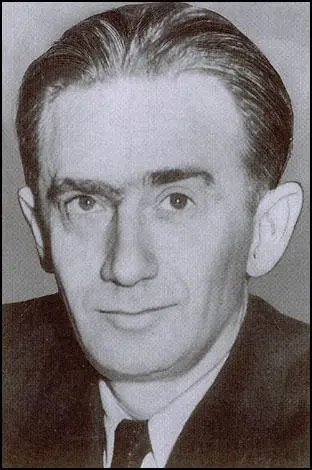

Mark Zborowski

Mark Zborowski, one of four children born into a Jewish family in Uman, in Ukraine, on 27th January, 1908. His family disapproved of the Russian Revolution and moved to Poland in 1921.

Zborowski developed radical political opinions while a student and joined the Polish Communist Party. He was arrested and imprisoned but when he was released he moved to Berlin. Later he attended the University of Grenoble where he studied anthropology.

In 1933 Zborowski moved to Paris. While working as a waiter he was recruited by the NKVD. He served under Mikhail Shpiegelglass who was the head of the Administration of Special Tasks (AST), an assassination unit based in Europe. According to historian John J. Dziak, the author of Chekisty: A History of the KGB (1987), Zborowski, using the name Etienne, worked with Nikolai Skoblin and was involved in the murders of Ignaz Reiss and Andrés Nin. Zborowski was ordered to infiltrate the group based in France that supported Leon Trotsky and produced the Bulletin of the Opposition. He became a close friend of Victor Serge who brought him to a meeting with Elsa Poretsky and Henricus Sneevliet. Elsa, whose husband had worked for the NKVD, was immediately suspicious of his story that he had been able to escape from the Soviet Union. Another agent, Walter Krivitsky, had told her: "No one leaves the Soviet Union unless the NKVD can use him". Zbrowski began working for Trotsky's son, Lev Sedov. According to Robert Service, the author of Trotsky (2009), some of the group were highly suspicious of Zborowski: "His story was that he was a committed Trotskyist from Ukraine who had travelled to France in 1933 to offer his services. He retained Lev's complete confidence despite the reservations expressed by French comrades. Etienne aimed to become indispensable to Lev, and he succeeded. Cool-headed and assiduous, he relieved Lev of many tasks in a heavy workload. Not everyone took to him. It was far from clear where he got his money from or even how he managed to subsist. Lev's secretary Lola Estrina sympathetically invented jobs for him to do and paid him each time he did one of them. A routine was established: Etienne worked alongside Lev in the mornings and Lola took his place in the afternoons. Equipped by his handlers with a camera, Etienne photographed items in the organization's files.... Etienne's growing prominence in this situation gave rise to suspicions among French Trotskyists." Pierre Naville mentioned his worries to Trotsky, who retorted: "You want to deprive me of my collaborators." Joseph Stalin became extremely angry with Sedov when he published the The Red Book in 1936. In the book, he produced a critical analysis of Stalinism. "The old petit-bourgeois family is being reestablished and idealized in the most middle-class way; despite the general protestations, abortions are prohibited, which, given the difficult material conditions and the primitive state of culture and hygiene, means the enslavement of women, that is, the return to pre-October times. The decree of the October revolution concerning new schools has been annulled. School has been reformed on the model of tsarist Russia: uniforms have been reintroduced for the students, not only to shackle their independence, but also to facilitate their surveillance outside of school. Students are evaluated according to their marks for behavior, and these favor the docile, servile student, not the lively and independent schoolboy.... A whole institute of inspectors has been created to look after the behavior and morality of the youth." Sedov went onto argue that Stalin was sending a message to the world that he had abandoned the Marxist concept of Permanent Revolution: "Stalin not only bloodily breaks with Bolshevism, with all its traditions and its past, he is also trying to drag Bolshevism and the October revolution through the mud. And he is doing it in the interests of world and domestic reaction.... The corpses of the old Bolsheviks must prove to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has in reality radically changed his politics, that the men who entered history as the leaders of revolutionary Bolshevism, the enemies of the bourgeoisie - are his enemies also.... They (the Bolsheviks) are being shot and the bourgeoisie of the world must see in this the symbol of a new period. This is the end of the revolution, says Stalin. The world bourgeoisie can and must reckon with Stalin as a serious ally, as the head of a nation-state. Such is the fundamental goal of the trials in the area of foreign policy. But this is not all, it is far from all. The German fascists who cry that the struggle against communism is their historic mission find themselves most recently in a manifestly difficult position. Stalin has abandoned long ago the course toward world revolution." In November 1936, Zborowsky helped a team of Soviet agents to plunder the Leon Trotsky archives from the a Nikolayevsky Institute. The director of the Institute was Boris Nikolaevski. He was a devoted collector of all material that shed light on Russian revolutionary history and Lev Sedov had decided that his father's files would be safest in his care. The burglars left no sign of breakage on entry. Everyone suspected the NKVD but no one knew how the crime had been planned and undertaken. Zborowsky's reports, which were apparently read personally by Stalin, increased his fear of Lev Sedov. Zborowsky claims that on 22nd January, 1937, while discussing the Show Trials in Moscow, Sedov said: "Now we shouldn't hesitate. Stalin should be murdered." John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, the authors of Deadly Illusions (1993), finds this difficult to believe: "Zborowsky's unsubstantiated reports that Trotsky and Sedov were contemplating the assassination of Stalin is contrary to all their public pronouncements and the evidence contained in Trotsky's private papers that were examined by the international commission. That it appears at all in the NKVD files is significant. Even its veracity is open to question and what Zborowsky reported may have been merely an emotional outburst rather than any practical plan and it could have been pure invention to please Stalin." Abram Slutsky now grew very suspicious of Walter Krivitsky and insisted that he turned over his spy-ring to Mikhail Shpiegelglass. This included his second in command, Hans Brusse. Soon afterwards, Brusse made contact with Krivitsky and told him that Shpiegelglass had ordered him to kill Elsa Poretsky and her son. Krivitsky advised him to accept the mission, but to sabotage the operation. Krivitsky also suggested that Brusse should gradually withdraw from working for the NKVD. According to Krivitsky's account in I Was Stalin's Agent (1939), Brusse agreed to this strategy. After the assassination of Ignaz Reiss, Krivitsky discovered that Theodore Maly, who had refused to kill him, was recalled and executed. He now decided to defect to Canada. Once settled abroad he would collaborate with Paul Wohl on the literary projects they had so often discussed. In addition to writing about economic and historical subjects, he would be free to comment on developments in the Soviet Union. Wohl agreed to the proposal. He told Krivitsky that he was an exceptional man with rare intelligence and rare experience. He assured him that there was no doubt that together they could succeed. Wohl agreed to help Krivitsky defect. To help him disappear he rented a villa for him in Hyères, a small town in France on the Mediterranean Sea. On 6th October, 1937, Wohl arranged for a car to collect Krivitsky, Antonina Porfirieva and their son and to take them to Dijon. From there they took a train to their new hideout on the Côte d'Azur. As soon as he discovered that Krivitsky had fled, Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Nikolai Yezhov what had happened. After he received the report, Yezhov sent back the command to assassinate Krivitsky and his family. Later that month Krivitsky wrote to Elsa Poretsky and told her what he had done and to express concerns that the NKVD had a spy close to her friend, Henricus Sneevliet. "Dear Elsa, I have broken with the Firm and am here with my family. After a while I will find the way to you, but right now I beg you not to tell anyone, not even your closest friends, who this letter is from... Listen well, Elsa, your life and that of your child are in danger. You must be very careful. Tell Sneevliet that in his immediate vicinity informers are at work, apparently also in Paris among the people with whom he has to deal. He should be very attentive to your and your child's welfare. We both are completely with you in your grief and embrace you." He gave the letter to Gerard Rosenthal, who took it to Sneevliet who passed it onto Poretsky. On 7th November, 1937, Walter Krivitsky returned to Paris where Paul Wohl arranged for him to meet Lev Sedov, the son of Leon Trotsky, and the leader of the Left Opposition in France an editor of the Bulletin of the Opposition. Sedov put him in touch with Fedor Dan, who had a good relationship with Leon Blum, the leader of the French Socialist Party and a member of the Popular Front government. Although it took several weeks, Krivitsky received French papers and if needed, a police guard. Krivitsky also arranged a meeting with Hans Brusse who he hoped to persuade him to defect. Brusse refused declaring that he had come to the meeting "in the name of the organization". He then pulled out a copy of Krivitsky's letter to Elsa. Krivitsky was deeply shocked, but denied having written the letter. He suspected that he knew he was lying. Brusse pleaded with Krivitsky to return to his work as a Soviet spy. On 11th November, 1937, Walter Krivitsky had a meeting with Elsa Poretsky, Henricus Sneevliet, Pierre Naville and Gerard Rosenthal. Poretsky later recalled in Our Own People (1969) that Krivitsky said to her: "I come to warn you that you and your child are in grave danger. I came in the hope that I could be of some help." She replied: "Your warning comes too late. Had you done this in time Ignaz would be alive now, here with us... If you had joined him, as you said you would and as he expected, he would be alive and you would be in a different position." Krivitsky, visibly shocked by her response, said: "Of all that has happened to me this is the hardest blow." Krivitsky then told the group that Brusse had showed him the letter that he had sent to Poretsky. He asked Rosenthal if he had showed the letter to anyone before giving it to Sneevliet. He admitted that he had asked Victor Serge to post the letter. He later admitted to Sneevliet that he had also shown it to Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky knew that one of these people had given a copy of the letter to Brusse, who had remained loyal to the NKVD. Krivitsky took the view that the likely candidate was Zborowski. Victor Serge has pointed out that towards the end of 1937 Lev Sedov suffered from ill health. "For several months Sedov had been complaining of various indispositions, in particular of a rather high temperature in the evenings. He wasn’t able to stand up to such ill-health. He had been leading a hard life, every hour taken up by resistance to the most extensive and sinister intrigues of contemporary history – those of a regime of foul terror born out of the dictatorship of the proletariat. It was obvious that his physical strength was exhausted. His spirits were good, the indestructible spirits of a young revolutionary for whom socialist activity is not an optional extra but his very reason for living, and who has committed himself in an age of defeat and demoralisation, without illusions and like a man." Lev Sedov had severe stomach pains. On 9th February, he was taken by Mark Zborowski to the Bergere Clinic, a small establishment run by Russian émigrés connected with the Union for Repatriation of Russians Abroad in Paris. Sedov had a operation for appendicitis that evening. It was claimed that the operation was successful and was making a good recovery. However, according to Bertrand M. Patenaude, the author of Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009): "The patient appeared to be recuperating well, until the night of 13-14 February, when he was seen wandering the unattended corridors, half-naked and raving in Russian. He was discovered in the morning lying on a bed in a nearby office, critically ill. His bed and his room were soiled with excrement. A second operation was performed on the evening of 15 February, but after enduring hours of agonizing pain, the patient died the following morning." Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001) has argued that Alexander Orlov believed he was murdered: "What concerned Orlov greatly was the fact that the hospital Sedov had been taken to, and where he expired, was the small clinic of Professor Bergere in Paris. Exactly a year earlier, Orlov had been in the same clinic because of his car accident while at the front. He had been cared for at the Bergere Clinic because it was a hospital that was trusted by the KGB to take care of high-ranking Soviet officials. Professor Bergere and his staff were sympathetic towards the Communist cause and under the influence of the KGB. Orlov was in Spain at the time of Sedov's death and was unable to ascertain the complete facts, but speculated that at the moment the KGB Centre had been apprised of the circumstances by Mark, the decision had been made to take advantage of the situation and eliminate Sedov. The autopsy performed by the KGB hirelings had to have been bogus to conceal the true cause of death." Leon Trotsky was devastated by the death of his eldest son. In a press release on 18th February he stated: "He was not only my son but my best friend." Trotsky received information from several sources that Mark Zborowski was an NKVD agent. He asked Rudolf Klement to carry out an investigation of Zborowski. According to Gary Kern "Klement put together a file and planned to take it to Brussels on July 14, where he would circulate it among various branches of the Opposition. But no one in Brussels ever saw him." Trotsky and several other members of the Left Opposition received a typewritten letter announcing that Klement had broken with the organization because of "Trotsky's Nazi connections". The Trotskyists concluded that the letters had been written under compulsion and that he was a captive of the NKVD. About a week later his headless body was discovered floating in the Seine. As a result of peculiar scars and marks on the body, it was identified as that of Klement. Walter Krivitsky an NKVD agent, told Trotsky that both Rudolf Klement and Lev Sedov had been murdered by the Russian Secret Police. Edward P. Gazur, interviewed Alexander Orlov about the case. He later pointed out: "According to Orlov, the Klement letter to Trotsky was a KGB forgery designed to make it appear that, after the denunciation, Klement had disappeared for his own reasons. Years later, Orlov would learn that... the letter was a KGB forgery and that the KGB was responsible for kidnapping and then assassinating Klement." Lilia Estrin was with Trotsky in Mexico in 1939 when he received an anonymous letter warning him that a spy named Mark had infiltrated the Parisian group. The only person of that name was Zborowski. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "Both of them discounted it because other letters (probably sent by the NKVD) had warned Trotsky against other intimates of his circle, including Lilia.... He realized that he could not spend all of his time investigating every member of his staff, yet failure to do so would leave him defenseless against infiltration. Even though he believed that his son had been murdered by the NKVD, he refused to act on the letter; Lilia returned to Paris and told Zborowski all about it." Lilia discovered several years later that the letter had come from Alexander Orlov. Zborowski fled to the United States following the invasion of France in May 1940. He arrived in New York City in 1941 and immediately made contact with David Dallin and his wife Lilia Estrin. They helped him find employment at a factory in Brooklyn and set him up in an apartment. A few months later he moved to a more expensive home at 201 West 108th Street, where the Dallins also lived. It was later discovered that the NKVD were paying Zborowski to spy on the Dallins. In 1944 he helped with the search for Victor Kravchenko who had defected to the United States. In 1954, Dallin had a meeting with Alexander Orlov. He wanted advice on a book he was writing. During the conversation Orlov asked Dallin if he knew "Mark, the agent provocateur" who was a member of the Left Opposition on Paris in the 1930s? Orlov said that as an NKVD agent he had read Mark's reports on the group. Dallin said that the only man he knew of that name was Mark Zborowski. The next meeting between the two men took place on 25th December, 1954. This time Lilia Dallin attended. Orlov told Lilia that when Lev Sedov was at the Bergere Clinic "Mark" sent a report to the NKVD that he had a tremendous urge for an orange and that it was provided by Lilia. This was a true and Lilia now came to the conclusion that Mark Zborowski was indeed a Soviet agent and told Orlov that his suspicions must be correct. Two days later Orlov told the FBI that there was a known Soviet agent in the United States. The former NKVD agent, Alexander Orlov, appeared before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in September 1955. He disclosed that Mark Zborowski had been involved in the killing of Ignaz Reiss and Lev Sedov. Zborowski appeared before the committee in February 1956. He admitted to being a Soviet agent working against the supporters of Leon Trotsky in Europe in the 1930s but denied that he had continued these activities in the United States. Lilia Dallin appeared before the committee in March 1956. She also gave information against Zborowski. However, it was not until November 1962, that he was convicted of perjury and received a four-year prison sentence. His book, Life is with People, was published in 1962. After his release he published People in Pain (1969) that dealt with different cultural attitudes towards pain and the possibility of their application in therapy. The book included an introduction by the famous anthropologist, Margaret Mead. Zborowski eventually became director of the Pain Institute at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco until his retirement in 1984. Mark Zborowski died on 30th April, 1990.NKVD Agent

Lev Sedov

Suspected Informer

Death of Lev Sedov

Death of Rudolf Klement

Alexander Orlov

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Service, Trotsky (2009)

After the Kharin affair, of course, Trotsky knew that the Moscow communist leadership would try to disrupt and infiltrate his organization abroad. He and his entourage frequently discussed this. But he never let their talk move over into serious preventive action. He did not bother himself with such precautions. Besides, he wanted a pleasant environment for work and leisure throughout the household and was keen to sustain a mood of optimism. He needed to attract fresh faces to carry out all the many tasks. He opined that even if the Kremlin pinned a young agent on him he would win him or her over to his side." Such complacency made his operations vulnerable to penetration by spies and saboteurs, and the OGPU took full advantage. His only excuse was that he had no means of knowing in advance who was reliable and who should be shunned. He had arrived abroad in circumstances different from those which had existed before 1917 when he was always mingling with a big group of Marxists. He had no one to turn to for advice and was frequently fooled by individuals who stayed with him. They included the Sobolevicius brothers Ruvin and Abraham." Another was Jacob Franck. This was a man recommended to Trotsky by Raisa Adler, wife of Alfred, for his linguistic skills." The result was that the OGPU were acquainted Trotsky's plans throughout his Turkish stay and beyond."

Lev's tiny entourage was penetrated even more damagingly. In 1933 he was approached in Paris by someone he knew as Etienne, who volunteered to work for him. This was Soviet agent Mark Zborowski. His story was that he was a committed Trotskyist from Ukraine who had travelled to France in 1933 to offer his services. He retained Lev's complete confidence despite the reservations expressed by French comrades. Etienne aimed to become indispensable to Lev, and he succeeded. Cool-headed and assiduous, he relieved Lev of many tasks in a heavy workload. Not everyone took to him. It was far from clear where he got his money from or even how he managed to subsist. Lev's secretary Lola Estrina sympathetically invented jobs for him to do and paid him each time he did one of them. A routine was established: Etienne worked alongside Lev in the mornings and Lola took his place in the afternoons." Equipped by his handlers with a camera, Etienne photographed items in the organization's files." Lev himself lived far from sumptuously. His father sent him money but expected him to economize. Jeanne Martin, Lev's partner, had a small salary which supplemented their income." Etienne's growing prominence in this situation gave rise to suspicions among French Trotskyists.

(2) Gary Kern, A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004):

Elsa Poretsky had indeed come to Paris, but only for a short time. Having accepted Sneevhet's invitation to stay with him and his third wife in Amsterdam until she could make other arrangements, Elsa stopped off with him in Paris en route from Lausanne, as he had business to attend to. The police paid a call, but not to debrief her; rather, they were following up on an anonymous tip about Eberhardt being a Nazi agent, a tip written before Ignace's assassination and clearly as preparation for it. They were not fooled and came merely to clear up the matter.

Although she told Sneevliet that she did not want visitors, he thought that she would certainly want to meet Victor Serge, the man who had been With him in Rheims on that fateful day. But both Sneevliet and Elsa were aghast when Serge showed up with a companion: Mark Zborowski, Lev Sedov's mousey and extra-polite secretary; who went by the Party name of Etienne. The two men arrived just as the police were leaving. Elsa was suspicious of Serge because he associated indiscriminately with all sorts of people, both pro- and anti-Stalinist, and everyone wondered how, after his arrest in 1933, he had managed to get out of the Soviet Union in 1936. Krivitsky at the time declared: "No one leaves the Soviet Union unless the NKVD can use him" - a principle that perhaps applied to Elsa and himself. Elsa was inclined to regard Serge as a free-spirited literary personality who did not observe the rules, but she was horrified by his faux pas in bringing Zborowski. From this incident and the discussions that followed, she realized for the first time that Sneevhet was not exactly a member of the Trotskyist camp, as her husband had assumed when he appealed to him. After a few days, she and Sneevliet moved to Amsterdam.

