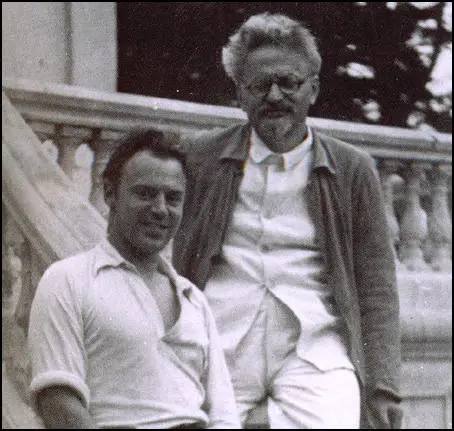

Lev Sedov

Lyova (Lev) Sedov, the son of Leon Trotsky and his second wife, Natalia Sedova, was born in St Finland in 1906. His father was in prison at the time of his birth was in Siberia for his role in the 1905 Russian Revolution.

Trotsky escaped later that year and the family moved to Austria. Another son, Sergei Sedov, was born on 21st March, 1908. Both boys were educated in Vienna: "The children spoke Russian and German. In the kindergarten and school they spoke German, and for this reason they continued to talk German when they were playing at home. But if their father or I started talking to them, it was enough to make them change instantly to Russian. If we addressed them in German, they were embarrassed, and answered us in Russian. In later years they also acquired the Viennese dialect and spoke it excellently."

On the outbreak of the First World War the family was forced to leave Vienna. They went to Zurich where Leon Trotsky published a pamphlet attacking German socialists for supported the war. In November, 1914, Trotsky moved to Paris where he became one of the editors of Social Democratic Party newspaper, Nashe Slovo. Trotsky continued to denounce the war and joined with the pacifists in urged workers not to participate in the conflict. This led to him being arrested by the French authorities and in September, 1916, he was deported to Spain. Hounded by the Spanish police, Trotsky and his wife decided to move to the United States. They arrived in New York in January, 1917 and worked with Nikolai Bukharin and Alexandra Kollontai in publishing the revolutionary newspaper Novy Mir.

Russian Revolution

On 26th February, 1917, Tsar Nicholas II ordered the Duma to close down. Members refused and they continued to meet and discuss what they should do. Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma, sent a telegram to the Tsar suggesting that he appoint a new government led by someone who had the confidence of the people. When the Tsar did not reply, the Duma nominated a Provisional Government headed by Prince George Lvov. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 28th February suggested that the Tsar should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and on the 1st March, 1917, the Tsar abdicated leaving the Provisional Government in control of the country.

Trotsky and his family arrived back in Russia in May, 1917. He disapproved of the support that many leading Mensheviks were now giving to the Provisional Government and the war effort. Trotsky gave Lenin his full support: "I told Lenin that nothing separated me from his April Theses and from the whole course that the party had taken since his arrival." The two agreed, however, that Trotsky would not join the Bolshevik Party at once, but would wait until he could bring as many of the Mezhrayontsky group into the Bolshevik ranks. This included David Riazanov, Anatoli Lunacharsky, Moisei Uritsky, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko and Alexandra Kollontai. Trotsky officially joined the Bolsheviks in July. The new prime minister, Alexander Kerensky, now realized that Trotsky was a major threat to his government and had him arrested. However, he was later released.

Leon Trotsky was the main figure to argue for an insurrection whereas Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Victor Nogin led the resistance to the idea. They argued that an early action was likely to result in the Bolsheviks being destroyed as a political force. As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) has explained why Zinoviev felt strongly about the need to wait: "The experience of the summer (the July Days) had brought him to the conclusion that any attempt at an uprising would end as disastrously as the Paris Commune of 1871; revolution was was inevitable, he wrote at the time of the Kornilov crisis, but the party's task for the time being was to restrain the masses from rising to the provocations of the bourgeoisie."

Natalia Sedova later recalled: "During the last days of the preparation for October, we were staying in Taurid Street. Lev Davydovich lived for whole days at the Smolny. I was still working at the union of wood-workers, where the Bolsheviks were in charge, and the atmosphere was tense... The question of the uprising was discussed everywhere - in the streets, at meal-time, at casual meetings on the stairs of the Smolny. We ate little, slept little, and worked almost twenty-four hours a day. Most of the time we were separated from our boys, and during the October days I worried about them. Lev and Sergei were the only Bolsheviks in their school except for a third, a sympathizer, as they called him. Against them these three had a compact group of off-shoots of the ruling democracy - Kadets and Socialist-Revolutionists. And, as usually happens in such cases, criticism was supplemented by practical arguments. On more than one occasion the head master had to extricate my sons from under the piled-up democrats who were pummeling them. The boys, after all, were only following the example of their fathers. The head master was a Kadet, and consequently always punished my sons."

Life in Russia

After the Russian Revolution both Lev Sedov's parents served in the new Bolshevik government. Lenin appointed Trotsky as the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs. Natalia Sedova was also given a post in the government. Trotsky explained in My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930): "My wife joined the commissariat of education and was placed in charge of museums and ancient monuments. It was her duty to fight for the monuments of the past against the conditions of civil war. It was a difficult matter. Neither the White nor the Red troops were much inclined to look out for historical estates, provincial Kremlins, or ancient churches. This led to many arguments between the war commissariat and the department of museums. The guardians of the palaces and churches accused the troops of lack of respect for culture; the military commissaries accused the guardians of preferring dead objects to living people. Formally, it looked as if I were engaged in an endless departmental quarrel with my wife. Many jokes were made about us on this score."

Victor Serge, a close friend of the Trotsky family later recalled: "As a child he had shared his father’s internment in Canada, and experienced the first rejoicings at the Russian Revolution, that magnificent time of newly unfurled red flags, when everything seemed to be simple and within grasp; his father’s fame, his father’s victories, the dangers to his father, his travels, his portraits in all the public buildings, his speeches which galvanized the crowds; the agony of the Civil War ... There was no place amid all this for childhood, he needed a grown man’s courage – and what could be more simple? As an adolescent he had lived through the difficult years of the struggle against the bureaucracy – plots, suicides, theses, discussions, oppositions, Lenin’s death."

Bertrand M. Patenaude, the author of Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009), has pointed out: "Lyova (Lev) was only eleven years old at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. He idolized his father, who once allowed the boy to accompany him to the front on his armoured train. Lying about his age, Lyova joined the Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, before reaching the minimum age, and later moved out of his parents' Kremlin apartment in order to live in a proletarian student hostel."

