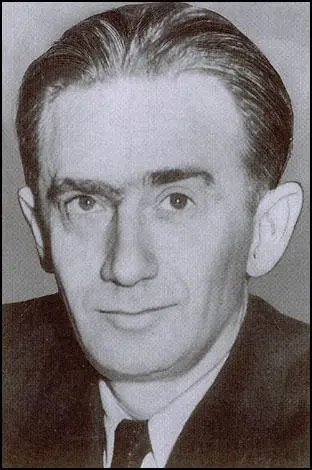

Henricus Sneevliet

Hendricus (Henk) Sneevliet was born in Rotterdam on 13th May, 1883. He was active in the trade union movement and became friends with Rosa Luxemburg. He also helped to form the Indonesian Communist Party in 1914. According to Max Shachtman: "Sneevliet was one of the few remaining personal links between the revolutionary present and the revolutionary past. If ever there was a miasmatic reformist atmosphere in which to grow up in the workers' movement, it was the atmosphere created by the opportunists who led and developed the Dutch social democracy.... His radicalism was not of the contemplative type. Raised in a land that was rotten with imperialistic prejudice, especially toward the darker-skinned inferiors of the Indies from whom it extorted fabulous riches, he was nevertheless of that rare and durable revolutionary temper which led him to work at undermining the rule of his masters precisely at the most vulnerable and most forbidden spot - the Dutch East Indies themselves."

After the Russian Revolution he became a member of the Comintern. Sneevliet impressed Lenin sent him as a Comintern representative to China, to help the formation of Communist Party of China. However, he gradually became disillusioned with the rule of Joseph Stalin and in 1927 Sneevliet formed his own party, the Revolutionair Socialistische Partij (RSP).

Left Opposition

Sneevliet was unconvinced by the Show Trial and conviction of Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and Ivan Smirnov. After their execution on 25th August, 1936, Sneevliet became a supporter of Leon Trotsky. He also moved to Paris where he associated with Victor Serge and Lev Sedov. Serge pointed out that: "I had formed a close acqquaintance with Hendricus Sneevliet. In the previous year we had spoken on the same platform at evening meetings in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, for solidarity, with the Republicans of Spain. Our audiences had been working-class and wonderfully sensible. I was aware of the high caliber of his party."

Death of Ignaz Reiss

In July 1937 Sneevliet was contacted by Ignaz Reiss, a senior figure in the NKVD, who was based in Amsterdam. Sneevliet told Serge and his fellow Trotskyists that "Ignace Reiss was warning us that we were all in peril, and asking to see us. Reiss was at present hiding in Switzerland. We arranged to meet him in Rheims on 5 September 1937. We waited for him at the station buffet, then at the post office. He did not appear. Puzzled, we wandered through the town, admiring the cathedral... drinking champagne in small cafes, and exchanging the confidences of men who have been saddened through a surfeit of bitter experiences. Both of Sneevliet's sons had committed suicide - the second out of despair because virtually nothing could be done to help the anti-Nazi refugees in Amsterdam, or prevent them from being turned back at the frontier. Several young men of his Party had just died in Spain. Of what use was their sacrifice? All this had aged him a little, so that his face wore a persistent frown amid its close lines, but he never lost heart."

Reiss never turned up for the meeting. Unknown to Sneevliet, Mikhail Shpiegelglass had been instructed to organize the assassination of Reiss. According to Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001): "On learning that Reiss had disobeyed the order to return and intended to defect, an enraged Stalin ordered that an example be made of his case so as to warn other KGB officers against taking steps in the same direction. Stalin reasoned that any betrayal by KGB officers would not only expose the entire operation, but would succeed in placing the most dangerous secrets of the KGB's spy networks in the hands of the enemy's intelligence services. Stalin ordered Yezhov to dispatch a Mobile Group to find and assassinate Reiss and his family in a manner that would be sure to send an unmistakable message to any KGB officer considering Reiss's route."

Reiss was found hiding in a village near Lausanne, Switzerland. It was claimed by Alexander Orlov that a trusted friend, Gertrude Schildback, lured Reiss to a rendezvous, where the Mobile Group killed Reiss with machine-gun fire on the evening of 4th September 1937. Schildback was arrested by the local police and at the hotel was a box of chocolates containing strychnine. It is believed these were intended for Reiss's wife and daughter. Victor Serge later recalled: As we took the train back to Paris we read in a newspaper that on the previous day the bullet-riddled body of a foreigner had been picked up on the road from Chamblandes, near Lausanne. In the man's pocket was a railway ticket for Rheims."

According to Bertrand M. Patenaude, the author of Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009), Leon Trotsky blamed Henricus Sneevliet for what happened: "When he read the news, Trotsky was incensed at Sneevliet. A GPU defector who could have drawn back the curtain on the Moscow trials had been murdered in obscurity. Worldwide publicity, Trotsky argued, would have shielded Reiss from assassination. Instead, Sneevliet had acquiesced in Reiss's plan to delay any public announcement until after his impassioned letter of resignation reached the Central Committee in Moscow. Reiss was unaware that the staff member at the Soviet embassy in Paris to whom he had entrusted the posting of his letter had betrayed him, setting off a manhunt. Trotsky saw deviousness, as well as ineptitude, in Sneevliet's handling of the Reiss affair." Trotsky even suspected that Sneevliet might be working for Joseph Stalin. However, it was another member of the group who was working for the NKVD.

Walter Krivitsky

Abram Slutsky now grew very suspicious of Walter Krivitsky and insisted that he turned over his spy-ring to Mikhail Shpiegelglass. This included his second in command, Hans Brusse. Soon afterwards, Brusse made contact with Krivitsky and told him that Shpiegelglass had ordered him to kill Elsa Poretsky and her son. Krivitsky advised him to accept the mission, but to sabotage the operation. Krivitsky also suggested that Brusse should gradually withdraw from working for the NKVD. According to Krivitsky's account in I Was Stalin's Agent (1939), Brusse agreed to this strategy.

After the assassination of Ignaz Reiss, Krivitsky discovered that Theodore Maly, who had refused to kill him, was recalled and executed. He now decided to defect to Canada. Once settled abroad he would collaborate with Paul Wohl on the literary projects they had so often discussed. In addition to writing about economic and historical subjects, he would be free to comment on developments in the Soviet Union. Wohl agreed to the proposal. He told Krivitsky that he was an exceptional man with rare intelligence and rare experience. He assured him that there was no doubt that together they could succeed.

Wohl agreed to help Krivitsky defect. To help him disappear he rented a villa for him in Hyères, a small town in France on the Mediterranean Sea. On 6th October, 1937, Wohl arranged for a car to collect Krivitsky, Antonina Porfirieva and their son and to take them to Dijon. From there they took a train to their new hideout on the Côte d'Azur. As soon as he discovered that Krivitsky had fled, Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Nikolai Yezhov what had happened. After he received the report, Yezhov sent back the command to assassinate Krivitsky and his family.

Later that month Walter Krivitsky wrote to Elsa Poretsky and told her what he had done and to express concerns that the NKVD had a spy close to Sneevliet. "Dear Elsa, I have broken with the Firm and am here with my family. After a while I will find the way to you, but right now I beg you not to tell anyone, not even your closest friends, who this letter is from... Listen well, Elsa, your life and that of your child are in danger. You must be very careful. Tell Sneevliet that in his immediate vicinity informers are at work, apparently also in Paris among the people with whom he has to deal. He should be very attentive to your and your child's welfare. We both are completely with you in your grief and embrace you." He gave the letter to Gerard Rosenthal, who took it to Sneevliet who passed it onto Poretsky.

On 7th November, 1937, Krivitsky returned to Paris where Paul Wohl arranged for him to meet Lev Sedov, the son of Leon Trotsky, and the leader of the Left Opposition in France an editor of the Bulletin of the Opposition. Sedov put him in touch with Fedor Dan, who had a good relationship with Leon Blum, the leader of the French Socialist Party and a member of the Popular Front government. Although it took several weeks, Krivitsky received French papers and if needed, a police guard.

Krivitsky also arranged a meeting with Hans Brusse who he hoped to persuade him to defect. Brusse refused declaring that he had come to the meeting "in the name of the organization". He then pulled out a copy of Krivitsky's letter to Elsa. Krivitsky was deeply shocked, but denied having written the letter. He suspected that he knew he was lying. Brusse pleaded with Krivitsky to return to his work as a Soviet spy.

On 11th November, 1937, Walter Krivitsky had a meeting with Sneevliet, Elsa Poretsky, Pierre Naville and Gerard Rosenthal. Poretsky later recalled in Our Own People (1969) that Krivitsky said to her: "I come to warn you that you and your child are in grave danger. I came in the hope that I could be of some help." She replied: "Your warning comes too late. Had you done this in time Ignaz would be alive now, here with us... If you had joined him, as you said you would and as he expected, he would be alive and you would be in a different position." Krivitsky, visibly shocked by her response, said: "Of all that has happened to me this is the hardest blow."

Krivitsky then told the group that Brusse had showed him the letter that he had sent to Poretsky. He asked Rosenthal if he had showed the letter to anyone before giving it to Sneevliet. He admitted that he had asked Victor Serge to post the letter. He later admitted to Sneevliet that he had also shown it to Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky knew that one of these people had given a copy of the letter to Brusse, who had remained loyal to the NKVD.

Death of Lev Sedov

On 9th February, 1938, Trotsky's son, Lev Sedov, complained of severe stomach pains and was taken by Mark Zborowski to the Bergere Clinic, a small establishment run by Russian émigrés connected with the Union for Repatriation of Russians Abroad in Paris. Sedov had a operation for appendicitis that evening. It was claimed that the operation was successful and was making a good recovery. However, according to Bertrand M. Patenaude: "The patient appeared to be recuperating well, until the night of 13-14 February, when he was seen wandering the unattended corridors, half-naked and raving in Russian. He was discovered in the morning lying on a bed in a nearby office, critically ill. His bed and his room were soiled with excrement. A second operation was performed on the evening of 15 February, but after enduring hours of agonizing pain, the patient died the following morning."

Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001) has argued that Alexander Orlov, a former NKVD agent, believed Sedov was murdered: "What concerned Orlov greatly was the fact that the hospital Sedov had been taken to, and where he expired, was the small clinic of Professor Bergere in Paris. Exactly a year earlier, Orlov had been in the same clinic because of his car accident while at the front. He had been cared for at the Bergere Clinic because it was a hospital that was trusted by the KGB to take care of high-ranking Soviet officials. Professor Bergere and his staff were sympathetic towards the Communist cause and under the influence of the KGB. Orlov was in Spain at the time of Sedov's death and was unable to ascertain the complete facts, but speculated that at the moment the KGB Centre had been apprised of the circumstances by Mark, the decision had been made to take advantage of the situation and eliminate Sedov. The autopsy performed by the KGB hirelings had to have been bogus to conceal the true cause of death."

Mark Zborowski

Leon Trotsky was devastated by the death of his eldest son. In a press release on 18th February he stated: "He was not only my son but my best friend." Trotsky received information from several sources that Mark Zborowski was an NKVD agent. He asked Rudolf Klement to carry out an investigation of Zborowski. According to Gary Kern: "Klement put together a file and planned to take it to Brussels on July 14, where he would circulate it among various branches of the Opposition. But no one in Brussels ever saw him."

Trotsky and several other members of the Left Opposition received a typewritten letter announcing that Klement had broken with the organization because of "Trotsky's Nazi connections". The Trotskyists concluded that the letters had been written under compulsion and that he was a captive of the NKVD. About a week later his headless body was discovered floating in the Seine. As a result of peculiar scars and marks on the body, it was identified as that of Klement.

Second World War

Hendricus Sneevliet returned to Rotterdam and after the invasion of the Netherlands on 10th May, 1940, he led the resistance to the German occupation. He was arrested by the Gestapo and executed on 12th April, 1942. Later that month it was announced: "Henricus Sneevliet, founder and chairman of an illegal political party in Holland, and seven collaborators have been sentenced to death and executed at The Hague on a charge of sabotage."

Primary Sources

(1) Max Shachtman, Life and Death of Henricus Sneevliet (1942)

In the middle of April this year, the press in Europe announced that “Henricus Sneevliet, founder and chairman of an illegal political party in Holland, and seven collaborators have been sentenced to death and executed at The Hague on a charge of sabotage.”

The report definitely and tragically confirmed what had been rumored for some time since the Nazi occupation of Holland - that Henk Sneevliet and his comrades had remained at their posts of battle even after the German steamroller flattened out Holland, that he was intent upon continuing the work of organizing the working class to which his whole conscious life had been devoted.

Sneevliet was one of the few remaining personal links between the revolutionary present and the revolutionary past. If ever there was a miasmatic reformist atmosphere in which to grow up in the workers’ movement, it was the atmosphere created by the opportunists who led and developed the Dutch social democracy. No wonder - whole strata of the Dutch working class were corrupted and bribed by their lords, who ruled an empire in the Far East of such lush richness that at this very moment they are willing to lay down every life at their disposal - their own excepted - for its reconquest. Sneevliet was, therefore, either very fortunate, or forged of different metal, or both, for he eschewed reformism long before the First World War and became, from the beginning of his activity in the Dutch labor movement, a comrade-in-arms of that valiant and militant band of revolutionists who rallied around the left-wing organ Tribune - Anton Pannekoek, David Wijnkoop, Henriette Roland-Holst and others. Comrade of theirs, he was also a comrade and friend of the best Marxists in Europe of the time, of the imperishable Rosa Luxemburg in the first place.

His radicalism was not of the contemplative type. Raised in a land that was rotten with imperialistic prejudice, especially toward the darker-skinned “inferiors” of the Indies from whom it extorted fabulous riches, he was nevertheless of that rare and durable revolutionary temper which led him to work at undermining the rule of his masters precisely at the most vulnerable and most forbidden spot - the Dutch East Indies themselves. How many men, even revolutionary men, of the world-ruling white race do we know who have gone deliberately to the dark villages and plantations of the colonial peoples for the purpose of mobilizing them against their “superiors”? Of the very, very few, Sneevliet was one, and one of the best.

The white revolutionist - not a true Dutch Jonkheer, but at the very least still a “Mijnheer” - proceeded to the Dutch East Indies, to the burning islands of Sumatra and Java to organize the first important revolutionary socialist movement among the native slaves of his own country’s overlords. The work, perilous, dramatic, painfully difficult, politically invaluable, spiritually satisfying (how I wish Sneevliet had committed to paper some of the stories of his work in the Indies which he once told me throughout a night and into the dawn, stories that rivalled anything in the literature of romance), exercised a powerful attraction upon him and he continued it for years after the Dutch colonial administration banished him from the Indies and forbade his ever returning to them. The Jonkheers were outraged at this blatant treachery by “one of their own” who stimulated and organized and taught the early class-conscious movement of the East Indian natives against the foreign invader and exploiter.

Toward the end of the war, or right afterward (I do not remember exactly at the moment), Sneevliet found himself in China, where he established contact with the revolutionary nationalist movement of the Chinese bourgeoisie, with the Sun Yat-Sen who was to become the idol of the Kuomintang, and with Chen Tu-hsiu, leader of China’s intellectual renaissance who was to become a founder and then the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. He was with the first Bolshevik emissaries to China and helped establish relations between that country and the young Soviet republic; he was with the first congress of Chinese Bolsheviks to launch the Communist Party.

We find him in Moscow in 1920, a delegate to the Second World Congress of the Communist International from the Communist Party of the East Indies, appearing under the pseudonym he then bore, “Ch. Maring.”

Together with Lenin, M. N. Roy and others, he functioned in the famous commission which drew up the fundamental theses of the International on the colonial and national questions; he was the commission’s secretary and there is no doubt that much that is contained in those theses was based on the rich experiences he had accumulated in his work in the East, perhaps the only one in the entire commission who had such experiences, for even Roy at that time was little more than a communistically-varnished Indian nationalist without much experience beyond the German-subsidized propaganda for Indian independence he had carried on during the war from a Mexican retreat.

The policy of concentrating upon work in the reformist trade unions encountered stiff resistance in Holland from Sneevliet and his friends. They had under their leadership the NAS (National Labor Secretariat), a left-wing, semi-syndicalist trade union movement which existed, on a small scale, alongside the big unions controlled by the Stalinists. It is not hard to imagine the overbearing, bureaucratic tactics employed by Zinoviev, Lozovsky & Co. to “convince” the Dutch comrades of the proper tactics to employ. Others might have been more successful, above all in other circumstances. But the real circumstances were the noticeable beginnings of the degeneration of the International. Sneevliet rebelled against it. He broke with the Comintern and became an increasingly aggressive critic of Stalinism.

With his comrades, he formed the small but entirely proletarian and militant Revolutionary Socialist Party of Holland. As the struggle in the Communist International between Stalinism and Trotskyism came to a head, Sneevliet and his comrades moved closer to the latter. In 1923-33, and especially after the miserable collapse of Stalinism before Hitler, a union was consummated between Sneevliet and the RSP and the International Left Opposition. Together they proclaimed the need of organizing and launching the Fourth International. In this declaration the signature of Sneevliet and his party was of considerable importance and weight.

(2) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

September 1937....I had formed a close acqquaintance with Hendricus Sneevliet. In the previous year we had spoken on the same platform at evening meetings in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, for solidarity, with the Republicans of Spain. Our audiences had been working-class and wonderfully sensible. I was aware of the high caliber of his party. He now informed me that a leading official in the GPU's Secret Service, resident in Holland, had been heartbroken by the Zinoviev trial and crossed over to the Opposition: Ignace Reiss was warning us that we were all in peril, and asking to see us.

Reiss was at present hiding in Switzerland. We arranged to meet him in Rheims on 5 September 1937. We waited for him at the station buffet, then at the post office. He did not appear. Puzzled, we wandered through the town, admiring the cathedral, which was still shattered from the bombardment, drinking champagne in small cafes, and exchanging the confidences of men who have been saddened through a surfeit of bitter experiences. Both of Sneevliet's sons had committed suicide - the second out of despair because virtually nothing could be done to help the anti-Nazi refugees in Amsterdam, or prevent them from being turned back at the frontier. Several young men of his Party had just died in Spain. Of what use was their sacrifice? Long ago, Sneevliet had been deported to the Dutch East Indies, where he had founded a popular party; the friends of his youth had been sentenced to penal servitude for life and the pleas he had since made on their behalf came to nothing. In his own country, the forces of Fascism were openly growing, although the bulk of the population was opposed to them. Sneevliet sensed the approach of the war in which Holland, its working class, and its developed culture would be inevitably smashed: doubtless only at the beginning, only to rise again later - but when, how? "Is it necessary for us to pass through blood-baths and utter darkness? What can one do?"

All this had aged him a little, so that his face wore a persistent frown amid its close lines, but he never lost heart. "It is strange," he remarked, "that Reiss hasn't come. He is such a punctual man..." As we took the train back to Paris we read in a newspaper that on the previous day the bullet-riddled body of a foreigner had been picked up on the road from Chamblandes, near Lausanne. In the man's pocket was a railway ticket for Rheims.

Three days later Elsa Reiss, the widow, told us in a broken voice of the trap that had been laid. A woman comrade named Gertrude Schildbach had arrived. She, like them, had wept in anguish at the news of the Moscow executions. She had known Reiss for fifteen years, and came now to ask his advice. They went out together; the comrade left chocolates for the wife and child. These were filled with poison. In the convulsed fingers of the murdered man a handful of gray hair was found... The Communist-influenced press in Switzerland wrote that a Gestapo agent had just been liquidated by his colleagues. Not a single newspaper in Paris would take our disclosures, detailed as they were.

I paid a visit to Gaston Bergery at the office of La Fleche. Bergery was running a left-wing movement called Le Frontisme, which was directed simultaneously against the monopolies and against Communism. He was an elegant, pugnacious character with open but subtle features, and with talents equally appropriate, it seemed, either for mass agitation or a Government position. He was also fond of rich living and quite evidently ambitious; we all knew that he could quite easily turn one day either to the Fascist Right or towards revolution. Within the Popular Front he maintained a position of independence. "We will publish!" he told me. The silence was broken. Our investigation laid the crime open to the light of day. Senior Russian officials, protected by diplomatic immunity, were asked to pack and be out within three days. The inquiry revealed that minute preparations for a kidnapping were being hatched around the person of Leon Sedov, Trotsky's son. An employee of the USSR trade mission, Lydia Grozovskaya, was indicted, freed on very substantial bail, closely followed, yet managed to disappear. Several times, the investigation seemed to falter. We informed the Minister of the Interior, Marx Dormoy, an old right-wing Socialist, hard and conscientious, who promised that the case would not be hushed up and kept his word.

A certain somebody, who was sure that he was about to be killed, telephoned, demanding to see us. Leon Sedov, Sneevliet, and myself met this person in the office of a Paris lawyer, Gerard Rosenthal. He was a little thin man with premature wrinkles and nervous cves Walter Krivitsky, whom I had met several times in Russia. Together with Reiss and Brunn he had headed the Secret Service and was engaged in amassing arms for Spain. Against his wishes he had taken part in preparing the ambush for his friend; he was then ordered to "liquidate" Reiss's widow before returning to Moscow.

