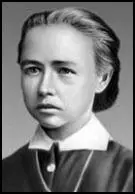

Sophia Perovskaya

Sophia Perovskaya, the daughter of Lev Perovsky, governor-general of St. Petersburg, was born on 13th September, 1853. His wife and four children occupied a mansion in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Sophia's grandfather had been governor of the Crimea in the reign of Tsar Alexander I.

Perovskaya did not get on well with her authoritarian father and spent much of her early life on her mother's estate in the Crimea. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has argued: "Lev Perovsky was an arrogant, capricious man, and his presence at home provoked constant scenes. He spent most of his time drinking and playing cards with his friends. He felt that his wife Varvara had betrayed him by not being able to modify her simple provincial ways so as to scintillate at her husband's side at social gatherings. She was a sensitive, deeply religious woman, passionately involved with her children. She was especially concerned not to inflict on Sophia and her sister Marya the stupefying classes in French and deportment that had passed for education in her day. Sophia was a reserved child, deeply attached to her mother and outraged by her father's offensive criticisms of his wife; these criticisms inevitably extended to her too, sometimes in the form of offensive banter, sometimes as outright abuse."

In 1869 Perovskaya enrolled in the Alarchin Women's College in St. Petersburg. She joined the women's circle and became friends with Anna Korba and others who had developed revolutionary ideas. Eventually she joined the secret society, Land and Liberty. The group, led by Mark Natanson, demanded that the Russian Empire should be dissolved. It also believed that two thirds of the land should be transferred to the peasants where it would be organized in self-governing communes. It remained a small group and at its peak only had around 200 members.

Elizabeth Kovalskaia met Sophia during this period: "She was short and strongly built, with close-cropped hair, and she wore an outfit that seemed almost to have the become the uniform for the advocates of the woman question: a Russian blouse, cinched with a leather belt, and a short, dark skirt. Her hair was pulled back revealling a large, intelligent forehead, and her large grey eyes, in which one sensed exceptional energy, radiated cheerfulness. In general she looked more like a young boy than a girl."

In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya). Others, such as George Plekhanov formed Black Repartition, a group that rejected terrorism and supported a socialist propaganda campaign among workers and peasants.

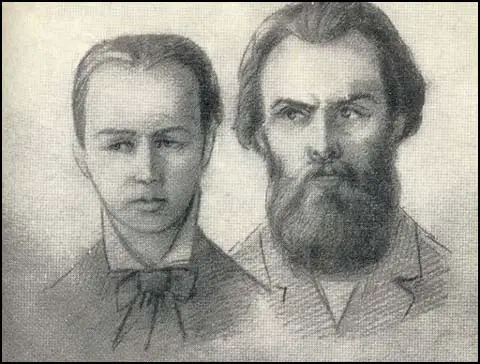

Soon afterwards the People's Will decided to assassinate Alexander II. A directive committee was formed consisting of Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Timofei Mikhailov, Lev Tikhomirov, Mikhail Frolenko, Vera Figner and Anna Yakimova. Zhelyabov was considered the leader of the group. However, Figner considered him to be overbearing and lacking in depth: "He had not suffered enough. For him all was hope and light." Zhelyabov had a magnetic personality and had a reputation for exerting a strong influence over women.

Zhelyabov and Perovskaya attempted to use nitroglycerine to destroy the Tsar train. However, the terrorist miscalculated and it destroyed another train instead. An attempt the blow up the Kamenny Bridge in St. Petersburg as the Tsar was passing over it was also unsuccessful. Figner blamed Zhelyabov for these failures but others in the group felt he had been unlucky rather than incompetent.

During this period Perovskaya fell in love with Zhelyabov. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has argued: "They made no secret of the fact now that they were in love, and though both of them had at one time solemnly denounced any friendships within the Party as a 'violation of social justice', they now found that passion gave new meaning to their work together. They were both in constantly high spirits, working closely together on developing the workers' section of the Party. The realization that terror was only the first stage in the political struggle (even if they only lived to see this first stage) released a new flood of energy in them."

Lev Tikhomirov recalled: "It meant a great deal to him. He valued her intelligence and character, and as a colleague in the cause she was incomparable. Of course one can't talk of happiness. There was constant anxiety - not for themselves but for each other - continual preoccupations, an increasing flood of work which meant that they could scarcely ever be alone, the certainty that sooner or later there was bound to come a tragic ending. And yet there were times, when work was going well, when they were able to forget for a while, and then it was a joy to see them, especially her. Sophia's feelings were so overwhelming that in any but her it would have crowded out all thoughts of her work."

In November 1879 Stefan Khalturin managed to find work as a carpenter in the Winter Palace. According to Adam Bruno Ulam, the author of Prophets and Conspirators in Pre-Revolutionary Russia (1998): "There was, incomprehensible as it seems, no security check of workman employed at the palace. Stephan Khalturin, a joiner, long sought by the police as one of the organizers of the Northern Union of Russian workers, found no difficulty in applying for and getting a job there under a false name. Conditions at the palace, judging from his reports to revolutionary friends, epitomized those of Russia itself: the outward splendor of the emperor's residence concealed utter chaos in its management: people wandered in and out, and imperial servants resplendent in livery were paid as little as fifteen rubles a month and were compelled to resort to pilfering. The working crew were allowed to sleep in a cellar apartment directly under the dining suite."

Khalturin approached George Plekhanov about the possibility of using this opportunity to kill Tsar Alexander II. He rejected the idea but did put him in touch with the People's Will who were committed to a policy of assassination. It was agreed that Khalturin should try and kill the Tsar and each day he brought packets of dynamite, supplied by Anna Yakimova and Nikolai Kibalchich, into his room and concealed it in his bedding. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has argued: "His workmates regarded him as a clown and a simpleton and warned him against socialists, easily identifiable apparently for their wild eyes and provocative gestures. He worked patiently, familiarizing himself with the Tsar's every movement, and by mid-January Yakimova and Kibalchich had provided him with a hundred pounds of dynamite, which he hid under his bed."

On 17th February, 1880, Stefan Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander II would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. On 25th February, 1880, Alexander II announced that he was considering granting the Russian people a constitution. To show his good will a number of political prisoners were released from prison. Mikhail Loris-Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, was given the task of devising a constitution that would satisfy the reformers but at the same time preserve the powers of the autocracy. At the same time the Russian Police Department established a special section that dealt with internal security. This unit eventually became known as the Okhrana. Under the control of Loris-Melikof, undercover agents began joining political organizations that were campaigning for social reform.

In January, 1881, Mikhail Loris-Melikof presented his plans to Alexander II. They included an expansion of the powers of the Zemstvo. Under his plan, each zemstov would also have the power to send delegates to a national assembly called the Gosudarstvenny Soviet that would have the power to initiate legislation. Alexander was concerned that the plan would give too much power to the national assembly and appointed a committee to look at the scheme in more detail.

The People's Will became increasingly angry at the failure of the Russian government to announce details of the new constitution. They therefore began to make plans for another assassination attempt. Those involved in the plot included Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Vera Figner, Anna Yakimova, Grigory Isaev, Gesia Gelfman, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Mikhail Frolenko, Timofei Mikhailov, Tatiana Lebedeva and Alexander Kviatkovsky.

Isaev and Yakimova were commissioned to prepare the bombs that were needed to kill the Tsar. Isaev made some technical error and a bomb went off badly damaging his right hand. Yakimova took him to hospital, where she watched over his bed to prevent him from incriminating himself in his delirium. As soon as he regained consciousness he insisted on leaving, although he was now missing three fingers of his right hand. He was unable to continue working and Yakimova now had sole responsibility for preparing the bombs.