In January 1925, Joseph Stalin was able to arrange for Leon Trotsky to be removed from the government. One of his supporters, Evgenia Bosh, was devastated by the news that Trotsky had been removed from the leadership of the Red Army. Aware that Stalin was now in complete control of the Soviet Union, she decided to kill herself. Her friend, Evgeni Preobrazhensky wrote: "In her character she was made of that steel that is broken but not bent, but all these virtues were not cheap. She had to pay dearly, pay with her peace of mind, her health and her life."

Some of Trotsky's supporters pleaded with him to organize a military coup. As the former commissar of war Trotsky was in a good position to arrange this. However, Trotsky rejected the idea and instead resigned his post. Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has argued: "He left office without the slightest attempt at rallying in his defence the army he had created and led for seven years. He still regarded the party, no matter how or by whom it was led, as the legitimate spokesman of the working-class." In 1929 Trotsky was ordered to leave the Soviet Union.

The Left Opposition

In 1925 Lev Sedov married Jeanne Martin. He also joined the Left Opposition, a group that broadly supported Leon Trotsky. In 1929 he became editor of the Bulletin of the Opposition, the journal "which fought against Stalinist reaction for the continuity of Marxism in the Communist International". According to Trotsky his son also helped him write his books, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930) and History of the Russian Revolution (1932).

Lilia Estrin became Sedov's secretary. She wrote to his mother, Natalia Sedova: "I work like an ox, from early morning to late into the night, and I am content. My job (with the Institute) is interesting. After it, I work for the Bulletin and other (Trotskyite) matters which keep me up until one o'clock at night. At seven in the morning I am up again... I need no Sundays, no respite. I am a dynamic person, I need action." Sedova herself wrote: "Our son Lyova (Lev)... despair knew no bounds. He applied himself to the task which his father could not fulfill. In addition to his revolutionary activity and his literary work, our son occupied himself with higher mathematics which greatly interested him. In Paris he managed to pass examinations and dreamed of some time devoting himself to systematic work... He was accepted as a collaborator by the Scientific Institute of Holland and was to begin work on the subject of the Russian Opposition He was the only one among the youth who had had an enormous experience in this field and who was exhaustively acquainted with the entire history of the Opposition from its very inception."

Sedov became the leader of the group based in France that supported Leon Trotsky and produced the Bulletin of the Opposition. Another Russian exile, Lilia Estrin, became his secretary. One day Victor Serge brought Mark Zborowski with him to a meeting with Elsa Poretsky and Henricus Sneevliet. Elsa, whose husband had worked for the NKVD, was immediately suspicious of his story that he had been able to escape from the Soviet Union. Another agent, Walter Krivitsky, had told her: "No one leaves the Soviet Union unless the NKVD can use him".

Zbrowski began working for Sedov. According to Robert Service, the author of Trotsky (2009), some of the group were highly suspicious of Zborowski: "His story was that he was a committed Trotskyist from Ukraine who had travelled to France in 1933 to offer his services. He retained Lev's complete confidence despite the reservations expressed by French comrades. Etienne aimed to become indispensable to Lev, and he succeeded. Cool-headed and assiduous, he relieved Lev of many tasks in a heavy workload. Not everyone took to him. It was far from clear where he got his money from or even how he managed to subsist. Lev's secretary Lilia Estrin sympathetically invented jobs for him to do and paid him each time he did one of them. A routine was established: Etienne worked alongside Lev in the mornings and Lilia took his place in the afternoons. Equipped by his handlers with a camera, Etienne photographed items in the organization's files.... Etienne's growing prominence in this situation gave rise to suspicions among French Trotskyists." Pierre Naville mentioned his worries to Trotsky, who retorted: "You want to deprive me of my collaborators."

The trial of Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Ivan Smirnov, and thirteen others opened on 19th August 1936. Five of the sixteen defendants (K.B. Berman-Yurin, Fritz David, Emel Lurie, N.D. Lurie and V. P. Olberg) were actually NKVD plants, whose confessional testimony was expected to solidify the state's case by exposing Zinoviev, Kamenev and the other defendants as their fellow conspirators. The presiding judge was Vasily Ulrikh, a member of the secret police. The prosecutor was Andrei Vyshinsky, who was to become well-known during the Show Trials over the next few years.

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh entered the courtroom and began reading the long and dull summation leading up to the verdict. Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "Those in attendance fully expected the customary addendum which was used in political trials that stipulated that the sentence was commuted by reason of a defendant's contribution to the Revolution. These words never came, and it was apparent that the death sentence was final when Ulrikh placed the summation on his desk and left the court-room."

The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death. This included the NKVD agents who had provided false confessions. Joseph Stalin could not afford for any witnesses to the conspiracy to remain alive. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out that Stalin did not even keep his promise to Kamenev's sons and later both men were shot.

The Red Book

Lev Sedov wrote several articles about the Show Trials in the Bulletin of the Opposition. These were eventually published in the book, The Red Book (1936). Leon Trotsky commented: "At that time my wife and I were captives in Norway, bound hand and foot, targets of the most monstrous slander. There are certain forms of paralysis in which people see, hear, and understand everything but are unable to move a finger to ward off mortal danger. It was to such political paralysis that the Norwegian Socialist government subjected us. What a priceless gift to us, under these conditions, was Leon's book, the first crushing reply to the Kremlin falsifiers. The first few pages, I recall, seemed to me pale. That was because they only restated a political appraisal, which had already been made, of the general condition of the USSR. But from the moment the author undertook an independent analysis of the trial, I became completely engrossed. Each succeeding chapter seemed to me better than the last."

The book begins with an analysis of Stalinism. "The old petit-bourgeois family is being reestablished and idealized in the most middle-class way; despite the general protestations, abortions are prohibited, which, given the difficult material conditions and the primitive state of culture and hygiene, means the enslavement of women, that is, the return to pre-October times. The decree of the October revolution concerning new schools has been annulled. School has been reformed on the model of tsarist Russia: uniforms have been reintroduced for the students, not only to shackle their independence, but also to facilitate their surveillance outside of school. Students are evaluated according to their marks for behavior, and these favor the docile, servile student, not the lively and independent schoolboy.... A whole institute of inspectors has been created to look after the behavior and morality of the youth."

Sedov went onto argue that Joseph Stalin was sending a message to the world that he had abandoned the Marxist concept of Permanent Revolution: "Stalin not only bloodily breaks with Bolshevism, with all its traditions and its past, he is also trying to drag Bolshevism and the October revolution through the mud. And he is doing it in the interests of world and domestic reaction.... The corpses of the old Bolsheviks must prove to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has in reality radically changed his politics, that the men who entered history as the leaders of revolutionary Bolshevism, the enemies of the bourgeoisie - are his enemies also.... They (the Bolsheviks) are being shot and the bourgeoisie of the world must see in this the symbol of a new period. This is the end of the revolution, says Stalin. The world bourgeoisie can and must reckon with Stalin as a serious ally, as the head of a nation-state. Such is the fundamental goal of the trials in the area of foreign policy. But this is not all, it is far from all. The German fascists who cry that the struggle against communism is their historic mission find themselves most recently in a manifestly difficult position. Stalin has abandoned long ago the course toward world revolution."

Sedov looked closely at the trial of Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev. and Ivan Smirnov. He wrote that he suspected that five of the sixteen defendants (K.B. Berman-Yurin, Fritz David, Emel Lurie, N.D. Lurie and V. P. Olberg) were NKVD plants: "The defendants are sharply divided into two groups. The basic nucleus of the first group consists of old Bolsheviks, known world-wide, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Smirnov, and others. The second group are young unknowns, among whom are also some direct agents of the GPU; they were necessary at the trial to demonstrate that Trotsky had taken part in terrorist activity, to establish a link between Zinoviev and Trotsky, and to establish a link with the Gestapo. If after having fulfilled the tasks assigned to them by the GPU they were nonetheless shot, it is because Stalin could not leave any such well-informed witnesses alive.... The very conduct of the two groups at the trial is as different as their composition. The old men sit there absolutely broken, crushed, answer in a faint voice, even cry. Zinoviev is thin, stooped, grey, his cheeks hollow. Mrachkovsky spits blood, loses consciousness, they carry him away. They all look like people who have been run into the ground and completely exhausted. But the young rogues conduct themselves in an easy and carefree manner, they are fresh-faced, almost cheerful. They feel as though they are at a party. With unconcealed pleasure they tell about their ties with the Gestapo and all their other fables."

Sedov rejected the idea that Marxists like Trotsky would resort to assassination as a revolutionary act. He points out how followers of Karl Marx in Russia rejected the policy of the People's Will and the Socialist Revolutionaries who attempted to assassinate the Tsar and his ministers: "Individual terror sets as its task the murder of isolated individuals in order to provoke a political movement and even a political revolution. In pre-revolutionary Russia, the question of individual terror had importance not only as a general principle, but also had enormous political significance, since there existed in Russia the petit-bourgeois party of the Socialist Revolutionaries, who followed the tactic of individual terror with regard to tsarist ministers and governors. The Russian Marxists, including Trotsky during his earliest years, took part in the fight against the adventuristic tactic of individual terror and its illusions, which counted not upon the movement of the masses of workers, but on the terrorists' bomb to open the road to revolution. To individual terror, Marxism counterposes the proletarian revolution. From his youth, Trotsky adhered resolutely and forever to Marxism. If one were to publish everything which Trotsky wrote, it would make dozens of thick volumes. One would not be able to find in them a single line which betrayed an equivocal attitude toward individual terror."

Sedov quotes Leon Trotsky as saying in an article in 1911: "Whether or not a terrorist attack, even if successful, provokes disturbance in the ruling circles depends on the concrete political circumstances. In any case, this disturbance can only be short-lived; the capitalist state does not rest on ministers and cannot be destroyed together with them. The classes which it serves will always find new men; the mechanism remains intact and continues its work. But the disturbance which the terrorist attack brings to the ranks of the working masses themselves is much more profound. If it suffices to arm oneself with a revolver to arrive at the goal, why then the efforts of the class struggle? If one can intimidate high-ranking people with the thunder of an explosion, why then a party?"

In the The Red Book (1936) Sedov looks at the assassination of Sergy Kirov: "If we approach the question of individual terror in the USSR, not from a theoretical, but from a purely empirical point of view, from the point of view of so-called common sense, then it suffices to draw the following conclusion: the assassinated Kirov is immediately replaced by another Kirov-Zhdanov (Stalin has as many as he needs in reserve.) Meanwhile hundreds of people are shot, thousands, and very probably tens of thousands, are deported. The vise is tightened by several turns. If Kirov's assassination helped anyone, it is certainly the Stalinist bureaucracy. Under the cover of the struggle against terrorists, it has stifled the last manifestations of critical thought in the USSR. It has placed a heavy tombstone on all the living."

NKVD Target

Walter Krivitsky was an NKVD agent who decided to leave the service of Joseph Stalin after the recall and execution of agents such as Theodore Maly and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko. He arranged to meet Sedov in the company of Fedor Dan and warned him that there was an informer within his group. Krivitsky suggested that it might be Mark Zborowski. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "Krivitsky had no desire to join the Trotskyists, but was impressed by Sedov, admiring his revolutionary fervor, hard work and austere life style."

Robert Service, the author of Trotsky (2009) has pointed out: "In November 1936 eighty kilos of Trotsky's archive was stolen from the International Institute of Social History at 7 rue de Michelet. The director of the Institute was Boris Nikolaevski. Despite being a Menshevik, he had earned Lev Sedov's trust by lending rare books to him and Trotsky. He was a devoted collector of all material that shed light on Russian revolutionary history and Lev had decided that his father's files would be safest in his care. The burglars left no sign of breakage on entry. The police were foxed.... Everyone suspected the NKVD but no one knew how the crime had been planned and undertaken."

In January 1937, the Soviet press reported that Sergei Sedov had been arrested and charged with attempting, on the instructions of his father, a mass poisoning of workers. It is believed he was executed later that year. Lev Sedov was warned of a possible assassination attempt by Alexander Orlov, another former NKVD agent. Orlov was aware of the activities of Mikhail Shpiegelglass and his clandestine unit called the Mobile Group that had murdered former agent, Ignaz Reiss. Reiss was found hiding in a village near Lausanne, Switzerland. It was claimed by Orlov that a trusted Reiss family friend, Gertrude Schildback, lured Reiss to a rendezvous, where the Mobile Group killed Reiss with machine-gun fire on the evening of 4th September 1937. Schildback was arrested by the local police and at the hotel was a box of chocolates containing strychnine. It is believed these were intended for Reiss's wife and daughter.

Victor Serge has pointed out that towards the end of 1937 Sedov suffered from ill health. "For several months Sedov had been complaining of various indispositions, in particular of a rather high temperature in the evenings. He wasn’t able to stand up to such ill-health. He had been leading a hard life, every hour taken up by resistance to the most extensive and sinister intrigues of contemporary history – those of a regime of foul terror born out of the dictatorship of the proletariat. It was obvious that his physical strength was exhausted. His spirits were good, the indestructible spirits of a young revolutionary for whom socialist activity is not an optional extra but his very reason for living, and who has committed himself in an age of defeat and demoralisation, without illusions and like a man."

