Prison Camps in Siberia

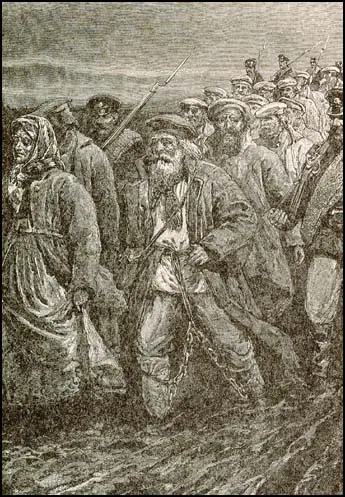

In 1754 the Russian government decided to send petty criminals and political opponents to eastern Siberia. Sentenced to hard labour (katorga), the convicts had to travel mostly on foot and the journey could take up to three years and it is estimated about half died before they reached their destination. George Kennan, the author of Siberia and the Exile System (1891) has explained: "When criminals had been thus knuted, bastinadoed, branded, or crippled by amputation, Siberian exile was resorted to as a quick and easy method of getting them out of the way; and in this attempt to rid society of criminals who were both morally and physically useless Siberian exile had its origin. The amelioration, however, of the Russian criminal code, which began in the latter part of the seventeenth century, and the progressive development of Siberia itself gradually brought about a change in the view taken of Siberian exile. Instead of regarding it, as before, as a means of getting rid of disabled criminals, the Government began to look upon it as a means of populating and developing a new and promising part of its Asiatic territory."

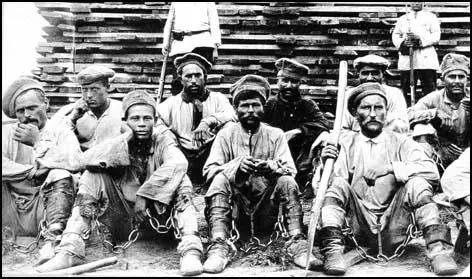

Over the next 130 years around 1.2 million prisoners were deported to Siberia. Some prisoners helped to build the Trans-Siberian Railway. Others worked in the silver and lead mines of the Nertchinsk district, the saltworks of Usolie and the gold mines of Kara. Those convicts who did not work hard enough were flogged to death. Other punishments included being chained up in an underground black hole and having a 48lb beam of wood attached to a prisoner's chains for several years. Once a sentence had been completed, convicts had their chains removed. However, they were forced to continue living and working in Siberia.

Praskovia Ivanovskia explained that the cold was a major problem: "The Kara prison most resembles a tumbledown stable. The dampness and cold are ferocious; there's no heat at all in the cells, only two stoves in the corridor. The cell doors are kept open day and night - otherwise we would freeze to death. In winter, a thick layer of ice forms on the walls of the corner cells and at night, the undersides of the straw mattresses get covered with hoarfrost. Everyone congregates in the corridor in winter, because it's closer to the stoves and you get a warm draft. Since the cells farthest from the stove are completely uninhabitable, the people who live in them carry their beds into the corridor."

On 1st March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by members of the People's Will. The following month Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman and Timofei Mikhailov were executed for their involvement in the assassination. Others such as Gesia Gelfman, Olga Liubatovich, Vera Figner, Grigory Isaev, Mikhail Frolenko and Anna Korba were exiled to Siberia.

Anna Yakimova, who was also pregnant, had her baby in the prison and had to watch over him night and day to protect him from rats. In 1883 she and Tatiana Lebedeva were transferred to the Kara Prison Mines. The journey north, which was on foot, lasted two years, was hardly better than life in Trubetskov Dungeon. As it was clear that her baby would not survive the long journey, Yakimova gave it away to "some well-wishers who had come out to greet the prisoners with messages of support and tears of sympathy"

George Kennan attempted to obtain sponsorship for and on-the-spot study of Siberia and the exile system. After approaching several organizations he eventually persuaded Century Magazine to finance the expedition. After a preliminary visit to St. Petersburg and Moscow to perfect the arrangements, Kennan set off on his journey in the early spring of 1885, accompanied by the artist, George Albert Frost. "We both spoke Russian, both had been in Siberia before, and I was making to the empire my fourth journey."