A crisis meeting was held in which Timofei Mikhailov called for work to continue on all fronts. However, Sophia Perovskaya and Anna Yakimova argued that they should concentrate on the plans to assassinate the Tsar. Nikolai Kibalchich was heard to remark: "Have you noticed how much crueller our girls are than our men?" It was eventually agreed that Perovkaya and Yakimova was right. It was decided to form a watching party. These members had the task of noting every movement of the Tsar.

It was discovered that every Sunday the Tsar took a drive along Malaya Sadovaya Street. It was decided that this was a suitable place to attack. Yakimova was given the task of renting a flat in the street. Gesia Gelfman had a flat on Telezhnaya Street and this became the headquarters of the assassins whereas the home of Vera Figner was used as an explosives workshop.

The Okhrana discovered that their was a plot to kill Alexander II. One of their leaders, Andrei Zhelyabov, was arrested on 28th February, 1881, but refused to provide any information on the conspiracy. He confidently told the police that nothing they could do would save the life of the Tsar. Alexander Kviatkovsky, another member of the assassination team, was arrested soon afterwards.

The conspirators decided to make their attack on 1st March, 1881. Sophia Perovskaya was worried that the Tsar would now change his route for his Sunday drive. She therefore gave the orders for bombers to he placed along the Ekaterinsky Canal. Grigory Isaev had laid a mine on Malaya Sadovaya Street and Anna Yakimova was to watch from the window of her flat and when she saw the carriage approaching give the signal to Mikhail Frolenko.

Tsar Alexander II decided to travel along the Ekaterinsky Canal. An armed Cossack sat with the coach-driver and another six Cossacks followed on horseback. Behind them came a group of police officers in sledges. Perovskaya, who was stationed at the intersection between the two routes, gave the signal to Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov to throw their bombs at the Tsar's carriage. The bombs missed the carriage and instead landed amongst the Cossacks. The Tsar was unhurt but insisted on getting out of the carriage to check the condition of the injured men. While he was standing with the wounded Cossacks another terrorist, Ignatei Grinevitski, threw his bomb. Alexander was killed instantly and the explosion was so great that Grinevitski also died from the bomb blast.

The terrorists quickly escaped from the scene and that evening assembled at the flat being rented by Vera Figner. She later recalled: "Everything was peaceful as I walked through the streets. But half an hour after I reached the apartment of some friends, a man appeared with the news that two crashes like cannon shots had rung out, that people were saying the sovereign had been killed, and that the oath was already being administered to the heir. I rushed outside. The streets were in turmoil: people were talking about the sovereign, about wounds, death, blood.... I rushed back to my companions. I was so overwrought that I could barely summon the strength to stammer out that the Tsar had been killed. I was sobbing; the nightmare that had weighed over Russia for so many years had been lifted. This moment was the recompense for all the brutalities and atrocities inflicted on hundreds and thousands of our people.... The dawn of the New Russia was at hand! At that solemn moment all we could think of was the happy future of our country."

The evening after the assassination the Executive Committee of the People's Will sent an open letter announcing it was willing to negotiate with the authorities: "The inevitable alternatives are revolution or a voluntary transfer of power to the people. We turn to you as a citizen and a man of honour, and we demand: (i) amnesty for all political prisoners, (ii) the summoning of a representative assembly of the whole nation". Karl Marx was one of many radicals who sent a message of support after the publication of the letter.

Nikolai Rysakov, one of the bombers was arrested at the scene of the crime. Sophia Perovskaya told her comrades: "I know Rysakov and he will say nothing." However, Rysakov was tortured by the Okhrana and was forced to give information on the other conspirators. The following day the police raided the flat being used by the terrorists. Gesia Gelfman was arrested but Nikolai Sablin committed suicide before he could be taken alive. Soon afterwards, Timofei Mikhailov, walked into the trap and was arrested.

Thousands of Cossacks were sent into St. Petersburg and roadblocks were set up, and all routes out of the city were barred. An arrest warrant was issued for Sophia Perovskaya. Her bodyguard, Tyrkov, claimed that she seemed to have "lost her mind" and refused to try and escape from the city. According to Tyrkov, her main concern was to develop a plan to rescue Andrei Zhelyabov from prison. She became depressed when on the 3rd March, the newspapers reported that Zhelyabov had claimed full responsibility for the assassination and therefore signing his own death warrant.