Conversation was painful at first. He told Sneevliet, "We have a spy in your party, but I do not know his name," and Sneevliet, honest old man that he was, burst out in anger: "You scoundrel!" He told me that our mutual friend Brunn had just been shot in Russia, like most of those who had been secret agents in the first period of the Revolution. He added that, despite all, he felt very distant from us and would remain loyal to the revolutionary State; the historic mission of this State was far more important than its crimes, and besides he himself did not believe that any opposition could succeed. One evening I had a long talk with him on a dark, deserted boulevard next to the sinister wall of the Sante prison. Krivitsky was afraid of lighted streets. Each time that he put his hand into his overcoat pocket to reach for a cigarette, I followed his movements very attentively and put my own hand in my pocket.

"I am risking assassination at any moment," he said with a feeble, piqued smile, "and you still don't trust me, do you?"

"That's right."

"And we would both agree to die for the same cause: isn't that so?" "Perhaps," I said. "All the same it would be as well to define just what this cause is."

In February 1938 Leon Sedov, Trotsky's eldest son, died suddenly in obscure circumstances. Young, energetic, of a temperament at once gentle and resolute, he had lived a hellish life. From his father he inherited an eager intelligence, an absolute faith in revolution, and the utilitarian, intolerant political mentality of the Bolshevik generation that was now disappearing. More than once we had lingered until dawn in the streets of Montparnasse, laboring together to comb out the mad tangle of the Moscow Trials, pausing from time to time under a street lamp for one or the other of us to exclaim aloud: "We are in a labyrinth of utter madness!" Overworked, penniless, anxious for his father, he passed his whole life in that labyrinth. In November 1936 a section of Trotsky's archives, which had been deposited in secret a few days previously at the Institute of Social History, 7 Rue Michelet, were stolen in the night by criminals who simply cut through a door with the aid of an acetylene torch. I helped Sedov in his pointless investigation; what could be more transparent than a burglary like this?

Later on he apologized for refusing to give me his address when he went away to the Mediterranean coast for a rest: "I am giving it only to our contact man - I really have to be wary of the least indiscretion..." And we discovered that down at Antibes two of Reiss's murderers had lived near to him; another was in lodgings actually next door to his own. He was surrounded at every turn, and suffered fevers of anxiety each night. He underwent an operation for appendicitis in a clinic run by certain dubious Russians, to which he had been taken under an assumed identity. There he died, perhaps as a result of culpable negligence; the inquest revealed no definite findings ... We carried his coffin of white wood, draped with the red Soviet flag, to the Pere Lachaise cemetery. He was the third of Trotsky's children that I had seen die, and his brother had just disappeared into Eastern Siberia.

At the cemetery, a tall, thin, pale young man came to shake my hand. His face was downcast, his gray eyes piercing and wary, his clothes shabby. I had known this young doctrinaire in Brussels and we did not get on together: Rudolf Klement, secretary of the Fourth International. In his efforts to infuse some life into this feeble organization he worked at a fanatical pitch, committing in due course gross political blunders that I had many a time rebuked. On 13 July of the same year (1938), I received an express message: "Rudolf kidnapped in Paris ... In his room everything was in order, the meal ready on the table..." Forged letters from him - or genuine ones dictated at pistol-point - arrived from the Spanish border. Then, a headless body resembling Klement was fished out of the Seine at Meulan. The Popular Front press said nothing, of course. Friends of the missing man identified the decapitated corpse by the characteristic shape of the torso and hands. The Communist daily papers L'Humanite and Ce Soir joined the argument, and a Spanish officer, actually a Russian who was afterwards nowhere to be found, declared that he had seen Klement at Perpignan on the day of his disappearance. The trail having now been confused, the case was closed.

(3) Bertrand M. Patenaude, Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009)

Zborowski regularly supplied Moscow with articles from the Bulletin of the Opposition before they appeared in print, and with copies of Trotsky's letters and manuscripts, including portions of his book-length indictment of Stalin, The Revolution Betrayed, which turned up on Stalin's desk before its publication in Paris in the summer of 1937. That August came Zborowski's triumph, when Lyova (Lev Sedov) went to the south of France and entrusted him with a small notebook containing the addresses of Trotskyists living outside the Soviet Union."As you know, we have dreamed about getting hold of it for a whole year," an exultant Zborowski wrote to his superiors using his codename, Tulip, "but we never managed it before, because SONNY would never let it out of his hands. I enclose herewith a photo of these addresses".