Kennan interviewed several political prisoners. This included Anna Korba a member of the People's Will. "In 1877 the Russo-Turkish War broke out, and opened to her ardent and generous nature a new field of benevolent activity. As soon as wounded Russian soldiers began to come back from Bulgaria, she went into the hospitals of Minsk as a Sister of Mercy, and a short time afterward put on the uniform of the International Association of the Red Cross, and went to the front and took a position as a Red Cross nurse in a Russian field-hospital beyond the Danube. She was then hardly twenty-seven years of age. What she saw and what she suffered in the course of that terrible Russo-Turkish campaign can be imagined by those who have seen the paintings of the Russian artist Vereshchagin. Her experience had a marked and permanent effect upon her character. She became an enthusiastic lover and admirer of the common Russian peasant, who bears upon his weary shoulders the whole burden of the Russian state, but who is cheated, robbed, and oppressed, even while fighting the battles of his country. She determined to devote the remainder of her life to the education and the emancipation of this oppressed class of the Russian people. At the close of the war she returned to Russia, but was almost immediately prostrated by typhus fever contracted in an overcrowded hospital. After a long and dangerous illness she finally recovered, and began the task that she had set herself; but she was opposed and thwarted at every step by the police and the bureaucratic officials who were interested in maintaining the existing state of things, and she gradually became convinced that before much could be done to improve the condition of the common people the Government must be overthrown. She... participated actively in all the attempts that were made between 1879 and 1882 to overthrow the autocracy and establish a constitutional form of government." She was arrested and found guilty of carrying out propaganda activities and was sent to the Kara Prison Mines in Siberia.

George Kennan carried out a long interview with Prince Alexander Kropotkin, the brother of Prince Peter Kropotkin. Kennan pointed out that: "Prince Alexander Kropotkin's... views with regard to social and political questions would have been regarded in America, or even in western Europe, as very moderate, and he had never taken any part in Russian revolutionary agitation. He was, however, a man of impetuous temperament, high standard of honor, and great frankness and directness of speech; and these characteristics were perhaps enough to attract to him the suspicious attention of the Russian police." Kropotkin told Kennan: "I am not a nihilist nor a revolutionist and I never have been. I was exiled simply because I dared to think, and to say - what I thought, about the things that happened around me, and because I was the brother of a man whom the Russian Government hated." His first arrest was as a result of having a copy of a book, Self-Reliance, by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Kennan had great respect for Kropotkin and was distressed when he heard about how he committed suicide while in exile in 1890.

A large percentage of the political prisoners tried to escape from the prison camps. Leon Trotsky was imprisoned in a camp close to the Lena River. "The Lena was the great water route of the exiled. Those who had completed their terms returned to the south by way of the river. But communication was continuous between these various nests of the banished which kept growing with the rise of the revolutionary tide. The exiles exchanged letters with each other. The exiles were no longer willing to stay in their places of confinement, and there was an epidemic of escapes. We had to arrange a system of rotation. In almost every village there were individual peasants who as youths had come under the influence of the older revolutionaries. They would carry the 'politicals' away secretly in boats, in carts or in sledges, and pass them along from one to another. The police in Siberia were as helpless as we were. The vastness of the country was an ally, but an enemy as well. It was very hard to catch a runaway, but the chances were that he would be drowned in the river or frozen to death in the primeval forests."

Most of the revolutionary leaders in Russia spent time in Siberia. This included Catherine Breshkovskaya, Lev Deich, Olga Liubatovich, Vera Figner, Gregory Gershuni, Praskovia Ivanovskia, Peter Stuchka, Mark Natanson, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Sophia Smidovich, Inessa Armand, Andrey Bubnov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Mikhail Frunze, Adolf Joffe, Maihail Tomsky, Ivan Smirnov, Yakov Sverdlov, Irakli Tsereteli, Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Vsevolod Volin and Anatoli Lunacharsky.

After the Russian Revolution the labour camps in Siberia were closed down. These were later reopened by Joseph Stalin and opponents of his regime were sent to what became known as Glavnoye Upravleniye Lagere (Gulag). It is estimated that around 50 million perished in Soviet gulags during this period.

