Land and Liberty

In 1869, two Russian writers, Mikhail Bakunin and Sergi Nechayev published the book Catechism of a Revolutionist. It included the famous passage: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it."

The book had a great impact on young Russians and in 1876 a secret society, Land and Liberty, was formed. The group, led by Mark Natanson, demanded that the Russian Empire should be dissolved. It also believed that two thirds of the land should be transferred to the peasants where it would be organized in self-governing communes. It remained a small group and at its peak only had around 200 members.

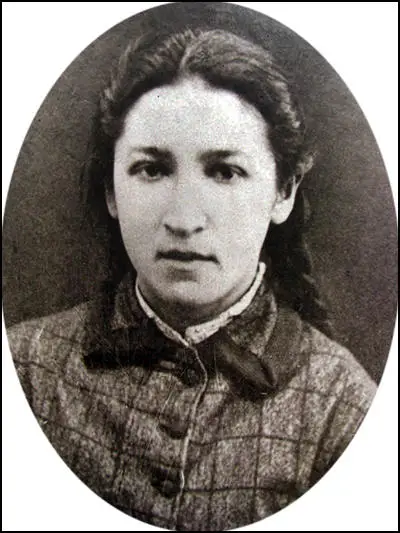

Undercover agents employed by Okhrana soon infiltrated the organization and members began to be arrested and imprisoned. In 1878 Vera Zasulich, a member of Land and Liberty, heard that one of her fellow comrades, Alexei Bogoliubov, had been badly beaten in prison, she decided to seek revenge. Zasulich went to the local prison and shot General Trepov, the police chief of St. Petersburg.

Zasulich was arrested and charged with attempted murder. During the trial the defence produced evidence of such abuses by the police, and Zasulich conducted herself with such dignity, that the jury acquitted her. When the police tried to re-arrest her outside the court, the crowd intervened and allowed her to escape.

Most of the group shared Bakunin's anarchist views and demanded that Russia's land should be handed over to the peasants and the State should be destroyed. The historian, Adam Bruno Ulam, has argued: "This Party, which commemorated in its name the revolutionary grouping of the early sixties, was soon split up by quarrels about its attitude toward terror. The professed aim, the continued agitation among the peasants, grew more and more fruitless."

In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya). Others, such as George Plekhanov formed Black Repartition, a group that rejected terrorism and supported a socialist propaganda campaign among workers and peasants. Elizabeth Kovalskaia was one of those who rejected the ideas of the People's Will: "Firmly convinced that only the people themselves could carry out a socialist revolution and that terror directed at the centre of the state (such as the People's Will advocated) would bring - at best - only a wishy-washy constitution which would in turn strengthen the Russian bourgeoisie, I joined Black Repartition, which had retained the old Land and Liberty program."

Primary Sources

(1) Mikhail Bakunin and Sergi Nechayev, Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869)

The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it.

He despises public opinion. He hates and despises the social morality of his time, its motives and manifestations. Everything which promotes the success of the revolution is moral, everything which hinders it is immoral. The nature of the true revolutionist excludes all romanticism, all tenderness, all ecstasy, all love.

(2) In her memoirs Vera Figner explained how her political views developed while she was living in Geneva.

Our circle in Zurich had arrived at the conviction that it was necessary to assume a position identical to that of people in order to earn their trust and conduct propaganda among them successfully. You had to "take to plain living" - to engage in physical labour, to drink, eat, and dress as the people did, renouncing all the habits and needs of the cultural classes. This was the only way to become close to the people and to get a response to propaganda; furthermore, only manual labour was pure and holy, only by surrendering yourself to it completely could you avoid being an exploiter.

(3) In 1876 Vera Zasulich attempted to kill the police chief, General Trepov after he had given the order to beat fellow revolutionary, Alexei Bogoliubov.

Now Trepov and his entourage were looking at me, their hands occupied by papers and things, and I decided to do it earlier than I had planned - to do it when Trepov stopped opposite my neighbour, before reaching me.

And suddenly there was no neighbour ahead of me - I was first.

"What do you want?"

"A certificate of conduct."

He jotted down something with a pencil and turned to my neighbour.

The revolver was in my hand. I pressed the trigger - a misfire.

My heart missed a beat. Again I pressed. A shot, cries. Now they'll start beating me. This was next in the sequence of events I had thought through so many times.

I threw down the revolver - this also had been decided beforehand; otherwise, in the scuffle, it might go off by itself. I stood and waited.

Suddenly everybody around me began moving, the petitioners scattered, police officers threw themselves at me, and I was seized from both sides.

(4) Olga Liubatovich was in Geneva with Vera Zasulich when news arrived that Alexander Soloviev had attempted to kill Alexander II.