During Lyova's absence from Paris, Zborowski stood in for him in negotiations to arrange a meeting with Ignace Reiss, the first of the GPU defectors. In making his break with the Kremlin, Reiss, the illegal resident in Belgium, had turned for help to the Dutchman Henk Sneevliet, a Communist member of parliament and trade union leader who had once been a close comrade of Trotsky's. Sneevliet, working through Zborowski, invited Lyova to meet Reiss on 6 September 1937 in Reims - which is where the defector might have met his end had a GPU mobile squad not machine-gunned him to death a day earlier on a rural road outside Lausanne.

When he read the news, Trotsky was incensed at Sneevliet. A GPU defector who could have drawn back the curtain on the Moscow trials had been murdered in obscurity. Worldwide publicity, Trotsky argued, would have shielded Reiss from assassination. Instead, Sneevliet had acquiesced in Reiss's plan to delay any public announcement until after his impassioned letter of resignation reached the Central Committee in Moscow. Reiss was unaware that the staff member at the Soviet embassy in Paris to whom he had entrusted the posting of his letter had betrayed him, setting off a manhunt.

Trotsky saw deviousness, as well as ineptitude, in Sneevliet's handling of the Reiss affair. Sneevliet had not only failed to inform Trotsky in a timely way about the defection; he even appeared reluctant to bring Lyova into direct contact with Reiss. Yet while Sneevliet does give the impression of being the controlling sort, he also had the feeling that Lyova's comrades in Paris could not be trusted. And in the wake of Reiss's murder, Sneevliet's misgivings came to focus on Zborowski.

In October came another defection, that of Walter Krivitsky, the chief of Soviet military intelligence in Europe. Krivitsky, who was stationed in the Netherlands, was a childhood friend of Reiss's. The two men had discussed their disillusionment with Moscow after the execution of the defendants in the first show trial in August 1936. They returned to the subject in the spring of 1937, as the terror began to ravage the ranks of the secret police and the military. Krivitsky resisted Reiss's suggestion that they simultaneously break with Moscow, arguing that in spite of everything, the USSR still represented the best hope of the international proletariat.

Reiss's murder helped Krivitsky overcome his doubts; in fact, his friendship with the dead defector left him little choice. He applied to the French government for political asylum, which brought with it police protection. Reiss's widow, meanwhile, suspected that Krivitsky had had a hand in her husband's death - or at least had failed to warn him of the danger. For his part Krivitsky, in attempting to establish contact with her through the French Trotskyists, became convinced that they had been infiltrated by the GPU. During a tense meeting at the office of Trotsky's Paris lawyer, Gerard Rosenthal, with Lyova, Sneevliet, and Reiss's widow in attendance, Krivitsky warned, "There is a dangerous agent in your party."

Krivitsky was wary of the Trotskyists for other reasons, as Lyova learned during a series of strenuous meetings with the reluctant defector in the final weeks of 1937. Trotsky and Lyova wanted Krivitsky to make a full and public break with the Kremlin, but he was torn about what to do next and eager to justify his past. Lyova lent him a sympathetic ear, thereby drawing the ire of Trotsky, who was impatient to seize the moment. After Lyova pressed Krivitsky to endorse the Fourth International, Krivitsky broke off their relationship. Although Krivitsky had come to like and respect Lyova, he found little to admire about his milieu. Trotsky, the man, was a formidable figure, politically the equivalent of a government, he said later, whereas his followers were mere children.

he rupture may have saved Krivitsky's life. That autumn, Lyova assigned Zborowski to be the defector's contact and escort. The two men ended up taking walks together, probably conversing in their native Polish, and Tulip undoubtedly supplied his GPU handlers with information about the traitor's movements. On one occasion they wandered into Pere Lachaise cemetery, where Krivitsky noticed some dubious-looking characters off in the distance and for a moment was convinced that the shooting was about to begin. Why their fraternization did not precipitate Krivitsky's murder is a mystery, perhaps best explained by Zborowski's instinct for self-preservation.

Lyova's death in February 1938 may have been a victory for the GPU, but for Zborowski it meant the loss of his chief defender. He used his position as Sonny's successor to deflect suspicion away from himself. The principal target of his intrigues was Sneevliet, who, Etienne now dutifully reported to Trotsky, had been spreading the story that Reiss's murder had resulted from Lyova's negligence. Predictably, Trotsky became outraged at the "slanderer" Sneevliet for besmirching his dead son's reputation.