About a week later, at the end of September, Hans Brusse's wife, Nora, succeeded in contacting Krivitskv and leading him to her husband, waiting at a cafe Hans told Krivitsky that Shpigelglas, now his control officer, had forbidden him to make contact, but he desperately needed advice. He related that after Sneevliet and Elsa had moved to Amsterdam, Shpigelglas sent him to watch them and find a chance to steal Ignace's papers. He went and decided that theft was too risky: Sneevliet lived on the Overtoom and had dock workers posted as guards. Brusse reported back to Shpigelglas, who was not pleased and ordered him back to Holland to get the papers at any cost, promising him a Soviet medal of honor if he succeeded, and stating openly that he could do away with the widow and son. Brusse accepted the mission, but in agitation turned to Krivitsky. Such was his story. Krivitsky advised him not to object, but rather to go and sabotage the operation - the very thing that he, KriVitskv, had done in respect to Ignace. He further advised Brusse to try to get out of secret work with the NKVD and take up general political work with other Dutch Communists. According to Krivitsky's book and his "Witness Testimony," Brusse agreed.

These two accounts do not quite say that Elsa's life was in danger, but obviously it was. Leon Trotsky, writing from exile in Mexico, immediately drew this conclusion. He hoped that press notice given the case would afford her protection and asserted that her murder would serve no purpose, as "documentary evidence is now in safe hands and will eventually be published." Indeed, the "Notes of Ignace Reiss" soon appeared in the Trotskyist Bulletin in Paris, though only in excerpts. They revealed, among other things, that Stalin had tried to organize anti-Trotskyist trials in Czechoslovakia.

(3) John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, Deadly Illusions (1993)

Zborowsky had so successfully ingratiated himself into Sedov's circle by 193'7 that he was regarded as totally loyal in Trotskyist circles. The TULIP file reveals that it was from Zborowsky that Stalin, in January 1937, obtained material that was claimed to be evidence to renew his charges against Trotsky. But TULIP, who can hardly have been unaware of Sedov's real views, appears simply to have relayed to Moscow information that he believed "The Boss" wanted to hear. For example he wrote to the Centre: "On 22 January L. Sedov, during our conversation in his apartment on the subject of the second Moscow trial and the role of the different defendants, declared, "Now we shouldn't hesitate. Stalin should be murdered."

Zborowsky's unsubstantiated reports that Trotsky and Sedov were contemplating the assassination of Stalin is contrary to all their public pronouncements and the evidence contained in Trotsky's private papers that were examined by the international commission. That it appears at all in the NKVD files is significant. Even its veracity is open to question and what Zborowsky reported may have been merely an emotional outburst rather than any practical plan and it could have been pure invention to please Stalin. This report was made before Sedov died in the French clinic where he had undergone an apparently successful operation for appendicitis. The presence of Russian emigre doctors, some of whom were suspected of being in the pay of the NKVD, led to rumours that Sedov had been murdered on Stalin's instructions. Zborowsky himself fell under suspicion of being implicated because he was one of the trusted entourage. The claim that he dispatched Sedov with a poisoned orange appears fanciful in the light of a report in his NKVD file. Made shortly after Sedov's death, Zborowsky's letter advised the Centre that an autopsy should be called for, noting that until no evidence of foul play was found it would cause panic among Sedov's former assistants. He proposed that he start a whispering campaign to implicate Krivitsky who had recently defected to Paris that July and whom he referred to by his cryptonym GROLL.

If Zborowsky had indeed poisoned Sedov, it does not seem logical that he would have encouraged an autopsy - unless he was confident that no poison would be found in the body to implicate him. The circumstantial evidence that Sedov was murdered is now far less persuasive than that which shows that Zborowsky had also helped a team of Soviet agents to loot the Trotsky archives from the a Nikolayevsky Institute in November 1936.

(4) Mark Zborowski, message to NKVD headquarters (11th February, 1937)

Not since 1936 had SONNY initiated any conversation with me about terrorism. Only about two or three weeks ago, after a meeting of the group, SONNY began speaking on this subject again. On this occasion he only tried to prove that terrorism is not contrary to Marxism. "Marxism", according to SONNY's words, "denies terrorism only to the extent that the conditions of class struggle don't favour terrorism. But there are certain situations where terrorism is necessary." The next time SONNY began talking about terrorism was when I came to his apartment to work. While we were reading newspapers, SONNY said that the whole regime in the USSR was propped up by Stalin; it was enough to kill Stalin for everything to fall to pieces.