Primary Sources

(1) George Kennan, Siberia and the Exile System (1891)

Russian exiles began to go to Siberia very soon after its discovery and conquest-as early probably as the first half of the seventeenth century. The earliest mention of exile in Russian legislation is in a law of the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1648. Exile, however, at that time, was regarded not as a punishment in itself, but as a means of getting criminals who had already been punished out of the way. The Russian criminal code of that age was almost incredibly cruel and barbarous. Men were impaled on sharp stakes, hanged, and beheaded by the hundred for crimes that would not now be regarded as capital in any civilized country in the world; while lesser offenders were flogged with the knut and bastinado, branded with hot irons, mutilated by amputation of one or more of their limbs, deprived of their tongues, and suspended in the air by hooks passed under two of their ribs until they died a lingering and miserable death.

When criminals had been thus knuted, bastinadoed, branded, or crippled by amputation, Siberian exile was resorted to as a quick and easy method of getting them out of the way; and in this attempt to rid society of criminals who were both morally and physically useless Siberian exile had its origin. The amelioration, however, of the Russian criminal code, which began in the latter part of the seventeenth century, and the progressive development of Siberia itself gradually brought about a change in the view taken of Siberian exile. Instead of regarding it, as before, as a means of getting rid of disabled criminals, the Government began to look upon it as a means of populating and developing a new and promising part of its Asiatic territory. Toward the close of the seventeenth century, therefore, we find a number of ukazes abolishing personal mutilation as a method of punishment, and substituting for it, and in a large number of cases even for the death penalty, the banishment of the criminal to Siberia with all his family. About the same time exile, as a punishment, began to be extended to a large number of crimes that had previously been punished in other ways; as, for example, desertion from the army, assault with intent to kill, and vagrancy when the vagrant was unfit for military service and no land owner or village commune would take charge of him. Men were exiled, too, for almost every conceivable sort of minor offense, such, for instance, as fortune-telling, prize-fighting, snuff-taking, driving with reins, begging with a pretense of being in distress, and setting fire to property accidentally.

In the eighteenth century the great mineral and agricultural resources of Siberia began to attract to it the serious and earnest attention of the Russian government. The discovery of the Daurski silver mines, and the rich mines of Nerchinsk in the Siberian territory of the Trans-Baikal, created a sudden demand for labor, which led the government to promulgate a new series of ukazes providing for the transportation thither of convicts from the Russian prisons. In 1762 permission was given to all individuals and corporations owning serfs, to hand the latter over to the local authorities for banishment to Siberia whenever they thought they had good reason for so doing. With the abolition of capital punishment in 1753, all criminals that, under the old law, would have been put to death, were condemned to perpetual exile in Siberia with hard labor.

(2) Major-General Nicolai Baranof, the Governor of Archangel, report sent to the Minister of the Interior (1886)

From the experience of previous years, and from my own personal observation, I have come to the conclusion that administrative exile for political reasons is much more likely to spoil the character of a man than to reform it. The transition from a life of comfort to a life of poverty, from a social life to a life in which there is no society whatever, and from a life of activity to a life of compulsory inaction, produces such ruinous consequences, that, not infrequently, especially of late, we find the political exiles going insane, attempting to commit suicide, and even committing suicide. All this is the direct result of the abnormal conditions under which exile compels an intellectually cultivated person to live. There has not vet been a single case where a man, suspected with good reason of political untrustworthiness and exiled by administrative process, has returned from such banishment reconciled to the Government, convinced of his error, and changed into a useful member of society and a faithful servant of the Throne. On the other hand, it often happens that a man who has been exiled ill consequence of a misunderstanding, or an administrative mistake, becomes politically untrustworthy for the first time in the place to which he has been banished - partly by reason of his association there with real enemies of the Government, and partly as a result of personal exasperation. Furthermore, if a man is infected with anti-Government ideas, all the circumstances of exile tend only to increase the infection, to sharpen his faculties, and to change him from a theoretical to a practical - that is, an extremely dangerous-man. If, on the contrary, he has not been guilty of taking part in a revolutionary movement, exile, by force of the same circumstances, develops in his mind the idea of revolution, or, in other words, produces a result directly opposite to that which it was intended to produce. No matter how exile by administrative process may be regulated and restricted, it will always suggest to the mind of the exiled person the idea of uncontrolled official license, and this alone is sufficient to prevent any reformation whatever.