Lev Sedov had severe stomach pains. On 9th February, he was taken by Mark Zborowski to the Bergere Clinic, a small establishment run by Russian émigrés connected with the Union for Repatriation of Russians Abroad in Paris. Sedov had a operation for appendicitis that evening. It was claimed that the operation was successful and was making a good recovery. However, according to Bertrand M. Patenaude, the author of Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009): "The patient appeared to be recuperating well, until the night of 13-14 February, when he was seen wandering the unattended corridors, half-naked and raving in Russian. He was discovered in the morning lying on a bed in a nearby office, critically ill. His bed and his room were soiled with excrement. A second operation was performed on the evening of 15 February, but after enduring hours of agonizing pain, the patient died the following morning."

Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001) has argued that Alexander Orlov believed he was murdered: "What concerned Orlov greatly was the fact that the hospital Sedov had been taken to, and where he expired, was the small clinic of Professor Bergere in Paris. Exactly a year earlier, Orlov had been in the same clinic because of his car accident while at the front. He had been cared for at the Bergere Clinic because it was a hospital that was trusted by the KGB to take care of high-ranking Soviet officials. Professor Bergere and his staff were sympathetic towards the Communist cause and under the influence of the KGB. Orlov was in Spain at the time of Sedov's death and was unable to ascertain the complete facts, but speculated that at the moment the KGB Centre had been apprised of the circumstances by Mark, the decision had been made to take advantage of the situation and eliminate Sedov. The autopsy performed by the KGB hirelings had to have been bogus to conceal the true cause of death."

Leon Trotsky was devastated by the death of his eldest son. In a press release on 18th February he stated: "He was not only my son but my best friend." Trotsky received information from several sources that Mark Zborowski was an NKVD agent. He asked Rudolf Klement to carry out an investigation of Zborowski. According to Gary Kern "Klement put together a file and planned to take it to Brussels on July 14, where he would circulate it among various branches of the Opposition. But no one in Brussels ever saw him." Klement's headless corpse was washed ashore in August 1938. He was identified by a friend from peculiar scars and marks on the body.

Primary Sources

(1) Bertrand M. Patenaude, Stalin's Nemesis: The Exile and Murder of Leon Trotsky (2009)

Lyova (lev) was only eleven years old at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. He idolized his father, who once allowed the boy to accompany him to the front on his armoured train. Lying about his age, Lyova joined the Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, before reaching the minimum age, and later moved out of his parents' Kremlin apartment in order to live in a proletarian student hostel. When Trotsky led the Opposition against Stalin, Lyova plunged headlong into its activities, dropping out of technical school to become his father's closest aide and bodyguard.

"Lyova has politics in his blood," Trotsky remarked approvingly. When the Opposition went down to defeat at the end of 1927, Lyova decided to leave behind his wife and son and join his parents in exile.

(2) Lev Sedov, The Red Book (1936)

In the most diverse areas, the heritage of the October revolution is being liquidated. Revolutionary internationalism gives way to the cult of the fatherland in the strictest sense. And the fatherland means, above all, the authorities. Ranks, decorations and titles have been reintroduced. The officer caste headed by the marshals has been reestablished. The old communist workers are pushed into the background; the working class is divided into different layers; the bureaucracy bases itself on the "non-party Bolshevik," the Stakhanovist, that is, the workers' aristocracy, on the foreman and, above all, on the specialist and the administrator. The old petit-bourgeois family is being reestablished and idealized in the most middle-class way; despite the general protestations, abortions are prohibited, which, given the difficult material conditions and the primitive state of culture and hygiene, means the enslavement of women, that is, the return to pre-October times. The decree of the October revolution concerning new schools has been annulled. School has been reformed on the model of tsarist Russia: uniforms have been reintroduced for the students, not only to shackle their independence, but also to facilitate their surveillance outside of school. Students are evaluated according to their marks for behavior, and these favor the docile, servile student, not the lively and independent schoolboy. The fundamental virtue of youth today is the "respect for one's elders," along with the "respect for the uniform." A whole institute of inspectors has been created to look after the behavior and morality of the youth:

The Association of Old Bolsheviks and that of the former political prisoners has been dissolved. They were too strong a reminder of the "cursed" revolutionary past.

In the economic domain there is a sharp turn to the right: reestablishment of the market, money accounting3 and piece work. After the administrative abolition of classes, the Stalinist leadership has turned to placing its bet on the well-to-do; it is according to this policy that the differentiation among the kolkhozes as well as inside the kolkhozes takes place.

(3) Lev Sedov, The Red Book (1936)

Stalin not only bloodily breaks with Bolshevism, with all its traditions and its past, he is also trying to drag Bolshevism and the October revolution through the mud. And he is doing it in the interests of world and domestic reaction. The corpses of Zinoviev and Kamenev must show to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has broken with the revolution, and must testify to his loyalty and ability to lead a nation-state. The corpses of the old Bolsheviks must prove to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has in reality radically changed his politics, that the men who entered history as the leaders of revolutionary Bolshevism, the enemies of the bourgeoisie, - are his enemies also. Trotsky, whose name is inseparably linked with that of Lenin as the leader of the October revolution, Trotsky, the founder and leader of the Red Army; Zinoviev and Kamenev, the closest disciples of Lenin, one, president of the Comintern, the other, Lenin's deputy and member of the Politburo; Smirnov, one of the oldest Bolsheviks, conqueror of Kolchak - today they are being shot and the bourgeoisie of the world must see in this the symbol of a new period. This is the end of the revolution, says Stalin. The world bourgeoisie can and must reckon with Stalin as a serious ally, as the head of a nation-state.

Such is the fundamental goal of the trials in the area of foreign policy. But this is not all, it is far from all. The German fascists who cry that the struggle against communism is their historic mission find themselves most recently in a manifestly difficult position. Stalin has abandoned long ago the course toward world revolution.

(4) Lev Sedov, The Red Book (1936)

All this uproar and all this improbable "terrorist" turmoil is raised around Kirov. Why then Kirov? Let us admit for an instant that Zinoviev and Kamenev were really terrorists. Why would they have needed to assassinate Kirov? Zinoviev and Kamenev were too intelligent not to understand that the assassination of Kirov, absolutely a third-rate figure, immediately replaced by another Kirov-Zhdanov, could not "bring them close to power." However, in the words of the verdict, they were hoping for one thing only - to obtain power by terrorist means!

Let us also note the following: Zinoviev, says Vyshinsky, hurried up Kirov's assassination and the "desire to out-do the terrorist-Trotskyists was not the least of his motives," and at another point: "Zinoviev declared that for them it was a "question of honor" to accomplish their criminal desire (Kirov's assassination) faster than the Trotskyists."

Bakaev, for his part, declared before the court: "Zinoviev said that the Trotskyists, following Trotsky's orders, had undertaken the organization of Stalin's assassination and that we (that is, the Zinovievists) must take the initiative for Stalin's assassination into our own hands."

If Zinoviev had wanted thus to cover up" his participation and that of his friends in the terrorist acts, he ought to have been very pleased that the "Trotskyists" were taking upon themselves all the risks and that by doing so, the Zinovievists, all the while keeping out of danger, would be able, afterwards, to reap the fruits of victory.

Here there is something clearly absurd: either Zinoviev wants to cover up his participation in the terrorist acts, or he gives these acts the character of a political,demonstration (it is we, the Zinovievists, and not the Trotskyists, who ... ). But not both at the same time!

There is no doubt that if one tenth of that which the defendants were accused of were true, they would have been tried and shot at least two years ago.Kirov's assassination was the act of a few desperate Komsomols from Leningrad, without any connection whatsoever with any central terrorist organization (none existed). Neither Zinoviev, nor Kamenev, nor any other of the old Bolsheviks had anything to do with Kirov's assassination.

(5) Lev Sedov, The Red Book (1936)

The defendants are sharply divided into two groups. The basic nucleus of the first group consists of old Bolsheviks, known world-wide, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Smirnov, and others. The second group are young unknowns, among whom are also some direct agents of the GPU; they were necessary at the trial to demonstrate that Trotsky had taken part in terrorist activity, to establish a link between Zinoviev and Trotsky, and to establish a link with the Gestapo. If after having fulfilled the tasks assigned to them by the GPU they were nonetheless shot, it is because Stalin could not leave any such well-informed witnesses alive.

The artificial combination of these two groups at the trial is a typical amalgam.

The very conduct of the two groups at the trial is as different as their composition. The old men sit there absolutely broken, crushed, answer in a faint voice, even cry. Zinoviev is thin, stooped, grey, his cheeks hollow. Mrachkovsky spits blood, loses consciousness, they carry him away. They all look like people who have been run into the ground and completely exhausted. But the young rogues conduct themselves in an easy and carefree manner, they are fresh-faced, almost cheerful. They feel as though they are at a party. With unconcealed pleasure they tell about their ties with the Gestapo and all their other fables.

(6) Lev Sedov, The Red Book (1936)

Individual terror sets as its task the murder of isolated individuals in order to provoke a political movement and even a political revolution. In pre-revolutionary Russia, the question of individual terror had importance not only as a general principle, but also had enormous political significance, since there existed in Russia the petit-bourgeois party of the Socialist Revolutionaries (epigones of the heroic Narodnaya Volya), who followed the tactic of individual terror with regard to tsarist ministers and governors. The Russian Marxists, including Trotsky during his earliest years, took part in the fight against the adventuristic tactic of individual terror and its illusions, which counted not upon the movement of the masses of workers, but on the terrorists' bomb to open the road to revolution. To individual terror, Marxism counterposes the proletarian revolution.

From his youth, Trotsky adhered resolutely and forever to Marxism. If one were to publish everything which Trotsky wrote, it would make dozens of thick volumes. One would not be able to find in them a single line which betrayed an equivocal attitude toward individual terror. How strange it is to have to even speak of it today!

(7) Lev Sedov, The Red Book (1936)

The Soviet bureaucracy is the greatest danger to the USSR. But it can be removed only by an active uprising of the working class. This uprising is only possible as the result of the rebirth of the workers movement in the West, which, reaching the USSR, would undermine and sweep away the Stalinist absolutism. There can be no other road for revolutionary Marxists. And it is not with the aid of some police machinations that Stalin will discredit Marxism and Marxists! For nearly a hundred years the worldwide police have been working toward this, from Bismarck and Napoleon III, but each time they have only burned their fingers. The police falsifications and machinations of Stalin hardly surpass the other examples of this same work; but he has carried them out - and in what a manner! - by "confessions" torn from the accused by the infinitely refined methods of the Inquisition.

To discredit Marxism, Stalin puts onto the stage the same Reingold, who declares that "Zinoviev based the necessity of using terrorism on this, that although terror was incompatible with Marxism, at the present time it is necessary to cast this aside." What a beautiful accumulation of words! Zinoviev, don't you see, based this on the fact, that although this is incompatible with Marxism, this has to be cast aside."

What complete idiocy!

Toward Marxism, as toward theory in general, Stalin shows fear, and at the same time, a sort of contempt. A limited empiricist, "a practical person," Stalin has always been a stranger to the theory of Marxism. For him, Marxism, more exactly the arguments "from Marxism," are first of all a cover, a smokescreen. The "practical" arguments, those of day-to-day life and, in particular, the arguments of political gangsterism, are obviously closer to him. There, he is in his element.

If we approach the question of individual terror in the USSR, not from a theoretical, but from a purely "empirical" point of view, from the point of view of so-called common sense, then it suffices to draw the following conclusion: the assassinated Kirov is immediately replaced by another Kirov-Zhdanov (Stalin has as many as he needs in reserve.) Meanwhile hundreds of people are shot, thousands, and very probably tens of thousands, are deported. The vise is tightened by several turns.

If Kirov's assassination helped anyone, it is certainly the Stalinist bureaucracy. Under the cover of the struggle against "terrorists," it has stifled the last manifestations of critical thought in the USSR. It has placed a heavy tombstone on all the living.

In fact, it is Stalin himself who pushed isolated groups of youth who are politically backwards and desperate onto the road of terrorism. By reducing liberty to the right to be a docile subject, by stifling all social life in the USSR, by giving no one the possibility of expressing his opinion in the framework of proletarian democracy, Stalin necessarily pushes isolated and desperate men onto the road of terrorism. The personification of the regime - the party does not exist, the working class does not exist, only Stalin and the local Kaganovich exist - this also cannot fail to feed terrorist tendencies. To the extent that these really exist in the USSR, Stalin - and he alone - carries the full political responsibility. It is his regime which gives birth to them and not the Left Opposition.

(8) Edward P. Gazur, Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001)

Stalin made a great error in judgement when he banished Trotsky from the Soviet Union. Trotsky was now free to collect his thoughts and offer them to the world in a manner that he could not have done as a "prisoner" in Alma-Ata. Because of Trotsky's constant attacks on Stalin's credibility in light of the purges, Stalin's stature had become greatly diminished throughout the world while that of Trotsky had been enhanced. Stalin became increasingly paranoid and took his immediate revenge on Trotsky's relatives and former colleagues still residing in the Soviet Union, who one by one disappeared from the face of the earth. By 1937, Stalin felt that he had no alternative but to silence Trotsky's denunciations and the only way this could be accomplished was to eliminate the source. Stalin ordered the KGB to plan Trotsky's assassination no matter what the cost or repercussions.