(5) Bertrand M. Patenaude, Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009)

Earlier that month, Lyova had published a special issue of the Bulletin of the Opposition devoted to the recently issued "Not Guilty" verdict of the Dewey Commission. The publication of the Bulletin came as a relief both to Lyova and to his father, who had become impatient by its delayed appearance. In his letter to Trotsky of 4 February accompanying a copy of the proofs, Lyova gave no hint of his failing health: the sharp abdominal pains, the loss of appetite, the lassitude.

On 9 February Lyova's appendicitis became acute. In part out of mistrust towards the French Trotskyists, he decided to avoid the French hospitals and instead chose to enter a small private clinic owned and run by Russian emigre doctors and staff. The clinic employed both Red and White Russians, spanning the entire spectrum of political enmity towards Trotsky, with the inevitable Stalinist police informants among them. Lyova registered at the clinic under the false identity of a French engineer, using his companion Jeanne's family name, Martin. Evidently he was unconcerned that his illness or the effects of the anaesthetic might induce him to speak in his mother tongue.

Emergency surgery took place that same evening and the patient appeared to be recuperating well, until the

night of 13-14 February, when he was seen wandering the unattended corridors, half-naked and raving in Russian. He was discovered in the morning lying on a bed in a nearby office, critically ill. His bed and his room were soiled with excrement. A second operation was performed on the evening of 15 February, but after enduring hours of agonizing pain, the patient died the following morning. Lyova was a week shy of turning thirty-two.According to the doctors, the cause of death was an intestinal blockage, but Trotsky and Natalia could only assume that their son had been poisoned by the GPU. An autopsy turned up no sign of poisoning or any other evidence of foul play, yet Lyova's relapse seemed unaccountable to his parents, who retained an image of their son as a vibrant young man. And if poison was not involved, then why had one of the doctors asked Jeanne, just before Lyova's death, if he had recently talked of suicide? Then there was the matter of the Russian clinic, a choice that must have seemed perverse, especially considering that one of the family's most trustworthy friends in Paris was an eminent physician who could have arranged for Lyova to have the best medical care.

Such were the perplexities that afflicted the grieving parents, who secluded themselves in their bedroom at the Blue House. Joe Hansen recalled hearing Natalia's "terrible cry" perhaps at the moment she was told the news. Otherwise silence reigned over the house. For several days, the staff caught only an occasional glimpse of Trotsky or Natalia, and the mere sight of them was heart-breaking. Tea was passed to them through a half-opened door, the same ritual as five years earlier when they learned of the suicide of Trotsky's daughter Zina in Berlin. Yet for Trotsky the loss of Lyova was indeed incomparable. As he explained in a press release on 18 February, "He was not only my son but my best friend."

(6) Robert Service, Trotsky (2009)

By the winter of 1937-8 Sedov's frenetic activity was exacting an intolerable toll when he had to seek treatment for stomach pains. Consulting only a few associates, including Etienne, he went to the Clinique Mirabeau on 9 February 1938; he was sufficiently worried beforehand to write his will and testament on the same day, leaving everything to Jeanne Martin." The Mirabeau was a small hospital, east of the Bois de Boulogne, owned by a Dr Girmonski and staffed by Russians. Lola Estrina's sister-in-law, a doctor, had made a tentative diagnosis of appendicitis and recommended Dr Simkov as a surgeon. Pretending to be a French engineer, Lev reverted to Russian when he entered the premises. Dr Simkov together with Dr Thalheimer, who worked for several Paris hospitals, thought he had an intestinal occlusion. They operated on him at 11 p.m. The first result seemed positive and Lev received visits by Lola and Etienne. On 13 February, however, the patient's condition worsened. Getting up in the middle of the night, he tottered naked, febrile and delirious along the corridors. Jeanne Martin, rushing to the ward, was horrified to see he had a wide purple bruise. Dr Thalheimer wondered whether Lev had tried to take his own life. The decision was taken to give him a blood transfusion. Injections were administered on 15 February. Nothing produced any improvement and the doctors were acting more by guesswork than by scientific conviction. Leva's intestines were in paralysis. He lost consciousness and entered a coma.

Despite a further blood transfusion, Lev died at eleven o'clock that morning. His associates, while having no proof, suspected medical foul play. They guarded the corpse until an autopsy could take place. Etienne mentioned that Lev's health had been poor since the Moscow show-trials and that he had been troubled by fever .Rosenthal recalled this remark soon afterwards. Was Etienne trying to deflect attention from himself?

A telegram was sent to Trotsky and Natalya. The news shattered them and they shut themselves away for days in their bedroom and spoke to no one. When they emerged Trotsky blamed Lev's death on Stalin and the Soviet security agencies. Proof was hard to come by. The authorities in Paris barely exerted themselves, despite a barrage of requests from Coyoacan, to ascertain the truth. Trotsky suspected that the French government was more eager to sustain good relations with the USSR than to do right by a dead Trotskyist. He may well have been right. France and the Soviet Union were concerting efforts at the time to foster "collective security" in Europe against German expansionism. At any rate Trotsky accused the clinic and the doctors of being instruments in the hands of Stalin's security forces. Generally he had plenty of grounds for suspecting that a murder had taken place. The NKVD had a larger network of informers and agents in Paris than in any other foreign city after the Spanish Civil War. Etienne may not have been the main procurer of death since there were several other agents who could have organized such an assassination. And Stalin had made little secret of his desire to bring the entire group around Trotsky to extinction.

There remain doubts, though, whether it would have made sense for the NKVD to order the liquidation of Leva Sedov. Alive he was a source of intimate information about his father's plans since Etienne had permission to open the mail at his own apartment. This facility was destroyed by his death; and when, many decades later, NKVD officers had the opportunity to comment on their European operations they did not boast of having liquidated Sedov." What is more, the hospital's regular doctors were not the only ones responsible for Leva's care. Having diagnosed an intestinal blockage, they brought in experts from outside when mystified by his unresponsiveness to their treatment. Recalling how Leva had wandered in delirium around the ward, some of the medical staff were to wonder whether he had administered to himself a dose of some unknown substance in a suicide attempt. His condition perplexed everybody. Gerard Rosenthal was worried enough to persuade his father, a medical consultant, to assist at Leva's bedside. This would have made it difficult for anyone deliberately to carry out a lethal act of surgery. Furthermore, Leva's friends ensured that a toxicological analysis was carried out before the cremation.

The younger Rosenthal recorded an open verdict, despite his suspicions about Etienne, but did not deny that the death could have been caused by poisoning. Jeanne Martin, who had been by Sedov's bedside and observed nothing suspicious, was satisfied by the results of the autopsy (which she herself had demanded). The death retains its mysteries to this day. What can be said with confidence, though, is that if he had survived his treatment in the Clinique Mirabeau there would have been attempts on his life in the future. His chances of growing old had always been slim.

Trotsky produced a moving booklet about Lev. There were hints of guilt feelings arising out of the way he had sometimes handled their relationship. He condemned the Stalin regime for carrying out the crime. Trotsky and Natalya wrote to Jeanne Martin seeking custody of their grandson Seva. They wanted to bring the boy across the Atlantic to Mexico. Jeanne resisted. Tormented by the loss of Lev, instinctively she hung on to Seva. Trotsky wrote a tender letter to Seva explaining that arrangements were being made for his transfer to Coyoacan, but Jeanne refused co-operation and fled Paris with Seva. Leva's shocking death brought her to mental disintegration. Her mood became unpredictable. She started using physical violence in disputes with comrades. Trotsky wrote to Etienne and Estrina saying he had totally lost confidence in her - and he called her by her married surname Molinier. Gerard Rosenthal acted as Trotsky's intermediary and lawyer in France. He pointed out to Jeanne that Seva's father might one day emerge from Siberia to reclaim his son. This forced her to face up to the fact that she had no right to continue as the boy's legal guardian. Her opposition crumbled. Alfred and Marguerite Rosmer, who had known Trotsky since before 1917 and were among his ardent French followers, took custody of Seva on the Trotskys' behalf and brought him over to Mexico in August 1939. Trotsky and Natalya became formally responsible for him.

(7) Gary Kern, A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004):

But not so strongly as to detect him. It was Zborowski who had bundled the ailing Sedov into the ambulance and told it where to go to the Clinic Mirabeau, a small establishment run by Russian emigres connected with the Union for Repatriation of Russians Abroad, the same organization to which Zborowski had belonged before infiltrating the Trotskyists, and the one where Ignace Poretsky's murderers found employment Then Zborowski contacted the NKVD, meanwhile refusing to tell the Trotskyists where Sedov had gone, ostensibly for security reasons. The death of the vigorous Sedov after a minor procedure is a medical mystery, but not a political one. Cheerful and alert immediately after the operation, he was found roaming the halls naked and delirious the same night. A second operation failed to save him from complications caused either by an injury to the abdomen or by poisoning.

Some commentators on the affair find Zborowski's complicity uncertain. Sudoplatov argues that the Center needed Sedov alive, with Zborowski next to him, in order to keep close watch of the whole Trotskyist movement, so it had no desire to kill Sedov. No doubt this was true for a time. However, the Mitrokhin archive reveals a plot to abduct Sedov shortly before his death. In February 1938, Zborowski sent reports to Moscow claiming that SYNOK - the codename for Sedov, a diminutive meaning "Little Son" or "Sonny Boy" - was advocating the assassination of Stalin - a sufficient reason for the Helmsman to insist on his speedy removal. The full context suggests that Zborowski, exaggerating loose talk of Sedov, not any real plan, forced the hand of the tyrant, who read his reports personally. He could expect that Zborowski would take over after Sedov's removal. The plan was to kidnap Trotsky's son the way General Miller had been kidnapped, but then appendicitis offered another way. Dmitry Vollkogonov, while noting Zborowski's reports, states that he found no confirmation in the NKVD archives that the Secret Service had assassinated Sedov.

Extremely sensitive matters, however, were sometimes kept out of-or purged from the files. After Sedov's death, Zborowski sent another memo to the Center proposing that demands should be raised in public for SONNY BOY's autopsy, since nothing else would allay the suspicions of the Trotskyists in Paris. This proposal seems incompatible with a conspirator in murder. In the same memo, however, he made a second proposal - that he start a whispering campaign against "GROL," suggesting that he was the assassin. Der Groll is German for "malice, hatred, resentment," and this is the codename Zborowski used for Krivitsky. Possibly the epithet originated after Krivitsky's defection, as codenames often change. Thus it would appear that Zborowski wanted to pass on the suspicion of murder to Krivitsky an act compatible with a conspirator.

Although the case cannot be proved one way or the other, the matter can be reasonably resolved if one considers that Zborowski was chiefly an informer: he fed all the information he gathered about the Trotskyists to his superiors, and they decided how to use it. It was not always in their best interest to tell him of their actions. As Sudoplatov reveals, even while casting doubt on Sedov's assassination, the NKVD ran two over-lapping networks against Trotsky's son, the first headed by Zborowski, the second by Yakov Sereuryansky. The latter used Zborowski's information to steal Trotsky's archive without Zborowski knowing exactly how it was done, though he might have had a pretty good idea.

Therefore Zborowski could send Sedov to a hospital filled with Soviet cutthroats and still not know how he died. Like Renata Steiner, he might have carried out a particular assignment, or even extemporized, without access to an overall plan. But afterwards, knowing that suspicions were rife in the emigre community, he sought to deflect unwanted attention from himself and to bring harm to a recent defector by putting out the word against RESENTMENT. Then again, he may have been in the know all along and was certain that an autopsy would prove nothing, since an untraceable poison was used.

The hardest thing to imagine is that Zborowski was not Involved in the horrible things that happened to the Trotskyists in the late 1930s. The next one was in the making. After his son's death, Trotsky initiated an investigation of Etienne, entrusting the matter to Rudolf Klement, his German translator and onetime aide in Turkey. Klement put together a file and planned to take it to Brussels on July 14, where he would circulate it among various, branches of the Opposition. But no one in Brussels ever saw him. A few days later three of the Trotskyists, including Trotsky, received a typewritten letter announcing Klement's break with the organization and denouncing Trotsky for his Nazi connections. Each of the three copies bore a different signature: Klement, Adolphe and Frederic, the last two being Party names Klement had used in the past. Oddly, his current pseudonym - Camille - was neglected; perhaps a fourth copy of the letter got lost in the mail. The Trotskyists could not conceive that Klement had been an NKVD plant all along and concluded that the letter had been written under compulsion. About a week later his headless body was discovered floating in the Seine, recognized by a scar on his hand.

After this horror, Trotsky received an anonymous letter warning him that a spy named Mark had infiltrated the Parisian group. The letter was sent by Alexander Orlov; defected in July, who knew about TULIP's work while in the service. Lilia Estrin was with Trotsky in Mexico when he read the warning in 1939, but both of them discounted it because other letters (probably sent by the NKVD) had warned Trotsky against other intimates of his circle, including Lilia. Blinded by the shotgun attack, Trotsky was undone: he realized that he could not spend all of his time investigating every member of his staff, yet failure to do so would leave him defenseless against infiltration. Even though he believed that his son had been murdered by the NKVD, he refused to act on the letter; Lilia returned to Paris and told Zborowski all about it.

(8) Bertrand M. Patenaude, Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009)

Zborowski and his family lived in a comfortable apartment building in Paris, courtesy of the GPU, and in his spare time he was able to pursue his studies in ethnology. It is hard to imagine him going to much trouble to exchange all this for an uncertain future in Mexico alongside the ultimate outlaw.

Then came the Klement murder in July 1938. About two weeks later Trotsky received a letter purporting to be from the victim, writing as a disillusioned follower. An obvious provocation, the text accused Trotsky of collaborating with the Gestapo and of behaving in a Bonapartist manner, and declared the bankruptcy of the nascent Fourth International. Somehow, Klement's death helped confirm Sneevliet in his suspicion that Zborowski was a GPU informant, a charge that he began to make openly that autumn. So did Victor Serge, like Sneevliet once a close confederate of Trotsky's who had lately become an irritant. Krivitsky and Reiss's widow, meanwhile, voiced suspicions about Serge, detecting the hand of the GPU in his release from Soviet exile two years earlier.