(3) Praskovia Ivanovskia spent fifteen years in prison. During this time she smuggled out a letter to a friend about the problems of being in prison in Siberia.

The Kara prison most resembles a tumbledown stable. The dampness and cold are ferocious; there's no heat at all in the cells, only two stoves in the corridor. The cell doors are kept open day and night - otherwise we would freeze to death. In winter, a thick layer of ice forms on the walls of the corner cells and at night, the undersides of the straw mattresses get covered with hoarfrost.

Everyone congregates in the corridor in winter, because it's closer to the stoves and you get a warm draft. Since the cells farthest from the stove are completely uninhabitable, the people who live in them carry their beds into the corridor.

I've been one of the temporary residents of the corridor, and I can say that the accommodations weren't particularly comfortable or quiet. Cooking, bread baking, and all sorts of washing were done there: at the table, someone would be reading periodicals, while right next to her, there would be someone making chopped meat for the sick people or sloshing underwear around in a trough.

Last winter, however, we drew up a constitution for ourselves. Since the cold made it impossible to do any studying in the cells, and since the bustle in the corridor would be used exclusively for reading. Anyone who wanted to strike up a conversation had to move off into one of the distant cells and speak softly, since the partitions were thin and loud talk could be heard everywhere.

(4) Cathy Porter, Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976)

Those sentenced in the Trial of the 20 were sent to the Trubetskoy Dungeon, one of the most horrible of Russian prisons. Few survived the ordeal; torture and rape were everyday occurrences in the dungeons, through whose soundproofed walls little information reached the outside world. It was here that Anna Yakimova had her baby, watching over him night and day to protect him from rats, trying to warm him with her breath and watching him slowly die as she ran out of milk. After a year in Trubetskoy, during which most of the prisoners had died or committed suicide, she and Tatiana Lebedeva were transferred to the Kara prison mines. The journey north, which lasted two years, was scarcely more endurable than life in the dungeons. Anna Yakimova abandoned all hope for her baby, and under such conditions it was hardly surprising that she eventually gave him over to some well-wishers who had come out to greet the prisoners with messages of support and tears of sympathy.

(5) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930)

We were going down the river Lena, a few barges of convicts, with a convoy of soldiers, drifting slowly along with the current. It was cold at night, and the heavy coats with which we covered ourselves were thick with frost in the morning. All along the way, at villages decided on beforehand, one or two convicts were put ashore. As well as I can remember it took about three weeks before we came to the village of Ust-Kut. There I was put ashore with one of the women prisoners a close associate of mine from Nikolayev. Alexandra Lvovna had one of the important positions in the South Russian Workers' Union. The work that were doing bound us closely together, and so, to avoid being separated, we had been married in the transfer prison in Moscow.

The village comprised about a hundred peasant huts. We settled down in one of them, on the very edge of the village. About us were the woods; below us, the river. Farther north, down the Lena, there were gold-mines. The reflection of the gold seemed to hover about the river.

In the summer our lives were made wretched by midges. They even bit to death a cow which had lost its way in the woods. The peasants wore nets of tarred horsehair over their heads. In the spring and autumn the village was buried in mud. To be sure, the country was beautiful, but during these years it left me cold. I hated to waste interest and time on it. I lived between the woods and the river, and I hardly noticed them - I was so busy with my books and personal relations. I was studying Marx, brushing the cockroaches off the page.

The Lena was the great water route of the exiled. Those who had completed their terms returned to the south by way of the river. But communication was continuous between these various nests of the banished which kept growing with the rise of the revolutionary tide. The exiles exchanged letters with each other.