With the background in place, Orlov's narration filled in the blank spaces. As we have seen, Orlov was able to sit in on the first of the great purge trials held in Moscow in August 1936. During this period, he came into contact with many KGB officers and learned that the KGB already had in place a secret agent in the entourage of Trotsky's son Lev (Lyova) Sedov in Paris. The agent was so highly placed that his actual identity was known to Stalin. Sedov ran the Trotskyite organisation in Paris after his father left France in June 1935 and continued the worldwide work of agitation against Stalin from this base.

Orlov could only assume that the planted agent would first ingratiate himself with Trotsky's son and then with Trotsky. This piece of information was so sensitive and so highly guarded that he could not risk asking any questions. What little information he possessed had been volunteered to him by friends and he knew better than to ask for details. In the event of the plant being compromised, each KGB officer who had even the slightest knowledge of him would be scrutinised for the minutest detail that could lead to the source of the leak. Notwithstanding the inherent danger of exposing the plant to Trotsky, Orlov resolved that he would do so at the first practical opportunity. He felt reasonably confident that with the knowledge that the plant was already in place, he was now in a position to recognise other isolated pieces of information that came to his attention from various independent sources, which could result in his identifying the secret agent whose agenda was the elimination of Trotsky.

(9) Natalia Sedova, Father and Son (1940)

Our son Leon (Lev)... applied himself to the task which his father could not fulfill. In order to ease the latter's burden he came out himself with the exposure of the vile masters of the "Moscow Trials" whom he branded for what they were and who have written into the annals of history its most shameful and most revolting pages. Leon fulfilled this task brilliantly. In our jail we read his "Red Book" with great excitement. "All very true, all very true, good boy," said his father with a friend's tenderness. We wanted so much to see him and to embrace him!

In addition to his revolutionary activity and his literary work, our son occupied himself with higher mathematics which greatly interested him. In Paris he managed to pass examinations and dreamed of some time devoting himself to systematic work. On the very eve of his death he was accepted as a collaborator by the Scientific Institute of Holland and was to begin work on the subject of the Russian Opposition He was the only one among the youth who had had an enormous experience in this field and who was exhaustively acquainted with the entire history of the Opposition from its very inception.

Our economic instability used to worry him a great deal. How he yearned for economic independence! He once wrote me about his prospective earnings. The possibilities were good but he did not yet have definite assurance. "It would be a remarkable thing" (i.e., work in the Scientific Institute), he said and then added facetiously, "I would be in a position to assist my aging parents." "Why not dream?" he asked. His father and I often recalled these words of our son with love and tenderness. Mr. Spalding - assistant supervisor of the Russian Department in Stanford University-conducted some negotiations with our son in Paris concerning a prospective work, and here is what he later wrote about Leon: "The news of Sedov's death came to me as a shock. He impressed me as an extremely able and attractive personality, his future would undoubtedly have been brilliant. We are quite unclear about the circumstances of his death: some sources of our information indicate that it was due to medical negligence, or even something more terrible. Could you find it possible to write a brief note summarizing the conversation I had with Sedov last October (1937), including the tentative agreement which I had concluded with him. I could use such a note in ease it is possible to obtain certain information from Trotsky concerning the Russian civil war and war communism."

Leon entered the revolution as a child and never left it to the end of his days. The semi-conscious loyalty of his childhood toward the revolution later matured into a conscious and firmly intrenched devotion. Once in the summer of 1917, he came from school with a bloody hand into the office of the Woodworkers Trade Union (Bolshevik) where I was then working as editor and proof-reader of its organ, "Woodworkers Echo." It was the time of hot debates which took place net only in the Tauride Palace, the Smolny, or the Circus but also in the streets, the streetcars, schools and at work. Early in the morning, as a rule, a multitude of workers milled in the officer of our union, discussing current questions, i.e., the questions involving the impending seizure of power by the proletariat For the mass of workers these questions were indissolubly bound up with the personality of L.D. They discussed his speeches--and in these discussions could be felt the unity and inflexibility of will: a burning desire to march forward, summoning for a decisive struggle with unconquerable faith in victory.

(10) John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, Deadly Illusions (1993)

Zborowsky had so successfully ingratiated himself into Sedov's circle by 193'7 that he was regarded as totally loyal in Trotskyist circles. The TULIP file reveals that it was from Zborowsky that Stalin, in January 1937, obtained material that was claimed to be evidence to renew his charges against Trotsky. But TULIP, who can hardly have been unaware of Sedov's real views, appears simply to have relayed to Moscow information that he believed "The Boss" wanted to hear. For example he wrote to the Centre: "On 22 January L. Sedov, during our conversation in his apartment on the subject of the second Moscow trial and the role of the different defendants, declared, "Now we shouldn't hesitate. Stalin should be murdered."

Zborowsky's unsubstantiated reports that Trotsky and Sedov were contemplating the assassination of Stalin is contrary to all their public pronouncements and the evidence contained in Trotsky's private papers that were examined by the international commission. That it appears at all in the NKVD files is significant. Even its veracity is open to question and what Zborowsky reported may have been merely an emotional outburst rather than any practical plan and it could have been pure invention to please Stalin. This report was made before Sedov died in the French clinic where he had undergone an apparently successful operation for appendicitis. The presence of Russian emigre doctors, some of whom were suspected of being in the pay of the NKVD, led to rumours that Sedov had been murdered on Stalin's instructions. Zborowsky himself fell under suspicion of being implicated because he was one of the trusted entourage. The claim that he dispatched Sedov with a poisoned orange appears fanciful in the light of a report in his NKVD file. Made shortly after Sedov's death, Zborowsky's letter advised the Centre that an autopsy should be called for, noting that until no evidence of foul play was found it would cause panic among Sedov's former assistants. He proposed that he start a whispering campaign to implicate Krivitsky who had recently defected to Paris that July and whom he referred to by his cryptonym GROLL.

If Zborowsky had indeed poisoned Sedov, it does not seem logical that he would have encouraged an autopsy - unless he was confident that no poison would be found in the body to implicate him. The circumstantial evidence that Sedov was murdered is now far less persuasive than that which shows that Zborowsky had also helped a team of Soviet agents to loot the Trotsky archives from the a Nikolayevsky Institute in November 1936.

(11) Mark Zborowski, message to NKVD headquarters (11th February, 1937)

Not since 1936 had SONNY initiated any conversation with me about terrorism. Only about two or three weeks ago, after a meeting of the group, SONNY began speaking on this subject again. On this occasion he only tried to prove that terrorism is not contrary to Marxism. "Marxism", according to SONNY's words, "denies terrorism only to the extent that the conditions of class struggle don't favour terrorism. But there are certain situations where terrorism is necessary." The next time SONNY began talking about terrorism was when I came to his apartment to work. While we were reading newspapers, SONNY said that the whole regime in the USSR was propped up by Stalin; it was enough to kill Stalin for everything to fall to pieces.