In the spring of 1879, the unexpected news of Alexander Soloviev's attempt on the life of the Tsar threw Geneva's Russian colony into turmoil. Vera Zasulich hid away for three days in deep depression: Soloviev's deed obviously reflected a trend toward direct, active struggle against the government, a trend of which Zasulich disapproved. It seemed to me that her nerves were so strongly affected by violent actions like Soloviev's because she consciously (and perhaps unconsciously, as well) regarded her own deed as the first step in this direction.

Other émigrés were incomparably more tolerant of the attempt: Stefanovich and Deich, for example, merely noted that it might hinder political work among the people. Kravchinskii rejected even this objection. All of us knew from our personal experience, he argued, that extensive work among the people has long been impossible, nor could we expect to expand our activity and attract masses of the people to the socialist cause until we obtained at least a minimum of political freedom, freedom of speech, and the freedom to organize unions.

(5) When the Land and Liberty movement split in October, 1879, Olga Liubatovich joined the People's Will group.

Stefanovich became the head of the Black Repartition, and his friends Vera Zasulich and Lev Deich joined him. But even ardent populists like Vera Figner, who had been working in one of the countryfolk settlements in the provinces, and Sophia Perovskaia joined the People's Will, the group that had taken up arms to defend the people and their apostles.

Black Repartition was stillborn; it left no visible traces of its work among the people at the end of 1879 and the beginning of 1880, because no such activity was possible on a broad scale. After a series of failures, Stefanovich, Deich, Plekhanov, and Zasulich returned abroad.

As for me, naturally I joined the People's Will. The Executive Committee of the People's Will soon began to chart its own course. Its initial plan had been to carry out a number of actions against the governor-generals, but this decision was called into question at one open-air meeting in Lesnoi: shouldn't we concentrate all our forces against the Tsar instead, it was asked. We resolved that this should indeed be the goal of the Executive Committee. The implementation of that decision engaged the People's Will right up to March 1, 1881.

(6) Elizabeth Kovalskaia was a member of Land and Liberty and later joined the Black Repartition faction.

In the spring of 1879, after Governor Krapotkin was assassinated, there was a wave of searches and arrests in Kharkov. I had to flee and go understanding for good. I spent brief periods of time in various cities, reaching St. Petersburg in the fall of that year. By this time, Land and Liberty had split into the People's Will and Black Repartition. Firmly convinced that only the people themselves could carry out a socialist revolution and that terror directed at the centre of the state (such as the People's Will advocated) would bring - at best - only a wishy-washy constitution which would in turn strengthen the Russian bourgeoisie, I joined Black Repartition, which had retained the old Land and Liberty program.

Joining Black Repartition had involved accepting the basic principles of the Land and Liberty program. Those principles had, in fact, guided my own political work previously; my reservations about joining the organization concerned tactics. The experiences of the revolutionaries who had worked in the countryside had not been very successful. From my various approaches to the masses, I had gradually come to the conclusion that two activities should be paramount. The first was economic terror. Now, the program of Black Repartition included this, but the party's emphasis was on local popular uprisings. In my opinion, economic terror was more readily understood by the masses; it defended their interests directly, involved the fewest sacrifices, and stimulated the development of revolutionary spirit. The other major task was organizing workers' union, the members of which would rapidly spread revolutionary activity from the cities to the native villages; and there, too, economic terror should be the heart of the struggle.progra

I recall a very stormy meeting about the printing press which Black Repartition held in one of its conspiratorial apartments. Maria Krylova, who had been serving as the proprietress of Land and Liberty's printing operation, emphatically refused to let the People's Will have the press - she was even prepared to use arms against them, if they took any aggressive actions to get it. George Plekhanov was also strongly opposed to giving up the press, but at the same time, in his characteristic manner, he wittily and venomously ridiculed Krylova's plan for "armed resistance".

(7) David Shub was a member of the Social Democratic Labour Party and was a loyal supporter of George Plekhanov.

A split occurred in the Land and Freedom group in 1879, when an executive committee was set up to organize terrorist acts. A small faction, headed by George Plekhanov, rejected the policy of terrorism and became known as the Black Repartition.

The larger group called itself the People's Will. Both believed that the Russian peasant was by nature strongly inclined to Socialism. Contrary to the Marxist notion that only the industrial working class could bring Socialism, they believed that in Russia the peasant could play the same role as the industrial proletariat in other countries. But the People's Will believed that Socialism could not be realized for some time; the immediate goal was the expropriation of the estates in favour of the peasantry and the establishment of civil liberty.

On Sunday 13th March 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by members of the People's Will.