The exiles were no longer willing to stay in their places of confinement, and there was an epidemic of escapes. We had to arrange a system of rotation. In almost every village there were individual peasants who as youths had come under the influence of the older revolutionaries. They would carry the 'politicals' away secretly in boats, in carts or in sledges, and pass them along from one to another. The police in Siberia were as helpless as we were. The vastness of the country was an ally, but an enemy as well. It was very hard to catch a runaway, but the chances were that he would be drowned in the river or frozen to death in the primeval forests.

(6) Victor Serge worked with Vera Figner in 1929 when he had the task of translating her memoirs into French. Serge revealed in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, that in her final years Figner came close to being arrested by the Soviet Secret Police.

I was translating her memoirs, and she overwhelmed me with corrections framed in her fastidious tones. She was, at 77 years of age, a tiny old woman, wrapped in a shawl against the cold, her features still regular and preserving the impression of a classical beauty, a perfect intellectual clarity and a flawless nobility of soul. Doubtless she looked upon herself proudly as the living symbol of the revolutionary generations of the past, generations of purity and sacrifice.

As a member of the Central Committee of the Narodnaya Volya (People's Will Party) from 1879 to 1883, Vera Figner was responsible, together with her comrades, for the decision to take to terrorism as a last resort; she took part in organizing ten or so attempts against Tsar Alexander II, arranged the last and successful attack on 1st March 1881, and kept the Party's activity going for nearly two years after the arrest and hanging of the other leaders.

After this this she spent twenty years in the prison-fortress of Schlusselburg, and six years in Siberia. From all these struggles she emerged frail, hard and upright, as exacting towards herself as she was to others. In 1931, her great age and quite exceptional moral standing saved her from imprisonment, although she did not conceal her outbursts of rebellion. She died at liberty, though under surveillance, in 1942.

(7) Eugene Lyons, Workers’ Paradise Lost: Fifty Years of Soviet Communism: A Balance Sheet (1967)

The decade of 1906-1916 was sufficiently blood-soaked for its time. Andrei Vishinsky, long Stalin's chief administrator of Soviet "justice," was not likely to underestimate anything in favor of the old regime. Yet according to his own figures there were in 1913 only 32,000 convicts at hard labor (hatorga) in Russia, including ordinary criminals. They could all have been accommodated in one of the larger Soviet forced-labor camps; and this was at the peak of the reaction that followed the 1905 revolution. About 25,000 were sentenced to Siberia and other exile regions in the first ten years of the century and 27,000 more between 1911 and 1916...

In the 1880's, George Kennan (great-uncle of his namesake, the former American ambassador to Moscow) made his historic investigation of the Siberian exile system, and published his findings in two fat volumes. Not only was he permitted to visit any prisons and exile places he chose but St. Petersburg gave him full cooperation. He returned to the United States to condemn what he had seen with unflagging passion. Yet he acknowledged that "the number of political offenders is much smaller than it is generally supposed to be." He estimated the yearly score of political exile, between 1879 and 1884, at 150. The totals increased rapidly after the turn of the century and in particular after 1905.

The most extreme estimates came from Prince Peter Kropotkin, the anarchist philosopher, in his efforts to awaken the conscience of mankind. Writing in London in 1909, he gave the number of all inmates in Russian prisons as 181,000 and the number of exiles as 74,000 plus some 30,000 more then believed to be in process of transportation. The totals covered offenders of all categories, with ordinary prisoners constituting a majority of convicts and "politicals" a majority of exiles...

The exiles were usually joined by their families and lived a relatively normal life despite harsh surroundings. They were in unlimited correspondence with friends and political comrades in Russia and abroad. Those who had money or received help from outside - committees to aid Russian political prisoners collected funds throughout the liberal world - often went in for hunting, fishing, and other sports. Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin were all ardent huntsmen in their exile years.

Reading today the memoirs of exiles during the monarchy is an interesting experience, against the knowledge of Soviet concentration-camp purgatories. Nadezhda Krupskava, Lenin's wife, recounting their routine in Siberia, might be talking of a middle-class winter vacation. One of her letters to a relative does have a tragic note: the maid has just walked out on her, Mrs. Lenin reports, and she has been obliged to do her own housework!