(12) Victor Serge, La Révolution Prolétarienne (21st February 1938)

Leon Lvovich Sedov died on 16th February at eleven o’clock in the morning in a Paris hospital, as a result of two operations made necessary by a sudden attack of appendicitis. For several months Sedov had been complaining of various indispositions, in particular of a rather high temperature in the evenings. He wasn’t able to stand up to such ill-health. He had been leading a hard life, every hour taken up by resistance to the most extensive and sinister intrigues of contemporary history – those of a regime of foul terror born out of the dictatorship of the proletariat. It was obvious that his physical strength was exhausted. His spirits were good, the indestructible spirits of a young revolutionary for whom socialist activity is not an optional extra but his very reason for living, and who has committed himself in an age of defeat and demoralisation, without illusions and like a man. Such epochs alternate, in our century, with other periods, of revival and strength, which they prepare the way for – which it is the job of all of us to prepare the way for.

Leon Lvovich seemed amazingly true to himself, in the middle of a daily life where there was no shortage of emotional strain, and of misfortunes. Our meetings were always hasty, anxious, tense for fear of wasting a minute. Five minutes after I shook his hand for the first time, we were working together to identify agent provocateurs, the Sobolevicus brothers (Senine); we combed our memories, unfortunately without success, for the name of a wretched man shot long ago, an enthusiastic little French comrade, who in Paris and then in Constantinople had been the collaborator of Jacob Blumkin, and who had been shot at the same time as he was (1929), probably without ever knowing why. Only once was some sort of human contact established between us, as we were roaming, after midnight, near the Place de Breteuil, between us the shadow of Ivan Nikitich Smirnov, one of the sixteen executed after the first Moscow trial. Sedov had known him well; he spoke to me sadly about his wife, Safonova, who had testified against him at the trial, and thereby ensured his ruin, and her own. Sedov spoke favourably of her: “She was a true Communist, a person of fine character: they must have convinced her that she was saving him in order to get her to take that attitude; and she was shot herself afterwards ...” It was the same time as the Rue Michelet affair. Then Trotsky was interned in Norway. Sedov was afraid that Stalin’s political police would manage to kidnap his father in Oslo, or kill him later, on a cargo-boat ... Sedov, with the eyes of experience, could see danger looming when it was still a long way off A few months went by and Ignaz Reiss was murdered the day before the meeting that had been fixed with Leon Lvovich and some other friends ... Amid all these circumstances Sedov kept the good humour of a practical man; he was so anxious that his face was permanently wrinkled into a frown, but he could still smile easily, and he was always wondering what had to be done next so that he could do it straightaway. He was by no means a pure theoretician or a dreamer: he had the temperament of a technician who could not be bothered with rest. A humble technician of the revolution in years of reaction: he would not have sought to be praised in any other terms.

What a passion-filled life he had led! As a child he had shared his father’s internment in Canada, and experienced the first rejoicings at the Russian Revolution, that magnificent time of newly unfurled red flags, when everything seemed to be simple and within grasp; his father’s fame, his father’s victories, the dangers to his father, his travels, his portraits in all the public buildings, his speeches which galvanised the crowds; the agony of the Civil War ... There was no place amid all this for childhood, he needed a grown man’s courage – and what could be more simple? As an adolescent he had lived through the difficult years of the struggle against the bureaucracy – plots, suicides, theses, discussions, oppositions, Lenin’s death ... The young man stood alongside his father in 1927, when defeat was inevitable, with exile or execution into the bargain. He was there when they broke down the doors of a modest home in Moscow, in order to seize the Organiser of Victory and deport him to Central Asia, near the Chinese border. He was at Alma Ata when unknown assailants tried to break into the exile’s home; Sedov defended that home. Later he was at Prinkipo, where Trotsky’s house was burned down by mysterious hands. He was in Berlin when the Trotskyist group there was disrupted by the activity of provocateurs, and when his sister Zinaida took her own life ... He was torn in two in his private life; he has left a wife and child in Russia. He was a good mathematician, and skilled in military matters (which, in August 1937, made him consider going to Spain; his friends advised him strongly against it).

Stateless – yet more devoted than anyone to the workers’ homeland of Russia! He obtained visas and residence permits only with the greatest difficulty; he had escaped from Germany before Hitlr came to power, and lived in poverty in the XVth arrondissement. Such poverty, sometimes, that he explained to me that one meal a day was quite adequate, but that in the end you felt the effects of it. He was just coming to the end of a period of privation when there opened up for him, and for all of us, the hell of the Moscow trials. It must be admitted: if anything could have broken men with wills of iron, it was this flood of tangled lies, of baffling confessions, culminating in the murder in cellars of those who were once the great leaders. The highest moral values formed by the revolution had collapsed into the mud. For Moscow Sedov was one of the main targets of a nameless intrigue, which was even more inept than it was pernicious. I remember his sheer amazement at the clumsiness of fasifiers who accused him of meeting people in a town which he could easily prove he had never visited. He worked tirelessly to gather together documents and evidence to refute the lies. M. Malraux, author of Days of Contempt, refused to testify on his behalf ... The League for the Rights of Man had to be asked repeatedly before they would give him a hearing, and then they refused to take a position on the question. None the less there were courageous people willing to accept his evidence and documentation, at a meeting chaired by old Modigliani, who was familiar with totalitarian swindles ... Those who were present, in a small ball in the Mutualité, at the confrontation between this chairman and his witness, across a conference table, will never forget the occasion: they learned how much passion and intelligence can be put into the search for truth.

Leon Sedov had long lived under constant threat. Although he was well aware of this, and was prudent by nature, he took few precautions, for precautions have their price ... Stalin probably did not expect the resounding failure of the Moscow trials which satisfied nobody but the most well-tried time-servers. As the principal witness for the prosecution in the counter-trial initiated by history, of which the work done by the committees in Paris and New York is only a tiny part, Sedov had to be silenced, but skilfully, so as not to make the responsibility for the crime too obvious. If possible they wanted to set up a plausible accident. In November 1936 a section of his father’s archives, transferred by his efforts to the Institute of Social History in the Rue Michelet, were stolen during the night by GPU agents who cut through a door with an oxyhydric torch. A few days later Sedov realised he was being shadowed; the French police arrested a former Russian emigré, a member of the “Society of the Friends of the Soviet Fatherland”, who had recently returned from Moscow ... The investigation into the murder of Ignaz Reiss had revealed, through their own confessions, that Reiss’s murderers, under the direction of the top GPU officials, had for a long time been shadowing Leon Sedov, with alarming skill. In the summer of 1936 Sedov had gone to spend a few weeks by the sea in the south of France; Renata Steiner, who was arrested in Switzerland for having prepared the ground for Reiss’s killers, took lodgings in the same boarding house; every day she reported on his movements to another of those charged in the Reiss affair, Semirensky, who was living in the neighbouring house. He lived in Paris, under a false name, right next door to Leon Sedov. A little later, when Sedov had planned to travel to Mulhouse, the same executioners prepared an ambush for him in the station of that town. It was only by chance that Sedov didn’t make the journey.

