals for specified amounts, explaining vaguely that it was "a matter of life and death." When the money arrived, it was, of course, instantly "contributed" to the Five Year Plan. Jews in particular were subjected to this racket on the theory that blood ties are strong in Jewish families and a tragic plea for cash would not be ignored by well-off American sons and uncles.

(15) Indictment against Pantelei Yefimovich Gopkalo (grandfather of Mikhail Gorbachev) in 1938.

(a) He impeded harvesting operations and thus created conditions for the loss of grain. Pursuing the destruction of the kolkhoz livestock he artificially reduced the fodder base by ploughing up meadows which resulted in kolkhoz cattle starving;

(b) He obstructed the progress of the Stakhanovite movement in the kolkhoz by repressing Stakhanovites. On the basis of the facts stated heretofore he is charged with anti-Soviet activities: being an enemy of the CPSU (B) and of the Soviet system and having established ties with the members of an abolished anti-Soviet right-wing Trotskyist organization, he carried out their instructions of subversive acts at the 'Red October' kolkhoz which were aimed at undermining the economic well-being of the kolkhoz.

(16) NKVD Secret Police report on Mikhail Gorbachev's grandfather's interrogation in 1938.

"You have been arrested on the charge of being a member of a counter-revolutionary right-wing Trotskyist organization. Do you plead guilty?"

"I do not plead guilty. I have never been a member of a counterrevolutionary organization."

"You're not telling the truth. The prosecution has at its disposal precise information about your membership of a counterrevolutionary right-wing Trotskyist organization. Give us truthful evidence in the case."

"I repeat, I have not been a member of a counterrevolutionary organization."

"You are lying. A number of people charged in this case testified against you, corroborating your counterrevolutionary activity. The prosecution insists on obtaining truthful evidence."

"I deny the accusations categorically. I don't know of any counterrevolutionary organization."