Perovskaya was arrested while walking along the Nevsky Prospect on 10th March. Later that month Nikolai Kibalchich, Grigory Isaev and Mikhail Frolenko were also arrested. However, other members of the conspiracy, including Vera Figner and Anna Yakimova, managed to escape from the city. Perovskaya was interrogated by Vyacheslav Plehve, the Director of the Police Department. She admitted her involvement in the assassination but refused to name any of her fellow conspirators.

The trial of Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Rysakov, Helfman and Mikhailov, opened on 25th March, 1881. Prosecutor Muraviev read his immensely long speech that included the passage: "Cast out by men, accursed of their country, may they answer for their crimes before Almighty God! But peace and calm will be restored. Russia, humbling herself before the Will of that Providence which has led her through so sore a burning faith in her glorious future."

Prosecutor Muraviev concentrated his attack on Sophia Perovskaya: "We can imagine a political conspiracy; we can imagine that this conspiracy uses the most cruel, amazing means; we can imagine that a woman should be part of this conspiracy. But that a woman should lead a conspiracy, that she should take on herself all the details of the murder, that she should with cynical coldness place the bomb-throwers, draw a plan and show them where to stand; that a woman should have become the life and soul of this conspiracy, should stand a few steps away from the place of the crime and admire the work of her own hands - any normal feelings of morality can have no understanding of such a role for women." Perovskaya replied: "I do not deny the charges, but I and my friends are accused of brutality, immorality and contempt for public opinion. I wish to say that anyone who knows our lives and the circumstances in which we have had to work would not accuse us of either immorality or brutality."

Karl Marx followed the trial with great interest. He wrote to his daughter, Jenny Longuet: "Have you been following the trial of the assassins in St. Petersburg? They are sterling people through and through.... simple, businesslike, heroic. Shouting and doing are irreconcilable opposites... they try to teach Europe that their modus operandi is a specifically Russian and historically inevitable method about which there is no more reason to moralize - for or against - then there is about the earthquake in Chios."

Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman and Timofei Mikhailov were all sentenced to death. Gelfman announced she was four months pregnant and it was decided to postpone her execution. Perovskaya, as a member of the high nobility, she could appeal against her sentence, however, she refused to do this. It was claimed that Rysakov had gone insane during interrogation. Kibalchich also showed signs that he was mentally unbalanced and talked constantly about a flying machine he had invented.

On 3rd April 1881, Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Rysakov and Mikhailov were given tea and handed their black execution clothes. A placard was hung round their necks with the word "Tsaricide" on it. Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976), has pointed out: "Then the party set off. It was headed by the police carriage, followed by Zhelyabov and Rysakov. Sophia sat with Kibalchich and Mikhailov in the third tumbril. A pale wintry sun shone as the party moved slowly through the streets, already crowded with onlookers, most of them waving and shouting encouragement. High government officials and those wealthy enough to afford the tickets were sitting near to the scaffold that had been erected on Semenovsky Square. The irreplaceable Frolov, Russia's one and only executioner, fiddled drunkenly with the nooses, and Sophia and Zhelyabov were able to say a few last words to one another. The square was surrounded by twelve thousand troops and muffled drum beats sounded. Sophia and Zhelyabov kissed for the last time, then Mikhailov and Kibalchich kissed Sophia. Kibalchich was led to the gallows and hanged. Then it was Mikhailov's turn. Frolov was by now barely able to see straight and the rope broke three times under Mikhailov's weight." It was now Perovskaya's turn. "It's too tight" she told him as he struggled to tie the noose. She died straight away but Zhelyabov, whose noose had not been tight enough, died in agony.

Primary Sources

(1) Elizabeth Kovalskaia first met Sophia Perovskaya at a party held in the home of Alexandra Kornolova in 1869.

She was short and strongly built, with close-cropped hair, and she wore an outfit that seemed almost to have the become the uniform for the advocates of the woman question: a Russian blouse, cinched with a leather belt, and a short, dark skirt. Her hair was pulled back revealling a large, intelligent forehead, and her large grey eyes, in which one sensed exceptional energy, radiated cheerfulness. In general she looked more like a young boy than a girl.

The group began to disperse long after midnight. Alexandra Kornolova, who lived in the apartment, made me stay. When everyone but the girl in grey had gone, she introduced us: the girl was Sophia Perovskaya. Perovskaya suggested that I join a small circle of women who wanted to study political economy, and I agreed.

(2) Olga Liubatovich wrote about meeting Sophia Perovskaya in her autobiography published in 1906.

I had spent the night at Malinovskaia's apartment. Around noon, a modestly dressed young woman appeared at the door. Her striking face - round and small, but for the large, childlike forehead - stood out sharply against the background of her black dress, trimmed with a broad white turn-down collar. She radiated youth and life.

Perovskaya introduced herself and greeted us in the open, direct fashion of an old friend, although she had never met either of us. We clustered around her: obviously, she was pleasantly excited about something. The rapid walk to our apartment had left her breathless, but she immediately began to tell us the story of her escape at the railroad station in Novgorod - a simple story, but it made me tremble.

(3) Praskovia Ivanovskaia joined the People's Will and often visited the home of Sophia Perovskaya and Andrei Zhelyabov.

In the intervals between printing jobs, we visited Sofhia Perovskaya's apartment. She shared the place with Andrei Zhelyabov, and when we stayed late, we saw him, too. To us, the visits to Perovskaia were like a refreshing shower. Sophia always gave us a warm, friendly welcome; she acted as if we were the ones with stimulating ideas and news to share, rather than the reverse. In her easy and natural way, she painstakingly helped us to make sense of the complicated muddle of everyday life and the vacillations of public opinion. She told us about the party's activities among workers, about various circles and organizations, and about the expansion of the revolutionary movement among previously untouched social groups. Perovskaia spoke calmly, without a trace of sentimentality, but there was no hiding the joy that lit up her face and shone in her crinkled, smiling eyes - it was as if she were taking about a child of hers who had recovered from an illness.

(4) In her memoirs Olga Liubatovich described the reactions of Sophia Perovskaya after the failure to assassinate Alexander II in November, 1879.

A few days after the Moscow explosion, Sophia Perovskaya appeared at one of the party's secret apartments in St. Petersburg. The words began to spill out and she emotionally told us the story of the Moscow attempt. On November 19, it was she who waited in the bushes for the Tsar's train to approach and then gave the signal for the explosion that blew up the tracks. But there had been too little dynamite, she told us; how she regretted that so much had been sent to the operation in the south, instead of concentrating it all in Moscow! There was a catch in her voice as she spoke, and in her face reflected intense suffering; she was shaking, either from a chill produced by her bare wet hands or from a painful feeling of failure and long-suppressed emotion. There was nothing I could do to comfort her.

(5) Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931)

My companion (Alexander Berkman) said he was glad to know that I felt that way. All true revolutionists had discarded marriage and were living in freedom. That served to strengthen their love and helped them in their common task. He told me the story of Sophia Perovskaya and Zhelyabov. They had been lovers, had worked in the same group, and together they elaborated the plan for the execution of Alexander II. After the explosion of the bomb Perovskaya vanished. She was in hiding. She had every chance to escape, and her comrades begged her to do so. But she refused. She insisted that she must take the consequences, that she would share the fate of her comrades and die together with Zhelyabov. "Of course, it was wrong of her to be moved by personal sentiment," Berkman commented; "her love for the Cause should have urged her to live for other activities." Again I found myself disagreeing with him. I thought that it could not be wrong to die with one's beloved in a common act-it was beautiful, it was sublime. He retorted that I was too romantic and sentimental for a revolutionist, that the task before us was hard and we must become hard.