Did he die a natural death? The medical evidence seems to confirm that he did. But in the atmosphere we live in, how can we dismiss terrible suspicions? Is it not possible to artificially provoke such ailments? Killers lived right alongside him. They may have missed their chance at a particular moment without letting him escape for good. If this is the case, medical tests will tell us nothing. For my part, I prefere to ignore this hypothesis: let us not add to what is akeady certain in this nightmare, which is great enough already ... Thus in one way or another the cynical warning of Radek to the “Trotskyists of France and Spain” has been fulfilled: “they are paying dearly”. Andrès Nin, disappeared – murdered – in a prison of the Spanish Republic: Kurt Landau, who was, with Trotsky and Rosmer, a member of the First International Secretariat of the Communist Left Opposition, has disappeared likewise; Erwin Wolf, who was Trotsky’s secretary in Oslo, has disappeared (and an agency report – admittedly unconfirmed – has announced that Erwin Wolf has been shot in Moscow, at the beginning of February, at the same time as Antonov-Ovseenko. Kidnapped in Barcelona, shot in Moscow?) ... Sedov, finally, dead of natural causes ... A year of horrors!

In him Trotsky may have lost his last child. His eldest daughter, Nina, died of tuberculosis in Leningrad during the period of his deportation. The Central Committee of the Party refused to give the exile permission to see her on her death-bed. His younger daughter, Zinaida, committed suicide in Berlin a few days after being stripped of her Soviet nationality, which meant she was cut off for ever from her husband and her homeland. His younger son, Sergei Sedov, a technician who was not involved in any kind of political activity, disappeared in Moscow about two and a half years ago, with his wife. We heard he was deported to Krasnoyarsk, and then agency despatches reported his arrest in this town where he was said to have “attempted to cause the mass asphyxiation of workers in the factory where he was employed”. Since then, there has been no news of him. Has he been shot? Imprisoned in a northern concentration camp? Who is even trying to find out?

In Leon Lvovich, Trotsky has lost more than a son of his own blood – he has lost a son in spirit, an irreplaceable companion in struggle. Let him at least know that this dark hour we are all with him, unreservedly. Whatever may divide us, in doctrine and in history, is in human terms of infinitely less importance than what unites us in the service of the working class against dangers which demand from each of us the greatest steadfastness. I know that I am writing here for many friends and comrades, who differ in their ideas, in their language, in their forms of action: and who are sometimes sharply divided by controversy – but who are united in something essential which gives meaning to their lives. We have all lost in Sedov a comrade of rare quality.

(13) Edward P. Gazur, Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001)

The strange death of Trotsky's son Lev Sedov on 16 February 1938 was also of concern to Orlov and perplexed him considerably. From what he knew of the son, there was no valid reason why a person barely past the age of thirty and in robust health should pass away. Sedov had a history of abdominal problems and had recently complained of stomach pains. After a severe attack, he had been taken by ambulance to a hospital and, following an emergency operation for appendicitis, had appeared to be out of danger and on his way to a normal recovery. Less than a week after the operation, the patient had had a dubious relapse manifested by hallucinations and verbal obscenities towards the staff and other patients. His condition deteriorated rapidly and he died on the 16th. A cursory autopsy revealed no unnatural causes for the death. Sedov's wife was convinced that he had been poisoned by the KGB.

What concerned Orlov greatly was the fact that the hospital Sedov had been taken to, and where he expired, was the small clinic of Professor Bergere in Paris. Exactly a year earlier, Orlov had been in the same clinic because of his car accident while at the front. He had been cared for at the Bergere Clinic because it was a hospital that was trusted by the KGB to take care of high-ranking Soviet officials. Professor Bergere and his staff were sympathetic towards the Communist cause and under the influence of the KGB. Orlov was in Spain at the time of Sedov's death and was unable to ascertain the complete facts, but speculated that at the moment the KGB Centre had been apprised of the circumstances by Mark, the decision had been made to take advantage of the situation and eliminate Sedov. The autopsy performed by the KGB hirelings had to have been bogus to conceal the true cause of death.

Within five months of Sedov's mysterious death, Orlov was to learn that yet another of Trotsky's leaders had been eliminated. Rudolf Klement was a former German Communist, who had turned against Stalin and strongly supported the Trotskyites in both words and deeds. He had become a trusted member of Trotsky's proletariat and at the time was organising the founding conference of the Fourth International, the vehicle that Trotsky expected would propel his views to the world. Klement had disappeared from his Paris residence in the middle of July 1938. Within a week of his disappearance, Trotsky had received a letter from Klement addressed to him in Mexico and bearing a New York City postmark. The letter chastised Trotsky for allegedly aligning himself with the Fascists. A copy of the same letter was also received by other Trotsky luminaries. By the end of the month, a headless body was found floating in the River Seine. Because of peculiar scars and marks on the body, it was identified as that of Klement. According to Orlov, the Klement letter to Trotsky was a KGB forgery designed to make it appear that, after the denunciation, Klement had disappeared for his own reasons.Years later, Orlov would learn that when Trotsky received Klement's denunciation letter, he had been positive that the letter was a KGB forgery and that the KGB was responsible for kidnapping and then assassinating Klement.

The KGB hadn't taken into account the possibility that Klement's corpse would emerge from its watery grave, nor that the headless body would be identified. Orlov never made a direct link between the Klement assassination and Mark, but strongly felt that Mark had to have been a key player. Now Mark was the head man in Trotsky's Paris organisation and in a position to report on all its activities to Moscow.

(10) Donald Rayfield, Stalin and his Hangmen (2004)

NKVD overseas operations had suffered in the purges. Ezhov had failed to kill Trotsky, although he had infiltrated Trotsky's inner circle in Paris and stolen parts of his archives. Ezhov's last competent agent was Sergei Shpigelglas, who specialized in liquidating defectors and enugres. Shpigelglas's final action was to murder Trotsky's son, Lev Sedov, as the latter convalesced from an appendectomy." This last murder was counter-productive: it alerted Trotsky and made him warier. Shpigelglas also left such a blatant trail of blood that he damaged Franco-Soviet and Swiss-Soviet relations.