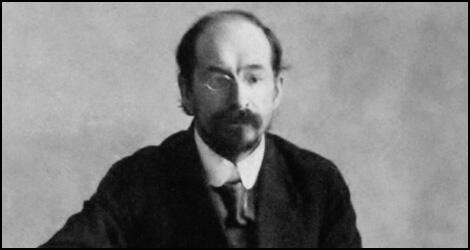

Anatoli Lunacharsky

Anatoli Lunacharsky, the son of a local government official, was born in Poltava, Ukraine, in 1875. When he was fifteen he joined an illegal Marxist study-circle in Kiev.

Lunacharsky was aware of the lack of academic freedom in Russia so he decided to study social sciences at Zurich University. while there he developed a close friendship with Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches who had also been converted to Marxism.

In 1896 Lunacharsky returned to Russia and joined the illegal Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) but was soon arrested by Okhrana. Lunacharsky was sentenced to internal exile in Siberia where he met Alexander Bogdanov, who later became his brother-in-law.

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Vladimir Lenin and Julius Martov, two of SDLP's leaders. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists.

Julius Martov based his ideas on the socialist parties that existed in other European countries such as the British Labour Party. Lenin argued that the situation was different in Russia as it was illegal to form socialist political parties under the Tsar's autocratic government. At the end of the debate Martov won the vote 28-23 . Vladimir Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks.

Lunacharsky joined the Bolsheviks and with Alexander Bogdanov co-edited a party journal in Switzerland. He also wrote an important books on Marxist philosophy, An Essay in Positive Aesthetics and Religion and Socialism. Lunacharsky also worked with Vladimir Lenin publishing Vpered and Proletarri and smuggling copies into Russia.

Lunacharsky returned to Russian during the 1905 Revolution and co-edited the journal, Zovaya Zhizn with Maxim Gorky, the first Bolsheviks newspaper to be published legally in Russia.

When Vladimir Lenin attacked Lunacharsky for having deviant Marxist views, he left and joined the Mensheviks. In August, 1914, he began co-edited the anti-war newspaper, Our World, with Julius Martov and Leon Trotsky. when the paper was banned by the authorites Lunacharsky moved to Switzerland.

After the February Revolution Lunacharsky returned to Russia and along with Leon Trotsky joined the Bolsheviks in August, 1917. An impressive orator, Lunacharsky played an important role in persuading the industrial workers of Petrograd to support the October Revolution.

In November, 1917, Vladimir Lenin appointed Lunacharsky as the government's Commissar for Education and Enlightenment. He tried to completely reform Russian education system. He also introduced a system for subsidizing the arts. Another inovation was Workers' Faculties that provided intensive and accelerated courses to train technicians and administrators from the working classes and the peasantry.

Lunacharsky was also responsible for the Soviet Government's campaign against adult illiteracy. In 1917 over 65 per cent of the adult population were illiterate but by the time Lunacharsky left office it was virtually zero.

In 1930 Lunacharsky and Maxim Litvinov represented the Soviet Union at the League of Nations in Geneva. Joseph Stalin appointed him ambassador to Spain in but he died before he could take up his post on 26th December, 1933.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1924 Anatoly Lunacharsky wrote an autobiography for The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution.

As soon as war broke out, I joined the internationalists, and with Trotsky, Manuilsky and Antonov-Ovseyenko edited the anti-militarist journal

(2) Anatoli Lunarcharsky wrote about the role of Leon Trotsky in the failed 1905 Russian Revolution his book Silhouettes.

Trotsky's popularity among the St. Petersburg proletariat was very great by the time of his arrest, and this was increased still further by his strikingly effective and heroic behaviour at the trial. I must say that Trotsky, of all the Social Democratic leaders of 1905-06, undoubtedly showed himself, in spite of his youth, the best prepared; and he was the least stamped by the narrow emigre outlook which handicapped even Lenin. He realized better than the others what a state struggle is. He came out of the revolution, too, with the greatest gains in popularity; neither Lenin nor Martov gained much. Plekhanov lost a great deal because of the semi-liberal tendencies which he revealed. But from then on Trotsky was in the front rank.

(3) Neville Chamberlain, letter to a friend (26th March, 1939)

I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears. Moreover, she is both hated and suspected by many of the smaller States, notably by Poland, Rumania and Finland.

(4) On 16th April, 1939, the Soviet Union suggested a three-power military alliance with Great Britain and France. In a speech on 4th May, Winston Churchill urged the government to accept the offer.

Ten or twelve days have already passed since the Russian offer was made. The British people, who have now, at the sacrifice of honoured, ingrained custom, accepted the principle of compulsory military service, have a right, in conjunction with the French Republic, to call upon Poland not to place obstacles in the way of a common cause. Not only must the full co-operation of Russia be accepted, but the three Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, must also be brought into association. To these three countries of warlike peoples, possessing together armies totalling perhaps twenty divisions of virile troops, a friendly Russia supplying munitions and other aid is essential.

There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge.